Technology & Engineering

Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China is a series of fortifications made of stone, brick, tamped earth, wood, and other materials, built along the northern borders of China to protect against invasions. It is one of the most impressive architectural feats in history and a testament to ancient engineering and construction techniques. The wall stretches over 13,000 miles and is a symbol of China's rich cultural heritage.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Great Wall of China"

- Aaron Millar(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Icon Books(Publisher)

ASIATHE Great Wall of ChinaThe Great Wall of China is a 13,000-mile network of walled fortifications that extends across the country’s northern territory. Built over two millennia by the hands of millions of workers, it is the longest man-made structure on the planet. But it is not a continuous wall, nor was it conceived as a singular vision. Rather the Great Wall, or Chángchéng, the Long Wall as it is known in China, is like the tributary of a river, a vast earth and stone snake with multiple arms and legs that stretches across the nation from Shanhaiguan in Hebei province in the east, to Jiayuguan in Gansu province in the west. That it is the only man-made structure that can be seen from space is a myth. Its natural building materials blend into the local topography making it, in fact, incredibly hard to discern, even from low Earth orbit. But the scale of it is nonetheless astonishing.The idea was originally conceived by the Emperor Qin Shi Huang in the 3rd century BC . Up until this point, China was composed of a number of separate, and often warring, kingdoms. As the first ruler of a unified China, Qin Shi Huang ordered that the scattered fortifications of these smaller provinces be joined together into a single continuous wall, which would protect the empire from Mongol and barbarian raiders to the north. This enormous barrier was known as the 10,000-Li-Long Wall (a li being a Chinese unit of distance equivalent to about a third of a mile) and would stretch from the Tibetan plateau in the west to the Pacific.Construction on the wall continued on and off through the centuries as emperors, and enemies, rose and fell. But it reached its peak during the Ming dynasty of 1368–1644. Despite the more than 1,500 years of previous effort, the Mongol hordes, under Genghis Khan and his son Kublai, managed to breach the Great Wall in the middle of the 13th century and subsequently ruled over China until 1368. After they were overthrown, in fear of another attack, the new Ming rulers ceaselessly strengthened and maintained the Great Wall for three centuries, expanding it to over 5,500 miles of continuous fortification. At its peak, more than a million soldiers were posted along its ramparts.- eBook - ePub

- Ai Jing, Gangliu Wang, Aimee Yiran Wang(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- WSPC(Publisher)

Using satellite remote sensing to survey the Great Wall is an advanced technology. China began using satellite remote sensing technology in the 80s. This fell under the aegis of the Center for Remote Sensing in the former State Department of Geology and Mineral Resources. It surveyed the parts of the Great Wall within Beijing's jurisdiction in 1986 to 1987 and the parts in the Ningxia area. Both surveys produced good results. The result of the satellite remote sensing survey shows that the wall in the Beijing area measures 629 kilometers in length, with 827 towers, 71 passes, and 8 camps. The wall in Ningxia measures 1,507 kilometers, with 706 towers, 1,065 platforms, and 282 fort camps. The margin of error is less than 1%. The intact wall and the parts which are in ruins are clearly distinguishable on the satellite infrared film.Based on satellite remote sensing technology, we found that the well-preserved and connected Great Wall in the Beijing area totals 123 kilometers, about 19.55% of the total length of the Great Wall. The well-preserved Great Wall in the Ningxia area measures 648 kilometers, about 42.99% of the entire wall. This technology's high-resolution images of the wall structure enable us to identify the chronological sequence of the construction. For instance, the ancient wall built before the Ming Dynasty is mostly along the Ming Great Wall. During the construction of the Ming Great Wall, some older walls were straightened (eg. in Shixia and Qing Shui Ding), some were abandoned and new sites were built (Guangtuo Mountain and Hezi Jian). The Ming Great Wall in Beijing area was primarily built and updated on the foundation from previous eras. Unfortunately, satellite remote sensing is unable to pinpoint the time when the older wall was built.2. Defining the Great Wall

What is the Great Wall? The Great Wall was an important military defensive construction in ancient China. Numerous records can be found in ancient Chinese texts. Important sites of the Great Wall from ancient China remain today, such as the Great Walls built in the States of Yan, Zhao, Qi, Qin by King Zhao, by Qin Shihuang, Han Dynasty, Ming Dynasty, etc. Their form and structure are clearly visible. They provide reliable sources for giving a definition for the Great Wall.This book attempts to define the Great Wall as such:“The Great Wall is a high wall fortified using earth, stones and bricks. It is an ancient military defensive construction for border protection.” We can also reorganize the definition as such:“The Great Wall is an ancient military defensive construction for border protection. It is a high wall constructed with earth, stones, and bricks.” - eBook - ePub

- (Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Lonely Planet(Publisher)

The Great Wall

Visiting the Wall

Mutianyu

Gbeiku

Jiankou

Zhuangdaoku

Jinshanlng

Huanghua Cheng

Badalng

The Great Wall

He who has not climbed the Great Wall is not a true man.Mao ZedongChina’s greatest engineering triumph and must-see sight, the Great Wall (万里长城; Wànlǐ Chángchéng) wriggles haphazardly from its scattered Manchurian remains in Liáoníng province to wind-scoured rubble in the Gobi desert and faint traces in the unforgiving sands of Xīnjiāng.The most renowned and robust examples of the Wall undulate majestically over the peaks and hills of Běijīng municipality, but the Great Wall can be realistically visited in many north China provinces. It is mistakenly assumed that the wall is one continuous entity; in reality, the edifice exists in chunks interspersed with natural defences (such as precipitous mountains) that had no need for further bastions.Best Places to Sleep

A Commune by the Great WallA Brickyard Eco RetreatA Great Wall Box HouseA Zǎoxiāng YardA Ténglóng HotelGreat Wall History

The Great Wall (长城; Chángchéng), one of the most iconic monuments on earth, stands as an awe-inspiring symbol of the grandeur of China’s ancient history. Dating back 2000-odd years, the Wall snakes its way through 17 provinces, principalities and autonomous regions. But nowhere is better than Běijīng for mounting your assault on this most famous of bastions.Official Chinese history likes to stress the unity of the Wall through the ages. In fact, there are at least four distinct Walls. Work on the ‘original’ was begun during the Qin dynasty (221–207 BC), when China was unified for the first time under Emperor Qin Shihuang. Hundreds of thousands of workers, many of them political prisoners, laboured for 10 years to construct it. An estimated 180 million cu metres of rammed earth was used to form the core of this Wall, and legend has it that the bones of dead workers were used as building materials too. - eBook - ePub

World Heritage Craze in China

Universal Discourse, National Culture, and Local Memory

- Haiming Yan(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Berghahn Books(Publisher)

1 . In spite of popular usage and acceptance of the term the “Great Wall” of China, the definition and historicity of the Great Wall is still a matter of scholarly debate. According to Arthur Waldron, popular narratives of the Great Wall are modern constructions and mistaken perceptions from the past few centuries. Literally and physically, the so-called Great Wall should be more precisely understood as an artificial conceptual construction related to a series of defensive fortifications, or “long walls” literally in Chinese (Waldron 1992). Likewise, Julia Lovell lays out three mythical narratives of the Great Wall: its singularity, cultural superiority, and military function (Lovell 2006: 15–17). Rather than a historic representation, the Great Wall is negatively characterized in Lovell’s analysis:Ever since walls were first built across Chinese frontiers, they have provided no more than a temporary advantage over determined raiders and pillagers. It was a sign of military weakness, diplomatic failure and political paralysis, and a bankrupting policy that led to the downfall of several once robust dynasties. (Lovell 2006: 17)2 . For more information about the Republican Revolution, see Worden, Savada, and Dolan 1987.3 . Two major battles took place: at Shanhaiguan in January 1933 and Jehol in March 1933. The Chinese troops even defended the wall “hand-to-hand,” whereas by the end of May 1933, after two months of battle, the Japanese controlled all the key northeast wall passes.4 . Also known as the Nanking Massacre, it was committed by Japanese troops on 13 December 1937.5 . One li is half a kilometer.6 . The film was not screened in the end.7 . http://badaling.cn/language/info_en.asp?id=45 .8 . Mentions of the Great Wall in the West were scarce before AD 1650. See Waldron (1992: 204–6) for more discussion.9 - eBook - PDF

Chinese Walls in Time and Space

A Multidisciplinary Perspective

- Roger Des Forges, Minglu Gao, Chiao-mei Liu, Haun Saussy, Roger Des Forges, Minglu Gao, Chiao-mei Liu, Haun Saussy, Thomas Burkman(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Cornell East Asia Series(Publisher)

They thus failed to dent—and may actually have reinforced—the image that most people in China and the rest of the world have long embraced and that apparently still influenced the thinking of major scholars in the field of Chinese history, of the wall as a single continuously existing structure, defining an unchanging border, and begun in ancient times. 6 After reading more in the primary and secondary sources, I be- came convinced that the concept of a Great Wall of China that had 2 Lattimore, Inner Asian Frontiers, pp. 21–25, 429–68, maps on p. 22 and 530. 3 Ibid., p. 21; Lattimore, Studies, pp. 101–5. 4 Needham, Science and Civilisation, IV.3, pp. 47, n.f.; 53. 5 Needham, Science and Civilisation, I, pp. 92, 100. Needham used his own Romanization for wanli changcheng, lit. “the 10,000 li-long wall,” a term that first appeared (as a metaphor) during the Liu Song dynasty (420–79 CE). Waldron, Great Wall, p. 202. 6 These scholars included my one-time colleagues Frederick Mote, Marius Jansen, James T. C. Liu, and Denis Twitchett, now all deceased, as well as Ying-shih Yu. The Great Wall of China 5 come down to us by the mid–twentieth century contained a great deal of myth. 7 Some writers on the wall were aware of the problems, and even pointed them out, but the myths proved well nigh unstoppable, at least at the popular level, in both China and the rest of the world. This was so much the case that the prominent Chinese journalist Liang Qichao took mistaken beliefs about the wall in the early twentieth as a prime example of historical misinterpretation in his influential book about historical method. 8 Given “the degree to which our understand- ing of Chinese history has been and is distorted by confusion about the Great Wall,” I decided to draft a paper to summarize the myths in one place. - Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

Archaeologies of Empire

Local Participants and Imperial Trajectories

- Anna L. Boozer, Bleda S. Düring, Bradley J. Parker, Anna L. Boozer, Bleda S. Düring, Bradley J. Parker(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

57 ChaPter three The Great Wall as Destination? Archaeology of Migration and Settlers under the Han Empire aLice yao Borders and Settlers Border security remains a presiding concern of empires past and present, with the Great Wall of China representing one of most iconic and enduring examples of a geopolitical barrier. While the geographic scale of the wall continues to excite imaginations, including recently that of President Donald Trump and his vision for the United States-Mexico border, scholars of China have long debated its actual impermeability as a barrier in dynastic history (Phillips 2017). Far from being the creation of one person’s vision, the Great Wall owes its existence to the Qin (221–207 BCE), whose ambitions of unifying classical states took on the project of linking disparate wall sections built by vanquished states. The expansion of the wall—roughly eight thousand kilometers, from modern-day North Korea to the Tarim Basin—was realized by the successor Han Empire (206 BCE–220 CE), which conquered a vast geographic expanse rivaling that of contemporary Rome. While a line of wall often marks the political boundary of the Han Empire on maps, the contiguity of this barrier in space has been the subject of much debate. Archaeologically, the Han wall is visible, but only in sections (Figure 3.1), thus opening to discussion its status as a geopolitical barrier (Lattimore 1988). Instead of the wall functioning to keep nomads from raiding the Han interior, scholars now contend that the structure was expanded to enclose new imperial territories and to keep Han migrants on the frontier from running away from state and tax obligations (Waldron 1992; Di Cosmo 2002). A third view even conjectures that far from an organic whole, the wall was less a boundary than a provisional front that moved with the military (Chang 2007). Although these - eBook - PDF

Do Good Fences Make Good Neighbors?

What History Teaches Us about Strategic Barriers and International Security

- Brent L. Sterling(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Georgetown University Press(Publisher)

Conclusion Most of Yu’s original barrier has vanished, and the remainder only provides mod-est cover from the area’s worsening sandstorms. By contrast, visiting the Great Wall at Simatai, northeast of Beijing, with its 70-degree slope up 2,500-foot peaks, leaves one awestruck. A stop at this place or another section near the capital has become obligatory for any first-time visitor. It has been estimated that one-third of the Ming Great Wall is still in fairly good condition with an-other third remaining in poor shape. Construction of the barrier has actually begun again in recent decades, reaching about twenty miles according to one recent study. 231 Now, however, this work is done to lure tourists rather than repel raiders. Many of the sightseers are Chinese, who in the past century have come to view the Great Wall as a source of pride and accomplishment. For Chinese and foreigners alike, the barrier stands as the most famous symbol of the Middle Kingdom. Does this fond memory accurately reflect the Ming Great Wall of China’s contribution to Chinese security? Given that “the Ming experienced more at-tacks over a longer period than any other Chinese dynasty,” such fortifications had been regarded as essential by government offi cials. 232 At the same time, the existence of such attacks undermines claims of its value as a strategic deterrent. Most historians characterize the structure as unsuccessful. 233 Mote typifies this view by concluding that “China’s Great Wall wasted vast amounts of treasure and it defined a foreign policy that was shortsighted and doomed to failure.” 234 The high military expenditures not only failed to tame external challenges but also contributed significantly to the emergence of an internal climate that finally brought down the dynasty. Instead scholars generally regard the ignored ap-proach of accommodation as offering the best chance for stability and prosper-ity along the northern frontier. - eBook - PDF

- (Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Alma Classics(Publisher)

253 The Great Wall of China T he most northerly pArt of the Great Wall of China has been completed. It is there that the sections leading from the south-east and south-west finally merge. This system of piecemeal construction was also used at a lower level, in the two vast armies of workers, the eastern army and the western army. This is how it was done: groups of about twenty men each had to construct a five-hundred-metre or so stretch of wall, while a neighbouring group built another stretch of the same length that joined up with it. But once the merger was complete, instead of continuing construction at either end of this thousand-metre stretch, the groups of workers were sent off to build the wall in a completely different place. As a result there were many large gaps that were slowly filled in, although in some cases only after it had been announced that the wall was finished. In fact there are appar-ently gaps that have never been filled in, some of them longer than the sections that were actually built, although, given the length and extent of the edifice, this claim, which is just one of the many myths that have grown up around the building of the wall, is impossible to verify or measure, at least for an individual person. This being the case, one would have thought that it would have been a better idea from every point of view to build it all in one go from the outset, or at least to construct the two main sections in one go. Because the wall, as is well known almost everywhere, was designed as a defence against the peoples from the north. But 254 the metAmorphosis And other stories how can a wall protect anything if it isn’t built all at once? In fact not only can such a wall not protect anything, the construction itself is in constant danger. - eBook - PDF

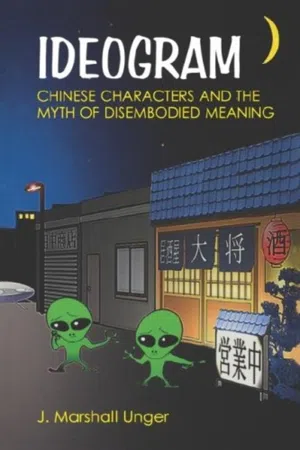

Ideogram

Chinese Characters and the Myth of Disembodied Meaning

- J. Marshall Unger(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- University of Hawaii Press(Publisher)

3 The Great Wall of China and other exotic fables As I mentioned in Chapter 1, Gaspar da Cruz was probably the first European to come up with the contagious idea that Chinese characters are hieroglyphic-like ideograms. Many others more famous, like Matteo Ricci, abetted him, but it is fitting that John DeFrancis zeroed in on da Cruz—for it was also he who initiated the Western legend of the Great Wall of China. The Great Wall, so the story goes, was built in ancient times by a corvée labor force of unimaginable size. It stretched from the sea to the interior deserts of western Gansu, blocking the northern entry into the fabled land of silk. No architectural project in antiquity, we are assured, equaled the size or cost of the Great Wall. The pyramids of Egypt, the Roman roads and aqueducts, were stupendous achievements, yet only the Great Wall, among all human buildings, is so vast that an astronaut standing on the Moon can see it with the naked eye (weather on Earth permitting, of course). After all, it’s right there in one of the Believe It or Not cartoons of Robert Ripley (a famous lover of Chinese women if not China itself ). But why cavil? Has not the Great Wall fueled the imagina-tions of writers down to Kafka? Is it not, thanks to the propaganda appa-ratus of the Chinese Communist Party, the very symbol of the Chinese nation? THE HANDWRITING’S ON THE WALL Despite the ubiquity of the Great Wall idea throughout the literate world, it is almost impossible to find a reference to it in Chinese literature prior to the Ming dynasty. It was during that isolationist period of late im-perial Chinese history that most of the structure now called the Great Wall was constructed. Though some of that construction was new, much of it simply linked together preexisting fortifications and towers scattered here and there across Inner Mongolia, an area that had for centuries wit-40

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.