History

Ashanti Empire

The Ashanti Empire was a powerful West African state known for its wealth, military prowess, and sophisticated political system. It emerged in the 17th century and was centered in present-day Ghana. The empire's economy was based on gold mining and trade, and it played a significant role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Ashanti Empire"

- eBook - ePub

- Daryll Forde, P. M. Kaberry(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In the south Ashanti dominated the Guinea Coast at least from Cape Lahu (Ivory Coast) in the west to Little Popo (Togo) in the east (Dupuis, 1824: xli; M’Leod, 1820: 140). On a conservative estimate, Ashanti had established its ascendancy over an area of some 125,000–150,000 square miles, from the southern coasts through the high forest, heartland of the empire, and far into the northern savannahs. Within this area there lived probably between three and five million people. 6 Economically the territory was rich in exploitable natural resources, especially of gold and kola. Along ancient trade-routes to Hausaland in the north-east, and to Timbuktu and Jenne in the north-west, Ashanti commodities could pass into the entrepôts of the Western Sudan and some, by the trans-Saharan caravan trails, on to the greater markets of North Africa. On the southern shores of Ashanti the agents of Danish, Dutch, English, and French companies had established their numerous factories, and vied with each other, and with the northern merchants, for the trade of the interior. Through the ramifications of the distributive trade, the Ashanti economy became linked with those of Europe and North Africa, responsive to the changing patterns of supply and demand in world markets. The size and complexity of the Ashanti Empire in its developed state posed problems of organization of a quite different order from those that had faced the early kings - eBook - ePub

Kinship and the Social Order.

The Legacy of Lewis Henry Morgan

- Meyer Fortes(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

11Though they lacked the art of writing,12 the Ashanti achieved a sophisticated level of statecraft.13 They had a complex machinery of government and administration based on the king’s capital and linked to a nationwide system of judicial institutions that culminated in the sovereign authority of the king. A hierarchy of palace officials whose appointment was firmly controlled by the king conducted the fiscal affairs and the foreign commerce of the Kumasi chiefdom and thus, indirectly, of the nation, and supervised the intricate organization of the court and capital. Other high-ranking offices were connected with the military organization of the state, the maintenance of communication with the regional chiefdoms, and the implementation of the king’s authority and prerogatives throughout the realm. These offices of the king’s chiefdom, augmented when major issues of policy and war came up by the chiefs and councillors of the associated chiefdoms to form a national assembly, constituted the advisory and judicial councils without whose concurrence the king could not legitimately act in national affairs.To diversification by rank, wealth, occupation, and locality was added the very important differentiation of status between the freeborn citizens and the subjects who were themselves, or were descended from, war captives, refugees, and others of slave or alien status. So powerful, however, was the ideology of common civic status that the incorporation of these alien elements into the descent groups of the freeborn was regarded as a binding moral as well as legal duty.14 - eBook - PDF

Conflict in Africa

Concepts and Realities

- Adda Bruemmer Bozeman(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

403. 48 Spannaus, Zuege aus der Politisehen Organisation Afrikaniseher Voelker und Staaten, pp. 39ff.; also Vansina, Kingdoms of the Savanna, on mystical pow- ers imputed to rulers and other officials. 49 R. S. Rattray, Ashanti (Oxford, 1923), p. 288; also p. 224; Rattray, Ashanti Law and Constitution (London, 1929, repr. 1956), ch. 24. See also W. W. Claridge, A History of the Gold Coast and Ashanti, 2 vols. (London, 1915), and Ward, A History of the Gold Coast. On the origins, historical and legendary, of the Akan of Ghana, consult Eva R. Meyerowitz, The Divine Kingship in Ghana and Ancient Egypt (London, 1960), p. 55, to the effect that the cult of the divine king and the principles of social organization derive largely from ancient Egypt. See also three previous works by the same author on this subject, and William Tordoff, "The Ashanti Confederacy," Journal of African History, 3, No. 3 (1962), 414, on the effectiveness of the administrative system, pp. 415ff. on the su- premacy of the sacred stool over its occupant, and on such reasons for destool- ment as repeatedly rejecting the advice of his elders, breaking a taboo, or acting with excessive cruelty. AFRICA: SHARED REALITIES to say, especially in the context of Occidental historiography, in which the force of magic is not recognized. It is clear from the records, how- ever, that Anotchi—not unlike his Muslim Fulani counterparts 50 —spent years travelling through the land and many months negotiating patiently with each individual chief in order to arouse a desire for concerted ac- tion. 51 Only after these preparations did he counsel Osai Tutu that the moment for union had come, and this event was then sealed by appropri- ate ceremonies and magical activities. - eBook - ePub

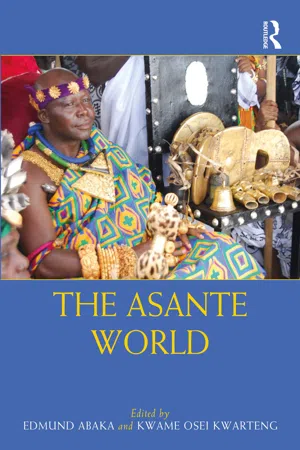

- Edmund Abaka, Kwame Osei Kwarteng, Edmund Abaka, Kwame Osei Kwarteng(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

A History of the Gold Coast and Ashanti , p. 210.21 Osei, An Outline of Asante History , pp. 15–18.22 Graham W. Irwin, “Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante”, The International Journal of African Historical Studies , 8(1), 1975, p. 90.23 Thomas E. Bowdich, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee , (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 92.24 Tieku, Tete Wɔ Bi KyerƐ , p. 231.25 Osei, An Outline of Asante History , p. 19; Tieku, Tete Wɔ Bi KyerƐ , p. 234.26 Ivor Wilks, “Aspects of Bureaucratization in Ashanti in the Nineteenth Century”, The Journal of African History , 7(2), 1966, p. 216.27 Aidoo, “Order and Conflict in the Asante Empire”, p. 10.28 W. E. Ward, Short History of Ghana , (London: Longman and Green Co., 1957), p. 45.29 Larry W. Yarak, “Elmina and Greater Asante in the Nineteenth Century”, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute , 56(1), 1986, p. 36.30 Wilks, Asante in the 19th Century , p. 48.31 Rattray also shares this view, as he likens it to the European feudal system. Aidoo, “Order and Conflict in the Asante Empire”, p. 11; R. S. Rattray, Ashanti Law and Constitution , (London: Oxford University, Press, 1929), p. 77.32 The appeatuo was the war tax paid based on the expenditure on arms and ammunition; it was shared among the units of the kingdom, the divisions, sub-divisions, village, and lineages. The heads of the units were responsible for collecting it from every male and female above the age of 18. Kwame Arhin, “The Financing of the Ashanti Expansion (1700–1820)”, Journal of the International African Institute , 37(3), 1967, p. 284.33 Aidoo, “Order and Conflict in the Asante Empire”, p. 12.34 William Tordoff, “The Ashanti Confederacy”, The Journal of African History , 3(3), 1962, p. 405.35 Arhin, “The Structure of Greater Ashanti (1700–1824)”, p. 76.36 Ibid.37 Yarak, “Elmina and Greater Asante in the Nineteenth Century”, p. 36.38 Arhin, “The Structure of Greater Ashanti (1700–1824)”, p. 65.39 W. E. Ward, A Short History of the Gold Coast - eBook - PDF

Myths, State Expansion, and the Birth of Globalization

A Comparative Perspective

- J. Carlson(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

By the early 1700s Asante solidified and expanded control over the interior of the Gold Coast. This gave the Asante control of the gold, slave, and ivory resources of the area, which proved a double motivation for greater expansion. On one hand, the Asante Kingdom was able to extract greater surplus from its tributary states, which could then be used to sup- port territorial expansion. This was supplemented by spoils from the cam- paigns of suppression the growing empire was forced to carry out, as Asante traders were habitually molested on various routes to coastal markets. This led to war with Akyem in 1717, in which Osei Tutu was reportedly killed. The Asante continued their expansion under Asantehene Opoku Ware, and the first half of the eighteenth century was largely a period of war: [B]y 1730 the Doma states of Abamperedase, Suman and Gyaman, were in the hands of Asante. Under Osei Tutu’s successor, Opoku Ware, the Bono Kingdom was destroyed and incorporated into Asante, together with all its tributary states from Banda to Krakye on the Volta. Then Nta (Gonja) and Dagomba in the north were subjugated, as were the three Akyem states in the south-east, and Sehwi in the west. In less than fifty years the Asante reigned supreme over most of the Gold Coast and parts of the French Ivory Coast. (Meyerowitz 1952:111) It was precisely the drastic extent of Asante dominance that led them into conflict with the European powers during the latter half of the eighteenth century. By 1729 the Asante had extended their interior territory and even expanded out to the coast at Cape Apollonia, after waging a war of conquest against the West Africa and the Rise of Asante ● 107 Aowin in 1715. Yet European cartographic sources fail to reflect this changing reality (cf. d’Anville 1729). The Asante are finally represented as a distinct political entity, having entered the European information network, but the extent of Asante rule is unknown. - eBook - PDF

Islam in a Zongo

Muslim Lifeworlds in Asante, Ghana

- Benedikt Pontzen(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

See Yunus Dumbe (2011; 2013), Ousman Kobo (2009; 2012), and Nathan Samwini (2006) for more recent historical developments. 2 Asa nti translates as ‘because of the war’. Asante designates a group of people, a dominion, language, history, ‘culture’, and ‘tradition’. It is as shifting and complex a designation as English, Nuer, or German. Its boundaries are fuzzy; its ‘chiefs’ (ahenfoɔ) are recognised and partially integrated by the state, but they have no territorial sovereignty. ‘Ashanti Region’ refers to a political, territorial, and administrative area in the Ghanaian state with state boundaries, a regional government, and political representatives. Asante partly overlaps with (and partly outreaches) the Ashanti Region, and its coherence is anything but settled. 32 religious conceptions, practices, and imaginaries, including the manu- facture of amulets or funeral prayers, into their emerging community. Hence, Islam in the zongos predates the actual formation of these wards. Furthermore, there never existed such a thing as a ‘zongo Islam’: in these wards, various Islamic groups were struggling for, maintaining, or loosening religious hegemony – that is, intellectual, moral, and cultural leadership (cf. Gramsci 2000 [1988]: 194, 249) in Islamic matters. The once prevalent ‘Suwarian tradition’, which apparently shaped Islam in the region during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Wilks 1968; 2000; 2011; Wilks, Hunwick, and Sey 2003) 3 and has left traces across West Africa (Sanneh 1997: 37, 214; Ware 2014: 87–90), is no longer a major Islamic tradition today. In the late nineteenth century, the Sufi _ tarīqa (path) of the Qadiriyya, an Islamic order with roots in thirteenth- century Baghdad (Robinson 2004: 18–20; Stewart 1976: 90–1; Vikor 2000: 443–9), emerged as an ascendant Sufi order in Asante. - eBook - PDF

Power and State Formation in West Africa

Appolonia from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century

- P. Valsecchi(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

This is even more the case with historiography of Asante, which understandably concentrates on the developments at the center of one of the most complex states and imperial organizations in West Africa. However, other critical elements emerge in the historical study of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which suggest that regional- wide associative networks among groups other than the state continued to be of crucial political relevance, albeit with different intensity and significance according to the specific historical context. The situation that can be uncovered in the eighteenth-century his- tory of the western Akan areas is particularly representative. It is clear in this case how, over a long period of time, it is extremely difficult to isolate developments in different local ruling groups from the wider and more general context, except in the case of studies into very specific events that are restricted both geographically and chrono- logically. Indeed, historical material in the wider sense of the term (European written sources and local “traditions”) always tends to call the researcher’s attention to contexts that clearly transcend the logic of territorial, political, or “ethnic” groupings on a local scale, sug- gesting or even openly asserting the existence of networks of relations with complex ramifications that are extremely difficult to disentangle. Neglect of this fundamental reality risks considerably restricting the academic value of local studies or “ethnic histories.” The particular nature of this situation, which relates to a vast collection of political entities that at least include the current Ahanta, Nzema, Egila (Edwira), Pepesaa, Wassa, Aowin, Sanwi, Ehotile (Mekyibo), Abure (Bonua or Bonoua), and Bassam, has been vividly described by J. P. T. Huydecoper, the Dutch commander of St. Anthony’s Fort in Axim. - eBook - PDF

Africa in the World

Capitalism, Empire, Nation-State

- Frederick Cooper(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

The king of Ghana, reported the traveler and geographer al-Bakri in the late eleventh century, was not a Muslim, but Muslim traders—Berber and Sudanese—constituted a strong community around him and literate Muslims served the court. Islam provided a common moral framework as well as a code of laws that helped to develop the relations of trust that facilitated trade. But Islam did not extinguish the variety of religious prac-tices among the pastoralists and farmers of the region, nor did the kings expect that ordinary people would give up their religious practices or vil-lage communities. Perhaps fifteen to twenty thousand people lived in the capital, and it commanded agricultural resources—from tribute or the labor of royal slaves—from a large surrounding area. The empire form— in a relatively loose variant—suited the conditions well. Ghana consti-tuted a polity of enormous size, and although its power and that of neighboring polities similarly constituted fluctuated, it exhibited impres-sive political continuity, from the late eighth to the early thirteenth century. 4 The importance of Ghana—the pioneer—and the successor empires of the Sahel—Mali and Songhay—to world economic history was consider-able. Africa was the major supplier of gold to Europe until the conquests 44 A F R IC A IN T H E WOR L D of the Americas brought in new sources in the sixteenth century. Ghana illustrates the importance to political power of controlling external connections. The emperor could ensure his cut in the trade of gold and slaves more readily than the extraction of surplus production from “his” people. He could use the profits of trade to buy slaves, who could fight on his behalf as well as produce. His wealth and military power could attract the support of young men who had become detached from or sought an alternative to their own kinship group. - eBook - ePub

Akan and Ga-Adangme Peoples

Western Africa Part I

- Madeline Manoukian(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

A number of separate» autonomous states, possessing similar social and political institutions, a common language and religion, and bound by ties of clanship, were welded into a Union under the Asantehene, whose capital was Kumasi. The Union was a loose confederation in which each state kept its own treasury, held its own religious festivals and managed its own internal affairs. By the end of the nineteenth century, partly owing to migration and partly by absorption and conquest of other tribes, the Union included the states of Kumasi (including Nkwanta and Berekum), Mampong, Juaben, Bekwai, Kokofu, Nsuta, Asumegya, Kumawu, Adansi, Offinsu, Agona, Wam-Pamu, Nkoranza, Techiman and Banda. 2 The states which were conquered and absorbed were left in possession of their lands and managed their own internal affairs. The bond between them all was common allegiance to the Asantehene. No permanent Union army was established: the different states supplied the necessary men when the need arose; all able-bodied men of each state were liable for military service. As the Chiefs provided the fighting men, they were consulted in all matters relating to war: foreign policy was the joint responsibility of all the Chiefs. Sanctions of the Union. (a) Physical force, used to prevent attempts at secession from the Union; (b) the existence of other potentially hostile states to the north and south of Ashanti gave unity and solidarity to the Union; (c) sentiments of loyalty to the Golden Stool, symbol of the unity of the Ashanti nation, and respect for the ancestors who had originated the Union, were kept up by periodic ritual ceremonies in Kumasi. The Kumasi Division In Kumasi the lineage system, on which the military organization of the other states was built up, gave way to groupings based entirely on military considerations. Instead of lineages there were military units or companies (fekuo), composed of people of different clans placed under Captains (Safohene)

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.