Physics

Orbital Trajectory

An orbital trajectory refers to the path followed by an object as it moves around another object in space, typically under the influence of gravity. This trajectory can be elliptical, circular, or parabolic, depending on the initial conditions and the forces acting on the object. Understanding orbital trajectories is crucial for space missions, satellite deployment, and celestial mechanics.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Orbital Trajectory"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 7 Orbit Two bodies of different mass orbiting a common barycenter. The relative sizes and type of orbit are similar to the Pluto–Charon system. In physics, an orbit is the gravitationally curved path of an object around a point in space, for example the orbit of a planet around the center of a star system, such as the solar system. Orbits of planets are typically elliptical. Current understanding of the mechanics of orbital motion is based on Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, which accounts for gravity as due to curvature of space-time, with orbits following geodesics; though in common practice an approximate force-based theory of universal gravitation based on Kepler's laws of planetary motion is often used instead for ease of calculation. History Historically, the apparent motions of the planets were first understood geometrically (and without regard to gravity) in terms of epicycles, which are the sums of numerous circular motions. Theories of this kind predicted paths of the planets moderately well, until Johannes Kepler was able to show that the motions of planets were in fact (at least approximately) elliptical motions. In the geocentric model of the solar system, the celestial spheres model was originally used to explain the apparent motion of the planets in the sky in terms of perfect spheres ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ or rings, but after the planets' motions were more accurately measured, theoretical mechanisms such as deferent and epicycles were added. Although it was capable of accurately predicting the planets' position in the sky, more and more epicycles were required over time, and the model became more and more unwieldy. The basis for the modern understanding of orbits was first formulated by Johannes Kepler whose results are summarised in his three laws of planetary motion. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- College Publishing House(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 10 Orbit Two bodies of different mass orbiting a common barycenter. The relative sizes and type of orbit are similar to the Pluto–Charon system. In physics, an orbit is the gravitationally curved path of an object around a point in space, for example the orbit of a planet around the center of a star system, such as the solar system. Orbits of planets are typically elliptical. Current understanding of the mechanics of orbital motion is based on Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, which accounts for gravity as due to curvature of space-time, with orbits following geodesics; though in common practice an approximate force-based theory of universal gravitation based on Kepler's laws of planetary motion is often used instead for ease of calculation. History Historically, the apparent motions of the planets were first understood geometrically (and without regard to gravity) in terms of epicycles, which are the sums of numerous circular motions. Theories of this kind predicted paths of the planets moderately well, until Johannes Kepler was able to show that the motions of planets were in fact (at least approximately) elliptical motions. In the geocentric model of the solar system, the celestial spheres model was originally used to explain the apparent motion of the planets in the sky in terms of perfect spheres ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ or rings, but after the planets' motions were more accurately measured, theoretical mechanisms such as deferent and epicycles were added. Although it was capable of accurately predicting the planets' position in the sky, more and more epicycles were required over time, and the model became more and more unwieldy. The basis for the modern understanding of orbits was first formulated by Johannes Kepler whose results are summarised in his three laws of planetary motion. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 6 Orbit Two bodies of different mass orbiting a common barycenter. The relative sizes and type of orbit are similar to the Pluto–Charon system. In physics, an orbit is the gravitationally curved path of an object around a point in space, for example the orbit of a planet around the center of a star system, such as the solar system. Orbits of planets are typically elliptical. Current understanding of the mechanics of orbital motion is based on Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, which accounts for gravity as due to curvature of space-time, with orbits following geodesics; though in common practice an approximate force-based theory of universal gravitation based on Kepler's laws of planetary motion is often used instead for ease of calculation. History Historically, the apparent motions of the planets were first understood geometrically (and without regard to gravity) in terms of epicycles, which are the sums of numerous circular motions. Theories of this kind predicted paths of the planets moderately well, until Johannes Kepler was able to show that the motions of planets were in fact (at least approximately) elliptical motions. In the geocentric model of the solar system, the celestial spheres model was originally used to explain the apparent motion of the planets in the sky in terms of perfect spheres ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ or rings, but after the planets' motions were more accurately measured, theoretical mechanisms such as deferent and epicycles were added. Although it was capable of accurately predicting the planets' position in the sky, more and more epicycles were required over time, and the model became more and more unwieldy. The basis for the modern understanding of orbits was first formulated by Johannes Kepler whose results are summarised in his three laws of planetary motion. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- College Publishing House(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 6 Orbit Two bodies of different mass orbiting a common barycenter. The relative sizes and type of orbit are similar to the Pluto–Charon system. In physics, an orbit is the gravitationally curved path of an object around a point in space, for example the orbit of a planet around the center of a star system, such as the solar system. Orbits of planets are typically elliptical. Current understanding of the mechanics of orbital motion is based on Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, which accounts for gravity as due to curvature of space-time, with orbits following geodesics; though in common practice an approximate force-based theory of universal gravitation based on Kepler's laws of planetary motion is often used instead for ease of calculation. History Historically, the apparent motions of the planets were first understood geometrically (and without regard to gravity) in terms of epicycles, which are the sums of numerous circular motions. Theories of this kind predicted paths of the planets moderately well, until Johannes Kepler was able to show that the motions of planets were in fact (at least approximately) elliptical motions. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ In the geocentric model of the solar system, the celestial spheres model was originally used to explain the apparent motion of the planets in the sky in terms of perfect spheres or rings, but after the planets' motions were more accurately measured, theoretical mechanisms such as deferent and epicycles were added. Although it was capable of accurately predicting the planets' position in the sky, more and more epicycles were required over time, and the model became more and more unwieldy. The basis for the modern understanding of orbits was first formulated by Johannes Kepler whose results are summarised in his three laws of planetary motion. - eBook - PDF

- V. I. Feodosiev, G. B. Siniarev(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

The center of gravity of the rocket also receives transverse oscillatory displacements due to the periodic change in the lift force L. The trajectory of the rocket center of gravity, taking into account angular oscillations, appears as shown in Fig. 8.11. As a first approximation, these oscillatory motions may be neglected, which has been done above. C. Flight Beyond the Limits of the Atmosphere Within the Earth's Gravitational Field 1. EQUATIONS OF MOTION The greater part of the trajectory of a long range rocket, or a high altitude meteorological rocket, occurs in such rarefied regions of the atmos-phere that during this flight phase it is possible to neglect aerodynamic forces acting on the rocket. If, in addition to this, the flight is in the coasting phase, the equations of motion of a rocket, as a mass point, may be inte-grated for any rocket elevation above the earth, no matter how great. FIG. 8.12. Trajectory of a body projected at an angle to the horizon (parabola). It is known in physics that any body thrown at an angle 0 O with respect to the horizontal with velocity VQ, moves (if the air resistance forces are not considered) along a parabola. Indeed, at time t, after initial motion, the coordinates of a thrown body will be x = v 0 t cos 0o y = Vot sin 0o — èô^ 2 · By eliminating t, we find the equation of the parabola shown in Fig. 8.12: y = x tan 0 O — x 2 0 , 2 · 2v 0 2 cos 2 0o The obtained expression, however, is true only within limited bounda-ries. During its derivation it was assumed that the gravity acceleration vector g remains parallel to the axis y for all points on the trajectory, and does not change in value. Actually, this is not so. Acceleration due to gravity 260 ROCKET FLIGHT TRAJECTORY g decreases with increase in altitude, proportionally to the square of the distance from the center of the earth. - eBook - PDF

- Bob Schutz, Byron Tapley, George H. Born(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Chapter 1 Orbit Determination Concepts 1.1 INTRODUCTION The treatment presented here will cover the fundamentals of satellite orbit determination and its evolution over the past four decades. By satellite orbit de-termination we mean the process by which we obtain knowledge of the satellite’s motion relative to the center of mass of the Earth in a specified coordinate system. Orbit determination for celestial bodies has been a general concern of astronomers and mathematicians since the beginning of civilization and indeed has attracted some of the best analytical minds to develop the basis for much of the fundamen-tal mathematics in use today. The classical orbit determination problem is characterized by the assumption that the bodies move under the influence of a central (or point mass) force. In this treatise, we focus on the problem of determining the orbits of noncelestial satellites. That is, we focus on the orbits of objects placed into orbit by humans. These objects differ from most natural objects in that, due to their size, mass, and orbit charateristics, the nongravitational forces are of significant importance. Further, most satellites orbit near to the surface and for objects close to a central body, the gravitational forces depart from a central force in a significant way. By the state of a dynamical system, we mean the set of parameters required to predict the future motion of the system. For the satellite orbit determination problem the minimal set of parameters will be the position and velocity vectors at some given epoch. In subsequent discussions, this minimal set will be expanded to include dynamic and measurement model parameters, which may be needed to improve the prediction accuracy. This general state vector at a time, t , will be denoted as X ( t ) . The general orbit determination problem can then be posed as follows. 1 - Ranjan Vepa(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

The approach direction is from a direction v ∞ and the departure direction in the direction þv ∞ . The angle through which the vehicle turns is called the turning angle. This turning angle can be determined from the properties of the hyperbola. Consequent to this behavior, the flight path angle is not periodic but starts at π=2 and finishes at π=2. Elliptic, parabolic, and hyperbolic orbits are compared in Figure 2.3. In Figure 2.4 a typical hyperbolic orbit is shown and compared with an elliptic orbit. Also shown are the focus where the central body is located and the empty or vacant focus, as well as the origin of the reference axes. Figure 2.4 Hyperbolic orbit. Focus e Perifocus Ellipse Hyperbola Parabola p p p Figure 2.3 Elliptic, parabolic, and hyperbolic orbits. 33 2.2 Planetary Motion: The Two-Body Problem 2.2.3 Orbital Elements Seven numbers, known as satellite orbital elements, are required to define a satellite orbit about a planet. This set of seven numbers is called the satellite’s “Keplerian” orbital elements, or just elements. These numbers define an ellipse, orient it about the planet, and place the satellite on the ellipse at a particular time. In the Keplerian model, satellites orbit in an ellipse of constant shape and orientation. Uniquely associated with an ellipse are two foci and when the two foci coincide, the orbit is circular with a constant radius. The planet is at one focus of the ellipse, not the center (unless the orbit ellipse is actually a perfect circle). The point on the orbit closest to this focus is the perigee, while the farthest point is the apogee. The minimum separation between the satellite and the planet is said to be at periapse and the maximum at apoapse. The direction a satellite or other body travels in orbit can be direct, or prograde, in which the satellite moves in the same direction as the planet rotates, or retrograde, moving in a direction opposite to the planet’s rotation.- Bruce A. Campbell, Paula Walter McCandless(Authors)

- 1996(Publication Date)

- Gulf Professional Publishing(Publisher)

Newton and Kepler formulated their “laws” based on the motions of the planets around the sun, but these relationships describe orbital motions between any two bodies in the universe! In the following sections we will look at these relationships and how they describe the motions and other characteristics of bodies in orbits around the earth. ORBITAL PRINCIPLES Kepler’s Laws Kepler’s First ,aw. Kepler’s first law reveals that :aptive” satellites (those with closed orbital paths) will travel around the earth in elliptical (or circular) paths with the center of the earth located at one of the foci, as depicted in Figure 2- 1. Orbital Parameters. Figure 2-1 defines some of the terms with which we will be dealing, and the geometry of the ellipse reveals some useful relation- ships between these orbital parameters. From the figure it is obvious that: a = semi-major axis Note: a circle is simply an ellipse with a = b r = radial distance between bodies’ mass centers b = semi-minor axis ra = apoapsis radius (maximumdistance between bodies) rp = periapsis radius (minimum distance between bodies) v = true anomaly (measured in same direction as movement in the orbit) Figure 2-1. The ellipse. Many orbital terms can be defined simply by the geometry of an ellipse. Orbital Principles 29 ra + rp ra+rp=2a or a=- 2 where ra and rp represent the upoapsis (maximum) and periapsis (mini- mum) distances between the bodies, respectively. These distances will be better defined shortly. The quantity a is defined as the semi-major axis of the ellipse.- eBook - PDF

Satellite Geodesy

Foundations, Methods, and Applications

- Günter Seeber(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

(1989), Schneider (1981, 1993), Taff (1985), Vinti (1998). Easily readable introductions with special regard to satellite and rocket orbits are Escobal (1965), Bate et al. (1971), Roy (1978), Chobotov (1991), Logsdon (1998), and Montenbruck, Gill (2000). Suitable references with particular emphasis on GPS orbits are Rothacher (1992),Yunck (1996), and Beutler et al. (1998). 3.1.1 Keplerian Motion Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) formulated the three laws of planetary motion associated with his name from an empirical study of observational data collected by Tycho Brahe (1546–1601), an astronomer who mainly worked in Denmark. The three laws give a description of the planetary motion but not an explanation. They provide a very good approximation to the real motion within the solar system because the planetary masses can be neglected when compared to the mass of the sun, and because of the fact that the sun can be considered a point mass due to the large distances involved. This is why the undisturbed gravitational motion of point masses is also called Keplerian motion . From a historical point of view it may be of interest that Kepler, through his three laws, provided the major breakthrough for Copernicus’s heliocentric hypothesis. In the following, Kepler’s laws of planetary motion are introduced and explained. 64 3 Satellite Orbital Motion 1st Law: The orbit of each planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one focus The orbital geometry is defined by this law. The usual relations and symbols are shown in Fig. 3.1. The major axis in the ellipse, A π , is called the line of apsides . The A a M ϕ b ae a y p 0 m ν π = P e x r Figure 3.1. Geometry of the orbital ellipse orbital point A , farthest from the center of mass of the orbital system, 0, is named the apocenter . The point π on the orbit, closest to the center, is named pericen-ter . When 0 is the center of the sun, A and π are called aphelion and perihelion respectively. - Available until 25 Jan |Learn more

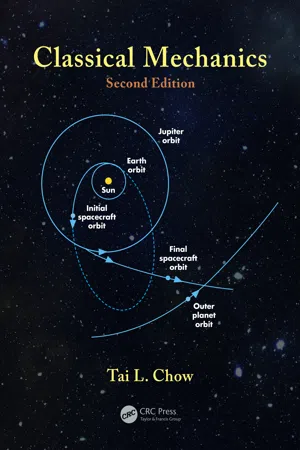

- Tai L. Chow(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

180 Classical Mechanics © 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC orbit as illustrated in Figure 6.16. The orbit of the spacecraft is an elliptical one about the sun with perihelion at the Earth’s orbit, and the planet and the spacecraft meet at the aphelion. The equation of the orbit is given by Equation 6.39: r = + α ε θ 1 cos where α and ε are determined from the maximum and minimum values of r . For planet Uranus, r min = 1 AU (at Earth), r max = 19.2 AU (at Uranus) where AU is the astronomical unit that is the mean Earth–sun distance (~93 × 10 7 mi. or 1.5 × 10 8 km). Thus, r AU r AU min max , . = + = = -= α ε α ε 1 1 1 19 2 . Solving for α and ε , we find ε = 0.9 and α = 1.9. The orbit of the spacecraft to Uranus is r = + 1 9 1 0 9 . . cos θ with the semi-major axis given by a = ( r min + r max )/2 = 10.1 AU . The velocity of the spacecraft at any point on its orbit can be found by using Equation 6.49 or Equation 6.51. The time T at which the spacecraft reaches Uranus at the aphelion is just half of the period given by Kepler’s third law (Equation 6.43): Jupiter orbit Earth orbit Sun Initial spacecraft orbit Final spacecraft orbit Outer planet orbit FIGURE 6.16 Orbits illustrating the gravity-assistance effect. 181 Motion Under a Central Force © 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC T GM a s = = = ≈ τ π 2 1 2 2 1 2 10 1 1 6 3 2 3 2 / / year s y ear s ( . ) . This is quite a long flight time. Fortunately, it can be considerably shortened by means of gravi-tational assists as the spacecraft swings by Jupiter, known as the “slingshot effect” or “gravitational whiplash.” Jupiter and its gravity field are moving around the sun at a speed of approximately 1300 m/s, and any probe passing behind the planet will be accelerated by this moving gravity field much as a surfer is pushed forward by a wave.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.