History

Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution was a period of rapid industrial development in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, characterized by advancements in steel production, electricity, and the widespread use of machinery. This era saw the rise of mass production, the expansion of railroads, and the development of new communication technologies, leading to significant economic and social changes.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Second Industrial Revolution"

- G. Zanda(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

52 4 The Second Industrial Revolution (late 1800s and early 1900s) Daniela Coluccia 4.1 Introduction Historians usually talk about the Second Industrial Revolution (or second phase of industrial capitalism) to refer to a complex system of factors that came about between the final decades of the 1800s and the first decades of the 1900s. These factors could be listed as follows: the use of electricity in the world of production and consumption; the development of new technologies, some of which are connected to the use of electricity; the more developed nations reach the devel- opment phase known as ‘technological maturity’; institutionalization of research and development within enter- prises; growing use of capital in the production process, expansion of mar- kets, the arrival of mass products and mass consumption and the advent of large corporations; the development of studies and practices in management – and, in particular, studies in the organization and motivation of personnel – with the aim of improving the efficiency of the factors of production of the enterprise and of satisfying the demands of the emerging class of paid workers. These innovations strengthened and consolidated industrial capitalism and caused a considerable shift in power within companies and in soci- ety in favour of those that held the strategic factor of production, capi- tal. This happened first in the USA and in Europe, but did not happen simultaneously in all countries. • • • • • G. Zanda (ed.), Corporate Management in a Knowledge-Based Economy © Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited 2012 The Second Industrial Revolution 53 In the last 30 years of the 19th century, industrial capitalism became almost dominant in England. However, it encountered difficulty in France, where it suffered because of its alliance with the lower middle class and small farmers.- eBook - ePub

Management, Organisations and Artificial Intelligence

Where Theory Meets Practice

- Bartosz Niedzielski, Piotr Buła(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3 steam locomotive. The first of these inventions contributed to a significant reduction in the cost of fuel in metallurgical furnaces, while the second enabled the transportation of cargo across substantial distances in less time. In consequence, civilizational development at the onset of the 19th century became even more dynamic. To a significant extent, which is worth emphasizing, it was a result of efforts of talented engineers, chemists, physicists or technologists, rather than an accident or a gift from the gods.The term “industrial revolution” was used again in 1936 by the French sociologist and psychologist Georges Friedmann to describe the changes that were taking place in Europe and in the United States during the first half of the 19th century, related to the effects of mass production, which utilized assembly lines, division of labor, development of the human being and that of entire societies.4 It is commonly accepted in literature that the Second Industrial Revolution (Industrial Revolution 2.0) falls in the period 1870–1914. This means that, after one hundred years from the beginning of the First Industrial Revolution, the world and humanity had to face another one, this time characterized by even greater upgrades and challenges. The greatest innovations connected with the Second Industrial Revolution era, which strongly affected the dynamics of industrial development at that time, were directly linked to two new energy sources: electricity (electric motor) and oil and natural gas (internal combustion engine). With them, the industrial world witnessed a sudden transition from conventional production methods to more innovative ones, based on new technologies, which changed the earlier processes of manufacturing and processing goods that took place in the majority of British and US factories. However, the changes, important from the point of view of technology and innovation, were taking place not only in industry, but also in communications or transportation. In the case of communications a considerable role for human development and the world was played initially by the telegraph,5 which revolutionized communication systems and allowed people to communicate remotely and then by the telephone,6 the forefather of the smartphone, which is now considered the foundation of contemporary communication systems. In transportation, groundbreaking for that era and later also the world’s further history, were discoveries by US aviation pioneers, the Wright brothers.7 - eBook - ePub

- Lennart Schön(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

4 The breakthrough of industrial society, 1890–1930

The Second Industrial Revolution

The upturn of the 1890s was accompanied by a swarm of innovations that were to be described as the Second Industrial Revolution. New opportunities were created for industry and growth. Applied science, research, engineering and rational planning became fundamental ingredients of production (Landes 1972). Meanwhile, a host of new products and processes emerged. However, it was not just production and the economy that were changed: an advanced industrial society was in the making.Development blocks surrounding engines

Several innovations were at the heart of the Second Industrial Revolution, particularly in the area of motors and power engineering. In that sense, there were major similarities between the First and Second Industrial Revolutions. The steam engine had been the central innovation in the First Industrial Revolution. Now the electric motor and the internal combustion engine played that role.New development blocks arose around these innovations that would drive growth for a long time to come. There were also a number of similarities when it came to the background of the innovations. Both the steam engine and the motors were developed as new processes spread in the iron and steel industry. Both industrial revolutions were preceded by growing energy needs and rising fuel prices.Energy crisis on the way

The earliest industrialisation had been basically confined to areas with coal deposits, primarily in Britain, Belgium and northern France (Pollard 1981). High transport costs for coal had contributed to that concentration of heavy industrial production. But increased coal mining and improved transport had brought down the relative price of coal from the mid-1820s to the 1850s, helping the steam engine and industrialisation to spread. More extensive industrialisation after 1850 multiplied the energy needs of European industry. Although transport improved further (which was important for the fuel supply), productivity growth in coal mining could not keep up with demand. Relative price trends reversed, and the price of coal began to rise steadily in the 1860s compared with most other industrial products. - eBook - ePub

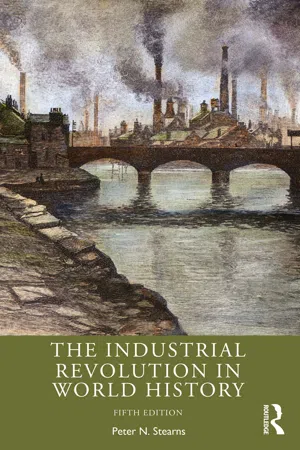

- Peter N. Stearns(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Part 2 The Second Phase, 1880–1950 The New International CastPassage contains an image

7 The Industrial Revolution Changes Stripes, 1880–1950

Three major developments defined the second phase of the industrial revolution in world history from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth: industrialization outside the West, redefinition of the West’s own industrial economy, and growing involvement of nonindustrial parts of the world, along with an overall intensification of international impact. This phase began to take shape in the 1870s and 1880s, though no firm markers divided it from previous trends. Several Western societies, including Germany and the United States, were still actively completing their basic transformation, becoming more fully urban and committed to the factory system as their manufacturing power presented new challenges to Britain, the established industrial power. Large numbers of new workers, fresh from the countryside, still poured into German and, particularly, U.S. factories, experiencing much of the same shock of adjustment to a new work life that earlier arrivals had faced a few decades before. But even as many trends continued, the phenomenon was changing shape (see Map 7.1 ).Map 7.1 The Industrial Revolution in Europe, 1870–1914.Second-Phase Trends

In terms of long-range impact, international developments were particularly striking. Several major new players began to industrialize by the 1880s and were the first clearly non-Western societies to undergo an industrial revolution. Russia’s industrial revolution had a massive impact on global power politics. Japan’s revolution altered world diplomacy as well and ultimately had an even greater effect on the international balance of economic power. The focal point of the second phase of the industrial revolution involved the transformation of these two key nations. By 1950, when their revolutionary phases were essentially complete, neither had matched the West’s ongoing industrial strength. But a key measure of these later industrial revolutions—like those of the United States and Germany before—was the capacity of these societies to grow more rapidly than the established industrial powers. Later industrial revolutions could allow newcomers to begin to catch up, and this feature marked many aspects of world history from 1880 to the present day. - eBook - ePub

Process Safety

An Engineering Discipline

- Pol Hoorelbeke(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

This chapter described how society evolved in the period 1700 to 1900. Rapid population growth coupled with increased urbanization brought fundamental changes to the social system.More food had to be produced and the demand for new materials increased. Global trade accelerated, which in turn increased the demand for better roads, better and faster transport, a new banking system.These changes formed the basis of the transition to new manufacturing processes in Europe and the USA, now known as the First Industrial Revolution.This First Industrial Revolution created the demand for more and better machines, new materials, more energy, new products, etc., which resulted in the Second Industrial Revolution. The large land owners invested more and more money in new industries, factories and mines.The Second Industrial Revolution was a period of rapid industrial development, characterized by the construction of railroads, large-scale iron and steel production, widespread use of machinery in manufacturing, greatly increased use of steam power, widespread use of the telegraph, use of petroleum and the beginning of electrification. It also was the period during which modern organizational methods for operating large-scale businesses over vast areas started to be used.The Second Industrial Revolution gave rise to large industries that employed many people; these included construction of railways, textile factories, steel factories and coal mines.The social and economic changes that engulfed Europe in the nineteenth century were exceptional and never seen before. In 1850, the percentage of the population working in agriculture was 75% in Italy, 60% in Germany, 52% in France and 22% in Great Britain. The rapid industrialization brought these figures down at the turn of the century (1900) to 60% in Italy, 35% in Germany, 42% in France and 9% in Great Britain.The nineteenth century was the century of revolutions. The French Revolution of 1789–1799 was a political uprising that massively reduced the power and privileges of the nobility and the clergy. This political revolution which started in France spread over the entire continent. The traditional land-owner aristocracy was undermined by the forces of economic change and political reforms. A new hybrid social elite emerged based on citizen values such as economy, hard work, freedom, austerity, equality and responsibility. These values dominated society and politics in large parts of Europe and were reflected in sanitation and hygiene, reforms in criminal law and participation of the respectable working class. - eBook - PDF

- Frank Kidner, Maria Bucur, Ralph Mathisen, Sally McKee(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

In the second half of the nineteenth century, however, while textiles and iron continued to be vital to the industrial economy, new materials and processes— steel, chemicals, petroleum—revolutionized indus-trial production. Mass-Produced Steel The most important of these was mass-produced steel. Steel combines the advantages of pig iron (being hard and durable) and wrought iron (being flexible and resistant to crack-ing). The advantages of steel had long been known, but before the mid-nineteenth century, there had been no economical method of mass-producing steel. Then, in the 1850s and 1860s, the Siemens-Martin (open-hearth) process revolutionized steel produc-tion. In 1861, before these innovations had begun to spread throughout Europe, the total steel output in Britain, France, Germany, and Belgium was around 125,000 tons. By 1871, production had more than tripled and in 1913 exceeded 30 million tons—over eighty times the amount made in 1871. This mas-sive output went into rails, railroad engines and cars, steamships, and increasingly sophisticated weaponry. Steel also allowed new forms in architecture: its strength and flexibility meant that buildings could expand upward to an unprecedented degree. The skyscraper—an American invention—was the result. The ten-story Home Insurance Building in Chicago was erected in 1885, but expansion skyward was lim-ited by the need to climb stairs. In 1887, this prob-lem was solved with the invention of the high-speed elevator, and by the early twentieth century New York City had a number of skyscrapers, including the 23-1 The Second Industrial Revolution ❱ » What technological advances were made during the Second Industrial Revolution? ❱ » How did technological advances alter work and leisure? In the second half of the nineteenth century, in particu-lar after 1870, industrial and technological changes so profoundly altered European life that the era is called the Second Industrial Revolution. - eBook - PDF

Career Confusion

21st Century Career Management in a Disrupted World

- Tracey Wilen-Daugenti(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

49. https://www.amacad.org/content/publications/pubContent.aspx?d=1053. 50. Ibid. 51. Ibid. 52. Ibid. 53. Ibid. 54. Ibid. 55. Ibid. 56. Ibid. 57. Ibid. 58. http://ushistoryscene.com/article/second-industrial-revolution/. 59. Ibid. 60. http://www.history.com/topics/inventions/cotton-gin-and-eli-whitney. 61. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Fulton. 62. http://study.com/academy/lesson/mechanical-reaper-invention-impact-facts.html. 63. https://prezi.com/6cog1z4rqqjt/the-first-combine-was-made-by-hiram-moore-in-the- us-in-1834/. 64. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Deere_(inventor). 65. https://www.biography.com/people/margaret-fuller-9303889. 66. https://www.biography.com/people/susan-b-anthony-194905. · 2 · THE Second Industrial Revolution The Second Industrial Revolution (1870–1914) made America the world’s leading industrial power. By 1913, the United States produced one-third of the world’s output, besting the combined productivity of the United King- dom, France, and Germany. 1 It was a great leap forward for technological and social progress—so soon after the Civil War (1861–1865). Factors that enabled this leap forward included an abundance of natural resources (coal, oil, iron), large and cheap labor supplies, newer sources of power (electricity), railroads, American inventors and inventions (long distance communications with Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone in 1876; Thomas Edison’s light bulb in 1879, which allowed factory work to continue at night), and strong gov- ernment policies. Before the 19th century, if you weren’t working on your family’s farm, you performed some type of skilled trade. But the advent of industrialization meant there was less need for apprenticeships or craftsmen. There was also less need for commoditized labor; cheap commodities became readily available as the Second Industrial Revolution progressed, effectively ending the subsis- tence lifestyles of American farmers. - eBook - ePub

Re-Envisioning Global Development

A Horizontal Perspective

- Sandra Halperin(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3 Industrialization and the expansion of capital Core and periphery redefinedThe development of capitalism, according to most accounts, involved sweeping changes, first in agriculture and then, in its second and most vital stage, in industry. The previous chapter challenged conventional assumptions about the agricultural revolution which, it is generally thought, laid the basis for England’s industrial ‘take-off’. This chapter challenges widely held assumptions about the industrial revolution.We can begin with the term ‘industrial revolution’ itself. As historians have long argued, the use of the term ‘industrial revolution’ to describe the changes that took place in Europe during the latter half of the eighteenth century is misleading (Clark 1957: 652).1 The term suggests that there occurred at that time a revolution in technology that transformed the means of production. But there was no technological revolution, no transformation in means of production during the period of what we call the ‘industrial revolution’. Large-scale mechanized manufacturing had existed, in Europe as elsewhere, for at least a century (more likely several); and while Europe at that time saw an increase in the scale of industrial production, involving a massive mobilization of human and material resources and a reorganization of production processes, this revolution of scale, as it might be called, involved neither a revolution in technology nor a transformation either of means or relations of production.What, then, is meant by the term ‘industrial revolution’? The previous chapter ended by noting that, in the eighteenth century, powerful groups in Europe had launched a broad campaign to dismantle regulations tying production and investment to local economies. As this chapter will recount, by the end of that century, these efforts had succeeded in bringing about changes designed to ‘disembed’ local economies and accelerate the globalization of capital.2 Conventional historiography would lead us to assume that these developments, along with other changes at the time, were a result of the ‘industrial revolution’. But this chapter will argue that it was precisely these changes – the disembedding of local economies and the globalization of capital – that came to be called, misleadingly, the ‘industrial revolution’. Wherever industrial production expanded, whether of manufactured or agricultural or mineral goods, it was in order to increase exports. In Britain (‘the first industrial nation’), the capture of overseas markets through military means, and the successful struggle by aristocrats and wealthy merchants to free capital from state regulation, provided opportunities for these groups to profit from increasing overseas sales. It was only then - eBook - ePub

- Tom Kemp(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter Two Industrialization in historical perspectiveAbout 200 years ago, unbeknown to those living at the time, a fundamental revolution began in the history of mankind, which was to lead to the development of the world as we know it today. First in Britain, then in a few areas of Europe and North America, a structural transformation, seen in perspective as having been in preparation for centuries, shifted the balance of productive activity from agriculture to industry and opened up boundless possibilities for increasing the productivity of human labour. This process, best described as industrialization, brought into existence those forms of labour and styles of living distinguishing the modern world from the past, the advanced countries from the ‘backward’ ones.The central characteristic of industrialization is machine production, the basis for an enormous growth in productivity and thus for economic specialization in all directions. It created a new environment for work, with its own demands and laws – the factory. It brought about the concentration of workers in big industrial units and the growth of towns to house the working population, creating a new urban environment for social living. The new type of town, growing mushroom-like with industrialization, was not an adjunct to a predominantly agrarian society but a new dynamic force for change, the home of the majority of the population in a predominantly industrial society.Industrialization imposed new forms of the labour process by bringing together many workers under one roof to operate machines driven by power. Workers were incorporated into an articulated system of division of labour in which they performed only one small part of the total labour going into production. Characteristically, the new labour force was ‘free’ – not bound to the soil or to a single employer, but dependent wholly upon the market. The instruments of production were concentrated in the hands of a small class of industrial capitalists and represented a heavy outlay of capital upon which it was necessary to obtain a profitable return. A new form of industrial discipline had to be elaborated and imposed, one dependent not upon formal coercion but upon the worker’s need to earn a living and his fear of losing his job. Formally free, unlike the majority of producers in history before, the new industrial proletariat worked under the threat of economic deprivation. It was wholly dependent upon the labour market, or, what comes to the same thing, on the employers as a class. This new class division summed up the social relations of production of industrial capitalism; it was the source of conflicts and problems of the kind that still dominate modern society. - eBook - PDF

- Merry Wiesner-Hanks(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Many machines and machine parts that had earlier been made out of wood were increasingly made of the much more durable iron or steel, and iron began to replace stone as a construction material. In the periodization of human history into eras developed at roughly this time, the Iron Age began in the second millennium bce , but in terms of iron’s impact on everyday life, the Iron Age really began in the nineteenth century. Early steam engines were so wasteful of energy that they only made economic sense where fuel was cheap and did not need to be transported very far, so the iron industry grew up in coal-mining regions, and cities such as Newcastle and Liverpool expanded at an amazing rate. They were filthy and lacked enough housing, clean water, or sanitation services for their residents; diseases such as typhus and tuberculosis spread easily. Work was structured by the need to use machines efficiently, so tasks became more routinized and the work day even longer and more regimented in coal-fired factories than it had been in water-powered ones, and far more so than in household forms of production. Wages were low, but often higher than those in the countryside, and the opportunities to escape parental and family control were greater, so the new industrial cities sucked in young people, as cities always had. The British state Cotton, slaves, and coal 293 supported industry through tax policies that favored investors, high tariffs or outright bans on manufactured goods from elsewhere, and naval power that could enforce laws requiring colonies to trade only with Britain. In 1750, Britain accounted for less than 2 percent of production around the world, while in 1860 its share was more than 20 percent, including two-thirds of the world’s coal and more than half of its iron. - eBook - ePub

- Mary Kilbourne Matossian(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

10 THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION IN BRITAINTo found a great empire for the sole purpose of raising up a people of customers, may at first appear a project fit only for a nation of shopkeepers. It is, however, a project altogether unfit for a nation of shopkeepers, but extremely fit for a nation whose government is influenced by shopkeepers.—Adam Smith It is one thing to describe the Industrial Revolution, which began in late-eighteenth-century Britain. It is another to explain how it began.From the perspective of world history, economic growth and technological innovation did not necessarily occur together. Economic growth at times occurred in the absence of technological innovation. Using existing technologies more extensively, merchants could maintain economic growth by increasing the volume of trade. That was in accordance with the principle of specialization with complementarity.Even when a technology is possible and desirable, no one may see fit to develop it. A notorious case was Faraday’s discovery in 1831 of the principle of the electric dynamo, which was little utilized for fifty years even though entrepreneurs knew about it. Now large dynamos provide the current to light our buildings, run our electric appliances, and operate our computers.Two economic historians, Crafts and Harley, estimated the annual industrial growth in England. English industrial output increased tenfold between 1743 and 1850, from an index of 2.63 in 1743 to 21.20 in 1850 (1913 = 100).1 The growth process was gradual, not explosive. It depended upon the use of new technologies that intensified resource use.Certain regions in England, notably Lancastershire, led the way. By the early nineteenth century other regions in western Europe had also become centers of innovation: the Rhineland, Alsace, Flanders, Swiss alpine areas, Salerno, and Moscow-Ivanovo. Industrial growth was not a coordinated national effort.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.