Mathematics

Central Limit Theorem

The Central Limit Theorem states that the sampling distribution of the sample mean will be approximately normally distributed, regardless of the shape of the original population distribution, as long as the sample size is sufficiently large. This theorem is a fundamental concept in statistics and is widely used in making inferences about population parameters based on sample data.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Central Limit Theorem"

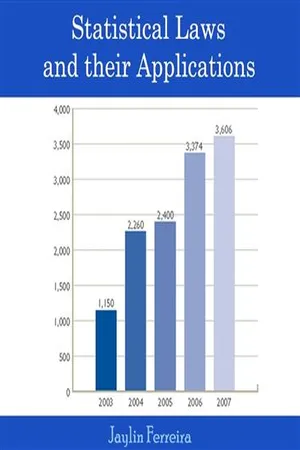

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Orange Apple(Publisher)

In more general probability theory, a Central Limit Theorem is any of a set of weak-convergence theories. They all express the fact that a sum of many independent random variables will tend to be distributed according to one of a small set of attractor (i.e. stable) distributions. When the variance of the variables is finite, the attractor distribution is the normal distribution. Specifically, the sum of a number of random variables with power law tail distributions decreasing as 1/|x| α + 1 where 0 < α < 2 (and therefore having infinite variance) will tend to a stable distribution with stability parameter (or index of stability) of α as the number of variables grows. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Classical Central Limit Theorem A distribution being smoothed out by summation, showing original density of distribution and three subsequent summations. The Central Limit Theorem is also known as the second fundamental theorem of probability. (The Law of large numbers is the first.) Let X 1 , X 2 , X 3 , …, X n be a sequence of n independent and identically distributed (iid) random variables each having finite values of expectation µ and variance σ 2 > 0. The Central Limit Theorem states that as the sample size n increases, the distribution of the sample average of these random variables approaches the normal distribution with a mean µ and variance σ 2 /n irrespective of the shape of the common distribution of the individual terms X i . For a more precise statement of the theorem, let S n be the sum of the n random variables, given by Then, if we define new random variables ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ then they will converge in distribution to the standard normal distribution N(0,1) as n approaches infinity. N(0,1) is thus the asymptotic distribution of the Z n 's. This is often written as Z n can also be expressed as where is the sample mean. - eBook - PDF

- Vladimir I. Rotar(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Chapman and Hall/CRC(Publisher)

Chapter 9 The Central Limit Theorem for Independent Random Variables 1,2 1 THE Central Limit Theorem FOR I.I.D. RANDOM VARIABLES 1.1 A theorem and examples Loosely put, the Central Limit Theorem (CLT) says that the distribution of the sum of a large number of independent r.v.’s is close to a normal distribution. In the case of identically distributed r.v.’s, this may be stated as follows. Consider a sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) r.v.’s X 1 , X 2 , ... with finite variances and set S n = X 1 + ... + X n . Let m = E { X i } and σ 2 = Var { X i } . Then E { S n } = mn , Var { S n } = σ 2 n . We normalize S n and consider the r.v. S ∗ n = S n − E { S n } Var { S n } = S n − mn σ √ n . It is noteworthy that the normalized r.v. S ∗ n may be viewed as the same sum S n considered in an appropriate scale: after the normalization, E { S ∗ n } = 0, and Var { S ∗ n } = 1 (for detail, see Section 6 .1.5). Theorem 1 (The Central Limit Theorem). For any ( fi nite or in fi nite) a and b ≥ a, P ( a ≤ S ∗ n ≤ b ) → Φ ( b ) − Φ ( a ) = 1 √ 2 π b a e − x 2 / 2 dx as n → ∞ , (1.1.1) where Φ ( x ) = 1 √ 2 π x − ∞ e − u 2 / 2 du, the standard normal distribution function. In particular, for any x, P ( S ∗ n ≤ x ) → Φ ( x ) as n → ∞ . (1.1.2) A proof will be considered in Section 1.2. In spite of its simple statement, the CLT deals with a deep and important fact. The theorem says that as the number of the terms in the sum S n is getting larger, the influence of separate terms is diminishing and the distribution of S n is getting close to a standard distribution (namely, normal) regardless of which distribution the separate terms have. It may be continuous or discrete, or neither of these, uniform, exponential, binomial, or anything else—provided that the variance of the terms is finite, the distribution of the sum S n for large n may be well approximated by a normal distribution. 249 - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Library Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 6 Central Limit Theorem Histogram plot of average proportion of heads in a fair coin toss, over a large number of sequences of coin tosses In probability theory, the Central Limit Theorem ( CLT ) states conditions under which the mean of a sufficiently large number of independent random variables, each with finite mean and variance, will be approximately normally distributed (Rice 1995). The Central Limit Theorem also requires the random variables to be identically distributed, unless certain conditions are met. Since real-world quantities are often the balanced sum of many unobserved random events, this theorem provides a partial explanation for the prevalence of the normal probability distribution. The CLT also justifies the ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ approximation of large-sample statistics to the normal distribution in controlled experiments. A simple example of the Central Limit Theorem is given by the problem of rolling a large number of dice, each of which is weighted unfairly in some unknown way. The distribution of the sum (or average) of the rolled numbers will be well approximated by a normal distribution, the parameters of which can be determined empirically. In more general probability theory, a Central Limit Theorem is any of a set of weak-convergence theories. They all express the fact that a sum of many independent random variables will tend to be distributed according to one of a small set of attractor (i.e. stable) distributions. When the variance of the variables is finite, the attractor distribution is the normal distribution. Specifically, the sum of a number of random variables with power law tail distributions decreasing as 1/|x| α + 1 where 0 < α < 2 (and therefore having infinite variance) will tend to a stable distribution with stability parameter (or index of stability) of α as the number of variables grows. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 1 Central Limit Theorem Histogram plot of average proportion of heads in a fair coin toss, over a large number of sequences of coin tosses In probability theory, the Central Limit Theorem ( CLT ) states conditions under which the mean of a sufficiently large number of independent random variables, each with finite mean and variance, will be approximately normally distributed (Rice 1995). The Central Limit Theorem also requires the random variables to be identically distributed, unless certain conditions are met. Since real-world quantities are often the balanced sum of many unobserved random events, this theorem provides a partial explanation for the prevalence of the normal probability distribution. The CLT also justifies the appro-ximation of large-sample statistics to the normal distribution in controlled experiments. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ A simple example of the Central Limit Theorem is given by the problem of rolling a large number of dice, each of which is weighted unfairly in some unknown way. The distribution of the sum (or average) of the rolled numbers will be well approximated by a normal distribution, the parameters of which can be determined empirically. In more general probability theory, a Central Limit Theorem is any of a set of weak-convergence theories. They all express the fact that a sum of many independent random variables will tend to be distributed according to one of a small set of attractor (i.e. stable) distributions. When the variance of the variables is finite, the attractor distribution is the normal distribution. Specifically, the sum of a number of random variables with power law tail distributions decreasing as 1/| x | α + 1 where 0 < α < 2 (and therefore having infinite variance) will tend to a stable distribution with stability parameter (or index of stability) of α as the number of variables grows. - eBook - ePub

- Dov M. Gabbay, Paul Thagard, John Woods(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- North Holland(Publisher)

In practice, the primary use of the CLT is to approximate the sampling distribution of a test statistic or the sampling distribution of an asymptotically pivotal quantity. It is frequentists rather than Bayesians who use sampling distributions to make inferences about parameter values. Accordingly, the applications in 4.2, 5.2 and 8 are frequentist in nature. For example, a frequentist who is interested in the value of a population mean, μ, might obtain a random sample, Y 1, Y 2,…, Y n, from the population and use the CLT to approximate the sampling distribution of the sample mean. The approximate sampling distribution of then could be used to construct a confidence interval for μ. A Bayesian who is interested in a population mean, μ would adopt a different approach. The Bayesian would treat μ as a random variable, rather than as a fixed quantity. Inference about μ would be based on the distribution of μ conditional on the data, Y 1, Y 2,…, Y n. This conditional distribution is called the posterior distribution. Conditional distributions are defined in Appendix A.1. Section 7 describes a Bayesian CLT for posterior distributions. The last section describes higher-order expansions that improve on the accuracy of frequentist and Bayesian CLTs. 2. The Central Limit Theorem The normal distribution with mean μ and variance σ 2 is denoted by N(μ, σ 2). Its probability density function (pdf) is (1) A random variable Z with distribution N(0,1) is said to have the standard normal distribution. The pdf of the standard normal distribution is φ (z,0,1) and, for convenience, this pdf is denoted simply as φ (z). The normal distribution also is called the “Gaussian” distribution in honor of K.F. Gauss, even though Gauss was not the first to use this distribution. Nonetheless, it was Gauss, [1809] who discovered the intimate connections between the normal distribution and the method of least squares - eBook - ePub

A Panorama of Statistics

Perspectives, Puzzles and Paradoxes in Statistics

- Eric Sowey, Peter Petocz(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

If you were to become addicted to roulette, you might, over many years, play this game a very large number of times. In that case, to work out the chance of coming out ahead at the end, it will be arithmetically simpler to move away from the binomial distribution and invoke the Central Limit Theorem (CLT), one of the most important theorems in statistics.‐‐‐oOo‐‐‐At its most basic, the CLT says that if you draw a sample randomly from a population that is not normally distributed, the sample mean will nevertheless be approximately normally distributed, and the approximation will improve as the sample size increases.To bring out its significance, let’s amplify four aspects of this statement:- First aspect: the CLT is about the distribution of the mean of a random sample from a non‐normal population. What is meant by ‘the distribution of the sample mean’? This is a shorthand expression for a more wordy notional concept – ‘the distribution of the means of all possible samples of a fixed size, drawn from the population’. The technical term for this concept is ‘the sampling distribution of the mean’.

- Second aspect: the CLT is about the distribution of the mean of a random sample from a non‐normal population. Which non‐normal population? The CLT applies to unimodal non‐normal populations, whether symmetric or non‐symmetric. It even applies to bimodal populations. And – using a mathematical method to match up discrete and continuous probabilities – it applies to discrete populations (such as the binomial), not just to continuous populations. Finally, it applies to empirical populations (comprising data values collected in the real world) as well as to theoretical populations (such as the binomial).

- Third aspect: the CLT says that the mean of a random sample from a non‐normal population will be approximately normally distributed (this behaviour is sometimes called ‘the CLT effect’). Does the CLT effect appear in the distribution of the sample mean from all populations of the kinds just listed? No – there are some theoretical populations for which the CLT effect is absent. There are examples of such populations in CHAPTER 24. A useful guide is this: if the population has a finite variance then the CLT applies. That is why the CLT certainly applies to all empirical

- eBook - PDF

Stochastics

Introduction to Probability and Statistics

- Hans-Otto Georgii, Marcel Ortgiese, Ellen Baake, Hans-Otto Georgii, Marcel Ortgiese, Ellen Baake, Hans-Otto Georgii(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

5 The Law of Large Numbers and the Central Limit Theorem In this chapter we discuss two fundamental limit theorems for long-term averages of independent, identically distributed real-valued random variables. The fi rst theorem is the law of large numbers, which is about the convergence of the averages to the common expectation. Depending on the notion of convergence, one distinguishes between the weak and the strong law of large numbers. The second theorem, the Central Limit Theorem, describes how far the averages typically deviate from their expectation in the long run. It is here that the universal importance of the normal distribution is revealed. 5.1 The Law of Large Numbers 5.1.1 The Weak Law of Large Numbers Our experience shows: If we perform n independent, but otherwise identical exper-iments, for example measurements in physics, and if we denote by X i the result of the i th experiment, then for large n the average 1 n ∑ n i = 1 X i is very close to a fi xed number. Intuitively, we would like to call this number the expectation of the X i . This experience serves also as a justi fi cation for the interpretation of probabilities as relative frequencies, which states that P ( A ) ≈ 1 n n i = 1 1 { X i ∈ A } . In words: The probability of an event A coincides with the relative frequency of occurrences of A , provided we perform a large number of independent, identically distributed observations X 1 , . . . , X n . Does our mathematical model re fl ect this experience? To answer this, we fi rst have to deal with the question: In which sense can we expect convergence to the mean? The next example shows that, even after a long time, exact agreement of the average and the expectation will only happen with a negligible probability. Let us fi rst recall a fact from analysis (see for example [18, 53]), known as Stirling’s formula : (5.1) n ! = √ 2 π n n n e − n + η( n ) with 0 < η( n ) < 1 12 n . - eBook - PDF

- Alan M. Polansky(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Chapman and Hall/CRC(Publisher)

CHAPTER 6 Central Limit Theorems They formed a unit of the sort that normally can be formed only by matter that is lifeless. The Trial by Franz Kafka 6.1 Introduction One of the important and interesting features of the Central Limit Theorem is that the weak convergence of the mean holds under many situations beyond the simple situation where we observe a sequence of independent and iden-tically distributed random variables. In this chapter we will explore some of these extensions. The two main direct extensions of the Central Limit Theo-rem we will consider are to non-identically distributed random variables and to triangular arrays. Of course, other generalizations are possible, and we only present some of the simpler cases. For a more general presentation of this subject see Gnedenko and Kolmogorov (1968). We will also consider transfor-mations of asymptotically normal statistics that either result in asymptoti-cally Normal statistics, or statistics that follow a ChiSquared distribution. As we will show, the difference between these two outcomes depends on the smoothness of the transformation. 6.2 Non-Identically Distributed Random Variables The Lindeberg, L´ evy, and Feller version of the Central Limit Theorem relaxes the assumption that the random variables in the sequence need to be identi-cally distributed, but still retains the assumption of independence. The result originates from the work of Lindeberg (1922), L´ evy (1925), and Feller (1935), who each proved various parts of the final result. Theorem 6.1 (Lindeberg, L´ evy, and Feller) . Let { X n } ∞ n =1 be a sequence of independent random variables where E ( X n ) = μ n and V ( X n ) = σ 2 n < ∞ for all n ∈ N where { μ n } ∞ n =1 and { σ 2 n } ∞ n =1 are sequences of real numbers. Let ¯ μ n = n -1 n X k =1 μ k , 255 - eBook - ePub

- Deborah J. Rumsey(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- For Dummies(Publisher)

— if the sample size is large enough. This momentous result is due to what statisticians know and love as the Central Limit Theorem.The Central Limit Theorem (abbreviated CLT ) says that if X does not have a normal distribution (or its distribution is unknown and hence can’t be deemed to be normal), the shape of the sampling distribution of is approximately normal, as long as the sample size, n, is large enough. That is, you get an approximate normal distribution for the means of large samples, even if the distribution of the original values (X ) is not normal.Most statisticians agree that if n is at least 30, this approximation will be reasonably close in most cases, although different distribution shapes for X have different values of n that are needed. The larger the sample size (n ), the closer the distribution of the sample means will be to a normal distribution.Averaging a fair die is approximately normal

Consider the die rolling example from the earlier section “Defining a Sampling Distribution .” Notice in Figure 11-1a , the distribution of X (the population of outcomes based on millions of single rolls) is flat; the individual outcomes of each roll go from 1 to 6, and each outcome is equally likely.Things change when you look at averages. When you roll a die a large number of times (say a sample of 50 times) and look at your outcomes, you’ll probably find about the same number of 6s as 1s (note that 6 and 1 average out to 3.5); 5s as 2s (5 and 2 also average out to 3.5); and 4s as 3s (which also average out to 3.5 — do you see a pattern here?). So if you roll a die 50 times, you have a high probability of getting an overall average that’s close to 3.5. Sometimes just by chance things won’t even out as well, but that won’t happen very often with 50 rolls.Getting an average at the extremes with 50 rolls is a very rare event. To get an average of 1 on 50 rolls, you need all 50 rolls to be 1. How likely is that? (If it happens to you, buy a lottery ticket right away, it’s the luckiest day of your life!) The same is true for getting an average near 6. - eBook - PDF

- Deborah J. Rumsey(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- For Dummies(Publisher)

If you refer to the other curves in Figure 12-2, you see the average times for samples of n 10 and n 50 clerical workers, respectively, also have normal distributions. When X has a normal distribution, the sample means also always have a normal distribution, no matter what size samples you take, even if you take samples of only two clerical workers at a time. The difference between the curves in Figure 12-2 is not their means or their shapes, but rather their amount of variability (how close the values in the distribution are to the mean). Results based on large samples vary less and will be more concentrated around the mean than results from small samples or results from the individuals in the population. Case 2: The distribution of X is not normal — Enter the Central Limit Theorem If X has any distribution that is not normal, or if its distribution is unknown, you can’t auto- matically say the sample mean ( ) X has a normal distribution. But incredibly, you can use a normal distribution to approximate the distribution of X — if the sample size is large enough. This momentous result is due to what statisticians know and love as the Central Limit Theorem. The Central Limit Theorem (abbreviated CLT) says that if X does not have a normal distribution (or its distribution is unknown and hence can’t be deemed to be normal), the shape of the sam- pling distribution of X is approximately normal, as long as the sample size, n, is large enough. That is, you get an approximate normal distribution for the means of large samples, even if the distribution of the original values (X) is not normal. 270 UNIT 3 Distributions and the Central Limit Theorem Most statisticians agree that if n is at least 30, this approximation will be reasonably close in most cases, although different distribution shapes for X have different values of n that are needed. The larger the sample size (n), the closer the distribution of the sample means will be to a normal distribution. - eBook - PDF

Introduction to Probability

Multivariate Models and Applications

- Narayanaswamy Balakrishnan, Markos V. Koutras, Konstadinos G. Politis(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

KEY TERMS 507 KEY TERMS Central Limit Theorem (CLT) convergence almost surely (or with probability 1) convergence in distribution convergence in mean convergence in probability convergence in r-th mean convergence in quadratic mean (or in mean square) empirical distribution function Lévy–Cramer continuity theorem Stirling formula strong law of large numbers (SLLN) weak law of large numbers (WLLN) APPENDIX A TAIL PROBABILITY UNDER STANDARD NORMAL DISTRIBUTION a z 0.00 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.07 0.08 0.09 0.0 0.5000 0.4960 0.4920 0.4880 0.4840 0.4801 0.4761 0.4721 0.4681 0.4641 0.1 0.4602 0.4562 0.4522 0.4483 0.4443 0.4404 0.4364 0.4325 0.4286 0.4247 0.2 0.4207 0.4168 0.4129 0.4090 0.4052 0.4013 0.3974 0.3936 0.3897 0.3859 0.3 0.3821 0.3783 0.3745 0.3707 0.3669 0.3632 0.3594 0.3557 0.3520 0.3483 0.4 0.3446 0.3409 0.3372 0.3336 0.3300 0.3264 0.3228 0.3192 0.3156 0.3121 0.5 0.3085 0.3050 0.3015 0.2981 0.2946 0.2912 0.2877 0.2843 0.2810 0.2776 0.6 0.2743 0.2709 0.2676 0.2643 0.2611 0.2578 0.2546 0.2514 0.2483 0.2451 0.7 0.2420 0.2389 0.2358 0.2327 0.2297 0.2266 0.2231 0.2206 0.2177 0.2148 0.8 0.2119 0.2090 0.2061 0.2033 0.2005 0.1977 0.1949 0.1922 0.1984 0.1867 0.9 0.1841 0.1814 0.1788 0.1762 0.1736 0.1711 0.1685 0.1660 0.1635 0.1611 1.0 0.1587 0.1562 0.1539 0.1515 0.1492 0.1469 0.1446 0.1423 0.1401 0.1379 1.1 0.1357 0.1335 0.1314 0.1292 0.1271 0.1251 0.1230 0.1210 0.1190 0.1170 1.2 0.1151 0.1131 0.1112 0.1093 0.1075 0.1056 0.1038 0.1020 0.1003 0.0985 1.3 0.0968 0.0951 0.0934 0.0918 0.0901 0.0885 0.0869 0.0853 0.0838 0.0823 1.4 0.0808 0.0793 0.0778 0.0764 0.0749 0.0735 0.0721 0.0708 0.0694 0.0681 1.5 0.0668 0.0655 0.0643 0.0630 0.0618 0.0606 0.0594 0.0582 0.0571 0.0559 1.6 0.0548 0.0537 0.0526 0.0516 0.0505 0.0495 0.0485 0.0475 0.0465 0.0455 1.7 0.0446 0.0436 0.0427 0.0418 0.0409 0.0401 0.0392 0.0384 0.0375 0.0367 509 Introduction to Probability: Multivariate Models and Applications, Volume 2, First Edition. N. Balakrishnan, Markos V. Koutras, and Konstadinos G. - eBook - ePub

Resonance: From Probability To Epistemology And Back

From Probability to Epistemology and Back

- Krzysztof Burdzy(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- ICP(Publisher)

The methods of generating predictions from confidence intervals outlined above may be hard to implement in practice for multiple reasons. It is best to discuss some of the most obvious challenges rather than to try to sweep the potential problems under the rug.Generating a prediction from a single confidence interval requires very solid knowledge of the tails of the distribution of the random variable used to construct the confidence interval. If the random variable in question is, for example, the average of an i.i.d. sequence, then the Central Limit Theorem becomes questionable as an appropriate mathematical tool for the analysis of the tails. We enter the domain of the Large Deviations Principle (see Sec. 18.1.1 ). On the theoretical side, typically, it is harder to prove a theorem that has the form of a Large Deviations Principle than a version of the Central Limit Theorem. On the practical side, the Large Deviations Principle-type results require stronger assumptions than the Law of Large Numbers or the Central Limit Theorem — checking or guessing whether these assumptions hold in practice might be a tall order.Only in some situations, we can assume that individual statistical problems that form an aggregate are approximately independent. Without independence, generating a prediction based on an aggregate of many cases of statistical analysis can be very challenging.Expressing losses due to errors in monetary terms may be hard or subjective. If the value of a physical quantity is commonly used by scientists around the world, it is not an easy task to assess the combined losses due to non-coverage of the true value by a confidence interval. At the other extreme, if the statistical analysis of a scientific quantity appears in a specialized journal and is never used directly in real life, the loss due to a statistical error has a purely theoretical nature and is hard to express in monetary terms.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.