History

Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo was a powerful state located in west-central Africa during the 14th to 19th centuries. It was known for its sophisticated political structure, trade networks, and the early adoption of Christianity. The kingdom's economy was based on agriculture, mining, and trade, and it played a significant role in the transatlantic slave trade.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Kingdom of Kongo"

- eBook - ePub

- John Parker, David Adjaye(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Thames and Hudson Ltd(Publisher)

6 Yet Kongo’s wealth of written and oral sources have raised complex problems of interpretation, for example as its historians have sought to understand and to reach beyond Afonso’s efforts to recast the past and to shape the future. How and what can we know, then, of the kingdom over which Afonso and his brother fought in 1506?KONGO BEFORE 1500

The origins and early history of Kongo have been the subject of much debate. One point of contention has been the narrative of Lukeni lua Nimi’s founding of the kingdom, a process that historians tend to date to some point in the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century. This is a debate that extends beyond the region and even beyond Africa, as at its core is the issue of the relationship between ‘myth’ and ‘history’. Kongo was one of many Bantu-speaking kingdoms in Central Africa of which the traditions of origin turned on the arrival of a noble stranger from across a river, who seizes power from an older, often despotic, dynasty and inaugurates a new civilized social order based on sacred kingship. Vansina’s pioneering efforts to mobilize these accounts tended to take them quite literally, assuming that culture heroes like Lukeni lua Nimi, Kalala Ilunga of the Luba and Cibinda Ilunga of the Lunda were historic state-builders whose conquests could be dated by counting the generations of remembered kings back from verifiable successors.7 Subsequent interpretations, however, rejected the idea that these were historical figures. The anthropologist Luc de Heusch, most prominently, argued that traditions of origin were mythical charters, albeit ones with profound and deeply rooted meanings for local societies.8 - eBook - PDF

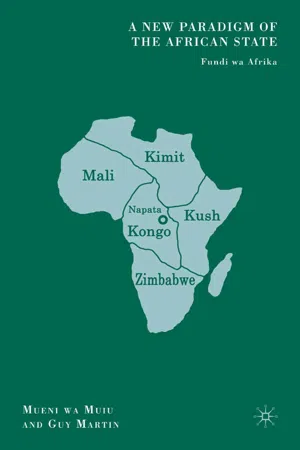

A New Paradigm of the African State

Fundi wa Afrika

- M. Muiu, G. Martin(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Kongo remained the undisputed leader among the coastal states of Central Africa up until the end of the sixteenth century, when its supremacy was challenged by its neighbors and the Portuguese colony of Angola, founded in 1548. The Kongo kingdom was highly centralized—it was structured around a tightly controlled core, and distant, relatively autonomous regions where cen- tral power and authority was far weaker, in the periphery. The basic unit of the political system was the village, which, in turn, was made up of tightly knit, extended matrilineal families known as kanda. The kanda (or clan) consisted of the descendants of a common ancestor connected to each other by blood. Women of free status were the pillars of the Kongo family, and, by virtue of their social status, only they could confer membership in the kanda. Within each kanda, power, wealth, and privilege were based on seniority and were usually passed by the male head of the kanda to his nephews, the sons of his sisters. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was also common for women to be heads of kanda. Princes and kings were always born within a royal kanda, inheriting their rank through their mothers. In the late sixteenth century, the kingdom included about five million subjects and was divided into six main provinces: Soyo, Mpemba, Mbamba, Mpangu, Mbata, and Nsundi. 3 Each district or province was headed by a governor, who commanded broad military, fiscal, and administrative powers conferred by the king. The Congo State in Historical Perspective I 105 All the titleholders bore the title of mani, followed by the name of their district or province. In the case of officials at the royal court, the title mani was followed by the name of their specialized function, for example, the mani lumbu (governor of the king’s quarters in the capital); mani vangu vangu (first judge and special- ist in cases of adultery); and so on. - Barbaro Martinez-Ruiz(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Temple University Press(Publisher)

19 At its height in the fifteenth and sixteenth centu-ries, the Kongo kingdom spanned territory from Gabon to Zambia. In ad-dition to this swath of direct control, the Bakongo had influence over, and economic relations with, the Ndumbu, Zombo, Yaka, Kuba, Lunda, and Luba kingdoms to the north, east, and south. 20 The Kongo kingdom was 19 The Atlantic Passage organized through a centralized government seated in the capital city of Mbanza Kongo (São Salvador) and benefited from the economic stability engendered by a kingdom-wide shell-based currency and the proliferation of trade routes along the Congo River to the interior and to Malembo, the settlement that became present-day Kinshasa. 21 Three important moments in the history of the Kongo kingdom led to its decline and ultimate decima-tion: first, the encounter with the Portuguese in 1482; second, the military conflict between the Portuguese and the Bakongo in 1665 and the defeat of the Bakongo at the battle of Ambouila; and, finally, the resulting rapid de-cline of the Bakongo state that culminated in the ceding of full control to Portugal during the scramble for Africa in 1884–1885. The Kongo kingdom’s fi rst contact with Europeans was in 1482 when Diego Cão arrived at the mouth of the Zaire (Congo) River with a Portu-guese exploration team. This initial contact was followed by the arrival of subsequent European exploration teams that were documented in travel-ogues, such as those published by Giovanni Antonio da Montecuccolo Cavazzi. It was through these early contacts that information about Ba-kongo culture fi rst became available to Europeans. On his return from his fi rst trip to the Kongo kingdom between 1482 and 1484, Diego Cão brought four Bakongo individuals with him to Portugal. Among them was a member of the noble class named Nsaku, who became the fi rst source of information about daily life in the Kongo kingdom and is mentioned fre-quently in accounts written at the time.- eBook - PDF

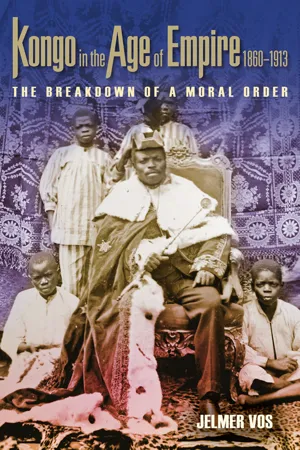

Kongo in the Age of Empire, 1860–1913

The Breakdown of a Moral Order

- Jelmer Vos(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

19 1 The Kingdom of Kongo after the Slave Trade Modern-day views of the Kingdom of Kongo as a once powerful state that had all but vanished on the eve of colonial rule have their roots in the published observations of nineteenth-century visitors to Kongo, who expected to find a great king where there was none. The writings of these missionaries, colonial officials, and other travelers still hold important clues about the nature of royal power in Kongo in the late nineteenth century, although they present a confus- ing picture of the kingdom. These European visitors often expressed ambivalent views of the Kongo polity, resulting from a conflict between their everyday expe- riences and their Eurocentric notions of kingdoms as centralized states and kings as autocrats. Missionaries, for instance, could trivialize the authority of the king of Kongo and at the same time describe lesser chiefs as the king’s “vassals.” 1 They usually failed to understand the spiritual dimension of royal power, and therefore also failed to connect the ubiquity of Roman Catholic symbols in Kongo life to São Salvador as the kingdom’s sacred capital. Thus, after first vividly describing the enduring importance of crucifixes in the manage- ment of political and commercial affairs throughout Kongo around 1900, and pointing out that resentment among one clan over the usurpation of the Kongo throne by another had barely withered, the Baptist missionary Thomas Lewis stated that the kingdom had “been reduced to all but an empty name, for the present king of Kongo is nothing more than an ordinary chief, with very limited powers, even over his own people.” 2 Some Portuguese officials in Luanda believed that King Dom Pedro V (1860–91) was politically sovereign over the lands between the river Congo and Portugal’s own nominal possessions in Angola, a belief occasionally shared by 20 The Kingdom of Kongo after the Slave Trade European coastal traders. - eBook - PDF

The Democratic Republic of Congo

Between Hope and Despair

- Michael Deibert(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Zed Books(Publisher)

1 | Kingdom of Kongo TO FIRST CONGO REPUBLIC Despite its present image as a place of endless war, the people occupying the area that today comprises the nation of Congo were members of a myriad state-like entities that governed their various realms, sometimes for centuries, with varying degrees of sophistication and competence. These empires and statelets extended over 2.3 million square miles, of which some 60 per cent consisted of jungle cover. The mighty Congo River cut through the expanse, flowing 2,700 miles (4,344 kilometres) from its headwaters to the estuary, and spanning some 7 miles across at its widest point. Buffalo, cheetahs, elephants, leopards, lions, rhinoceros and zebras roamed its savannahs and mountain gorillas clung to the slopes of its densely forested mountains. Spreading eastward from the Atlantic Ocean and encompassing parts of present-day Angola, Congo-Brazzaville and Gabon as well as Congo itself, the Kingdom of Kongo was the dominant coastal kingdom in central Africa from roughly 1482 until 1550. 1 Its political structure was centred around M’banza-Kongo, where the king (Mwene Kongo or ‘Lord of Congo’) resided and around which the gravitational pull of central power revolved for the sur-rounding provinces. Kongo had an extraordinarily strong central state, with provinces ruled by governors appointed by the king, 2 and a shield-bearing infantry supported by thousands of lightly armed troops. 3 At some point in 1482 or 1483, the Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão came ashore from the Atlantic near the mouth of the Congo River, initiating the first recorded contact between Europeans 10 | one and the Bakongo people, several of whom Cão promptly seized as hostages and took back to Portugal. - eBook - PDF

- Joseph K. Adjaye(Author)

- 1994(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

One of the largest and most powerful of these states was Kongo, which expanded from its Angolan base to the 2 18 TIME IN THE BLACK EXPERIENCE area of modem Zaire and the Congo Republic. Other Bantu kingdoms that were created in the Congo river region included Bemba, Lunda, Lulua, and Kuba. By far, the most successful of the Bantu states of West Central Africa was Kongo, which developed a highly advanced iron technology, agrar- ian culture, complex trade systems, and elaborate political institutions well before the arrival of the first Europeans in the region in the late fif- teenth century. The high level of material culture attained by the Kongo state by the sixteenth century has been commented upon in both oral chronicles and documentary evidence. In the view of one commentator, "in terms of natural resources [Western Europe was] poorer and in terms of its economic development at the time, in many respects more back- ward than advanced" (Baran 1961, p. 138). However, the glory of the Kongo state did not last long after the European arrival, which signalled the beginning of its decline and ulti- mate demise. With the European entry almost simultaneously into the Americas and the establishment there of slave-based plantation systems, the fate of Kongo and that of the "New World" became intertwined for the next several centuries. Kongo, along with the other states of West Central Africa, became the region in all of Africa where Europeans obtained the most slaves that were transported across the Atlantic to labor on American plantations during the 3.5 centuries of slave trading from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. Also, it was Portuguese slave raiding activities that, more than any single factor, accounted for the destabilization and eventual fall of Kongo, politically and economi- cally. At the same time, European missionary activities, under the guise of civilizing the Kongo people, were slowly increasing European penetra- tion of the region. - eBook - PDF

Soundings in Atlantic History

Latent Structures and Intellectual Currents, 1500–1830

- Bernard Bailyn, Patricia L. Denault, Bernard Bailyn, Patricia L. Denault, Patricia L Denault(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

The combination of ancient royalty and Christianity made the Kongo state unusual in Atlantic Africa. 8 The two themes persisted, albeit reinter-preted, even when civil wars caused the virtual collapse of the state and even when the kingdom being fought over was more symbolic than real. Ordinary Kongos accepted the idea of royalty and strove to have a Christian identity. 9 The Kongo state reached the apogee of its centralization during the reign of King Álvaro I (1568–1578) and his successors until the reign of King António I (1661–1665). Álvaro pushed to intensify and strengthen Christianity throughout the kingdom. He wanted Kongo to be like the Kongo and Dahomey, 1660–1815 89 Christian monarchies in Europe, and he successfully petitioned the pa-pacy to have the kingdom declared an episcopal see in 1596, requested and had sent from Rome many relics and other Catholic paraphernalia, and changed the name of his capital to São Salvador from its Kikongo name Mbanza Kongo. He and his son Álvaro II also introduced such European titles as duke, count, and marquis for the nobility who were appointed to various offices in the kingdom. The kings insisted that they be treated with the same courtesy and ceremony as European monarchs received from their subjects, visitors, and foreign residents or religious personnel. The size of the kingdom and the rituals that embodied king-ship during the period informed the conception of the state and the identity of future generations of Kongos. These ideas rested on the no-tion of a large and powerful kingdom, a king who exercised a range of functions, well-developed notions of royalty, and the central role of the Christian religion in the functioning of the state. Kongo kings always publicly claimed that they ruled over extensive lands (Map 2.1). - eBook - PDF

The Kongo Kingdom

The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity

- Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

123 1 2 3 5 The Eastern Border of the Kongo Kingdom: On Relocating the Hydronym Barbela Igor Matonda Introduction The KongoKing project focused on the origins and the early his- tory of the Kongo kingdom. Its aim was to examine how political centralisation and economic integration within the realm of that polity influenced language evolution and how these macro-historical processes are reflected in the archaeological record. Within this ambi- tious endeavour, it has been key to define what we understand by the concept of ‘Kongo kingdom’. Such an attempt at circumscribing the project’s core topic entails several questions, which are easier to ask than to answer, definitely when it comes to pinning down its evolving borders, not only in space and time, but also in the mind of its (poten- tial) subjects. A kingdom is never only a geographical territory under the direct political, economic and/or military control of the central authorities, but it is also a symbol of identity and belonging to which people may adhere, even far beyond the scope of the king’s territorial dominion. Whatever the concept ‘border’ may mean in each particular case, the borders of a kingdom need to be identified and explained historically (Storey 2001; Fray and Perol 2004). Chapters 1 and 4, by John Thornton, and Chapter 2, by Wyatt MacGaffey, broach the issue of the Kongo kingdom’s borders and the limits of the political influence of its leaders through very different methodological lenses. It is evident that in spatial terms the Kongo kingdom was not a static and fixed entity; its size and form changed considerably over time according to the fluctuating alliances and conquests that occurred. For the KongoKing project, the location of boundaries and the identification of Kongo centres of political power known as mbanza were of particular relevance in view of the archaeological excavations undertaken. - eBook - ePub

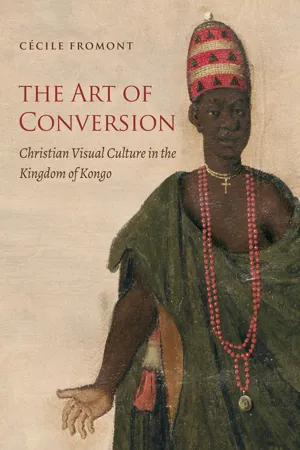

The Art of Conversion

Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo

- Cécile Fromont(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Omohundro Institute and UNC Press(Publisher)

The idea of fetishism, which would eventually become the prominent European descriptive and analytical term for African culture in the nineteenth century, encapsulated the perceived inability of the inhabitants of the region to produce elaborate forms of social organization, conduct rational economic transactions, or develop sophisticated religions. If European accounts of the Kongo could be very stark and critical, the objections they raised were not those encompassed by the newly developed term fetishism. Far from these prejudiced views, the numerous descriptions of the Kongo as an eminent realm of ancient wisdom testify to the success of Afonso’s cross-cultural invention. 25 Iron Kingdom and Iron King The Kongo Christian discourse that Afonso created functioned equally well in both European and African contexts owing in large part to the two visual and symbolic hinges that anchored it: the motif of iron and the image of the cross. Kongo myths of creation recorded in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries associated the foundation of the kingdom with the arrival of a civilizing hero and founding king who brought with him knowledge of iron technology. Since ironworking had been practiced in the region for at least several centuries before the emergence of the kingdom, the association was not grounded in historical fact; rather, it reflected the fundamental significance of the link between kingship and the metal in the political worldview that the myths expressed. The mythical and ritual pairing of iron and leadership is a shared feature of many central African polities both in the past as well as in recent times. Twentieth-century Bakongo consultants from the region that once formed the core of the Kongo kingdom expressed the connection with the term ngangula a kongo, or “smith of the Kongo,” which they used as a royal title - Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba, Toyin Falola, Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba, Toyin Falola(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

48The Luba kingdom of West Central Africa had emerged by about 1500, and according to oral traditions achieved its political structure during the reign of Kalala Ilungu who overthrew his uncle, the purported founding king Kongolo. The Luba king held absolute authority over subordinate chiefs and titleholders. The basic administrative structure of the kingdom was hierarchical and rested on lineage -based homesteads, villages under headmen, chiefdoms each under a territorial chief (kilolo ), and provinces. The central government comprised the king and titleholders; territorial and provincial chiefs had titles, as did counselors and officials at the capital, such as the war leader, the head of the officer corps , and the keeper of the sacred emblems. Usually titleholders were relatives of the king, and when the king died they were replaced by relatives of the new king . The only legitimate claimants to the kingship were those who were believed to have a sacred quality, bulopwe , believed to be vested in the blood and transmissible only through males. Bulopwe gave kings the right and the supernatural means to rule; all bulopwe stemmed from Kongolo or Kalala Ilunga, hence the king ruled by divine right and had supernatural powers, and challenges to the king could only come from other descendants from these two rulers . The organization of the kingdom was perpetuated by two devices: perpetual succession and positional kinship. Each successor to any given office took the title and name of the original holder of the office, hence all rulers had the same name even though they were not necessarily father and son; anyone who took over a position also took the earlier titleholder’s name, even if they were unrelated. If the original titleholder was a relative of another titleholder, then that relationship between the two positions became permanent in a fictitious relationship. The relations between different offices were made permanent based on fictional, positional kinship. Earth priests were usually the head of the original family lineage which founded their village, and because of this connection with the ancestral founders they had highly respected religious powers. The priests had the authority to regulate land use and they allocated land for settlement indirectly by supervising lineage heads, who regulated access to hunting land , fishing streams, and fruit trees in the forest. Sometimes the priests took on direct political roles of leadership; usually, however, they worked with a chief who needed the earth priest’s approval in order to have legitimacy in the eyes of the people. The chief would recognize the powers of the earth priest through gifts and tribute , and political rituals such as the investiture of a new chief involved sacred symbols and the participation of the priest.49

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.