History

Angkor

Angkor was a powerful and influential ancient city in the Khmer Empire, located in present-day Cambodia. It was the political, religious, and cultural center of the empire, known for its impressive architecture, including the iconic Angkor Wat temple complex. At its peak, Angkor was one of the largest pre-industrial cities in the world, showcasing the Khmer civilization's advanced urban planning and engineering skills.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Angkor"

- eBook - PDF

What's the Use of Art?

Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context

- Jan Mrazek, Morgan Pitelka(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- University of Hawaii Press(Publisher)

The Angkor region is situated in Cambodia’s northern Siem Reap Province, to the northeast of the Tonle Sap lake and southwest of the Kulen mountains. Of-ficially defined by zoning regulations adopted in 1994 with reference to colonial and post-Independence legislation, the central Angkor Park is in effect an open-air and, to some extent, living museum. Most archaeological vestiges — temples, statuary, and civil works — date to the period of the Angkorian empire, from the ninth to fifteenth cen-turies. (For an English translation of the 1994 zoning regulations, which constituted the first legal act to be signed by King Sihanouk in his role as head of the first postwar elected government, see Ang Chouléan, A. Thompson, and E. Prenowitz, Angkor: A Manual for the Past, Present and Future , APSARA and UNESCO, Phnom Penh, 1995.) (Map courtesy of Kim Samnang, APSARA Authority, Angkor) Angkor Revisited | 181 movement that can hold both conservative and innovative potential in a pow-erful though fragile balance. A telling contemporary example is that of King Sihanouk’s return to Angkor after the coup d’état of “July 5–6,” 1997.3 This return after a long absence no doubt signified many things in many different arenas. But from a historical point of view, the king was participating in an an-cient and august tradition by making the pilgrimage to the seat of the ancient empire to receive his adoring people and, in his words, to “pay [his] respects to the statues,” while hoping to reconcile warring factions and re-establish peace. The king’s return to Angkor was a kind of real-life metaphor for another “re-turn,” as he himself put it. “I want to return to the status quo ante,” the king said, “with genuine respect for human rights, genuine freedom of the press, peace and democracy.”4 In Cambodia, art, religion, and politics have always gone hand in hand. - eBook - ePub

Asia’s Heritage Trend

Examining Asia’s Present through Its Past

- Jongil Kim, Minjae Zoh, Jongil Kim, Minjae Zoh(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Part Three Archaeological advances in Southeast Asia 10 The people of Angkor Alison Kyra Carter and Miriam T. Stark DOI: 10.4324/9781003396765-13 Introduction The UNESCO World Heritage site of Angkor is located in northwest Cambodia on the edge of the Tonle Sap Lake floodplain. The Angkor Civilization, sometimes also called the Khmer civilization or Khmer Empire after the major ethnolinguistic group, was the dominant political force in mainland Southeast Asia from the ninth to fifteenth centuries ce. An eleventh-century inscription describes the establishment of the Angkor kingdom by Jayavarman II in 802 ce (Coedès and Dupont, 1943). Over six centuries, the capital expanded and grew into a massive agro-urban centre that at its height in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries ce may have had a population of 700,000–900,000 people (Carter et al., 2021, Klassen et al., 2021). Angkor has been the focus of Western academic research since the 19th century, when French and Khmer scholars worked to restore temples, build an art historical chronology, and translate the Khmer and Sanskrit inscriptions located on stele and temple doorways (École française d’Extrême-Orient, 2010, Clémentin-Ojha and Manguin, 2007). This scholarship was foundational to understanding the history of Angkor’s rulers and the development of the Angkor Empire. At the same time, these French colonial interpretations of Angkor actively shaped perceptions of Cambodian arts and heritage that persist today (Burgess, 2021, Edwards, 2007, Muan, 2001). There is still much to be learned about the rest of Angkor’s population; the people who farmed rice in Angkor’s sprawling rice fields, fished the rich Tonle Sap Lake, made Angkor’s ubiquitous stoneware ceramics, built Angkor’s famous stone temples, and worked to keep the temples running. Our chapter reviews historical, art historical, ethnographic, and archaeological data to provide a snapshot of life in Angkor in the city, countryside, and provinces - eBook - PDF

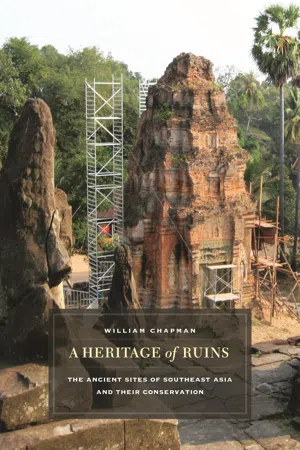

A Heritage of Ruins

The Ancient Sites of Southeast Asia and Their Conservation

- William R. Chapman(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- University of Hawaii Press(Publisher)

This all ended in 1975, with the dramatic fall of Cambodia to radical communist forces, titled by the French the Khmer Rouge and led by the despot Pol Pot. The Khmer Rouge too saw Angkor as a symbol of the country’s former glory, adding—as had their predecessors— the iconic towers of Angkor Wat to the flag of Democratic Kampuchea. With restoration of an elected democratic government in 1991, the long civil war and period of Vietnamese occupation finally concluded, allowing for increasing normalization in subsequent years. The resumption of work at Angkor went hand in hand with greater political stabil-ity. First, the Archaeological Survey of India started work afresh at Angkor Wat. Other countries followed: Poland, Hungary, the United States (via the nongovernmental World Monuments Fund), and then, as the political climate changed, Indonesia, France, West Ger-many, Italy, Japan, and China. With primary support coming from France and Japan, as well as from increasing tourism revenues, the work at Angkor has progressed over the past two decades to a point of unusual competency. Cambodia has become a dynamic vortex of archaeological and conservation practice. When experts talk about conservation in the region, they are really talking about Cambodia. Funan and Chenla The ancient history of Cambodia begins with one of the earliest Indianized cultures, tra-ditionally identified as Funan, centered in the southern parts of what is now Vietnam and extending west as far as Thailand. Probably the descendants of early Neolithic inhabitants Figure 3.1. ( Facing page ) Map of Cambodia, 1991. 1. Óc Eo (Vietnam) 6. Banteay Srei 13. Kampong Kdei Bridge 2. Angkor Borei 7. Banteay Chhmar 14. Koh Ker 3. Kulen Mountains 8. Prasat Preah Vihear 15. Wat Eek 4. Roluos (Phnom Bakong, 9. Preah Khan Kampong Svay 16. Phnom Chisor Lolei, and Preah Ko) 10. - (Author)

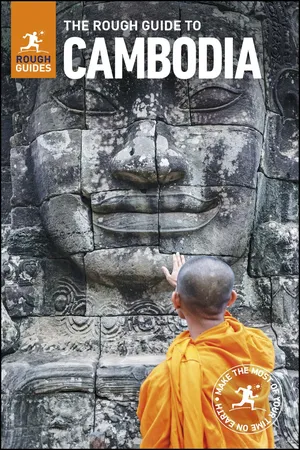

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Rough Guides(Publisher)

The empire of Angkor now stretches from Burma to Vietnam 1177 Cham invade Angkor and sack Angkor Thom The decline of Angkor Following the high-water mark of Jayavarman VII’s reign, Angkor fell into a gradual decline, with many of its dependencies in Thailand, including Sukothai and Louvo, reasserting their independence. Resurgent Thai forces subsequently launched a series of attacks, eventually capturing and sacking Angkor in 1431 , the traditional date given for the final collapse of the empire. Easy as it is to blame the Thais for the demise of Angkor, the kingdom’s actual decline was in fact probably a much more protracted affair, and the reasons for it more complicated than simple military defeat. The constant drain of money and manpower poured into temple building may have been a factor, as was the growing influence of the ascetic Theravada school of Buddhism, the very antithesis of the god-king cults which had shaped the city. The main reason for the city’s eventual collapse, however, was probably ecological, with the ever-growing population eventually causing fatal deforestation, resulting in a loss of soil fertility and a silting up of the complex hydraulic system – whose increasingly stagnant canals and reservoirs then became a DAILY LIFE IN Angkor Some 1200 stone inscriptions have been found in Angkor region written in Sanskrit, Khmer and (later) Pali, the classical language of Buddhism, while bas-reliefs at the Bayon provide vivid records of ordinary Khmer life. No books from the city have survived, however, and the only written account of Angkorian life is The Customs of Cambodia by Chinese traveller Zhou Daguan , who visited the city in 1295, during the later days of empire. There was no caste system at Angkor, but society was rigorously stratified at all levels from slaves, peasants and farmers up to nobles, the priestly elite and kings.- No longer available |Learn more

Urban Development in the Margins of a World Heritage Site

In the Shadows of Angkor

- Adèle Esposito(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Amsterdam University Press(Publisher)

They play a part in the cultural re-imagining and material shaping of Siem Reap: 150 hotels were built between 1992 and 2008 and their number never ceases to grow. Nevertheless, with a few remarkable exceptions (Sanjuan et al., 2003; Peleggi, 2005; Teo and Chang, 2009), tourism architecture has rarely been a subject of academic interest. This chapter aims to contribute to the analysis of tourism architecture as the object of convergence of various layers of meaning interconnected through local collections and combinations of architectural elements and spatial features. 4.1 Angkor: From discovery to commodity Angkor was almost unknown to the West in the second half of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, Portuguese and Spanish travel writers from the sixteenth century 2 had borne witness to the existence of the ancient Khmer kingdom. They had portrayed a mythical city hidden deep in the forest, which the Cambodian King Sâtha had rediscovered after the abandonment of the capital in the fi fteenth century (Groslier, 1958; Chandler, 2008). In 2 During the second half of the sixteenth century, European missionaries, merchants, and adventurers were present at King Satha’s court. The king surrounded himself with foreign intermediaries who helped him negotiate with the Portuguese colonizers in Malaysia and the Spanish colonizers in the Philippines. The number of Europeans at the royal court decreased in the eighteenth century in Cambodia as well as in nearby Laos and Siam (Chandler, 2000). 238 URBAN DEVELOPMENT IN THE MARGINS OF A WORLD HERITAGE SITE fact, Angkor had never been abandoned, as Khmer villagers living nearby had always taken care of the temples and viewed them as sacred places (Baille, 2007). Later, the French Sinologist Albert Rémusat translated and published the story of the visit that Tcheou Ta-Kouan, a Chinese ambassador, paid to Angkor in 1296-1297 (Fournereau and Porcher, 1890). - eBook - PDF

- Henri J. M. Claessen, Peter Skalnik, Henri J. M. Claessen, Peter Skalnik(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Mouton(Publisher)

5 Angkor: Society and State LEONID A. SEDOV From the purely chronological point of view the Angkorian period in the history of the Khmer people can hardly be called 'an early childhood'. The appearance on the historical map of the, in many respects, unique and, in others, typical state of Angkor was preceded by a prolonged formative period of emerging statehood of the Khmer tribes that began in the first century A.D. and eventually culminated in the establishment of the early state in its purest form that was Angkor. This process cannot be described in any detail here for reasons of space and because of the scarcity of data in general. It seems useful, however, to sketch at least a picture of what went on in the territory of the future state of Angkor during this period. 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The beginning of the new era finds the Khmer tribes at the stage of the Iron Age culture. The population, sparse as it is, is made up of tribal clan communities with strong internal kinship ties and living relatively isolated from each other, though mutually at peace. This situation changed radically after the coastal regions in the Mekong Delta came under the influence of the highly developed Indian civilization. Indian immigrants, colonists and traders brought with them their own ideas of government, 'customs and fashions', and religious symbolism. They acquainted the aborigines with various new techniques, including methods of land reclamation, and with handi-crafts and the art of war. However, the main changes in the life of the people of this coastal region were connected firstly with the introduc-tion of writing, that major tool of civilization, and secondly with the 112 Leonid A. Sedov drawing of the coastal communities into the broader sphere of interna-tional trade. These two factors radically changed the nature of the existing community of agriculturists and hunters transforming it into a nagara, or clan community with a state-like character. - eBook - ePub

- Mitch Hendrickson, Miriam T. Stark, Damian Evans, Mitch Hendrickson, Miriam T. Stark, Damian Evans(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Therefore, historical and archaeological evidence indicates a decline in the population of the Angkor area of around two orders of magnitude between the 13th and 19th centuries, concurrent with seismic changes in the social, political, and cultural landscape of the region. At the same time, we should move beyond problematic notions of ‘collapse’ and the ‘rise and fall of civilisations’ while recognising that understanding the processes at work here provides us with critical insights into long-term socio-cultural trajectories and the making of modern Southeast Asia.Perspectives on Collapse

The reasons for the ‘collapse’ of Angkor have long fascinated observers, who typically infer from the existence of massive temples that Angkor had an extremely large population that was overwhelmed and greatly diminished by external environmental or military pressures, or some combination of the two. For instance, Delaporte (1880 , 39) assumed that Angkor was home to ‘millions’. Indeed, with only two notable exceptions (Coe 1957 , 1961 ; Miksic 2000 ), the idea that Angkor was a populous city has been the dominant one in the literature since the mid-1800s. Notwithstanding persistent difficulties in defining exactly where the ‘urban’ space of Angkor begins and ends (see Evans et al. 2023 , this volume), it is now reasonably clear that the Greater Angkor landscape was home to between 700,000 to 900,000 people at its height (Klassen et al. 2021b). It is worthwhile, therefore, to re-assess traditional theories of ‘collapse’, which since the 1970s have tended to converge around a population estimate of around a million or so inhabitants (Groslier 1979 ).Conflict

The first detailed European accounts of Angkor in the 19th century drew on local histories, myths and legends, and evidence from Ayutthayan and Cambodian chronicles to argue that the demise of Angkor and the Khmer Empire was due to military conflict with the neighbouring Ayutthayan civilisation ( Briggs 1948 ; Brotherson 2019, 10–16; Vickery 1977 - eBook - PDF

- Philippe Peycam Peycam, Shu-Li Wang, Michael Hsiao(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute(Publisher)

4 The International Coordinating Committee for Angkor: A World Heritage Site as an Arena of Competition, Connivance and State(s) Legitimation * Philippe Peycam Angkor, a jewel of the Cambodian heritage, has become a shared concern. The interest of the international community has been a turning point in the history of Cambodia. (UNESCO 1993, p. 34) One year before these self-congratulatory lines were written, the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) listed the archaeological and monumental complex of Angkor in Cambodia as a World Heritage Site. The listing process had closely paralleled the negotiations that led to the Paris Agreements in 1991 and thus to the * First published in SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 31, no. 3 (2016). The International Coordinating Committee for Angkor 79 unprecedented post-conflict mission in the country led by the United Nations. The United Nation’s Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) sought to restore the political integrity of the country following decades of war and isolation. In this context, UNESCO’s recognition of Angkor and its significance symbolized the return of Cambodia to the international stage, while the plan for the management of the site was part of the process of political and economic reconstruction of the country. A number of institutional “stakeholders” 1 were involved in the listing. They were for the most part members of the “international community”, which in the UN diplomatico-bureaucratic jargon signifies primarily representatives of member states. Also, and in UNESCO’s language, the listing of Angkor corresponded to the recognition that the site was of “outstanding” and “universal” value (UNESCO 1992, pp. 5–6). Following the recognition of Angkor as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, an international “campaign” to conserve it was launched at a conference held in Tokyo in 1993. 2 Twenty-nine countries and eight organizations attended this event. - eBook - PDF

- Mark Juergensmeyer, Wade Clark Roof, Mark K. Juergensmeyer, Wade Clark Roof(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

171 C AIRO See Egypt C AMBODIA The religious culture of the Southeast Asian nation of Cambodia and the expanding Cambodian diaspora draws from a rich and dynamic Buddhist and Hindu heritage that is multifaceted, resilient, and unique. Living at the crossroads of Southeast Asia for centuries, the Khmer people of Cambodia both received from and contributed to many world cultures and continue to do so both in their home-land and in the many parts of the world where they have settled. The grand temples of Angkor Wat, Bayon, Preah Vihear, Koh Ker, and several others incorporate ideas from Indian traditions and share the architectural idiom of other monuments in Southeast Asia but in the end are uniquely and dis-tinctively Khmer. Khmer dances showcasing stories from the epic Ramayana and other compositions include narratives known in India as well as oth-ers that are unknown there. Since the 20th cen-tury, there has been a distinctly transnational trend, as communities of the Cambodian dias-pora, which now flourishes in America and in parts of Europe, regularly invite dancers and reli-gious personnel from the home country and also celebrate festivals to showcase their culture. Cambodia is about 95% Theravada Buddhist; Muslims and Christians form most of the religious minority population. The early recorded history of Cambodia as found in Chinese sources speaks about the Funan kingdom (third to fifth centuries CE) and the Zhenla kingdom—which may have been a collective of smaller states—in the sixth and seventh centuries CE. Extensive contact with many parts of the world is seen even at this early stage. Early inscriptions dating possibly back to the late fifth or early sixth centuries tell us about rulers with Indian/Hindu names with sectarian Vaishnavite and Shaivite affiliations. While Mahayana Buddhism was prevalent, most kings seem to have been, at least nominally, followers of the Hindu god Shiva. - eBook - PDF

Cambodge

The Cultivation of a Nation, 1860–1945

- Penny Edwards(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- University of Hawaii Press(Publisher)

2 Urban Legend Capitalizing on Angkor On moving from Phnom Penh to the Métropole in the 1910s, a teenager of royal descent named Atman (Khmer for “soul”) wrestles a fit of depression encapsu-lating many of the contradictions inherent in colonial and postcolonial visions of the Cambodian nation. As she travels through the streets, eyeing major monuments, the immensity of her surroundings overwhelms her, stoking deep emotions and spark-ing a vision in which “all the capitals of my Khmer ancestors” issue forth from Paris. On passing the Seine, the Mekong floods her soul. “Ordinarily,” she ponders, “though it is their only valid measure, Asiatics in Europe do not immediately perceive this time of their ancestors, of which they were ignorant in Cambodia. They must first be transfused with the earth of Europe . . . . It is in absorbing Europe’s grandeur that they bring forth the grandeur of Asia.” Her lungs have barely filled with Parisian air when, gazing at the towers of Notre Dame, she issues a “long, low, heartrending cry.” This, she tells us with the clinical detachment of an obstetrician, was “my soul, giving birth to Angkor Wat.” The “grandeur of Angkor” chokes her, “demanding of me things beyond my age,” and, with poignant prescience, she wonders whether the weight of this Angkorean epoch will one day “destroy my future society.” Atman is a fiction. The chief protagonist of a novel The Last Concubine (1942) by the Franco-Cambodian writer Pierrette Guesde (also known as Makhâli Phal), she is the time-travelling daughter of the Khmer emperor Jayavarman VII. Her attempts to adapt to modernity are strained by the ever-present shadow of her ancestry and are informed by her encounters with another character: the recently renovated capital of Phnom Penh.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.