History

Wilhelm I

Wilhelm I, also known as Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig, was the King of Prussia and the first German Emperor. He played a significant role in the unification of Germany and the establishment of the German Empire. His reign marked a pivotal period in European history, characterized by the rise of Prussia as a dominant power and the formation of a unified German state.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Wilhelm I"

- eBook - PDF

Weimar Germany

The republic of the reasonable

- Paul Bookbinder(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

The federal constitution also provided for an upper legislative 5 Weimar Germany house, a Bundesrat, whose consent was needed for constitutional change and whose members were chosen by the state govern- ments. Prussia's block of seventeen delegates was sufficient on its own to prevent constitutional changes. The constitution also put great power in the hands of the chief executive, the Emperor or Kaiser, who was also the King of Prussia. The chief administrative officer of the state, the Chancellor, and his cabinet were responsi- ble to the Kaiser but not to the legislature. The personality of the Kaiser, Wilhelm II, who was Germany's ruler in 1914 at the beginning of World War I, and the nature of his inner circle of confidants were important factors in the evolution of this society. The Kaiser began his rule in 1888 as a young man who proclaimed concern for the working people of Germany and who did not appear to be a rigid conservative. His parents had embodied the liberals' hope for the future of Germany. His father, Friedrich and his mother, who was the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria of England, were intent on moving Germany towards a true constitutional monarchy where class, ethnic and religious differences would be of less importance. Wilhelm's father was critically ill with cancer when he inherited the throne from his brother Wilhelm I and died within three months. His son was in many ways closer in outlook to his uncle than to his father or mother. He rebelled against their generally more liberal orienta- tion and veered sharply away from any early promise of moder- ation. By the turn of the twentieth century, Wilhelm II had sur- rounded himself with those who encouraged his limited and most reactionary instincts. As Isabell Hull describes Wilhelm's circle of intimates, "Their milieu fostered the narrowest and most conservative aspects of Wilhelm's eclectic Weltanschauung." He spent most of his adult life trying to be something he was not. - eBook - ePub

Blood and Iron

The Rise and Fall of the German Empire

- Katja Hoyer(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Pegasus Books(Publisher)

Wilhelm’s love–hate relationship with England is a somewhat more traceable factor in his actions. Due to his close connection with the British royal family, he spent much of his childhood in England fascinated with its empire, naval power and aristocratic culture. From his grandmother Queen Victoria’s favourite residence of Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, the young prince could overlook the Solent and watch the glorious fleet of the British navy sail in and out of Portsmouth and Southampton. Fascinated, Wilhelm became a keen boatsman himself, taking part in competitions and even hosting his own Emperor’s Cup in 1904. As a boy, Wilhelm had confided to his uncle, the Prince of Wales, that he was hoping to have ‘a fleet of my own someday’. After a poor showing on the German side at Queen Victoria’s Fleet Review in 1889, Wilhelm resolved to build a navy that would be the envy of the world. He also loved the style of the English aristocracy and would often dress up to look like them. During the First World War, he had the Cecilienhof in Potsdam built in the style of a Tudor country manor. This odd fascination and rivalry with Britain meant that Wilhelm looked to the European neighbour as both a model for what he wanted to achieve with Germany and a competitor that had to be bested. It was yet another example of his childlike outlook on the world that would become a dangerous vehicle for the expansionists and warmongers in his inner circle at court.It is tempting to dismiss Wilhelm’s role from 1890 to 1914 as that of a ‘shadow emperor’ whose infantile disposition made it easy for others to manipulate him. While the victors in 1918 decided that responsibility for the First World War lay squarely with the Kaiser (his abdication was a non-negotiable precondition for peace), later generations have seen this differently. The aftermath of the Second World War began a reversal in the assessment of Wilhelm’s ability to make decisions. Keen to find meaningful connections between both world wars, historians made the forces of Prussian, militaristic court culture the narrative link. After all, Wilhelm could hardly be blamed directly for the heinous crimes committed under Hitler’s regime. This view has led to Wilhelm’s figure receding in German collective memory. He became an eccentric and misguided tool for those who really held the strings of power. This narrative is oversimplifying the matter and lets Wilhelm off too lightly. When he ascended to the throne in 1890, he had a clear vision for Germany. He wanted a unified nation with a strong central monarchy that was world-leading in terms of technological, military and naval power. To this end, he chose to pay no heed to Bismarck’s warnings about the precarious foreign policy situation, nor to the demands of the workers on the streets and in the factories. While it would be false to assume that Wilhelm led a massive rearmament programme and followed an imperialist policy in order to provoke a major European war, it is certainly true that he chose this path accepting that it might. - A. Walter(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

EMPEROR WILLIAM FIRSTLife Stories for Young PeopleEMPEROR WILLIAM FIRST THE GREAT WAR AND PEACE HERO

Translated from the German of A. WalterBY GEORGE P. UPTON Translator of “Memories,” “Immensee,” etc.WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS A. C. McCLURG & CO. CHICAGO A. C. McCLURG & CO. 1909Copyright A. C. McClurg & Co. 1909 Published August 21, 1909THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.Translator’s Preface

Upon the titlepage of the original of this little volume stands inscribed, “A life picture for German youth and the German people.” It might, with equal pertinency, have been written, “A life picture for all youth and all people.” Emperor William First was a delicate child, but was so carefully nurtured and trained that he became one of the most vigorous men in Germany. At an early age he manifested a passionate interest in everything pertaining to war. In his youth he received the Iron Cross for bravery. He served under his father in the final wars of the Napoleonic campaign, and in his twenty-third year mastered not only the military system of Germany, but those of other European countries. During the revolutionary period of 1848 he was cordially hated by the Prussian people, who believed that he was wedded to the policy of absolutism, but before many years he was the idol of all his kingdom, and in the great war with France (1870), all Germans rallied round him.After the close of this war he returned to Berlin and spent the remainder of his days in peace, the administration of internal affairs being left largely to his great coadjutor, Prince Bismarck. In connection with Von Moltke, these two, the Iron Emperor and the Iron Chancellor, made Germany the leading power of Europe. In simpleness of life, honesty of character, devotion to duty, love of country, and splendor of achievement, the Emperor William’s life is a study for all youth and all people.G. P. U.- eBook - ePub

- Robert Cole(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Interlink Books(Publisher)

What was he like, the new German emperor, grandson of Queen Victoria of England? He was twenty-nine, full of himself, and in the view of Portuguese diplomat and writer José Maria Eça de Queiroz, a man of many faces. In 1891 he described Wilhelm as, variously, a Soldier King who put changing the guard over all matters of state, a Reform King concerned only with capital and wages, a King by Divine Right ‘haughtily resting his sceptre on the backs of his people,’ a Courtier King, worldly and pompous, and a Modern King, ‘dreaming of a Germany worked entirely by electricity.’ Queiroz opined that what he actually was, or would be, was anyone’s guess.In fact, the bottom line for Wilhelm was imperialism, absolutism — to the extent the constitution allowed — and militarism. He was contemptuous of Reichstag leaders, whom he called ‘Sheep’s Heads,’ and ‘Night Watchmen,’ and once remarked that if Centre Party leader Ludwig Windthorst ever came to the Palace, ‘I would have him collared by a subaltern and three men and thrown out.’ Wilhelm began his first public address as emperor ‘To my Army,’ rather than ‘To my People.’ His military policy was to increase the army and armaments, for in his view, and that of the Imperial General Staff, an expanded Reichswehr (imperial army) was essential for Germany to achieve the great things ‘divinely’ ordained for it. He once remarked that: ‘Our Lord God would not have taken such great pains with our German Fatherland and people if He did not have still greater things in store for us’.Not everyone was impressed. Walter Rathenau (1867—1922), executive of the electoral cartel AEG and architect of Germany’s economic mobilization in the First World War, complained of Wilhelm’s ‘dilettante foreign policy, romantic conservative internal policy, and bombastic and empty cultural policy.’ And a 1903 edition of American magazine Harper’s Weekly - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

While a traditional view, promulgated in large part by the 19th and early 20th centuries pro-Prussian historians, maintain that Bismarck was the sole mastermind behind this unification, post-1945 historians see more of an opportunism and cynicism in Bismarck's manipulating of the circumstances to create a war. Regardless, Bismarck was neither villain nor saint; in manipulating events of 1866 and 1870, he demonstrated the political and diplomatic skills which had caused Wilhelm to turn to him in 1862. Three episodes proved fundamental to the administrative and political unification of Germany: the death without male heirs of Frederick VII of Denmark which led to the Second War of Schleswig (1864); the opportunity created by Italian unification in providing an ally against Austria in the Austro-Prussian War (1866); and French fears of Hohenzollern encirclement led it to declare war on Prussia, resulting in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). Through a combination of Bismarck's diplomacy and political leadership, von Roon's military reorganization, and von Moltke's military strategy, Prussia demonstrated that none of the European signatories of the 1815 peace treaty could uphold Austrian power in the central European sphere of influence and thus achieved hegemony in Germany, ending dualism. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ The Schleswig-Holstein Question From north to south: The Danish part of Jutland in terracotta, Schleswig in red and brown, and Holstein in lime yellow. The first opportunity came with the Schleswig-Holstein Question. On 15 November 1863, King Christian IX of Denmark became king of Denmark and duke of Schleswig and Holstein. On 18 November 1863, he signed the Danish November Constitution, and declared the Duchy of Schleswig a part of Denmark. - eBook - ePub

- Christopher Clark, Christopher (St Catherine'S College, University Of Cambridge) Clark(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Die Post declared that the ‘entire essence’ of the government’s Moroccan policy reflected ‘fearfulness, weakness of character [and] cowardice’:Is Prussia no longer itself? Are we become a nation of women? . . . What has become of the Hohenzollern, from whom sprang once a Great Elector, a Friedrich Wilhelm I, a Frederick the Great, a Kaiser Wilhelm I? The Kaiser appears to be the strongest pillar of French and British policy. . . . Guillaume le timide, le valeureux poltron!78This article did not command unanimous support, indeed it was widely condemned for its irreverence, but similar views were heard within the senior ranks of the military, where there was contemptuous talk of the ‘peace-Kaiser’ who had failed to defend the honour of his fatherland.79 In August 1911, the gifted young officer Erich von Falkenhayn, commander of a Guards regiment and a personal favourite of the Kaiser, observed in a letter to a friend that nothing would change in Germany as long as the Kaiser continued to be ‘determined to avoid the most extreme action’.80 In March of the following year, during the quiet spell that set in after resolution of the Moroccan crisis, he noted that the emperor remained ‘quite determined to maintain peace under any circumstances’, and added regretfully that ‘in his entire milieu there is not one individual who is capable of dissuading him from this decision’.81Wilhelm’s Impact

To what extent can Wilhelm be held responsible for Germany’s drift into deepening isolation during this era? In addressing this question we need to distinguish between the influence he could wield over the policy-making processes of the German government and his influence on the wider international environment within which German policy had to operate. We shall consider each in turn. - eBook - ePub

Supreme Leadership in Modern War

Civil-Military Relations During Competition and War

- James Lacey, Williamson Murray, James Lacey, Williamson Murray(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

10 The Iron Chancellor, the founder of the Empire, had dominated Prussian and German strategy during the wars of Unification even though the circumstances and internal structures were even more confusing than during the First World War. It was not the result of a faulty constitution or political structures alone that resulted in Germany's defeat; individuals mattered as well. The Empire's structures were complicated and required a skilful and determined leader to function properly. During the First World War, the Reich lacked such a figure.The Power Centres

The Kaiser and His Entourage, Especially the Military, Naval, and Civil Cabinet

The Kaiser was, according to the constitution, the wartime leader of the armed forces of Imperial Germany, and responsible for the coordination of military and civilian efforts of warfare. It was up to him to develop a coherent strategy. Wilhelm II was incapable of performing that task. Historians have examined his personality and intentions, among them his plan to make Germany a global power, in great detail.11 But what matters here was that the Kaiser was a volatile, undisciplined individual, who failed to live up to his constitutional task to coordinate German strategy. Probably even Bismarck would have struggled to control the military and political conduct of this war; but the Kaiser was particularly inept. The head of his military cabinet, General von Lyncker, who part of the emperor's daily entourage, observed in May 1917 that: “He is not equal to this great challenge, having neither the nerve nor the intellect to tackle it.”12 That left a crucial void in the making of German strategy that Wilhelm II refused to allow anyone else to fill. Yet, it was impossible to ignore him. In spite of his erratic personality, he remained a dominant personality who refused to allow others to push him aside. He was therefore half an obstacle and irritant, and half a coordinator of German strategy. In some cases, he participated in the decision-making process with reasonable, but in many other cases his decisions were truly terrible.The Kaiser blustered in peacetime that he would be, if needed, his own chief of staff; but he was unable to lead. He was self-aware enough to realize his shortcomings as a leader, which often kept him from event trying to grab the reins. This restraint was wise but surely frustrating. During the war, he was with the army command in GHQ and was briefed daily by the chief of staff, but not in a way which offered or allowed him active involvement. The Kaiser often complained that he was not even being kept up to date. On 6 November 1914, he made a semi-ironic comment to the chief of the naval cabinet, Admiral von Mueller, that has cemented the image of Wilhelm as a powerless commander-in-chief: “The general staff tells me nothing and does not even consult me. If people in Germany imagine that I command the army, they are much mistaken. I drink tea and chop wood and like to go for walks, and from time to time I find out what has been done, just as it pleases the gentlemen.”13 His complaints were a permanent feature: he was often bad-tempered and argued “that he is being completely side-lined by the chief of staff and that he does not find out anything. He complains that he is expected just to say ‘yes’ to everything and says he could do that just as well from Berlin!”14 - eBook - PDF

Shaping Strategy

The Civil-Military Politics of Strategic Assessment

- Risa Brooks(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

180 C H A P T E R F I V E war allusion, and militarism. Scholars in this tradition also almost univer-sally emphasize the confused and idiosyncratic nature of assessment in Ger-many during the July crisis. Two themes emerge within the historical literature that might account for these weaknesses in Germany's evaluative processes. The first is that Germany's constitutional structure and political institutions predisposed it to poor strategic assessment by supplying so many decision-making pre-rogatives to the kaiser; the system was prone to break down because it vested so much responsibility in one person who could not possibly manage a task of such magnitude (Herwig 1988: 81-82; Mombauer 2001: 14-34; Deist 1982). Yet what this explanation neglects is that the same constitu-tional structure operated quite differently under Wilhelm I I than it had under his predecessor, Wilhelm I , when Bismarck was the kaiser's chancel-lor (Craig 1955: 213-15, 226-29; Ritter 1970: 120). A second theme in the literature suggests one reason why the deficiencies may have been more pronounced under Wilhelm II: the kaiser's personal-ity and psychological state (Mommsen, 1990). Wilhelm I I in fact has been the subject of considerable psychological profiling. 65 Hence Kohut (1982) argues that the kaiser's relationship with his parents promoted a distorted view of foreign policy issues, such as relations with Britain. Hull (1982) contends that Wilhelm II's military and civilian entourage shaped his policy preferences and encouraged his promilitary affectations. However, as historian Richard Evans notes, while intriguing, links between these psy-chological portraits and the policymaking process are underspecified and do not adequately account for the country's strategic choices (1983: 488). 66 More broadly, individual psychology is at best an incomplete explanation for the Wilhelmine case. - eBook - PDF

Export Empire

German Soft Power in Southeastern Europe, 1890–1945

- Stephen G. Gross(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Part I German power in the Wilhelmine Empire and the Weimar Republic 1 The legacy of Wilhelmine imperialism and the First World War, 1890–1920 The Germans excel in the sedulous adaptation of their manufactures to local needs, high and low. They are quick to take account of differences in climate, of taste and custom, and even superstition . . . And with equal patience they get to know enough of the business affairs of individual traders to be able to sell with relatively small risk on long credit, where Englishmen sometimes demand prompt payment. In all this they are much aided by their industry in acquiring languages of Eastern Europe, Asia, and South America. Even in markets in which English is spoken they push their way by taking trouble in small things to which the Englishman will not always bend. 1 Before 1914 the empires of Europe governed nearly two-thirds of the world’s population. These empires differed vastly from one another: Britain’s multifaceted imperial system with its dominions and its crown jewel of India seemed a world apart from Portugal’s maritime posses- sions or the vast Eurasian land imperium of Russia. And these empires had changed over the course of the long nineteenth century, as Euro- peans carried out wave after wave of territorial annexation in Africa and Southeast Asia, and as they presided over an explosion of global trade, international investment, and migration that connected imperial cores and peripheries in ever denser webs of entanglement. By the early twen- tieth century, across much of the globe imperial rule of one form or another was the norm rather than the exception. 2 Germans came late to the struggle for empire. Even after Prussia uni- fied Germany in 1871 relatively few intellectuals or politicians displayed serious interest in acquiring overseas colonies or expanding German ter- ritory within Europe. - eBook - PDF

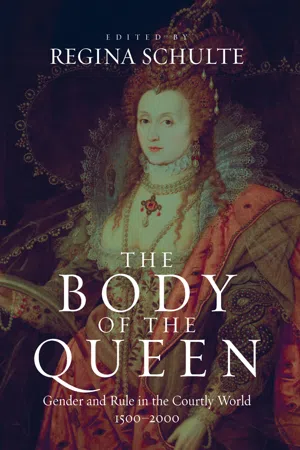

The Body of the Queen

Gender and Rule in the Courtly World, 1500-2000

- Regina Schulte(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Berghahn Books(Publisher)

After he ascended the throne, a wave of laudatory newspaper articles and pamphlets appeared. All of them made much of the emperor’s youth. Also prominent was the emphasis on Wilhelm’s ‘character’ and individualism. 8 The individuality of the monarch and the cult of the young emperor were closely related. As Stefan Breuer has noted, there was a strong tendency within Wilhelminism ‘to stage the struggle for symbolic power as an intergenerational drama’. 9 This was particularly true of the highly sensitised Jüngstdeutsche (youngest or most recent German, a reference to the Young German movement of the 1830s) writers, for whom the purported individuality of the young emperor appeared significant to the extent that they viewed it as the most outstanding trait of their own generation. One of these authors, Konrad Alberti (the pseudonym of The Unmanly Emperor: Wilhelm II 255 K. Sittenfeld, 1862–1918), confronted the emperor with the expectations of the young generation immediately following his coronation, addressing Wilhelm II as a member of that generation. 10 Hermann Conradi (1862–90) did likewise in his Wilhelm II. und die junge Generation. Eine zeitpsychologische Betrachtung (Wilhelm II and the Young Generation. A Contemporary Psychological Perspective). 11 This went beyond merely equating the young generation with the youthful emperor; individualism functioned as a key concept here. In the ‘historically powerful’ year of 1888 Germany had ‘experienced its true Storm and Stress’; ‘a young emperor had ascended the throne, having scarcely had a chance to warm up as a crown prince, who had matured in the sultry hothouse air of compact, confused troubles and fears, and to whom anybody would have to reorganise the angle of his personal relationship, which had so recently been directed and orientated towards Kaiser Friedrich’, Conradi wrote.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.