History

Hangzhou

Hangzhou is a city in China with a rich historical significance. As the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty, it was a major political and cultural center. Renowned for its scenic West Lake and as a hub of trade and commerce, Hangzhou played a pivotal role in the development of Chinese civilization and continues to be a significant cultural and economic hub today.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

6 Key excerpts on "Hangzhou"

- No longer available |Learn more

Tasting Paradise on Earth

Jiangnan Foodways

- Jin Feng(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- University of Washington Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 4 Hangzhou The Fashionable CapitalT HE name Hangzhou immediately conjures up images of great natural beauty and cultural richness. After all, it boasts West Lake, the topic of numerous classical poems and essays throughout Chinese history; the “Ten Scenes of West Lake,” which include tourist favorites such as the Bai Causeway and the Su Causeway, built on the orders of poet and official Bai Juyi (772–846) and Su Shi; and popular stories, folk tales, and legends associated with Hangzhou as capital of the Wuyue kingdom in the Five Dynasties period (907–60) and later of the Southern Song.Compared to Suzhou, the other Chinese “paradise on earth,” which prides itself on its preservation of an uninterrupted history and pristine Jiangnan traditions, Hangzhou can lay claim to a past that exposed residents to both northern and southern Chinese culinary influences, which in turn bred eclectic food tastes. With Hangzhou assuming more administrative prominence as the provincial capital of Zhejiang, its restaurant industry fully embraces a market economy. In addition to the mercantile tradition of Zheshang (Zhejiang merchants), which advocates entrepreneurial spirit, the municipal government also feels a self-conscious need to lead the whole province through its example of carrying out the development-oriented economic policies of the state.1 Consequently, Hangzhou restaurants’ push for growth through enfranchisement and construction of food processing plants, and expansion in lines of processed and packaged foods has accelerated even more than in Suzhou.Local restaurateurs ingeniously tap into Hangzhou’s history as the capital of the Southern Song and at times evoke culinary traditions even more distant and misty than those of late imperial Suzhou. The municipal government and local entrepreneurs have long capitalized on Hangzhou’s history. Opening in 1996, the Song City (Song Cheng) Theme Park has now developed into a privately owned corporation with the name Song City World Land, which has built branches at famous tourist sites in other parts of China, including in Sanya, Lijiang, and Jiuzhaigou, advancing the Disneyfication of Hangzhou’s imperial heritage. Claiming to have combined “culture and tourism,” the theme park, which attracts an annual crowd of more than six million tourists, offers daily “romantic shows” introducing the culture of the Southern Song, various amusement parks featuring waterslides among other attractions, and a five-star hotel. In 2006, Song City also hosted the World Leisure Exposition supported by Xi Jinping, then the general secretary of the Zhejiang CCP committee, and purportedly “heralded the beginning of China’s leisure industry.”2 The city government also built a Southern Song Imperial Street based on archeological findings.3 Opened for business in 2009, the replica features historical buildings and museums but defines its mission as generating commerce and tourism. Thus, “old and famous” local shops such as Zhang Xiaoquan Scissors, Wang Xing Ji Fans, Qingyu Tang (the Hall of Plenty) Herbal Medicine, and Wufang Zhai (Five Fragrances House), a Zhejiang-originated maker of specialty dumplings (zongzi ), sit side by side with foreign chains including McDonald’s, Dairy Queen, Hä - eBook - ePub

- Jing Xie, Tim Heath(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

From the above description, it is clear that individual households could freely engage with Imperial Street by selling their services and goods. Driven by the common pursuit of commercial advancement, multiple social functions were therefore evident on Imperial Street. There was an intertwining of political and economic forces together with governmental and individual affairs. It is safe to assume that the barriers installed to eliminate the traffic were limited only to the front portion of the street connecting the Imperial Palace, therefore only slightly hampering the functioning of business activity. The physical demarcation of social hierarchy in the public street, that is, the imperative of differentiating the members of imperial court from the commoners, diminished further during the Southern Song period.The court was forced to flee from Kaifeng after it was conquered by the Jurchens in 1127 and after a prolonged struggle, the emperor Gaozong (高宗) officially denoted Hangzhou as the capital city in 1138.7 Its name was then changed to Lin’an (临安) which literally means a temporary settlement, reflecting the desire to recover the lost territory. As a result, Lin’an became the politic, economic and cultural centre of the Southern Song dynasty for about 140 years. Prior to becoming the capital known as Lin’an, Hangzhou was a prefecture city of the Northern Song dynasty, as well as the capital of the Wuyue Empire during the Five Dynasties (907–960). As such, it had enjoyed great prosperity which was further enhanced after its sanctification.8 Hangzhou’s pre-eminence over other cities in terms of commercial prosperity is acknowledged as the key factor leading to the final decision by the court regarding the options for relocation from Kaifeng.The Southern Song Imperial Palace in Hangzhou was built on the site of the existing elevated prefecture compound which was backed by the Phoenix Mountain in the south of the city. Compared to other capital cities (e.g. Chang’an, Luoyang and Kaifeng) in the preceding dynasties, the layout of Hangzhou was circumstantial. First and foremost, the city itself was shaped by the natural topography, that is, West Lake to the west and the Qiantang River to the east, thereby exhibiting an irregular and slender shape, in striking contrast to the ideal quadrangular form (Figure 3.3 ). The extreme southern location of the Imperial Palace also reflected the court’s fear of military invasions from the north. However, a sense of discretion was well disguised by literature that eulogised the site selection on the basis of the city’s natural topography. Indeed, as the Song scholar Zhao Yanwei (赵彦卫) stated in Yunlu manchao - Andreas N. Angelakis, Larry W. Mays, Demetris Koutsoyiannis, Nikos Mamassis(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- IWA Publishing(Publisher)

Hangzhou had become unprecedentedly prosperous when the Southern Song Dynasty moved its capital there. According to Meng Liang Lu , a detailed description of the society and economy, as well as the urban life of Hangzhou, the population of Hangzhou at that time was over one million. The urban water supply still depended on the West Lake. In addition, canals built in the Northern Song Dynasty were expanded. According to historical records, Hangzhou City in the Southern Song Dynasty had a total of 22 rivers, which included the four major inner city rivers Maoshan, Yanqiao, Shi and Qinghu rivers, 10 in the eastern city, 6 in the northern city and 2 in the western city. These rivers connected the Qiantang River in the south with the Jiangnan Canal and Tai Lake basin in the north. The West Lake together with those canals comprised the entire layout of the water supply system of Hangzhou in the Southern Song Dynasty (Figure 8.13). Figure 8.13 West Lake and channels in Hangzhou (Southern Song Dynasty) 1. Yanqiao River, 2. Caishi River, 3. Shi River, 4. Qinghu River (Steinhardt, 1990) History of water supply in pre-modern China 183 8.2.8 Zhongdu / Dadu / Beijing (Liao, Jin, Yuan, Ming, Qing Dynasties) The City of Beijing has a long history. In 936 AD, the Taizong Emperor of the Liao Dynasty (Kitan Empire) named Beijing as the second capital of the empire and then renamed it Nanjing (Southern Capital) or Yanjing. In 1153 AD, the Jin Dynasty (Jurchen Empire) moved its capital to Yanjing and renamed the city Zhongdu (Central Capital). Since then, Beijing served in succession as the capital of the Jin, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties and became the centre of power of Imperial China for more than 700 years (Chen, 1983) (Figure 8.14). Situated in the northern part of the North China Plain, Beijing is surrounded by mountains on the north, northwest and west sides. Major rivers flowing around the city include the Yongding and Chaobai rivers.- eBook - ePub

Cities in China

Recipes for economic development in the reform era

- Jae Ho Chung(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

During the southern Song dynasty, a school of learning emerged in Wenzhou known as the Yongjia school. It criticized the hegemonic Confucian value system and proposed more attention to industry, commerce and profit in order to enrich the country. This was partly an ideological reflection of the flourishing state of local industry and commerce at the time. At the end of the nineteenth century three local scholars, known as the ‘three gentlemen of Dong Ou’ (East Wenzhou), reiterated this basic position. 53 This distinctive cultural and ideological tradition has provided a basis for the entrepreneurial spirit of the people of Wenzhou, which has served them well in the reform period. Semi-given factors Preferential policies In its strategic pursuit of reform and opening to the outside world, the Chinese government has, since the late 1970s, granted a series of preferential policies to assist in local development, principally in the favourably located and endowed coastal region. Both Hangzhou and Wenzhou have been the recipients of such privileged treatment. Wenzhou was included in the fourteen coastal open cities declared in 1984 solely due to the accident of its location, and presumably because Zhejiang was entitled to two cities in the list and, after the logical first choice of Ningbo, Wenzhou had no competitors for second place. This is stark evidence of the state of underdevelopment of Zhejiang’s coastal regions. On the other hand the preferential policies which have been bestowed on Hangzhou have less to do with its location, although this has not been an unimportant consideration, but more to do with the stature the city possesses in Chinese national consciousness, history and culture. During the almost half-century of the PRC’s existence, as was pointed out above, the city has also become the economic centre of Zhejiang and thus can press its claim for favourable treatment from the centre with greater justification - eBook - PDF

Senses of the City

Perceptions of Hangzhou and Southern Song China, 1127–1279

- Joseph S. C. Lam, Shuen-fu Lin, Christian de Pee, and Martin Powers(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- The Chinese University of Hong Kong(Publisher)

West Lake has the foremost scenery in the realm, perfect in the morning and the evening, in bright weather and in rain, and in all four seasons. The people of Hangzhou therefore roam the lake at every time of the year, although revelers are especially numerous during the spring. . . . Here one may see the inhabitants of the capital contract marriages or celebrate the end of the year, gather with their families or send off the dead to be buried, discuss sutras or sacrifice to the gods. One may see arrangements for an appointment to an official post or for a bestowal of imperial grace, commissions by the imperial court or by the central government, noble eunuchs and prominent officials, great merchants and powerful persons, a companion bought for a thousand pieces of gold and gamblers staking a million. One may even see smitten lads and lovesick girls, and secret assignations and illicit gatherings. —— Zhou Mi 周密 (ca. 1280 – 1290 ) 1 西湖天下景,朝昏晴雨,四序總宜。杭人亦無時而不遊,而春遊特盛焉。 ……而都人凡締姻賽社、會親送葬、經會獻神、仕宦恩賞之經營、禁省 臺府之囑託、貴璫要地、大賈豪民、買笑千金、呼盧百萬、以至癡兒騃 子、密約幽期,無不在焉。 SEVEN Nature’s Capital: The City as Garden in The Splendid Scenery of the Capital ( Ducheng jisheng , 1235 ) Christian de Pee 180 Christian de Pee in the preface to his Splendid Scenery of the Capital ( Ducheng jisheng 都城紀勝 , 1235 ), the pseudonymous author, the Codger Who Irrigates His Own Garden (Guanpu naide weng 灌圃耐得翁 ), compares his work to the Record of Famous Gardens in Luoyang ( Luoyang mingyuan ji 洛陽名園記 , ca. 1095 ) by Li Gefei 李格非 (d. 1106 ). - eBook - PDF

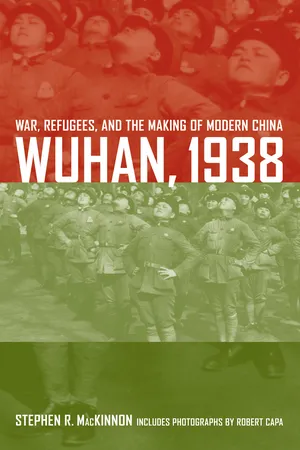

Wuhan, 1938

War, Refugees, and the Making of Modern China

- Stephen R. MacKinnon(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

THE INVENTION OF MODERN WUHAN Modern Wuhan’s identity grew out of a deeply rooted but divided his-tory that began with the political centrality of Wuchang. Since at least the Han dynasty, Wuchang had been strategically important because of its location at the Yangzi’s juncture with the Han River. Wuchang was the capital of Hubei Province, one of China’s richest and most populous provinces, and since the Ming period, its scholar-officials had overseen the entire Huguang region (Hubei and Hunan). The Huguang governor-general was arguably the third most important provincial official in the Qing empire (the first being the Zhihli governor-general, who oversaw the region around Beijing). Political importance made Wuchang an in-tellectual and educational center as well, the place where student candi-dates prepared for and took the civil service examinations. Laid out as an administrative city on the southern bank of the Yangzi, its towering walls projected political power and protected the city from flooding. By N 3 2 1 4 Y a n g z i R i v e r Y a n g z i R i v e r P L AN N E D EX P A N S I O N H a n R i v e r Foreign Racetrack Chinese Chinese Racetrack Racetrack Chinese Racetrack Beijing-Hankou Railroad Wuchang-Changsha-Guangzhou Railroad Foreign Concession Jianghan Road HANYANG HANKOU WUCHANG Arsenal Arsenal Arsenal Foundry Water tower Customs house Wuhan University (East of Wuchang) Changchun Temple Completed road Proposed road Bridge Railroad station City wall 1 2 3 4 0 .5 1 mi MAP 2. WUHAN, CA. 1927. BASED ON MAPS IN SU YUNFENG (1981), PI MINGXIU (1993), AND SHINA SHOBETSU ZENSHI (1917–20). REPRODUCED FROM MACKINNON, “WUHAN’S SEARCH FOR IDENTITY” (2000), WITH PERMISSION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS. 8 WUHAN BEFORE THE WAR function and design, it fit the traditional Chinese urban model in which the role of commerce was secondary. Across from Wuchang, at the northwest juncture of the Han andYangzi rivers, lay Hanyang.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.