History

Post Classical Africa

Post Classical Africa refers to the period from around 1000 to 1500 CE, characterized by the rise of powerful empires such as Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. This era saw significant developments in trade, agriculture, and the spread of Islam, contributing to the growth of urban centers and cultural exchange. It was a time of flourishing civilizations and diverse political and economic systems across the African continent.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

5 Key excerpts on "Post Classical Africa"

- eBook - PDF

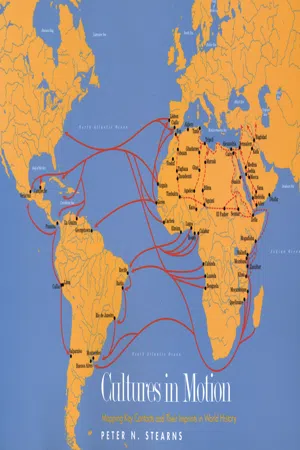

Cultures in Motion

Mapping Key Contacts and Their Imprints in World History

- Peter N. Stearns(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

Part II Postclassical and Early Modern Periods, 450–1750 CE The great classical empires fell or readjusted between 200 and 500 CE. Unity in the Mediterranean was shattered permanently with the collapse of Rome; China went through a long period of political disor-der; India returned to more regional political patterns with the end of the Gupta empire. These developments set the stage for a new wave of cultural contacts. Precisely because political arrangements began to misfire, people were open to new belief systems, particularly through religion, that would provide different kinds of assurances. Revision of political boundaries also opened the way for new travels by merchants, missionaries, and migrant peoples. The postclassical period (450–1450) saw the establishment of much more regular trading contact between Asia, Africa, and Europe. The principal routes ran east–west, from China and southeast Asia to the Middle East and East Africa, and from the Middle East to Europe. But subsidiary routes connected sub-Saharan Africa with the Middle East, both northwestern and northeastern Europe with the Middle East and Africa, and Japan with China. This intricate network obviously accel-erated cultural exchange. The new religion of Islam was most elabo-rately involved in this process, as both a cause and a consequence of expanded patterns of contact, but there were other results as well. The spread of world religions, launched earlier, accelerated, establish-ing much of the new framework for world history in the postclassical centuries. Chapters 3 and 5 outlined ongoing contacts resulting from Christianity and Buddhism. The development of Islam, beginning in about 600 CE, added a tremendous spur to cultural outreach, as this religion outpaced all others for several centuries. - eBook - ePub

- Mark S. Johnson, Peter N. Stearns(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Part II The Postclassical Centuries

DOI: 10.4324/9781315817354-6The postclassical centuries, following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West and the Han dynasty in China, were defined by a complex combination of continuity and change. Key features of the Roman Empire and classical Mediterranean civilization were carried forward in the Byzantine Empire, while the imperial and Confucian tradition revived strongly in China. Hinduism consolidated its hold in much of India. But major missionary religions expanded their territories and gained a greater role in several societies – and this included the new religion of Islam, founded shortly after 600 CE. Trade expanded, with new commercial links among key parts of Asia, Europe and Africa. And new civilization centers emerged in Northern Europe, West Africa, Japan and the Americas.Educational developments in the centuries after the fall of the great classical empires, from about 500 CE to about 1450 CE, reflect a similar combination of established features and major innovations. As some societies recovered from the collapse of the empires, leaders often sought to restore school systems that had worked well in the past: this was most obviously true in China, but it also applied to the Byzantine Empire and to India. Restoration often extended some of the classical achievements in new ways, as in the more formal implementation of examinations in China, but they built on a solid base.But the postclassical centuries also introduced the three significant changes that greatly altered the framework of the classical era and directly affected education. In the first place, the role of organized religion in schooling surged forward once again (though in India and also in Judaism this built on established traditions). The new religion of Islam, rising and rapidly expanding after 600 CE, particularly contributed to educational development, but Christian schools gained additional importance as well. The expansion of Buddhism affected education too, particularly in East Asia. In several regions, religion furthered a striking surge in advanced educational institutions. Schooling and religion had been linked before of course, in the need to train religious officials (as with Hinduism). Now, however, religious motivations expanded, to fill growing ranks of priests and imams but also to satisfy the needs of many students to expand their understanding. - eBook - ePub

A History of Science

From Agriculture to Artificial Intelligence

- Mary Cruse(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Arcturus(Publisher)

PART TWOTHE POST-CLASSICAL ERA

5TH–15TH CENTURIESTHE POST-CLASSICAL ERA – which roughly corresponds to the Middle Ages – is often thought of as a dark time in human history, a time when science gave way to ignorance and superstition. There is some truth in this; after the decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, scientific progress slowed and much knowledge was lost. But this period also saw genuine scientific innovation and advancement. This was particularly true in the Islamic world – here, classical scientific knowledge from Greece and Rome was preserved and eventually transported to Western Europe through booming trade networks and war. In Song dynasty China, a spike in industry coincided with a spate of groundbreaking engineering projects and inventions, including moveable type printing, gunpowder and paper money.Scientific endeavour in Eurasia was set back by the outbreak of the Black Death in the 14th century – a fearsome pandemic which killed millions of people and decimated the populations of Europe and the Middle East. But the end of the post-classical period saw an upsurge in cultural activity, culminating in the European Renaissance from the 15th century. To dismiss the post-classical era as a quiet, backwards period between two eras of enlightenment is to overlook the many scientific and technological advancements made during this portion of human history. Far from its characterisation as a ‘dark age’, the post-classical era saw thinkers and innovators continue the pursuit of scientific truth and enlightenment.Passage contains an image

CHAPTER 4 GEOGRAPHY

‘Geography is an earthly subject, but a heavenly science.’ – EDMUND BURKE, IRISH POLITICIAN AND PHILOSOPHERGeography – which translates from the Greek for ‘earth description’ – is the study of places, their physical features and the interactions between people and the environment. Although the word originates in Ancient Greece, people have been practising geography in some form all over the world for centuries. Geography flourished in Ancient Greece, but it became its own profession in Ancient Rome. In the post-classical era, the study of geography made great strides in the Islamic world, supported by Middle Eastern scholars’ profound knowledge of mathematics, eventually returning to Europe during the Renaissance. These events set the stage for the great explosion in geographic study that took place in the 18th and 19th centuries. - eBook - ePub

- Vincent Khapoya, Vincent B. Khapoya(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 4 ). Beginning in most African regions around 1880, and lasting in many regions beyond 1960, the colonial period interrupted the political life of Africans as never before; they were effectively removed from international political history, divested of domestic political power, and substantially excluded from colonial decision making.Despite the systematic removal of Africans from any substantive decision-making power during European colonial rule (c . 1900–1960), and despite the persistent conflicts and crises that have continued to impede African development since colonial times (c . 1960–present), historic Africa occupies a central position in our world. Africa has been called the most central of all continents geographically, with the majority of its landmass and population concentrated in the tropics (immediately north and south of the equator) and its Great Rift Valley being the earth’s most visible topographical feature (when viewed from the moon). East Africa’s Great Rift Valley has provided more opportunities for modern archaeologists to dig deeper into the early development of human beings than any other place. Since most of the documented prehistory of humankind took place in or near the Great Rift Valley, many scholars have argued that Africa was the original home of our earliest human ancestors. It is widely recognized that ancient Egypt (in the northern part of Africa’s Nile River Valley) developed the world’s earliest grand-scale civilization. It is also known that medieval African empires supplied large exports of gold to medieval Eurasian civilizations. African history, so central to the early development of human beings, ancient civilizations, and medieval commerce in our world’s history, has nonetheless been disregarded in Eurocentric studies. As late as the 1960s, a renowned British historian even maintained that Africa had no history. By that time, however, new kinds of historical techniques and data made it possible for Africans and Africanists (affiliated with new universities in independent African nations) to seriously begin reclaiming the rich African past. Historians like J. A. Rogers, Cheikh Anta Diop, and Basil Davidson had already begun to reassert the primacy of African civilizations in the ancient world by 1960. Around that time, archaeological reports from Louis and Mary Leakey hypothesized that the prehistoric ancestors of all human beings first evolved in the Great Rift Valley; linguists following Joseph Greenberg and Malcolm Guthrie developed techniques for indicating ancient historical connections between different African language families; and historians after Jan Vansina developed increasingly rigorous techniques for collecting, transcribing, and evaluating different kinds of oral traditions from medieval African kingdoms. D. T. Niane’s Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali and J. A. Egharevba’s Short History of Benin - eBook - PDF

The Precolonial State in West Africa

Building Power in Dahomey

- J. Cameron Monroe(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 1 INTRODUCTION As with all cultures, that of Dahomey is the product of its historic past; hence the more this past can be recovered, the greater the insight with which its civi- lization today can be studied. (Herskovits 1938: 4) W est Africa in the Atlantic Era (The Sixteenth Through nineteenth centuries AD) rests uncomfortably at a point of articu- lation in scholarly debates on the origins of social complexity and the state. A bewildering diversity of societies developed during this period, from expansive centralized states and empires, through smaller-scale segmentary line- age societies, whose survival rested on complex relationships with neighboring polities and European mercantile interests along the coast (Figure 1.1). Given the historical richness of the period, and unbroken cultural continuity into the twentieth century, West African kingdoms that emerged during the Atlantic Era figured prominently in scholarly discussions of non-Western political dynam- ics for much of the twentieth century (Forde & Kaberry 1967; Herskovits 1938; Law 1977b; McCaskie 1995; Smith 1969; Wilks 1975). Until the past few decades, however, scholars commonly downplayed the local underpinnings of West African polities, attributing the rise of the first cities and states across the region to the arrival of conquerors and traders from distant shores (cf. Levtzion 1973). The precolonial state in West Africa was thus viewed largely as “a super- structure erected over village communities of peasant cultivators rather than a society which has grown naturally out of them” (Oliver & Fage 1962: 47), defined in terms of markers of civilization introduced from elsewhere (Connah 2001; Mitchell 2005).

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.