Technology & Engineering

Pyramids of Giza

The Pyramids of Giza are ancient monumental structures located in Egypt, consisting of three main pyramids built as tombs for the pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. These pyramids are renowned for their impressive engineering and construction techniques, including the precise alignment of the structures with the cardinal points of the compass and the use of large stone blocks in their construction.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

9 Key excerpts on "Pyramids of Giza"

- eBook - ePub

- James Baikie(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

CHAPTER IV THE PYRAMIDS AND THEIR EXPLORERS DOI: 10.4324/9780203040485-4 O F all the works of man there is none which has attained such lasting and universal fame as the group of buildings known as the Pyramids of Gizeh. For the best part of five thousand years this group of mighty structures has been one of the wonders of the world, and the theories which have been framed to account for their existence have been more numerous than the Pyramids themselves. Egypt has many buildings far more beautiful, and perhaps as wonderful; but the Pyramids are, to the great majority of people, the characteristic buildings of the land, and whenever Egypt is named there rises before the mind at once a vision of three vast bulks of masonry squatting defiantly on the rising ground above the Libyan desert, as though challenging Time himself to make any impression on their stupendous mass. “All things dread Time,” it has been said, “but Time itself dreads the Pyramids”; and the very exaggeration testifies to the profound impression which their bulk and strength have made upon the mind of man - eBook - ePub

Antiquity Imagined

The Remarkable Legacy of Egypt and the Ancient Near East

- Robin Derricourt(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

CHAPTER 2

PYRAMIDOLOGIES AND PYRAMID MYSTERIES

The pyramids of Egypt have long attracted some of the most extreme ‘alternative' interpretations of ancient Egypt – an exceptionally broad range of mutually contradictory ‘explanations' which have attracted the designation of ‘pyramidiocy' from their critics.To academic specialists, the pyramids were originally built as the monuments, first seen about 2550 BCE in Old Kingdom Egypt, that mark royal burial places, constructed by Egyptian labour, designed by Egyptian engineers and architects working for a powerful centralised pharaonic state within an ideology that paid particular attention to the afterlife. The best known and most visited of Egypt's numerous pyramids are those at Giza, on the desert edge 20 kilometres south-west of Cairo, and the largest of these is the so-called Great Pyramid, that of pharaoh Khufu (the Cheops of classical texts), from around 2520 BCE . Built from limestone blocks and some internal granite with a hidden underground chamber dug into the bedrock, it is the only survivor of the ancient Seven Wonders of the World.But there is a large and significant set of traditions which provide dramatically alternative interpretations of the pyramids. Typically – though not always – these disengage their subject from the context of Egyptian society. Some concentrate only on the Giza pyramids, and many have developed and applied their ideas exclusively on the Great Pyramid.The range and diversity of alternative pyramidologies is substantial: at least 30 different uses or meanings have emerged over two millennia, with a burst of new approaches in recent decades. Most are incompatible, though occasionally an author will suggest several possibilities. In these approaches, the Great Pyramid may be anything but just a royal tomb of an Old Kingdom pharaoh. It may be a repository for ancient knowledge, encoded in its measurements or buried within its structure. This may be knowledge about the dimensions of the earth, or about the wider universe, or time past and future, or mathematics, or spiritual knowledge. It may hold secrets about physical or biological science and be able to effect changes to physical matter or biological materials. It may be a tool for predicting the future, for astronomy, for astrology. There are more prosaic, if no less improbable, pyramidologies: the Great Pyramid was a training centre in ancient mysteries, or an initiation centre, or a temple; it was built for protection against earthquakes, or as a repository for sacred objects, or a giant water pump. It was built by Iranians or Atlanteans, or by extraterrestrials who made it a marker for a landing pad, or just a monument. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- College Publishing House(Publisher)

Pyramids functioned as tombs for pharaohs. In Ancient Egypt, a pyramid was referred to as mer , literally place of ascendance. The Great Pyramid of Giza is the largest in Egypt and one of the largest in the world. The base is over thirteen acres in area. It is one of the Seven Wonders of the World, and the only one of the seven to survive into modern times. The Ancient Egyptians capped the peaks of their pyramids with gold and covered their faces with polished white limestone, although many of the stones used for the finishing purpose have fallen or been removed for use on other structures over the millennia. The Red Pyramid of Egypt (c.26th century BC), named for the light crimson hue of its exposed granite surfaces, is the third largest of Egyptian pyramids. Menkaure's Pyramid, likely dating to the same era, was constructed of limestone and granite blocks. The Great Pyramid of Giza (c. 2580 BC) contains a huge granite sarcophagus fashioned of Red ____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ____________________ Aswan Granite. The mostly ruined Black Pyramid dating from the reign of Amenemhat III once had a polished granite pyramidion or capstone, now on display in the main hall of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Other uses in Ancient Egypt, include columns, door lintels, sills, jambs, and wall and floor veneer. The ancient Egyptians had some of the first monumental stone building (such as in Sakkhara). How the Egyptians worked the solid granite is still a matter of debate. Dr. Patrick Hunt has postulated that the Egyptians used emery shown to have higher hardness on the Mohs scale. Regarding construction, of the various methods possibly used by builders, the lever moved and uplifted obelisks weighing more than 100 tons. Obelisks and pillars Obelisks were a prominent part of the architecture of the ancient Egyptians, who placed them in pairs at the entrances of temples. - eBook - ePub

Imhotep Today

Egyptianizing Architecture

- Jean-Marcel Humbert, Clifford Price(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

CHAPTER 2THE EGYPTIANIZING PYRAMID FROM THE 18TH TO THE 20TH CENTURY 1Jean-Marcel Humbert (translated by Daniel Antoine and Lawrence Stewart Owens)“From the top of these pyramids, forty centuries look down upon you …” Whether or not Bonaparte really uttered these words on the Giza plateau, the pyramids have aroused admiration and have fascinated travellers throughout history. Dominique Vivant Denon too was struck by their enormous size and purity of form when he first saw them at the beginning of Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign. In his works (Denon [1802] 1990), he describes better than anyone the impact they had:My soul was moved by the great spectacle of these great objects; I regretted seeing the night extend its veils over an image that dominates both eyes and imagination … The precision of the pyramids’ construction, the inalterability of their form and construction, and their immense dimensions, cannot be admired sufficiently. One could say that these gigantic monuments are the last link between the colossi of art and those of nature.A perfect shape with unusual powersEgyptian pyramids are certainly one of the most perfect and extraordinary shapes ever created by humans (Schadla-Hall and Morris 2003). The Giza examples are truly exceptional in terms of their enormous size – which makes them visible even from the moon! For five centuries, pyramids have influenced not only visitors to Egypt, but also those who have never seen them for themselves but have heard of them or seen poor reproductions (Humbert 1997b: 32–33). Bossuet (1681 quoted in Kérisel 1991: 8), whilst emphasizing the ostentation of Egyptian pyramids, admired their solidity, regularity, simplicity and ‘ordered’ yet bold design. Hegel (quoted in Kérisel 1991: 7) regarded the pyramid as being the building par excellence - eBook - ePub

Saving the Pyramids

Twenty First Century Engineering and Egypt's Ancient Monuments

- Peter James(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- University of Wales Press(Publisher)

From my perspective, reviewing the results and following the progression of the construction from the first to the last of the large pyramids, it appears that there must have been a moving spirit that linked the whole series of pyramid buildings. Starting at the Step Pyramid through to the final Great Pyramid, one can see the link between the design faults and the attempts to rectify the problems. I feel the highest admiration for these ancient builders for their innovation and skills in overcoming the difficulties and changing the way engineering problems were resolved.Consulting the vast array of archaeological information on all aspects of the building of these structures, some in great detail on the alignment, setting out, quarrying, transporting, and the theory of how they were constructed, each adding to what has been written before, I will not comment on these assumptions in detail because the cause and effect will become clear when the method of construction is analysed.Mankind’s rise out of the ground must start with the Step Pyramid. It has been acknowledged and confirmed by most authorities that this is the earliest large structure above the horizon. Dating back 4,700 years, it was at the cutting edge of building and civil engineering technology in ancient times.Unless we build a time machine capable of whisking us back all those centuries to examine the builders as they were constructing the pyramids, one can only guess at how these extraordinary structures were built by examining the evidence, both archaeological and structural, to determine methods and innovations required. We must approach the problem in the same manner as the great Sherlock Holmes, whose maxim was that if you remove all evidence that doesn’t fit the facts, then what’s left, must be the way it happened. What is not in doubt is that the pyramids still stand, and can be seen, and each tells us its own story. Even though, after all these centuries, they are no longer in their original state, their present condition provides us with an insight into their mode of failure.The Step Pyramid of Djoser, Saqqara.We have some knowledge of the problem, however partial and unreliable, from two ancient Greek historians. Herodotus, one of the earliest recorded travellers to be captivated by Egypt, visited the country in the fifth century bc, probably in the course of collecting material for his Histories , which provide the first known narrative of how the pyramids were built. Herodotus relied on an oral account, allegedly from a priest, but with very little in the way of technical information. The other source from antiquity is Diodorus Siculus’ Bibliotheca Historica - eBook - PDF

- George Rawlinson(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Gorgias Press(Publisher)

Fragments the deluge of old Time has left Behind in its subsidence—long long walls Of cities of their very names bereft,— Lone columns, remnants of majestic halls, Rich traceried chambers, where the night-dew falls,— All have I seen with feelings due, I trow, Yet not with such as these memorials Of the great unremembered, that can show The mass and shape they wore four thousand years ago. The Egyptian idea of a pyramid was that of a structure on a square base, with four inclining sides, each one of which should be an equilateral triangle, all meeting in a point at the top. The structure might be solid, and in that case might be either of hewn stone throughout, or consist of a mass of rubble merely held together by an external casing of stone ; or it might contain chambers and passages, in which case the employment of rubble was scarcely possible THE THREE PYRAMIDS OF GHIZEH. 67 It has been demonstrated by actual excavation, that all the great pyramids of Egypt were of the latter character—that they were built for the express pur-pose of containing chambers and passages, and of preserving those chambers and passages intact. They required, therefore, to be, and in most cases are, of a good construction throughout. There are from sixty to seventy pyramids in Egypt, chiefly in the neighbourhood of Memphis. Some of them are nearly perfect, some more or less in ruins, but most of them still preserving their ancient shape, when seen from afar. Two of them greatly exceed all the others in their dimensions, and are appropriately designated as the Great Pyramid and the Second Pyramid. A third in their immediate vicinity is of very inferior size, and scarcely deserves the pre-emin-ence which has been conceded to it by the designation of the Third Pyramid. Still, the three seem, all of them, to deserve descrip-tion, and to challenge a place in the story of Egypt, which has never yet been told without some account of the marvels of each of them. - eBook - ePub

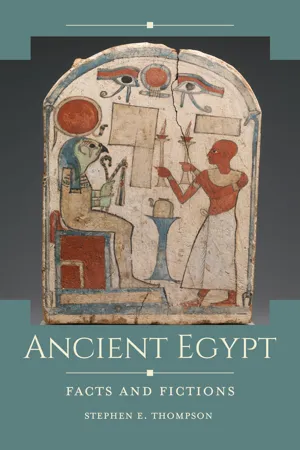

Ancient Egypt

Facts and Fictions

- Stephen E. Thompson(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

When the Greeks first arrived in large numbers in Egypt during the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, under the reign of Pharaoh Psammeticus I (664–525 BCE), they encountered a civilization that was already over two thousand years old. The Greeks were impressed with the great antiquity of Egypt, by the large and impressive monuments they observed, and by the hieroglyphic inscriptions they found covering the walls of tombs and temples. By the time the Greeks arrived, however, the great age of pyramid building in Egypt had long since passed. The last kings known to have built pyramids belonged to the Thirteenth Dynasty (1759–ca. 1630 BCE). By the time uniform rule over all of Egypt was restored in the New Kingdom, the pharaohs had adopted another method for their burials: the underground rock-cut tomb. Smaller pyramids continued to be built for the graves of wealthy private individuals.Scene from a mosaic in St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice, ca. 1275, showing Joseph overseeing the storing of grain in the pyramids. (Joseph Gathering Corn. Circa 1275. Mosaic at St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice.)With the passage of time, the original purpose of the pyramids was no longer operative; they had long since been robbed of their royal occupants, and the daily cult of offerings had ceased to function. When travelers visited the pyramids, and many did, they were awed by their size (the Great Pyramid at Giza was the world’s tallest man-made structure until well into the nineteenth century) and the amount of labor that must have been involved in their construction. The size of the Great Pyramid led some early Greek visitors to assume that the pyramid could only have been built by cruelly exploiting slaves, leading to the tradition of Khufu as a tyrant. Other early visitors saw the pyramids as evidence of the Egyptian rulers’ vainglory and selfishness.Some early Christians found a place and a meaning for the pyramids in the sacred history found in the Bible. The idea that the pyramids were built by the biblical Joseph to serve as granaries during the seven plentiful years to store up grain for the seven years of famine described in the Book of Genesis/Breshit first becomes evident during the fourth century. When Islamic rulers took control of Egypt in the seventh century, the pyramids entered into Muslim lore. Rather than seeing the pyramids as evidence of the Egyptian rulers’ pride and selfishness, the Muslim historian and philosopher Al-Baghdadi (1161–1231) saw them as evidence of “noble intellects” and “enlightened souls” who were possessed of considerable engineering skill (El-Daly 2005, 48). A major topic of discussion among Muslim scholars was whether the pyramids were built before or after the biblical flood, which Abu Ma ͑ shar, writing in the ninth century, dated to 3100 BCE (El-Daly 2005, 10). According to a legend that one scholar traces back to 840/41 CE, the pyramids were built before the flood to preserve Egyptian wealth and learning (Fodor 1970, 350). Long after the pyramids had ceased to fulfill their original purpose, those who encountered them attempted to explain them by recourse to their own conceptions of humankind and world history. That process continues unabated even now. - eBook - ePub

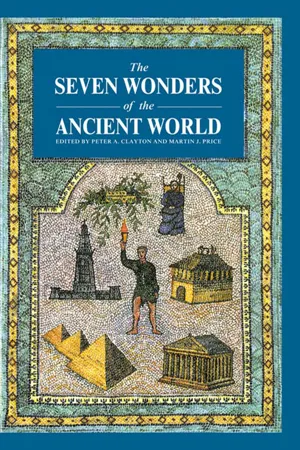

- Peter A Clayton, Martin Price, Peter Clayton(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1THE GREAT PYRAMID OF GIZA

PETER A. CLAYTONTHE PYRAMIDS of Egypt have always been listed from the beginning amongst the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but it is actually the Great Pyramid at Giza that is the focus of attention and takes its place at the head of the list. It is the only one of the Seven Wonders that still stands in an almost complete and recognisable form; it is also the oldest. Built for the pharaoh Khufu (or Cheops, as the Greek historian Manetho calls him) of the Fourth Dynasty, about 2560 BC, the pyramid represents the high water mark of pyramid building in Old Kingdom Egypt.The Greek priest/historian Manetho, who came from Sebennytus in the Delta of Egypt, wrote a history of Egypt during the reign of Ptolemy II (284–246 BC). In it he divided ancient Egyptian history into a series of thirty dynasties. These fell into three main sections – the Old Kingdom (First to Sixth Dynasties, c. 3100–2181 BC, although the first three dynasties are also referred to as the Archaic period); the Middle Kingdom (Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties, c. 2133–1786 BC), and the New Kingdom (Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties, c. 1567–1085 BC). These represented periods of central government stability (ma'at in ancient Egyptian, a goddess represented by the Feather of Truth who governed all things that the Egyptian relied upon – truth, stability, the never-changing cycle of life, etc.). In between these three major periods were times of instability with the breakdown of central government. They are known respectively as the First Intermediate Period (Seventh to Tenth Dynasties, c. 2181– c . 2133 BC), and the Second Intermediate Period (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Dynasties, c. 1786–1567 BC). It was during the latter period that Egypt first suffered domination by outside peoples, the Hyksos (the so-called ‘Shepherd Kings’) who came from the Syria/Palestine area and were finally expelled in the mid-sixteenth century BC by warlike princes of Thebes in Upper Egypt who founded the Eighteenth Dynasty and the New Kingdom. Egyptologists refer to the period after the Twentieth Dynasty either as the Third Intermediate Period or the Late Period (c. - eBook - ePub

- Peter A. Clayton, Martin J. Price, Peter A. Clayton, Martin J. Price(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1

THE GREAT PYRAMIDOF GIZA

PETER A. CLAYTON

THE PYRAMIDS of Egypt have always been listed from the beginning amongst the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but it is actually the Great Pyramid at Giza that is the focus of attention and takes its place at the head of the list. It is the only one of the Seven Wonders that still stands in an almost complete and recognisable form; it is also the oldest. Built for the pharaoh Khufu (or Cheops, as the Greek historian Manetho calls him) of the Fourth Dynasty, about 2560 BC, the pyramid represents the high water mark of pyramid building in Old Kingdom Egypt.The Greek priest/historian Manetho, who came from Sebennytus in the Delta of Egypt, wrote a history of Egypt during the reign of Ptolemy II (284–246 BC). In it he divided ancient Egyptian history into a series of thirty dynasties. These fell into three main sections — the Old Kingdom (First to Sixth Dynasties, c. 3100–2181 BC, although the first three dynasties are also referred to as the Archaic period); the Middle Kingdom (Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties, c. 2133–1786 BC), and the New Kingdom (Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties, c. 1567–1085 BC). These represented periods of central government stability (ma'at in ancient Egyptian, a goddess represented by the Feather of Truth who governed all things that the Egyptian relied upon — truth, stability, the never-changing cycle of life, etc.). In between these three major periods were times of instability with the breakdown of central government. They are known respectively as the First Intermediate Period (Seventh to Tenth Dynasties, c. 2181– c. 2133 BC), and the Second Intermediate Period (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Dynasties, c.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.