Physics

Escape Velocity

Escape velocity is the minimum speed an object must reach to break free from the gravitational pull of a celestial body, such as a planet or a star. It is the velocity required for an object to escape the gravitational influence without any additional propulsion. The concept is crucial for understanding space travel and the dynamics of celestial bodies.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

5 Key excerpts on "Escape Velocity"

- eBook - PDF

- Michael Seeds, Dana Backman(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

An astro-naut who appears weightless in space is actually falling along a path at the urging of the combined gravitational fields of the rest of the Universe. Just above Earth’s atmosphere, the orbital motion of the astronaut is almost completely due to Earth’s gravity. Calculating Escape Velocity If you launch a rocket upward, it will consume its fuel in a few moments and reach its maximum speed. From that point on, it will coast upward. How fast must a rocket travel to coast away from Earth and escape? Of course, no matter how far it travels, it can never escape from Earth’s gravity. The effects of Earth’s gravity (and the gravity of all other objects) extend to infinity. It is possible, however, for a rocket to travel so fast initially that gravity can never slow it to a stop. Then the rocket could leave Earth permanently. Escape Velocity is the velocity required to escape an astro-nomical body. Here you are interested in escaping from the surface of Earth; in later chapters you will consider the Escape Velocity from other planets, the Sun, stars, galaxies, and even black holes. Escape Velocity, V e , is given by a simple formula: V e 5 2 GM r Again, G is the gravitational constant, 6.67 3 10 2 11 m 3 /s 2 /kg, M is the mass of the central body in kilograms, and r is its radius in meters. - eBook - PDF

From Atoms to Galaxies

A Conceptual Physics Approach to Scientific Awareness

- Sadri Hassani(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Taking the square root, and calling this smallest velocity the Escape Velocity , we have v esc = p 2 GM/r . The Escape Velocity usually refers to the Escape Velocity. minimum speed with which a projectile is to be fired at the surface of a spherical celestial body—where r is equal to the radius R of the body—for it never to return. For such a projectile, we obtain v esc = r 2 GM R . (9.8) Section 9.2 Gravitational Field and Potential Energy 143 Example 9.2.4. By substituting the mass and the radius of the Earth in Equation (9.8) we can find the Escape Velocity of Earth. It turns out to be about 11 km/s. Similarly, the Escape Velocity of the Moon can be calculated. It is about 2 km/s. Example D.9.9 on page 31 of Appendix.pdf explains how we got these numbers. One of the reasons that the Moon has no atmosphere is because of its low Escape Velocity. The average thermal molecular speed of most gases is comparable to the Escape Velocity of the Moon. Therefore, in their constant random motion, they will eventually move away from the Moon, and never return. What do you know? 9.9. Inflate the Earth by a factor of a million, so that the inflated Earth has radius one million times larger than the present Earth. What would be the Escape Velocity at the surface of the inflated Earth? If you throw a ball as hard as you can, will it escape the inflated Earth? Example 9.2.5. A satellite is circling at a certain distance from a planet. 3 From Equation (9.3), the velocity and KE of the satellite can be calculated. You can also find the potential energy of the satellite. Now add them and find that the total energy of the satellite is negative . This is a characteristic of a bound system : the satellite is bound to the planet, and cannot A bound system and its binding energy. escape from it (without the injection of some energy from outside). - eBook - PDF

- William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff Sanny(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

For this reason, many commercial space companies maintain launch facilities near the equator. To escape the Sun, there is even more help. Earth revolves about the Sun at a speed of approximately 30 km/s. By launching in the direction that Earth is moving, we need only an additional 12 km/s. The use of gravitational assist from other planets, essentially a gravity slingshot technique, allows space probes to reach even greater speeds. In this slingshot technique, the vehicle approaches the planet and is accelerated by the planet’s gravitational attraction. It has its greatest speed at the closest point of approach, although it decelerates in equal measure as it moves away. But relative to the planet, the vehicle’s speed far before the approach, and long after, are the same. If the directions are chosen correctly, that can result in a significant increase (or decrease if needed) in the vehicle’s speed relative to the rest of the solar system. Visit this website (https://openstaxcollege.org/l/21escapevelocit) to learn more about Escape Velocity. Check Your Understanding If we send a probe out of the solar system starting from Earth’s surface, do we only have to escape the Sun? Energy and gravitationally bound objects As stated previously, Escape Velocity can be defined as the initial velocity of an object that can escape the surface of a moon or planet. More generally, it is the speed at any position such that the total energy is zero. If the total energy is zero or greater, the object escapes. If the total energy is negative, the object cannot escape. Let’s see why that is the case. As noted earlier, we see that U → 0 as r → ∞ . If the total energy is zero, then as m reaches a value of r that approaches infinity, U becomes zero and so must the kinetic energy. Hence, m comes to rest infinitely far away from M. It has “just escaped” M. If the total energy is positive, then kinetic energy remains at r = ∞ and certainly m does not return. - Joseph C. Amato, Enrique J. Galvez(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

A spacecraft launched with the Escape Velocity v E given by Equation 10.7 will escape from Earth, but will still be trapped within the solar system because of its attrac -tion to the Sun. (a) Imagine a spacecraft that has escaped from Earth and is coasting in an Earth-leading circular orbit of radius 1 AU. Write an expression for the minimum speed vs. (relative to the Sun) that the spacecraft must attain to escape the Sun. (Ignore the force due to Earth.) Calculate this speed. (b) Now consider the spacecraft before launch. Write the potential energy Chapter 10 – Gravitational Potential Energy and Orbital Motion 421 function associated with the rocket– Earth and rocket–Sun interactions. Then write an equation akin to Equation 10.6 for the total energy after launch. (c) Show from your equation that the launch speed needed to escape the Earth and Sun is given by v v v L E S 2 2 2 = + . Find a numerical value for v L . (d) Qualitatively compare the fuel required at launch to escape the Sun rather than to escape the Earth? 10.24 Europa , the smallest of the four Galilean moons of Jupiter, is thought to have an icy surface capping an underground ocean of liquid water. Europa is a prime suspect in the search for extraterrestrial life and will be visited by an ESA (European Space Agency) space probe scheduled for launch in 2022. Europa has a mass of 4.8 × 10 22 kg, a radius of 1565 km, and a surface tempera -ture of 122 K. The figure shows the moon’s smooth surface crisscrossed by cracks in the ice. (Photo courtesy of Ted Stryk NASA/JPL.) (a) What is the value of “ g ” on the surface of Europa? What is the Escape Velocity from its surface? (b) Using Figure 10.6 , make a statement about the composition of Europa’s atmo -sphere. Observations from the Hubble space telescope and the Galileo space probe indicate that the atmosphere is mostly O 2 . How do you account for this? 10.25 Most of the matter in the universe is invisi -ble.- Available until 25 Jan |Learn more

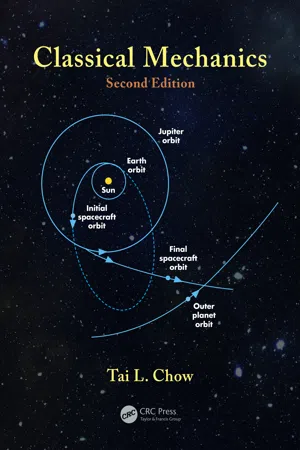

- Tai L. Chow(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

179 Motion Under a Central Force © 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC 6.7.3 F LYBY M ISSIONS TO O UTER P LANETS Flyby missions to the outer planets provide another interesting practical application of the inverse square theory. The energy requirements would be far beyond the capabilities of rocket technology today if it were not possible to utilize gravity boost along the way. We first estimate the minimum launch speed from the Earth for a spacecraft getting into orbit to an outer planet. For a spacecraft of mass m at distance r from the sun to completely escape the sun’s gravitational pull, the minimum launch speed is given by E mV GmM r s = = -0 2 2 esp . (6.57) Solving for V esp , we find V GM r s esp / k m/s = = 2 4 2 where r is the distance of the Earth from the sun, and M s is the sun’s mass. However, if the launch is made in the direction of the Earth’s orbital speed about the sun (Figure 6.15), the minimum launch speed for getting into orbit can be reduced significantly. The Earth’s orbital speed V e can be deter-mined by equating centripetal and gravitational force: GmM r m V r s e / / 2 2 = from which we find V GM r V e s = = = / k m/s esp 1 2 30 . Thus, by making the launch in the direction of Earth’s orbital velocity, the initial velocity required for escape from the sun’s gravitational pull can be reduced to 12 km/s. Note that the spacecraft must have additional initial velocity to escape from the Earth’s gravitational pull. Moreover, the launch must be so timed that the spacecraft and the outer planet will meet at aphelion on the spacecraft Spacecraft Earth Sun Outer planet FIGURE 6.15 Flyby missions to the outer planets. 180 Classical Mechanics © 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC orbit as illustrated in Figure 6.16. The orbit of the spacecraft is an elliptical one about the sun with perihelion at the Earth’s orbit, and the planet and the spacecraft meet at the aphelion.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.