History

Colonization of Brazil

The colonization of Brazil refers to the period when the Portuguese established control over the territory, beginning in the early 16th century. This colonization involved the exploitation of natural resources, the introduction of Portuguese culture and language, and the establishment of a plantation economy based on the labor of indigenous peoples and later enslaved Africans.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Colonization of Brazil"

- Nicholas Canny, Anthony Pagden, Nicholas Canny, Anthony Pagden(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

Their in-ability to do so and Portugal's attempt to return to the colonial status quo eventually brought the political rupture in 1822, but with a son of the Por-tuguese king on the throne as an independent monarch in Brazil. The Colonists and the Colony At its origins Brazil was modeled on Portugal's other overseas posses-sions. During the first thirty years when contact was intermittent and es-sentially carried out by private contractors, the model seems to have been the feitorias or trading stations of the West African coast, but with the cre-ation of donatarial captaincies in the 1530s, a shift toward a plan for colo-nization somewhat akin to Portugal's previous experience in Madeira can be seen. 3 Unlike uninhabited Madeira or the Azores, the Portuguese en-countered in Brazil a previously unknown savage, non-Christian people, and the crown by the mid-sixteenth century pointed to its responsibilities as a bearer of the cross as the reason for its conquest in Brazil. The mission-ary effort from this point forward always stood alongside economic motives in Portuguese considerations or justifications of their presence in Brazil. 2 Fernando A. Novais, Portugal e Brasil na crise do aruigo sistema colonial (1777-1808) (Sao Paulo, 1979) and Jose Jobson de A. Arruda, () Brasil no comercio colonial (Sao Paulo, 1980) are two fundamental monographs on the changing relationship between Brazil and Portugal in this period. ' Harold B. Johnson, The Donatary Captaincy in Perspective: Portuguese Backgrounds to the Settlement of Brazil, Hispanic American Historical Review 52, 2 (May I972):2O3—214. 18 FORMATION OF IDENTITY IN BRAZIL In social or religious terms Brazil was created to reproduce Portugal, not to transform or transcend it. There was no attempt there to create a city on the hill, as the Puritans would do in New England, or a Quaker com-monwealth, as in Pennsylvania.- eBook - PDF

The Masters and the Slaves

A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilization

- Gilberto Freyre(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Sergio Buarque de Hollanda is preparing an interesting paper on Brazilian expansion to the west. On this subject see Marcha para Oeste (Westward March), by Cas- siano Ricardo (Rio de Janeiro, 1939). The Portuguese Colonization of Brazil 27 most powerful colonial aristocracy in the Americas. Over it the King of Portugal may be said, practically, to have reigned without ruling. The representatives in the municipal council, the political expression of these families, quickly limited the power of the kings and later that of imperialism itself, or, better, the economic parasitism that sought to extend its absorbing tentacles from the Kingdom to the colonies. Colonization through soldiers of fortune, adventurers, exiles, "new- Christians" fleeing religious persecution, shipwreck victims, slave- dealers, and traffickers in parrots and lumber left practically no trace on the economic life of Brazil. This irregular and haphazard mode of settling the land was so superficial and lasted so short a while that politically and economically it never reached the point of becoming a clearly defined system of colonization. Its purely genetic aspect, on the other hand, should not be lost sight of by the historian of Brazilian society. - eBook - ePub

- Johannes Kabatek, Albert Wall, Johannes Kabatek, Albert Wall(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

versus the enslaved, since there was a significant portion of the population consisting of poor white peasants (Fausto 1995, 58–59).At the beginning of colonization, the movement of migrants from Europe was characterized as spontaneous yet selective: adult men of different social strata predominated, coming mostly from the Northwest of Portugal and the Atlantic islands, as well as a considerable number of new Christians (Jews required to “convert” to Christianity). The almost exclusive presence of men, from the beginning, fostered intense racial mixing, which was fundamental to the creation of the Brazilian population. It is also relevant from the perspective of a linguistic history, since mixed-race peoples are a link between linguistically-distinct worlds.The 1530s saw another predominantly male migratory movement, which was also selective but not spontaneous: the arrival of enslaved Black Africans. Brazil was the last country to abolish slavery in the West, only in 1888. Slave trade remained legal until 1850, and although it is not possible to precisely determine how many were brought to Brazil, it is estimated that between 8,000,000 and 11,000,000 enslaved Africans were brought to the Americas, and approximately 4,900,000 of this total were brought to Brazil (Schwarcz/Starling 2015, 82). In the 16th century, Portuguese smugglers used the term “Guinea negro” to describe Africans. In an inquiry into what Guinea was in the early days of slave trade, Oliveira (1997) reported that all of West Africa north of the Equator, from the Senegal River to Gabon, was then known as Guinea, and stated that the term also came to be applied to populations south of the Equator. It can be concluded, therefore, that since the beginning, languages were transplanted from two sub-Saharan regions, and would characterize the entire history of slave trade in Brazil: those of West Africa, including languages ranging from Senegal to Nigeria, and Bantu, with languages spanning the entire continent south of the Equator. The languages of the African continent are classified into four groups: Congo-Kordofanian, Nilo-Saharan, Afroasiatic, and Khoisan; Congo-Kordofanian is subdivided, in turn, into two families: Niger-Congo and Kordofanian.2 - eBook - PDF

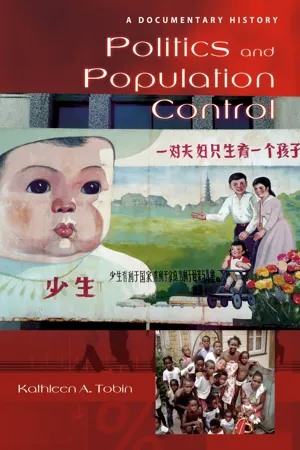

Politics and Population Control

A Documentary History

- Kathleen A. Tobin(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

(London: J. T. Ward and Co., 1808, pp. 37-43) This British description of Brazil is a noteworthy example of the early- nineteenth-century perspective on colonization and population. Its timing 62 Politics and Population Control was significant, as Great Britain acknowledged that Brazilian independence was at hand, and it makes a detailed examination of Brazilian culture, geog- raphy, and population, etc., as desirable for establishing future trade rela- tions. The author's analysis of population composition reflects general European notions of culture, behavior, society, and race, noting the ways in which the Portuguese colonized over the centuries. In addition, the descrip- tions of the Portuguese, particularly in their practice of Catholicism, suggest that the British saw even greater potential in extending their own influ- ence—which they regarded as more civilized—in Brazil. In essence, rela- tions that developed between Great Britain (and eventually other nations, including the United States) and various Latin American nations upon their independence can be described as neocolonial. Clearly, numbers of inhab- itants were important to the observer, but an understanding of the popula- tion's composition was key to future development. The ancient inhabitants of Brasil differed very little in stature or complexion from the Portuguese themselves; but much exceed them in strength and vigour. Some lived in villages, and others moved about according to their humours. These villages consisted of only three or four very large houses; in each of which a whole family or tribe lived together, under the authority of the eldest parent. They procured subsistence by fowling and fishing, and made up the rest of their diet with the fruits of the earth; but though they had no luxurious plenty, yet, in so fertile a country, they were in no great danger of want. - eBook - PDF

Teaching History and the Changing Nation State

Transnational and Intranational Perspectives

- Robert Guyver(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

The Portuguese diaspora is explored, and economic, political, religious and cultural factors are examined. Acculturation and miscegenation are part of the expansionist movement of Portuguese people, as well as concepts such as (religious) mission; colonization; and ethnic, Indigenous and cultural diversity. The relationship between Portugal and Brazil arises in various issues which begin with the arrival in Brazil (Land of Vera Cruz) of the Portuguese navy commanded by Cabral in 1500; being of relatively little interest if compared with the Cape Route and its rich spice trade, the former exploration focused on natural resources (dye plants and exotic birds). After the restoration of independence in 1640, and the spice trade crisis in the late sixteenth century, the Portuguese Crown’s interests turned to Brazil and its economic potential, associating sugar or tobacco plantations with the slave trade, and later focused on gold, coffee and cotton. This triangular relationship between Europe, Africa and America (Brazil) was mirrored in the exchange of different cultures that crossed over several generations and manifested not only in the ethnic crossroads (miscegenation) but also in the cultural intersection (acculturation, assimilation, interculturality), depending on the perspective of colonizer or colonized. Brazil is once again a content area within this diachronic approach, especially when studying the period of the French invasions which led to the moving of the entire Portuguese court to Brazil in 1808 and to a change in Brazil’s status, then considered as a kingdom joined to Portugal. After the American and French revolutions fostered the desire for independence of Brazil in 1822, there followed the rise of the liberal movement. - Richard P. Schaedel, Jorge E. Hardoy, Nora Scott-Kinzer, Richard P. Schaedel, Jorge E. Hardoy, Nora Scott-Kinzer(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Mouton(Publisher)

The landholders preferred slave labor, and at the same time the settlers resented the working conditions and the bonds that tied them to the plantation as if they were slaves (Da Costa 1966: 78-83). 2. Discussions on the advantages of European migration increased during the 1870's. Brazil had been the first Latin American country to propose and begin plans for European colonization. On numerous occasions plans for colonization by the indigenous population were also proposed, but rarely implemented. But these plans only partially responded to the labor needs. Excluding some colonization attempts made by the Portuguese government during the eighteenth century (in the period after independence), repeated experiments in colonization were made, especially in the south of the country; these plans gave preference to northern Europeans, Germans, and Swiss. Through the initiative or with the help of the imperial government, the explicit goal was to populate the country. Although welcome, voluntary immi-grants, especially Portuguese, had concentrated themselves in the cities (especially Rio de Janeiro) or were tied in one way or another to the dynamic sector of the economy, that is to say, to export. Colonization, in contrast to voluntary immigration, would fill the unpopulated areas and assure control over the national territory. In Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina important colonies were established along the route toward the north, but in Rio de Janeiro Migrations and Urbanization in Brazil, 1870-1930 509 the expansion of coffee cultivation limited the available land for colonization, and in Minas such lands had not really existed since mining began (Da Costa 1966). Official colonization often failed be-cause of the lack of economic viability for a basically political project: without access to markets, colonies rapidly scattered or regressed to subsistence economies (Tavares et al. 1972).- eBook - PDF

Depositions

Roberto Burle Marx and Public Landscapes under Dictatorship

- Catherine Seavitt Nordenson(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University of Texas Press(Publisher)

12 DEPOSITIONS the public landscape ran boldly counter to the economic development policies of the regime. Burle Marx transformed a conservationist spirit into a prescient environmen- talist position that constructed Brazilian modernity as inseparable from an ecological positioning of nature. The Arrival of the Royal Court, 1808–1821 The construction of culture and education by a government apparatus, with an undercurrent that embraces nature as a critical aspect of that culture, has an extended history in Brazil, which was colonized by the kingdom of Portugal begin- ning with the arrival of Pedro Álvares Cabral on April 22, 1500. The very name “Brazil” is drawn from the colony’s first major export, the hardwood tree species pau- brasil or brazilwood (Caesalpinia echinata), prized for its red dye. Massive colonial extraction of pau-brasil from Brazil’s coastal forests nearly led to its extinction—the early Portuguese colonization was funded through this exploitative deforestation. Yet with the arrival of the Portuguese royal family and court three hundred years later, seeking refuge from Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Portugal during the Peninsular War, a state-sponsored program of both education and culture was initiated in Brazil. The enhancement and support of the natural environment, now seen as a valuable asset of the new tropical kingdom, was considered an imperative. In 1808 Queen Maria I of Portugal, her son Prince Regent João, and the entire Portuguese court of approximately 20,000 people arrived in Rio de Janeiro in a mas- sive flotilla, escorted by the British navy. The royal family established itself on a large property north of the city center, the Quinta da Boa Vista, and expanded the site’s sumptuous manor house that would become known as the Paço de São Cristóvão. - eBook - ePub

- Antonio Luciano de Andrade Tosta, Eduardo F. Coutinho, Antonio Luciano de Andrade Tosta, Eduardo F. Coutinho(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

donatários) would encourage Portuguese migration and stimulate economic activity in each region. Although the captaincy system did not flourish (only two captaincies, Pernambuco and São Vicente, were economically profitable), it accelerated sugar cultivation and led to the settlement of new coastal areas.The land and labor that sugar production required further aggravated Portuguese relations with indigenous populations. At the time of the Portuguese arrival in 1500, an estimated 2–5 million indigenous people inhabited the land encompassing the modern nation-state of Brazil. Although European diseases killed many Amerindians, particularly those living along the coast, enslavement and mistreatment at the hands of the Portuguese probably killed many more. To resist enslavement or resettlement on a Jesuit mission, many Amerindians left coastal regions and headed to the interior. Royal laws declared indigenous slavery illegal in 1570, but exceptions were made for Amerindians who had been captured in a “just war.” Brazilian settlers had begun to turn to African slavery, long in use on the Portuguese Atlantic islands, but African slaves were more expensive to purchase than negros da terra (“blacks of the earth,” a term used in early colonial Brazil to refer to indigenous people). Bandeirantes led numerous expeditions into Brazil’s interior in search of Amerindian captives, invoking just war on shaky legal grounds. From the Portuguese word for flag, “bandeira,” the word bandeirante refers to small armed bands separate from a larger company. During the colonial period, bandeirantes explored Brazil’s interior, searching for gold, runaway slaves, and Amerindian captives to sell as slaves. Bandeirantes helped ensure the survival of indigenous slavery well into the 18th century. When the captaincy system showed signs of struggling, the Portuguese Crown sent a royal governor, Tomé de Sousa, along with a largely male contingent of some 1,000 colonists, many of whom were degredados - eBook - PDF

Migration and Immigration

A Global View

- Maura I. Toro-Morn, Marisa Alicea, Maura I. Toro-Morn, Marisa Alicea(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

After 1695, massive Portuguese immi- gration occurred. It has been estimated that at least 300,000 —and as many as 500,000 —Portuguese came to Brazil at this time (Wagley, 1971, p. 48). This immigration effectively doubled the number of Europeans in the total population in Brazil. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Portugal could conceivably have become a French colony, as Napoleon rapidly expanded his political power all over Europe. In 1808, fearing the worst, the royal family of Por- tugal moved its court to Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil. Right after Napoleon lost power, the Portuguese monarchy, however, went back to Lisbon in 1821. Although it lasted only a very short time, the Portuguese kingdom in Rio de Janeiro actually helped Brazil develop economically and fostered trade with European nations. Once again, a demand for plantation labor caused large numbers of African slaves to be imported from other Portuguese col- onies, such as Angola and West Africa (which was geographically relatively close to Brazil). Returning to Lisbon, the Portuguese monarchy left the Crown Prince in Rio de Janeiro and let Brazil be governed independendy under him. Although the country became self-governing when Prince Pedro BRAZIL 23 I declared its independence on September 7, 1822, there were few political and economic changes in Brazil, and the country still operated as a colony of the Portuguese kingdom. During the period of colonial growth and independence, more European planters arrived in Brazil, and more African slaves were imported to be plan- tation laborers. The approximate number 1 of slaves imported in the sixteenth century was about 100,000 but grew in the seventeenth century to about 600,000. In the eighteenth century some 1.3 million slaves arrived in Brazil, and in the nineteenth century about 1.6 million. - eBook - ePub

Establishing Exceptionalism

Historiography and the Colonial Americas

- Amy Turner Bushnell(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

7 Brazil: The Colonial Period Stuart B. Schwartz Long the domain of the retired lawyer or the avocation of the literate elite, the writing of colonial Brazilian history has since the end of the first Vargas era (1945) come increasingly into the hands of professional academics. To a greater or lesser extent these men employ modern critical techniques of research and analysis, and thus colonial Brazilian historiography has begun to move from dilettantism to professionalism. This is not to say that a great deal of marginalia fails to appear in the pages of the state historical publications, where inflated discursos still outweigh the occasional excellent article, but, in general, Brazilian and foreign scholars have made great strides in the description and analysis of the colonial heritage. Progress, of course, has been uneven and certain aspects have received far more attention than others. Legal history, a favorite of the nineteenth-century bacharéis, has suffered a decline, while economic studies are all the rage. Such trends reflect the interests of the age and are tied to the concern of Brazilians with their future as well as their past. Euphoria, however, should not dominate an essay on colonial, Brazilian historiography, for as the carioca historian José Honório Rodrigues (153) somberly indicated in 1967, much Brazilian historical writing is still elitist and antiquarian in approach. 1 But, as the work of Rodrigues himself and others shows, change has taken place. This essay, therefore, will emphasize achievement and progress rather than stagnation and inertia. Futhermore, space and the author’s limitations place certain restrictions on the materials cited. The discussion will by necessity be highly selective and will concentrate on recent trends rather than on a comprehensive listing of all books - eBook - PDF

- Robert M. Levine(Author)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Brazil has become more than ever a country of vast economic inequalities, where the small affluent elite lives in luxury in the midst of an ocean of the hard pressed and destitute. The plight of some groups, notably Indians and urban street children, has received world attention. In recent decades it has been disclosed that the government’s National Indian Foundation, the successor to the Indian Protection Service (SPI) founded in 1910, was for years complicit in widespread actions against the interests of the Indian population, including violence. The problem of nationwide poverty remains unsolved, and in some ways it is worsening under Brazil’s embrace of the free market economy. Page 25 CULTURAL CHARACTERISTICS AND RELIGION Since the nineteenth century, Brazilians have considered their language culturally superior to Portugal’s, which Brazilians consider provincial and oldfashioned. The foundation in 1897 of the Brazilian Academy of Letters provided the means to validate Brazilian Portuguese, with its rich regional variations and flexible willingness to absorb words and phrases from a wide range of sources, including indigenous peoples and immigrants. The colonial era witnessed artistic expression at all levels of society. Members of the elite enjoyed Baroque music as sophisticated as in Europe. Some plantations and mines had slave orchestras. Craftsmen constructed sidewalks of inlaid stone; carpenters turned out handsome furniture, using native mahogany and jacarandá. Colonial architecture followed the Portuguese style of simple exteriors of whitewashed stone. Brazil lacked the monumental cathedrals of Spanish America, but in the royal captaincy of Bahia and in the small towns of the mining region in Minas Gerais, the high point of colonialera culture was reached in the beautiful interiors of churches, many of them decorated with expressive statues and icons, all heavily gilded.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.