History

Khmer Empire

The Khmer Empire was a powerful state in Southeast Asia from the 9th to the 15th century. Centered in present-day Cambodia, it was known for its impressive architecture, including the famous temple complex of Angkor Wat. The empire also had a sophisticated system of governance and was influential in the region's art, culture, and religion.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Khmer Empire"

- eBook - ePub

- Jennifer C. Ross, Sharon R. Steadman(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

10 Empires in Southeast AsiaIntroduction

The empires in southeast Asia, particularly the last and greatest, the Khmer, were all founded within the last 2,000 years. The Khmer Empire was contemporary with Great Zimbabwe (Chapter 4 ), but the method of governance practiced in these two cultures was starkly different, though both relied heavily on the use of religion as an element of retaining leadership and control.Though the Khmer Empire is relatively recent, we know comparatively little about it due to poor preservation of non-monumental architectural remains and the total lack of any Khmer records other than building inscriptions. Nonetheless, it is clear that Khmer kings held powerful authority over a vast region of the southeast Asian mainland. Their power lay in control of a complicated bureaucracy that ensured the provision of goods and services to the king and in the Khmer king’s representation of himself to his people as divine while on earth and as an agent of the powerful Hindu gods. Obeying and pleasing the king was tantamount to showing devotion to the state’s main gods. The Khmer Empire, then, is an ideal example of the inextricable tie between power and religion found in many of the world’s ancient archaic states.Geography and Chronology

The southeast Asian mainland, today occupied by the countries of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand, is one rich in flora and fauna and criss-crossed by numerous rivers, the most substantial of which is the mighty Mekong. The topography, though friendly to successful habitation, makes archaeological research a challenge.Geography and Ecological Setting

The boundaries of the southeast Asian empires of the last two millennia are largely defined by three major rivers: the Red River in northern Vietnam, the Chao Phraya in Thailand to the southwest, and the Mekong River, which rises in Tibet and runs through the heart of the entire region (Figure 10.1 - eBook - ePub

- Peter Church(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

By then, however, the principal religious focus of Khmer society had altered. Varieties of Buddhism had long coexisted with the Hindu Devaraj cults but, during the 13th century, Theravada Buddhism won general allegiance. This form of Buddhism, originally defined in Sri Lanka and possibly Burma, was organised by its sangha (order of monks) and clear about what constituted Buddhist orthodoxy, while also being able to subsume Hindu and animist elements. It was rapidly becoming the dominant religion in mainland South‐East Asia. The concept of Devaraj, celebrated by Brahmanic officiants, would persist in Khmer society, but a godly king would now demonstrate his virtue primarily through patronage of Theravada Buddhist temples, monasteries, and schools. As a consequence, perhaps, interest in the temple‐mausoleums of former rulers declined.In the 1440s, the Khmer ruling class abandoned the Angkor region. Besides the impact of Theravada Buddhism there are other possible reasons for this shift. Court factionalism may have weakened the firm government needed for such an intricately connected “hydraulic society” to work, and hastened ecological deterioration of a region which had been intensively exploited for centuries. The general population of the area may have drifted away as the irrigation system silted up. Malaria has also been suggested as a factor in Angkor's abandonment. The best established factor in the transfer of the kingdom is the rise, from 1351, of the ambitious Thai state of Ayudhya. The Thais insistently attacked Angkor, looting it of wealth and people. A Khmer capital to the south‐east (variously in later centuries Phnom Penh, Udong, and Lovek) may have seemed more defensible than Angkor. Such cities were also nearer the sea and the booming maritime trade of 15th‐century South‐East Asia.THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA, 15TH–18TH CENTURIES

Until late in the 16th century the translated Khmer kingdom appears to have been quite strong, an equal of neighbours like Ayudhya, Lan Xang (Laos), and Vietnam. Intermittent warfare with the Thais continued, but also peaceful trade and cultural exchange. In religion, polity, and culture, the Thai and Khmer kingdoms had much in common. In 1593, however, the Thai king Narasuen attacked Cambodia as part of his strategy to reaffirm the power of Ayudhya after a devastating assault on his city by the Burmese. From this time, Cambodia slipped decisively—at least in Thai eyes—to the status of a Thai vassal state. - eBook - ePub

- Peter Church(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

sangha (order of monks) and clear about what constituted Buddhist orthodoxy, while also being able to subsume Hindu and animist elements. It was rapidly becoming the dominant religion in mainland South-East Asia. The concept of Devaraj, celebrated by Brahmanic officiants, would persist in Khmer society, but a godly king would now demonstrate his virtue primarily through patronage of Theravada Buddhist temples, monasteries and schools. As a consequence, perhaps, interest in the temple-mausoleums of former rulers declined.In the 1440s, the Khmer ruling class abandoned the Angkor region. Besides the impact of Theravada Buddhism there are other possible reasons for this shift. Court factionalism may have weakened the firm government needed for such an intricately connected “hydraulic society” to work, and hastened ecological deterioration of a region which had been intensively exploited for centuries. The general population of the area may have drifted away as the irrigation system silted up. Malaria has also been suggested as a factor in Angkor's abandonment. The best established factor in the transfer of the kingdom is the rise, from 1351, of the ambitious Thai state of Ayudhya. The Thais insistently attacked Angkor, looting it of wealth and people. A Khmer capital to the south-east (variously in later centuries Phnom Penh, Udong and Lovek) may have seemed more defensible than Angkor. Such cities were also nearer the sea and the booming maritime trade of 15th-century South-East Asia.The Kingdom of Cambodia, 15th–18th centuriesUntil late in the 16th century the translated Khmer kingdom appears to have been quite strong, an equal of neighbours like Ayudhya, Lan Xang (Laos) and Vietnam. Intermittent warfare with the Thais continued, but also peaceful trade and cultural exchange. In religion, polity and culture, the Thai and Khmer kingdoms had much in common. In 1593, however, the Thai king Narasuen attacked Cambodia as part of his strategy to reaffirm the power of Ayudhya after a devastating assault on his city by the Burmese. From this time, Cambodia slipped decisively—at least in Thai eyes—to the status of a Thai vassal state. - eBook - ePub

Cambodia’s China Strategy

Security Dilemmas of Embracing the Dragon

- Chanborey Cheunboran(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

This marked the starting point of Cambodia’s persistent quest for the survival, rather than the revival, of its past glory. Cambodia’s roots can be traced back to Funan or the “Kingdom of Mountain,” which was founded in the first century AD. It is believed that Funan controlled a large territory of “the lower valleys of the Mekong River, the area around the Tonle Sap Lake, and a part of the Mekong delta region” and imposed its suzerainty over smaller states in the northern portion of the Malay Peninsula. 3 In the sixth century, however, Funan was absorbed by another emerging Khmer state of Chenla, which during the next three centuries controlled a vast area in today’s “central and upper Laos, western Cambodian and southern Thailand.” 4 Chenla suffered from dissensions within the royal family, which resulted in the split of the Kingdom into Chenla-of-the-land and Chenla-of-the-water in the eighth century. 5 Over the next hundred years, Chenla-of-the-water was further weakened by dynastic rivalries, which enabled the Javanese – who launched a number of raids on the east coast of Indochina between 767 and 787 – to successfully impose suzerainty over the Khmer. 6 Javanese suzerainty was cast off after the ascension of Jayavarman II (802–850) to the throne of Chenla-of-the-water. Subsequently, Jayavarman reunified the Khmer kingdoms and moved the capital to Siem Reap, from where he built the Angkor Empire. During his reign, Jayavarman firmly established the concept of a unified, independent Khmer state ruled by a devaraja or God-king. 7 A sophisticated irrigation system was built to provide the economic foundation for the Empire. Monumental temples around the site of the capital at Angkor were also built. The Khmer Empire reached its apogee in the eleventh century under the rule of Suryavarman II (ca - eBook - PDF

- Peter Church(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

As a consequence, perhaps, interest in the temple-mausoleums of former rulers declined. In the 1440s, the Khmer ruling class abandoned the Angkor region. Besides the impact of Theravada Buddhism there are other possible reasons for this shift. Court factionalism may have weakened the firm government needed for such an intricately connected “hydraulic society” to work, and hastened ecological deterioration of a region which had been intensively exploited for centuries. The general population of the area may have drifted away as the irrigation system silted up. Malaria has also been suggested as a factor in Angkor’s abandonment. The best established factor in the transfer of the kingdom is the rise, from 1351, of the ambitious Thai state of Ayudhya. The Thais insistently attacked Angkor, looting it of wealth and people. A Khmer capital to the south-east (variously in later centuries Phnom Penh, Udong, and Lovek) may have seemed more defensible than Angkor. Such cities were also nearer the sea and the booming maritime trade of 15th-century South-East Asia. CAMBODIA 17 THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA, 15TH–18TH CENTURIES Until late in the 16th century the translated Khmer kingdom appears to have been quite strong, an equal of neighbours like Ayudhya, Lan Xang (Laos), and Vietnam. Intermittent warfare with the Thais continued, but also peaceful trade and cultural exchange. In religion, polity, and culture, the Thai and Khmer kingdoms had much in common. In 1593, however, the Thai king Narasuen attacked Cambodia as part of his strategy to reaffirm the power of Ayudhya after a devastating assault on his city by the Burmese. From this time, Cambodia slipped decisively—at least in Thai eyes—to the status of a Thai vassal state. Shortly after Narasuen’s attack, Cambodia demonstrated vividly a feature that would darken its history in the centuries ahead—ruling class attempts to harness foreign assistance in ruling-class rivalries. - eBook - ePub

Business Practices in Southeast Asia

An interdisciplinary analysis of theravada Buddhist countries

- Scott A. Hipsher(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The demise of Angkor is a mystery that has not been solved to the satisfaction of all historians. The Siamese (Thais), who had previously been vassals of the Khmers, apparently launched a large-scale and successful assault on Angkor around 1431, which seems to have played a part in the moving of the capital of the Khmer civilization to Phnom Penh. Other factors given for the decline of Angkor include ecological degradation and the impact of Theravada Buddhism on the population. Although conventional wisdom has been that Angkor was suddenly abandoned, evidence indicates that Angkor Thom was only abandoned in 1629, nearly 200 years after the attacks by the Siamese, and other parts of Angkor were rebuilt as late as 1747 (Tully 2005:17, 49; Vickery 2004).From the beginning of the fourteenth century until the middle of the sixteenth century, there are very few surviving inscriptions of life in the Khmer Kingdom. Although decline is the common term used to refer to this time period, Chandler (2000:78– 9) cautioned against taking an overly negative view of the era. Change from a centralized political structure that built massively in stone to a more decentralized political system may not have had a seriously negative effect on the majority of the population even if it makes this later period of less interest to historians and archeologists. However, the loss of the Saigon (Prey Nokor) and the Mekong Valley in the 1620s to the Nguyen (Vietnamese) had the effect of cutting off the Khmer Kingdom from maritime trade, which weakened the country politically and may have resulted in Cambodia losing some sovereignty to its two neighbors, Vietnam and Thailand. In general, Cambodia’s historical relations with Thailand have been different and less confrontational than its relations with Vietnam, which may be attributed to the sharing of a common religion. It has been speculated that the current situation, where the majority of the Khmer population are mostly occupied with activities related to agriculture, monastic life, and roles in the government, and where most commercial activities are carried out by ethnic minorities, can be traced back to the days before French colonization and can be partially attributed to the conversion of the population to Theravada Buddhism (Chandler 2000:77, 95, 100, 115; Tully 2005:56, 62). - (Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

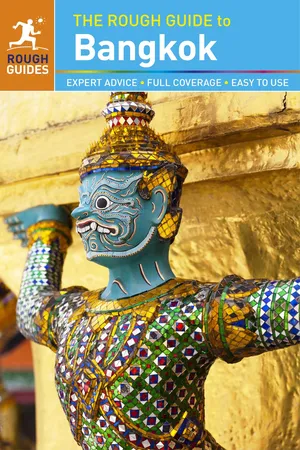

- Rough Guides(Publisher)

The empire of Angkor now stretches from Burma to Vietnam 1177 Cham invade Angkor and sack Angkor Thom The decline of Angkor Following the high-water mark of Jayavarman VII’s reign, Angkor fell into a gradual decline, with many of its dependencies in Thailand, including Sukothai and Louvo, reasserting their independence. Resurgent Thai forces subsequently launched a series of attacks, eventually capturing and sacking Angkor in 1431 , the traditional date given for the final collapse of the empire. Easy as it is to blame the Thais for the demise of Angkor, the kingdom’s actual decline was in fact probably a much more protracted affair, and the reasons for it more complicated than simple military defeat. The constant drain of money and manpower poured into temple building may have been a factor, as was the growing influence of the ascetic Theravada school of Buddhism, the very antithesis of the god-king cults which had shaped the city. The main reason for the city’s eventual collapse, however, was probably ecological, with the ever-growing population eventually causing fatal deforestation, resulting in a loss of soil fertility and a silting up of the complex hydraulic system – whose increasingly stagnant canals and reservoirs then became a DAILY LIFE IN ANGKOR Some 1200 stone inscriptions have been found in Angkor region written in Sanskrit, Khmer and (later) Pali, the classical language of Buddhism, while bas-reliefs at the Bayon provide vivid records of ordinary Khmer life. No books from the city have survived, however, and the only written account of Angkorian life is The Customs of Cambodia by Chinese traveller Zhou Daguan , who visited the city in 1295, during the later days of empire. There was no caste system at Angkor, but society was rigorously stratified at all levels from slaves, peasants and farmers up to nobles, the priestly elite and kings.- eBook - PDF

- Henri J. M. Claessen, Peter Skalnik, Henri J. M. Claessen, Peter Skalnik(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Mouton(Publisher)

5 Angkor: Society and State LEONID A. SEDOV From the purely chronological point of view the Angkorian period in the history of the Khmer people can hardly be called 'an early childhood'. The appearance on the historical map of the, in many respects, unique and, in others, typical state of Angkor was preceded by a prolonged formative period of emerging statehood of the Khmer tribes that began in the first century A.D. and eventually culminated in the establishment of the early state in its purest form that was Angkor. This process cannot be described in any detail here for reasons of space and because of the scarcity of data in general. It seems useful, however, to sketch at least a picture of what went on in the territory of the future state of Angkor during this period. 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The beginning of the new era finds the Khmer tribes at the stage of the Iron Age culture. The population, sparse as it is, is made up of tribal clan communities with strong internal kinship ties and living relatively isolated from each other, though mutually at peace. This situation changed radically after the coastal regions in the Mekong Delta came under the influence of the highly developed Indian civilization. Indian immigrants, colonists and traders brought with them their own ideas of government, 'customs and fashions', and religious symbolism. They acquainted the aborigines with various new techniques, including methods of land reclamation, and with handi-crafts and the art of war. However, the main changes in the life of the people of this coastal region were connected firstly with the introduc-tion of writing, that major tool of civilization, and secondly with the 112 Leonid A. Sedov drawing of the coastal communities into the broader sphere of interna-tional trade. These two factors radically changed the nature of the existing community of agriculturists and hunters transforming it into a nagara, or clan community with a state-like character. - eBook - ePub

- (Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Lonely Planet(Publisher)

Angkor was losing control over the peripheries of its empire. At the same time, the Thais were ascendant, having migrated south from Yunnan, China, to escape Kublai Khan and his Mongol hordes. The Thais, first from Sukothai, later Ayuthaya, grew in strength and made repeated incursions into Angkor before finally sacking the city in 1431 and making off with thousands of intellectuals, artisans and dancers from the royal court. During this period, perhaps drawn by the opportunities for sea trade with China and fearful of the increasingly bellicose Thais, the Khmer elite began to migrate to the Phnom Penh area. The capital shifted several times over the centuries but eventually settled in present-day Phnom Penh.From 1500 until the arrival of the French in 1863, Cambodia was ruled by a series of weak kings beset by dynastic rivalries. In the face of such intrigue, they sought the protection – granted, of course, at a price – of either Thailand or Vietnam. In the 17th century, the Nguyen lords of southern Vietnam came to the rescue of the Cambodian king in return for settlement rights in the Mekong Delta region. The Khmers still refer to this region as Kampuchea Krom (Lower Cambodia), even though it is well and truly populated by the Vietnamese today.In the west, the Thais controlled the provinces of Battambang and Siem Reap from 1794 and held influence over the Cambodian royal family. Indeed, one king was crowned in Bangkok and placed on the throne at Udong with the help of the Thai army. That Cambodia survived through the 18th century as a distinct entity is due to the preoccupations of its neighbours: while the Thais were expending their energy and resources fighting the Burmese, the Vietnamese were wholly absorbed by internal strife. The pattern continued for more than two centuries, the carcass of Cambodia pulled back and forth between two powerful tigers.The French in Cambodia

The era of yo-yoing between Thai and Vietnamese masters came to a close in 1863, when French gunboats intimidated King Norodom I (r 1860–1904) into signing a treaty of protectorate. Ironically, it really was a protectorate, as Cambodia was in danger of going the way of Champa and vanishing from the map. French control of Cambodia developed as a sideshow to its interests in Vietnam, uncannily similar to the American experience a century later, and initially involved little direct interference in Cambodia’s affairs. The French presence also helped keep Norodom on the throne despite the ambitions of his rebellious half-brothers. - George Coedes(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

10 concerning the southward movement of the T’ais, which has sometimes wrongly been described as an ‘invasion’. ‘It might be better to use the word “inundation” to describe the advance of this extraordinary race, for they are like water, which is fluid and yet can insinuate itself with force, which can take on the colour of any sky and the form of any channel while at the same time preserving, under different outward aspects, its essential characteristics, just as the T’ais preserved their own characteristics and their language. Now they are spread, like a vast sheet of water, all over South China, Tongking, Laos, Siam, and even as far as Burma and Assam.’The view is gaining ground that this ‘inundation’ was less a matter of large-scale migration than of a gradual infiltration of immigrants who began by holding positions of command over communities of sedentary agriculturalists, and ended by gaining control over the native peoples among whom they had settled and whose culture they had assimilated.The death of Suryavarman II, probably sometime after 1150, gave the signal for the outbreak of internal revolts which will be discussed later. His reign marks the end, not of the prosperity of Cambodia – for the end of the twelfth century and the beginning of the thirteenth saw another period of grandeur based on a new conception – but of what might be called traditional Angkor civilization, which played such an important role in the cultural development of central Indochina, and exercised a great deal of influence on that of the T’ais of the Mekong and the Menam.The brilliance of this civilization and the magnificence of its works presuppose a large and prosperous population, whose prosperity was based on the intensive agriculture made possible by the well-planned irrigation system which had brought large areas of land under cultivation.11- eBook - PDF

- (Author)

- 0(Publication Date)

- Rough Guides(Publisher)

The Khmers’ main outpost, at Lopburi, was by this time regarded as the administrative capital of a land called Syam (possibly from the Sanskrit syam , meaning swarthy) – a mid-twelfth-century bas-relief at Angkor portraying the troops of Lopburi, preceded by a large group of self-confident Syam Kuk mercenaries, shows that the Thais were becoming a force to be reckoned with. Sukhothai At some time around 1238, Thais in the upper Chao Phraya valley captured the main Khmer outpost in the region at Sukhothai and established a kingdom there. For the first forty years it was merely a local power, but an attack by the ruler of the neighbouring principality of Mae Sot brought a dynamic new leader to the fore: the king’s nineteen-year-old son, Rama, defeated the opposing commander, earning himself the name Ramkhamhaeng , “Rama the Bold”. When Ramkhamhaeng himself came to the throne around 1278, he seized control of much of the Chao Phraya valley, and over the next twenty years, more by diplomacy than military action, gained the submission of most of Thailand under a complex tribute system. Although the empire of Sukhothai extended Thai control over a vast area, its greatest contribution to the Thais’ development was at home, in cultural and political matters. A famous inscription by Ramkhamhaeng, now housed in the Bangkok National Museum, describes a prosperous era of benevolent rule: “In the time of King Ramkhamhaeng this land of Sukhothai is thriving. - eBook - PDF

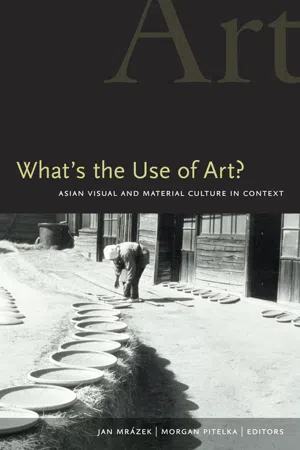

What's the Use of Art?

Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context

- Jan Mrazek, Morgan Pitelka(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- University of Hawaii Press(Publisher)

seven | ashley thompson Angkor Revisited The State of Statuary Cambodia’s kings are forever returning to Angkor. The foundation of the Angkorian empire was itself constituted by a spectacular return, a return that set the cycle in motion, to deeply mark the Khmer collective memory for centuries to come.1 In a remarkable discursive return to roots, an eleventh-century court Brahman recorded in stone the legendary return of an exiled prince to Cambodia in the eighth century.2 This was Jayavarman II, who, our early historian tells us, concluded a series of military campaigns with a series of religious campaigns, claiming to restore order to the land and then reclaim the throne. Building temples in the east, the south, the west, and the north of the broad plain, Jayavarman II was reputed to have physically and symbolically circumscribed the space that is known today as Angkor (fig. 7.1). For the next five centuries Cambodian kings and court officials built and restored temples to the gods, their ancestors, and themselves in and beyond Angkor. The stat-ues now exhibited in museums, conserved in warehouses, or sold on the inter-national market once peopled these temples. “Bodies of glory,” ( yaśasarīra ) or “ dharma ,” as they are often called in stone inscriptions of the time, these im-ages portray gods, kings, queens, and other officials. After the fall of Angkor in the fifteenth century and the permanent removal of the capital to the south, Khmer royalty repeatedly returned to Angkor’s temples, paying their respects to gods and ancestors, restoring old statues and erecting new ones. And they continue to return, with unflagging assiduity. Of course such royal returns constitute religious, personal, or “cultural” events, but at the same time they have political implications. The king’s return to Angkor is a performative act: it promotes the stability of a certain political-cultural continuity only insofar as it is itself an example of such continuity.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.