History

Ida B Wells

Ida B. Wells was an influential African American journalist, educator, and early leader in the civil rights movement. She is best known for her fearless anti-lynching crusade, using her writing to expose and challenge the widespread violence and discrimination against African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Wells' activism and advocacy continue to inspire and resonate today.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Ida B Wells"

- eBook - PDF

Icons of African American Protest

Trailblazing Activists of the Civil Rights Movement [2 volumes]

- Gladys L. Knight(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931) Library of Congress Ida B. Wells-Barnett lived an extraordinary life of protest against segrega- tion, discrimination, racism, and racial violence against African Americans. Her claim to fame was her leading the way in the fight against lynching. She was a journalist, lecturer, suffragist, and social reformer, as well as wife and mother to four children. Both her life of activism and her personal life were revolutionary in that Wells-Barnett frequently challenged societal norms and the expectations of other activists, the ramifications of which provoked a torrent of criticism. Wells-Barnett’s activism was especially valiant considering she was an African American and a woman in a world that granted few privileges, rights, or freedoms to her race or gender and the fact that she often fought alone without the support or involvement of her colleagues, community, or the thriving organizations of the period. Late in Wells-Barnett’s life, her achievements were minimized, overlooked, and, ultimately, shrouded by a conservative and male-dominated organizational leadership. Those who sang their loudest praise on Wells-Barnett’s behalf, particularly in the years leading to her death in 1931, were African American women of the wom- en’s club movement. Subsequent recognition was lacking, and the memory of Wells-Barnett was fast becoming obsolete until her life and heroism began to be lionized in a number of publications and articles. Contemporary scholars such as John Hope Franklin, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Cornel West were among those whose works restored Wells-Barnett to her rightful position as a twentieth-century icon of African American protest. EARLY LIFE Ida Bell Wells, the oldest of eight children, was born a slave on July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi. This was just two years before the end of the Civil War and the subsequent liberation of millions of African Ameri- can slaves in the American South. - eBook - ePub

Struggle on Their Minds

The Political Thought of African American Resistance

- Alex Zamalin(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

This chapter will discuss someone who devoted her lifework to raising consciousness about lynching and in doing so became one of the most important activist-intellectuals in American history: the African American journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Born to enslaved parents in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1862, Wells came to public prominence when, in 1884, she directly resisted the “separate but equal” segregationist logic behind Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) a decade before it was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, by refusing to give up her seat in the “ladies car” of a railroad in Tennessee after she was told by the train’s conductor to go to the rear car, designated for “smokers.” Then, after one of her black friends, Thomas Moss, was lynched in Memphis in 1892, Wells become a militant antilynching activist, fusing investigative reporting with the burgeoning field of social science to argue that lynching was a form of vigilante justice that desecrated American cultural commitments to the rule of law. Wrong were those who thought lynching was nothing more than a misguided attempt to enforce antiquated, if not frivolous, codes of Southern chivalry enacted by uneducated masses who foolishly believed the machinery of justice was just too slow and procedural to mete out swift punishments. Wells theorized lynching as a form of racial terrorism aimed against the black community. Her analysis gave way to a progressive political agenda in which Wells attempted to persuade American lawmakers that lynching was a national crime that required national legislation - eBook - PDF

Icons of Black America

Breaking Barriers and Crossing Boundaries [3 volumes]

- Matthew Whitaker(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931) Department of Special Collections, University of Chicago For three decades spanning approximately 1890–1920, Ida Bell Wells (Wells-Barnett after her marriage) dedicatedly worked to better the life situations of people of African descent and women living in the United States. To work to benefit her people, Wells-Barnett’s efforts can be grouped into two major categories. On the one hand, she took on the enormous task of exposing the propaganda and correcting the falsities espoused by the white, often Southern, press and politicians. She dedicated herself to the goal of correcting white, mainstream beliefs concerning African Americans, which spanned from the innocent—yet ignorant—to the virulently racist. On the other hand, Wells-Barnett passionately devoted her energies to community-building, helping to organize institutions and services to assist African Americans. An underlying, foundational belief in humanity drove Wells-Barnett in her many activities; this passion for human dignity provided Wells-Barnett with her unwavering, uncompromising positions on every cause she took on. Without hesitation, she spoke her mind to Southern whites, Northern white liberals, and African Americans with whom she disagreed. Her fearless, articulate, and outspoken nature, during a time of oppression and violence often considered the nadir of African American history, makes Ida B. Well-Barnett an icon of black America. Ida B. Wells was born to parents who were enslaved in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862, during the Civil War. Holly Springs represented both rural and urban lifestyles in the nineteenth century, with cotton planta- tions and an iron foundry for the Mississippi Central Railroad representing the two primary forms of employment. Ida’s father, Jim Wells, worked as a carpenter in the city. - eBook - ePub

Through the Eyes of Titans: Finding Courage to Redeem the Soul of a Nation

Images of Pastoral Care and Leadership, Self-Care, and Radical Love in Public Spaces

- Danjuma G. Gibson(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Cascade Books(Publisher)

1894 . It is but one example of the intellectual, emotional, and spiritual complexity that permeates the individual and collective inner world of black subjectivity in the face of racial hatred and oppression. The multiplicity of subject matter outlined by Wells in just a few sentences is far too weighty and robust to be sustained and encapsulated by the simplicity of a racial reconciliation conversation posited by many institutions that make the decision to address issues around race and racism, but perhaps lack sufficient intellectual and spiritual capital, and even moral authority, to have effective dialogue. In this one passage, Wells expresses being overwhelmed by the human atrocities, feeling abandoned and misunderstood, isolated, morally outraged, disillusioned, and ultimately, clinically traumatized.Ida B. Wells was arguably the leading public theologian and voice of the anti-lynching campaign at the turn of the twentieth century. Without her critical research on white racist terrorism and its nationwide campaign of lynching that propped up white supremacy, we might well be largely ignorant to this very day of the depth of the atrocities that occurred. Lynching remains a prominent historical symbol of white supremacy that was underwritten, in part, by the church in America, directly or indirectly. In the most essential expression of her personhood, Ida B. Wells was able to find her voice. Moreover, in finding her voice, she became a formidable opponent to be reckoned with, not only for those who were outright supporters of lynching (directly or indirectly through their silence), but for those who attempted to justify lynching through racist narratives of perverse black male sexuality (i.e., lynching was in response to black men raping white women).In this chapter, I offer up a concise psychospiritual analysis of Ida B. Wells that emphasizes the strength of her authentic self in the context of racial violence and extremity. My analysis focuses on this vital question:How did Ida B. Wells discover her authentic self and find her journalistic voice and moral protest against the public lynching of thousands of black people that became commonplace, a trend that swept the country towards the end of the nineteenth and well into the twentieth century in America - eBook - PDF

Advocates of Freedom

African American Transatlantic Abolitionism in the British Isles

- Hannah-Rose Murray(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

8 “The Black People’s Side of the Story” Ida B. Wells and the Anti-lynching Crusade in Britain 1893–1894 During a breakfast meeting in Parliament in 1894, activist and journalist Ida B. Wells spoke out against the legacy of slavery and lynching. She wrote an account of the gathering and described how prominent reform- ers pledged their support to her cause: I gave an address of forty minutes and then the great temperance advocate Sir Wilfrid Lawson, spoke for England, Mr. John Wilson of Scotland, and Mr. Alfred Webb for Ireland, expressing horror of lynching and promising to do all they could to bring influence to bear to have Americans move in this matter. The photograph of the lynching of C.J. Miller, which was reprinted in THE INTER OCEAN last summer and which I have in my possession, went around the beautifully decorated tables as I talked. 1 Following in the footsteps of numerous nineteenth-century Black activists before the Civil War, Wells exploited visual culture to stir the British public to action and urged the individuals before her and the press to bestow respectability upon her cause. Through her rhetoric, and the photograph itself, she contrasted southern barbarity with the civilized meeting around the “beautifully decorated tables,” and highlighted the absurdity of American freedom. Throughout the nineteenth century, formerly enslaved activists had shown their scars, exhibited whips and chains, and read testimonies from state laws or southern newspapers, and Wells now used photography along similar lines to condemn white 1 Daily Inter Ocean, June 25, 1894, in Mia Bay and Henry Louis Gates Jr. (eds.), Ida B. Wells: The Light of Truth: Writings of an Anti-Lynching Crusader (2014), 188–195. 292 supremacy and oppression. Unlike previous male activists, however, Wells had to navigate the double embodiment of race and gender on stage and perform as a genteel, humble woman who was forced into this public line of work because of lynching’s barbarities. - eBook - ePub

The Other Reconstruction

Where Violence and Womanhood Meet in the Writings of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Angelina Weld Grimke, and Nella Larsen

- Ericka M. Miller(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1 Wells-Barnett refuses to fit neatly into the category of “integrationist” or “black nationalist,” and so defies a popular mode of classifying African American intellectuals. I argue that Wells-Barnett’s writings on lynching also resist conventional codification, in content as well as form. This resistance reflects the scope of her vision regarding mob violence in American society. Her writings indicate that any approach to ending such violence must be multi-faceted and must speak to all members of society, for all have played a role in sustaining it.Born to Elizabeth and James Wells in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862, Ida Wells lived her first two years as a slave. The Civil War ended shortly after her birth, bringing with it the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment prohibiting slavery, and later she attended Rust College, where she excelled. But Ida’s youth was short, for in 1878 a yellow fever epidemic spread through Holly Springs, taking her parents, Elizabeth and James, as well as a brother and sister with it. As the oldest of six remaining children, Ida became the sole supporter of the family at the age of sixteen.Seeing that employment prospects were dim in Holly Springs, Ida Wells moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where she accepted a teaching job and attended Fisk University and the Lemoyne Institute. Soon thereafter, a sharp awakening to the legal, institutional, and social discrimination African Americans still faced 30 years after emancipation and a compulsion to address it inspired a long and illustrious career in journalism. Writing under the name “Iola,” her talent attracted much recognition. The Reverend William J. Simmons, president of the National Baptist Convention and editor of the Negro Press Association, hired Wells as a correspondent for his paper, and later she became the elected secretary to the National Press Association, acquiring high praise from colleagues such as I. Garland Penn and T. Thomas Fortune for her courage, sharp mind, and eloquence. In 1889 Wells became part-owner and editor of Free Speech and Headlight - eBook - ePub

Black Leaders and Ideologies in the South

Resistance and Non-Violence

- Preston King, Walter Earl Fluker(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In the 1890s, she was an international figure and (for many) a celebrated heroine (McMurray 1999). But the fact that she occupied past space has not and should not generate sweeping concessions regarding her historical salience. The acclaim posthumously accorded Wells falls far short of that accorded to the many figures with whom she might be compared, such as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman and Mary McLeod Bethune, not to mention Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Wells, rightly or wrongly, has for long been largely written out of the script, taking account of her role as a social thinker and reformer in Afro-America. Only recently has she been identified by some as a subject fit for significant biographical reconstruction. The question arising is whether the narrative space from which she has been excluded, or in which her role has been ‘down-sized’, is a form of historical falsification, intentional or inadvertent. Her case provides an interesting example of how history may falsify or distort – which is the same as failing to be representative – of the past it supposedly depicts. The eminent and admirable Du Bois was one of the first and most notable of those who consigned Wells to the anteroom of historical silence and narrative anonymity. In a brief obituary notice, appearing in the NAACP house organ, The Crisis (June 1931), he reduces Wells to the role of an ‘easily forgotten’ pioneer in the anti-lynching cause. Du Bois in effect makes a brisk case for her historical truncation, if not excision, along three lines. First, he implies that Wells had only one arrow in her quiver – the opposition to lynching – and perhaps not the best arrow of its kind. Second, he claimed the anti-lynching cause was, in any event, later ‘taken up on a much larger scale by the NAACP’, which in part means by Du Bois himself - eBook - PDF

Ethical Complications of Lynching

Ida B. Wells's Interrogation of American Terror

- A. Sims(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Wells, like theologian Kelly Brown Douglas, realized that “with the support of sexual discourse, lynching became an effective way to prevent Black people from gaining power politi- cally, economically, or socially.” 3 Wells’s social justice advocacy was far-reaching. Her ability to maneuver in international circles is admirable. But her capacity to interpret motives greatly enhanced her ability to communicate effec- tively her position on lynching as well as her views on franchise and racial discrimination on public carriers and in employment. 4 Wells was instrumental in launching the women’s club movement in America and was a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). But her directness and outspokenness often contributed to moments of ostracism and misunderstandings. 5 Along with her numerous accomplishments a distinctive character- istic of Wells was her willingness to challenge dominant perspectives, irrespective of race or gender. From her we gain an appreciation for an unrelenting determination that is often a prerequisite to explore the intricacies of practices that contribute to the perpetuation of legally sanctioned forms of terror. The ability to offer an alternative viewpoint requires a commitment to assess a situation accurately, to be cognizant of our biases and lesser strengths, to be willing to accept constructive criticism, to make the necessary personal sacrifices, to document our findings, and to articulate our position. In addition, Just Act 129 Wells’s evaluation of the causes of lynching in the United States points to several major themes that continue to warrant further investigation. In particular, her research suggests that there is a direct correlation between murders committed by mobs and the economics of racism, the myth of womanhood, and the power of collective strength. In 1892 vigilante justice was primarily an unchecked aspect of American civilization. - eBook - ePub

Ethical Prophets along the Way

Those Hall of Famers

- Rufus Burrow(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cascade Books(Publisher)

In fact, when Tom Moss and his two companions were lynched, she bought a pistol in order to defend herself from those who might come after her because of her outspokenness against lynching. She frequently had the pistol on her desk as she wrote articles on lynching. Her strong sense of her own dignity and sacredness convinced Wells-Barnett that her life was just as valuable and precious as any and that it was better to die fighting against injustice and trying to preserve one’s life than to passively allow oneself to be taken by the mob and lynched. 316 Aware of her own fundamental dignity, she would simply not give up her life without a fight to preserve it. In this she anticipated Malcolm X, whom we will meet in chapter 5. Wells-Barnett knew that among whites it was not considered a crime to kill blacks, which is why she counseled that the Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home. In addition, she declared that “God expects us to defend ourselves.” 317 Wells-Barnett proclaimed that any persons who are interested in the welfare of humanity as such, as well as “the good name of our country,” will resist lynch law with all their might, including their life. She was also eager to point to the common features of the whole of humanity. 318 In addition, she was openly and highly critical of white Southerners’ failure to acknowledge the common humanity of blacks with white people. 319 Furthermore, she rightly observed that baseness is not confined to any one race or class of people and that people of questionable character exist in every group. No group of people has a monopoly on stupidity, incivility, and immorality, although every group has individuals in it that exhibit one or more of these traits. Speaking the Truth Ida B. Wells-Barnett was adamant that educated and privileged blacks had social responsibilities and obligations to the less fortunate in their community - eBook - ePub

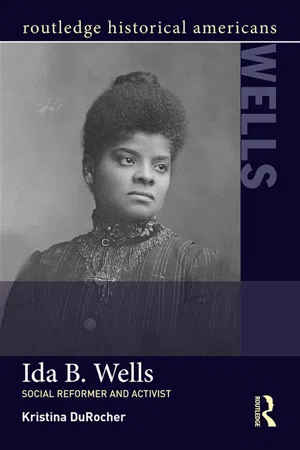

Ida B. Wells

Social Activist and Reformer

- Kristina DuRocher(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

95The white clubwomen movement that Wells alluded to in her initial “Ladies Day” speech consisted of the voluntary associations of white middle-class women whose economic positions allowed them leisure time in which to devote themselves to social issues such as sobriety, education, domestic violence, safe working conditions, sanitation, and suffrage. For black women, the clubwomen movement added an additional key component to these issues, one of “racial uplift,” the belief in combating racism by working to better the conditions of African Americans. Historian Glenda Gilmore argues that with black men essentially disenfranchised by Jim Crow laws, black women stepped in as the advocates for the race and applied the same moral rhetoric utilized by white women as part of True Womanhood in order to claim a legitimate role in public spaces.96 In carving out a space for public female activism, black women began to generate social change, and during the next decade, the clubwomen that Wells encouraged became increasingly influential within the black community.In the spring of 1894, the executive council for one of the models for this movement, The Society for the Recognition of the Brotherhood of Man, contacted Wells with an invitation for her to return to England and continue her anti-lynching campaign. Wells, hesitant to become involved again with Isabelle Mayo, negotiated not just for her expenses, but also a salary of two pounds per week. When the organizational board agreed to her terms, Wells accepted the invitation. Unfortunately, the money for her passage did not arrive before her departure date, and at the last minute, Wells asked Frederick Douglass to loan her twenty-five dollars for the fare. During her voyage, the council appraised Mayo of Wells’s return, and Mayo demanded that the Council require she publically repudiate Impey. Apparently, the SRBM Council members refused to agree to the terms and Mayo withdrew her financial support. When Wells arrived, she encountered similar circumstances to those of her first trip.97

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.