History

Civil Rights Organizations

Civil rights organizations are groups that advocate for the rights and equality of all individuals, particularly those who have historically faced discrimination. These organizations work to address issues such as racial segregation, voting rights, and equal access to education and employment. They have played a crucial role in shaping legislation and social attitudes towards civil rights.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

5 Key excerpts on "Civil Rights Organizations"

- eBook - ePub

Human Rights for Pragmatists

Social Power in Modern Times

- Jack Snyder(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

Depending on the context, they can also provide an organized basis for group self-defense or the coercive use of force. Unlike episodic protests and riots, social movements capable of sustained effort require a centralized leadership cadre to develop an ideology, articulate a common framing discourse, formulate strategy, recruit existing groups and individuals to join the movement, and organize coordinated sequences of action. 28 Professionalized organizations, such as NGOs, provide another way of organizing civil society to promote rights. 29 Typically, they have a professional staff funded by foundations, private donors, governments, or international organizations, and occasionally also have a public membership that plays a limited role in core organizational activities. Rather than organizing mass protests or coercive actions such as civil disobedience, rights NGOs advocate for the adoption of rights norms, collect information about the violation of existing rights norms and laws, demand compliance, comment on or occasionally participate in legal actions to enforce rights, and lobby governments and other powerful actors to sanction or shun rights violators. Allied organizations may deliver services to rights-deprived populations, as in the rights-based approach to development or humanitarian assistance. They may mount grassroots efforts to persuade local communities to abandon abusive cultural practices such as female genital cutting. Thus, they do some of the same tasks as mass social movements, especially framing issues and formulating strategies for publicity, but the most prominent human rights NGOs mainly lobby others to take direct action rather than organizing it themselves. Parties, Movements, and NGOs Working Together—or Not Since it is possible to have mass social movements, NGOs, and political parties pressing simultaneously for rights, asking which gets better results is not necessarily the right question - eBook - ePub

Much Sound and Fury, or the New Jim Crow?

The Twenty-First Century's Restrictive New Voting Laws and Their Impact

- Michael A. Smith(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- SUNY Press(Publisher)

Chapter 8

Civil Rights Groups Respond

Kevin AndersonIntroduction

The central question in a democratic government is, How are citizens’ preferences translated into public policy? Voting as an essential right in a democratic polity is a fundamental element of self-government, and for minority groups access to the ballot is critical to not only basic tenets of democracy but to the protection of rights relative to the majority within their society. How can minorities that historically have been discriminated against and have had to fight for full access to all the rights of full citizenship, respond to policy changes that might create obstacles to the ballot box and that, in context, might complicate other aspects of their everyday life?Over the course of American history, the response of civil rights groups and their allies can be roughly grouped into three categories. The legislative strategy is focused on changing the law, for example, the Civil Rights Act of 1965. The legal strategy focuses on seeking redress through the courts. This includes a series of rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court and lower courts declaring various state laws and practices unconstitutional, and it started well before the heyday of the civil rights era in the 1950s and 1960s. Finally, the protest strategy focuses on using protest as a means of building support and pressing for change. It is exemplified in the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Today the BlackLivesMatter movement has engaged on this front and represents a new perspective on voting rights in contemporary politics.Historical Strategic Responses

African Americans have employed numerous tactics to secure and maintain access to the ballot box. At the core of each of these strategies is both an argument for the protection of the individual right to vote as essential to citizenship and the idea of perfecting democratic government in America. The earliest protest actions against voter exclusion rested on the idea of disenfranchisement as a violation of individual liberty inherent in denying citizens the right to vote. Over time, this concern was married to a broader argument that voter exclusion undermined the core idea of democratic government. These two principles helped define the strategic choices of those fighting for the elective franchise. The passage of Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments after the Civil War during the Reconstruction era created new opportunities for political activism. The Union Leagues, originally founded in Northern states during the Civil War to support the war effort, began organizing in the South to boost the new amendments by helping to register and mobilize voters in Southern cities, such as Richmond, Raleigh, and Nashville (Hahn, 2003). The work of these groups helped to undergird the first sustained government action taken to bring African Americans into the political arena. The ability of the national government to act on behalf of a formally excluded population established a pattern in which the goal of political activism for some within the newly freed population is to organize and use the national government to force the entire nation (specifically, state governments) to extend individual rights to all citizens. To define political rights in general, and access to the ballot specifically, as a national concern became a key aspect of the new African American political class. - eBook - ePub

- Paul Von Blum, Frank Reynoso(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- For Beginners(Publisher)

Chapter 1:

THE HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF THE MODERN CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

“No human history is rootless, and we see the fullest meaning of the post–1945 events only as we dig deeper. Such probing work could take us back to the coast of Africa, to the earliest liberation struggles on the prison slave ships, and could open up the long, unbroken history of black resistance . . .”Vincent Harding, We The People: The Long Journey Toward A More Perfect Union in EYES ON THE PRIZE CIVIL RIGHTS READER, 1991Virtually all Americans and billions of people throughout the world know something about the American civil rights movement, often correctly viewing it as one of the most important political and moral crusades of the 20th century. The movement has entered even the most conventional U.S. history texts and is widely celebrated throughout educational, media, and political institutions in America and elsewhere. In the United States, the major highlights and figures of the civil rights movement are celebrated during African American History Month each February, with television specials, school pageants, public lectures and speeches, governmental resolutions, and a wide variety of special events throughout the nation.Over the years, moreover, a vast civil rights literature has been created, much of it focusing on the dramatic events of African American resistance to oppression and segregation from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s. Some of this material, however, is scholarly and only marginally accessible to the general public. Moreover, many of the more accessible works focus predominately or even exclusively on this narrow historical timeframe and on widely recognized public figures like Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.Parks and King are iconic figures whose courage and international fame are well earned and entirely justified. But both of these majestic figures would be among the first to proclaim that they stood on the shoulders of thousands who came before them—including countless anonymous women, men, and children who put their bodies, and sometimes their lives, on the line to free their people from slavery, Jim Crow, and more subtle forms of racism. A deeper, more comprehensive history of the civil rights struggles should equally include the lesser-known stories of black liberation struggles and incorporate the efforts of the ordinary people without whom such leaders as Dr. King and others would never have emerged. - eBook - ePub

- Erik Love(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

Through until the 1980s, it was generally accepted that the reforms won by the 1960s civil rights campaigns would remain durable and effective for the long term—for decades or more. After all, the movement made racial inequality into a deeply moral issue, and when an advocate spoke up about racism, it might be perceived as racist to stand in opposition to that advocate. The framework whereby an identity-based advocacy organization files grievances has stood the test of time, but the methods available to those organizations for advocacy have changed considerably in the decades since the apex of the civil rights movement.As it turned out, advocacy designed to expand legal protections for racialized minority communities became unconventional, or even illegitimate, at the end of the 1900s. The conservative reaction to the disruptions of the 1960s social movements meant that any discussion of special protections for racialized groups—from desegregation, busing, and affirmative action to voting rights protections—became stigmatized and controversial at best. By the 1980s, such efforts were branded as “radical,” even “racist” or “reverse racist.” The conservative turn of the 1970s, personified in the successful Nixon campaign to empower the “silent majority” of Americans who wanted “peace and quiet,” sparked a successful counter-movement to delegitimize civil rights protections established through what conservatives derided as “identity politics.”In the face of these shifts in the political climate, anti-racist campaigns defended affirmative action policies and other anti-discrimination programs built on the legacy of the civil rights movement by relying less and less on racial identity recognition and group rights, and instead increasingly taking up issue-based approaches. Civil Rights Organizations began to emphasize the common benefit of their campaign for all Americans, regardless of race. In other words, a “post-racial” and “colorblind” climate emerged, and many advocates for civil rights adjusted their strategies away from the now-controversial “identity politics.” - eBook - ePub

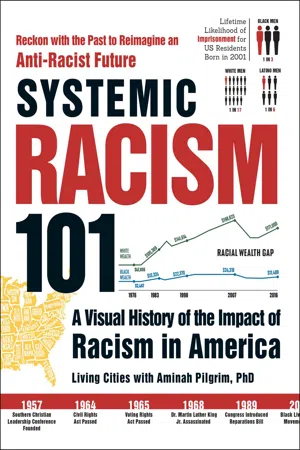

Systemic Racism 101

A Visual History of the Impact of Racism in America

- Living Cities, Aminah Pilgrim(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Adams Media(Publisher)

In some ways, the history of systemic racism can be distilled into a set of patterns. One core pattern is the consistent tension between African Americans’ human rights activism and white supremacists’ opposition through policies or violence. The civil rights movement (CRM) is representative of this pattern.This chapter will review some of the key figures, events, and moments of the CRM, beginning with its foundations in the late nineteenth century. Continuing the focus on anti-Blackness, it becomes clear, reviewing this history, that with each attempt at racial uplift on the part of African Americans, the ex-Confederates and those with what historian Paul Ortiz calls “white business supremacist” interests made their opposition more fierce and more wide-reaching. The perceived threat that African Americans posed to white economic interests had to be halted. The result of that opposition would be strengthening the systemic racism in every sector of the country—government, business, housing, healthcare, education, and popular culture. This racism was met with organizing for justice and equity at every turn.EARLY ORGANIZING FOR RACIAL JUSTICE: THE “RIVER” OF BLACK PROTEST

The earliest organizing for racial justice and civil rights was led by the enslaved people and free Blacks who fought for slavery to end and for all to have freedom. After emancipation, the newly freed joined the ranks of those who fought for African Americans to have full citizenship, the franchise, and other protections. Among the front-runners of this movement were Sojourner Truth, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, David Walker, and Frederick Douglass. These activists understood the meaning of the country’s founding documents and made it their life’s work to see them made true.Conventional timelines or mainstream representations of the civil rights movement usually concentrate on the 1950s and 1960s. Yet that timeline excludes the century or more of organizing that precipitated the twentieth century’s climactic “Second Reconstruction.” The late African-American historian, civil rights activist, and MLK Jr. speech writer Vincent Harding described this timeless fight for liberation and the tradition of anti-racist activism as a never-ending “river” of Black protest.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.