History

British Industrial Revolution

The British Industrial Revolution was a period of significant technological, economic, and social change in Britain during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It marked the transition from an agrarian and handicraft-based economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacturing. Key innovations such as the steam engine, textile machinery, and iron production processes fueled this transformation, leading to urbanization and the rise of capitalism.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "British Industrial Revolution"

- eBook - PDF

- Frank W. Thackeray, John E. Findling, Frank W. Thackeray, John E. Findling(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

1 The Industrial Revolution, c. 1750-c, 1850 INTRODUCTION The word revolution often conjures up images of mobs roving the streets of major cities, peasants burning manor houses, armed bands clashing with uniformed troops, and crowned heads rolling in the dust to the delight of their mortal enemies. By this standard, the Industrial Revolution could hardly be considered a revolution. It was not a sudden and violent over- throw of the prevailing status quo; rather, it was a slow, drawn-out process that proved to be by and large peaceful in nature. Nevertheless, the Indus- trial Revolution altered the world more profoundly than anything since the development of agriculture many thousands of years ago. What was the Industrial Revolution? Basically, it was a transformation from the production of goods by hand to the production of goods by ma- chine. It also included a growing concentration of machines within single structures or series of connected structures called factories. The Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain about the middle of the eighteenth cen- tury and gradually spread throughout the world. It continues to evolve to- day as nonindustrialized countries struggle to industrialize and industrialized ones adopt new and more efficient technologies. A unique set of circumstances combined to provide fertile ground for the Industrial Revolution in eighteenth-century Great Britain. For a start, Brit- The power looms for weaving pictured here greatly accelerated the production of textiles. Although the Industrial Revolution provided employment and a rising standard of living, factories were not as clean and orderly as this prmt might suggest. Reproduced from the Collections of the Library of Congress Industrial Revolution 3 ain was blessed with an abundance of natural resources necessary for the industrialization process. - Joel Mokyr(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1 The Industrial Revolution and the New Economic History JOEL MOKYR 1 Almost a century has passed since the publication of Arnold Toynbee’s famous Lec-tures on the Industrial Revolution (1884).2 Historians of all persuasions have since come to the conclusion that the Industrial Revolution in Britain constituted a new point of departure in human history, an event of such moment to daily life that it compares to the advent of monotheism or the development of language. Conse-quently, a vast literature has emerged dealing with its various aspects, written by his-torians, economists, and sociologists, both left wing and right wing, English and foreign. Little agreement has emerged among the experts about the fundamental questions. There is, first, the mere question of definition: what exactly was the Indus-trial Revolution?3 Of the many attempts to sum up what the Industrial Revolution meant, Perkin’s is perhaps the most eloquent. In his words, it was “a revolution in men’s access to the means of life, in control of their ecological environment, in their capacity to escape from the tyranny and niggardliness of nature ... it opened the road for men to complete mastery of their physical environment, without the inesca-pable need to exploit each other” (Perkin, 1969, pp. 3-5). More changed in Britain than just the way in which goods and services were produced. The nature of family and household, the status of women and children, the role of the church, how people chose their rulers and supported their poor, what they knew about the world and what they wanted to know-all of these were transformed. It is a continuing project to discover how these noneconomic changes affected and were affected by economic change. The Revolution was, in Perkin’s irresistible phrase, a “more than industrial revolution.” By focusing on economics we isolate only a part, though a central part, of the modernization of Britain.- Joel Mokyr(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1The Industrial Revolution and the New Economic HistoryJOEL MOKYR1Almost a century has passed since the publication of Arnold Toynbee’s famous Lectures on the Industrial Revolution (1884).2 Historians of all persuasions have since come to the conclusion that the Industrial Revolution in Britain constituted a new point of departure in human history, an event of such moment to daily life that it compares to the advent of monotheism or the development of language. Consequently, a vast literature has emerged dealing with its various aspects, written by historians, economists, and sociologists, both left wing and right wing, English and foreign. Little agreement has emerged among the experts about the fundamental questions. There is, first, the mere question of definition: what exactly was the Industrial Revolution?3 Of the many attempts to sum up what the Industrial Revolution meant, Perkin’s is perhaps the most eloquent. In his words, it was “a revolution in men’s access to the means of life, in control of their ecological environment, in their capacity to escape from the tyranny and niggardliness of nature … it opened the road for men to complete mastery of their physical environment, without the inescapable need to exploit each other” (Perkin, 1969, pp. 3–5). More changed in Britain than just the way in which goods and services were produced. The nature of family and household, the status of women and children, the role of the church, how people chose their rulers and supported their poor, what they knew about the world and what they wanted to know—all of these were transformed. It is a continuing project to discover how these noneconomic changes affected and were affected by economic change. The Revolution was, in Perkin’s irresistible phrase, a “more than industrial revolution.” By focusing on economics we isolate only a part, though a central part, of the modernization of Britain.Difficult and ambitious questions have been posed. What were the causes of the Industrial Revolution? Why did it occur when it did? What were the effects on the economic and social welfare of the population? What were the roles played by agriculture, population growth, political elements, transportation, and foreign trade? No consensus had emerged on any of these questions by the early 1960s.4- eBook - PDF

Economic History

Made Simple

- Bernard J. Smales(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Made Simple(Publisher)

SECTION ONE THE EMERGENCE OF THE FIRST INDUSTRIAL NATION 1760-1830 CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION What is Economic History? The study of economic history, as an academic discipline, attempts to provide a systematic and integrated explanation of our economic past. It portrays man's efforts to provide himself with goods and services in order to satisfy his basic needs of food, drink, clothing and shelter. This involves a study of agriculture, industry, trade and commerce, both from the point of view of economic trends and institutional changes. Economic history frequently spills over into the allied fields of political and social history, particularly when it is concerned with the wellbeing of different groups during the course of economic change, but invariably it is much less dependent upon personality. Sir George Clark's definition of economic history is that it. . . 'traces through the past the matters with which economics is concerned. These are the thoughts and acts of men and women in those relations which have to do with their work and livelihood, such relations as those of buyers and sellers, producers and consumers, town dwellers and countrymen, rich and poor, borrowers and lenders, masters and men or, as we say nowadays, employers and employees, and unemployed too. In economic history there is never a definite starting point.' The Concept of an Industrial Revolution Most people refer to the 'Industrial Revolution' in Britain when describing the striking economic changes that took place in the British economy in the second half of the eighteenth and early part of the nineteenth centuries, when Britain was transformed from being mainly an agrarian and rural society to being increasingly an industrial and urban one. It must be remembered, however, that this period only witnessed the rise of modern industry, not the rise of industry as such, since slow and sporadic growth had been taking place long before the eighteenth century. - eBook - PDF

Western Civilization

A Brief History, Volume II since 1500

- Jackson Spielvogel(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Chapter Outline and Focus Questions 20-1 The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain Q Why did the Industrial Revolution occur first in Great Britain, and why did it happen when it did? What were the basic features of the new industrial system created by the Industrial Revolution? 20-2 The Spread of Industrialization Q How did the Industrial Revolution spread from Great Britain to the European continent and the United States, and how did industrialization in those areas differ from industrialization in Britain? 20-3 The Social Impact of the Industrial Revolution Q What effects did the Industrial Revolution have on urban life, social classes, family life, and standards of living? What were working conditions like in the early decades of the Industrial Revolution, and what efforts were made to improve them? THE FRENCH REVOLUTION dramatically and quickly altered the political structure of France, and the Napoleonic conquests spread many of the revolutionary principles to other parts of Europe. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, another revolution—an industrial one—was transforming the economic and social structure of Europe. Although the pace of this transformation was slower, the changes it produced were no less fundamental. The Industrial Revolution caused a quantum leap in industrial production. New sources of energy and power, especially coal and steam, replaced wind and water to build and run machines that dramatically decreased the use of human and animal muscle power and at the same time increased productivity. This in turn called for new ways of organizing human labor to maximize the benefits and profits from the new machines; factories replaced workshops and home workrooms. Many early factories were dreadful places with difficult working conditions. Reformers, appalled at these con- ditions, were especially critical of the treatment of married women. - eBook - PDF

Western Civilization

A Brief History, Volume II: Since 1500

- Jackson Spielvogel(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

C H A P T E R 20 The Industrial Revolution and Its Impact on European Society CHAPTER OUTLINE AND FOCUS QUESTIONS The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain Q Why did the Industrial Revolution occur first in Great Britain, and why did it happen when it did? What were the basic features of the new industrial system created by the Industrial Revolution? The Spread of Industrialization Q How did the Industrial Revolution spread from Great Britain to the European continent and the United States, and how did industrialization in those areas differ from industrialization in Britain? The Social Impact of the Industrial Revolution Q What effects did the Industrial Revolution have on urban life, social classes, family life, and standards of living? What were working conditions like in the early decades of the Industrial Revolution, and what efforts were made to improve them? CRITICAL THINKING Q What role did government and trade unions play in the industrial development of the Western world? Who helped the workers the most? CONNECTIONS TO TODAY Q How do the locations of the centers of industrialization today compare with those during the Industrial Revolution, and how do you account for any differences? Power looms in an English textile factory ª World History Archive/Alamy THE FRENCH REVOLUTION dramatically and quickly altered the political structure of France, and the Napoleonic conquests spread many of the revolutionary principles to other parts of Europe. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, another revolution—an industrial one— was transforming the economic and social structure of Europe. Although the pace of this transformation was slower, the changes it produced were no less fundamental. 477 Copyright 2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). - Various Authors(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

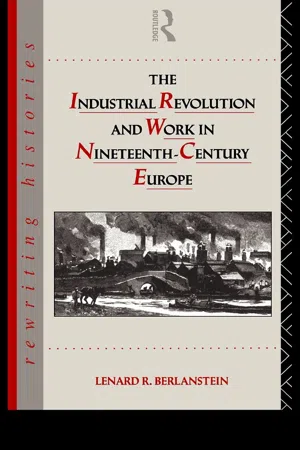

Equally it is misleading to force the parallel with a political event - a single, once-and-for-all phenomenon -because the Industrial Revolu- tion is rather the initiating phases of a continuing sequence. Thus are born other semantic and definitional problems of the 'second' and succeeding 'industrial revolutions' which 'stage' theories of historical change usually occasion. Judged against the criteria of the onset of higher rates of industrial growth and structural change, as Dr Hartwell claims, eighteenth-century England, building upon the previous slow processes of development which had been distinguishing Europe from all other societies, saw the emer- gence of new economic forces of momentous import. For these reasons the Industrial Revolution has become a focus of interest for all economic historians, economists, and other social scientists concerned with the problems of initiating and fostering economic growth in the 'third world' today. For if the Industrial Revolution stands at one of the great watersheds of history it marks also the greatest divide in the contemporary world - that between the poor and the rich nations. PETER MATHIAS e.Acknow ledgements The editor and publishers wish to thank the following for permission to reproduce the articles listed below: Professor F. Crouzet for 'England and France in the Eigh- teenth Century: A Comparative Analysis of two Economic Growths' (translated by Mrs J. Sondheimer from Annales, Vol. XXI, No 2, I966); Miss Phyllis Deane for 'The Industrial Revolution and Economic Growth: The Evidence of Early British National Income Estimates' (Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. V, No. I, I957, published by the Univer- sity of Chicago Press); Dr Elizabeth W. Gilboy for 'Demand as a Factor in the Industrial Revolution' (from Facts and Factors in Economic History, Harvard University Press, I9F); Dr R.- Lenard R. Berlanstein(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Their successors, who wrote from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, were influenced by the rise of development economics and by the post-war efflorescence of western capitalism and so rewrote the Industrial Revolution once more, this time as the first instance of ‘economic growth’. Finally, since 1974, as economic growth has become simultaneously less attractive and less attainable, the Industrial Revolution has been given another new identity, this time as something less spectacular and more evolutionary than was previously supposed. Such is the outline of economic history writing on the Industrial Revolution to be advanced here And, in the light of it, a more speculative attempt will then be made to explore the mechanism by which this process of generational change and interpretational evolution actually operates. I The years from the 1880s to the early 1920s were the first period in which self-conscious economic historians investigated the Industrial Revolution, and they did so against a complex background of hopes and fears about the society and economy of the time, which greatly influenced the perspective they took on it. Neo-classical economists like Marshall a were moderately buoyant about the economy during this period: but for politicians, businessmen and landowners, the prospects seemed less bright. 2 Prices were falling, profits were correspondingly reduced and foreign competition was growing: faith in unlimited THE PRESENT AND THE PAST 3 economic progress was greatly diminished. 3 Royal commissions investigated depressions in industry, trade and agriculture; the Boer War b revealed a nation whose military were incompetent and whose manhood was unfit; and tariff reform was partly based on a recognition that there were, in the economy, unmistakable signs of decay.- eBook - PDF

Design and Culture

A Transdisciplinary History

- Maurice Barnwell(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Purdue University Press(Publisher)

1 INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 1750–1870 Steam, Iron, and Glass FROM FIELD TO FACTORY Agriculture was the prime economic force in Britain for centuries — its dominance began to wane with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. 1 Thomas Carlyle, a young, unknown Scottish writer, composed “Signs of the Times,” which was published in the Edinburgh Review in June 1829. The phrase found popular support among prominent novelists of the day. “A lengthy era of rural, agronomic civilization was chang-ing precipitously. Opinions and beliefs that had seemed fixed certainties and were almost univer-sally shared became broadly challenged. Profound changes in science and technology fostered and fueled stunningly swift changes in the ways in which multitudes of people gained their living, organized their lives, and conducted their expe-rience.” 2 Carlyle’s concerns were repeated in his later works Chartism (1839) and Past and Pres-ent (1843). Carlyle was not alone. Three other distin-guished writers, Friedrich Engels, William Cob-bett, and Benjamin Disraeli, as well as novelists Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gas-kell, and George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), were also critics of the times. All foresaw the dra-matic and fundamental changes that would be created by industrial capitalism and that “its im-pact was not only economic, but also cultural, bringing the nation to the very brink of a preci-pice.” 3 Here is but one representative quote from Thomas Carlyle: Were we required to characterise this age of ours by any single epithet, we should be tempted to call it, not an Heroical, Devo-tional, Philosophical, or Moral Age, but, above all others, the Mechanical Age. It is the Age of Machinery, in every outward and inward sense of that word; the age which, with its whole undivided might, forwards, teaches and practises the great art of adapt-ing means to ends. Nothing is now done directly, or by hand; all is by rule and calcu-lated contrivance. - eBook - PDF

Western Civilization

Beyond Boundaries

- Thomas F. X. Noble, Barry Strauss, Duane Osheim, Kristen Neuschel(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

575 A s the French Revolution gave way to the upheavals of war in continental Europe, across the Channel fires belched flame and smoke from England’s fac- tory chimneys, lighting the night sky and blocking the day’s sun. The painting on the left depicts Shropshire, England, in 1788, a region previously renowned for its natural beauty. Industrial activity had already transformed its landscape beyond recognition. Abraham Darby (1676–1717) and his descendants built one of the largest and most important concentrations of ironworks in Shropshire because it con- tained the ideal combination of coal and iron deposits. In the 1830s, the French socialist Louis Blanqui (blahn-KEE) (see page 615) suggested that just as France had recently experienced a political revolution, so Britain was under- going an “industrial revolution.” Eventually, that expres- sion entered the general vocabulary to describe the advances in production that occurred first in England and then dominated most of western Europe by the end of the nineteenth century. Although mechanization trans- formed Europe, it did so unevenly. In many areas, the changes were gradual, suggesting the term revolution was not always appropriate. Great Britain offered a model of economic change because it was the first to industrialize; each nation subsequently took its own path and pace in a continuous process of economic transformation. Industrial development left its mark on just about every sphere of human activity. Scientific and rational methods altered production processes, removing them from the home—where entire families had often participated—to less personal workshops and factories. Significant numbers of workers left farming to enter mining and manufactur- ing, and major portions of the population moved from rural to urban environments.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.