Physics

Scalar

In physics, a scalar is a physical quantity that is fully described by its magnitude or size, without any direction. Scalars are characterized by their magnitude alone and do not have a specific direction associated with them. Examples of scalars include temperature, mass, and speed.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Scalar"

- eBook - PDF

- William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff Sanny(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

Vector operations also have numerous generalizations in other branches of physics. Chapter 2 | Vectors 43 2.1 | Scalars and Vectors Learning Objectives By the end of this section, you will be able to: • Describe the difference between vector and Scalar quantities. • Identify the magnitude and direction of a vector. • Explain the effect of multiplying a vector quantity by a Scalar. • Describe how one-dimensional vector quantities are added or subtracted. • Explain the geometric construction for the addition or subtraction of vectors in a plane. • Distinguish between a vector equation and a Scalar equation. Many familiar physical quantities can be specified completely by giving a single number and the appropriate unit. For example, “a class period lasts 50 min” or “the gas tank in my car holds 65 L” or “the distance between two posts is 100 m.” A physical quantity that can be specified completely in this manner is called a Scalar quantity. Scalar is a synonym of “number.” Time, mass, distance, length, volume, temperature, and energy are examples of Scalar quantities. Scalar quantities that have the same physical units can be added or subtracted according to the usual rules of algebra for numbers. For example, a class ending 10 min earlier than 50 min lasts 50 min − 10 min = 40 min . Similarly, a 60-cal serving of corn followed by a 200-cal serving of donuts gives 60 cal + 200 cal = 260 cal of energy. When we multiply a Scalar quantity by a number, we obtain the same Scalar quantity but with a larger (or smaller) value. For example, if yesterday’s breakfast had 200 cal of energy and today’s breakfast has four times as much energy as it had yesterday, then today’s breakfast has 4(200 cal) = 800 cal of energy. Two Scalar quantities can also be multiplied or divided by each other to form a derived Scalar quantity. - eBook - PDF

Mathematical Methods for Physicists

A Concise Introduction

- Tai L. Chow(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 Vector and tensor analysis Vectors and Scalars Vector methods have become standard tools for the physicists. In this chapter we discuss the properties of the vectors and vector fields that occur in classical physics. We will do so in a way, and in a notation, that leads to the formation of abstract linear vector spaces in Chapter 5. A physical quantity that is completely specified, in appropriate units, by a single number (called its magnitude) such as volume, mass, and temperature is called a Scalar. Scalar quantities are treated as ordinary real numbers. They obey all the regular rules of algebraic addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and so on. There are also physical quantities which require a magnitude and a direction for their complete specification. These are called vectors if their combination with each other is commutative (that is the order of addition may be changed without aecting the result). Thus not all quantities possessing magnitude and direction are vectors. Angular displacement, for example, may be characterised by magni-tude and direction but is not a vector, for the addition of two or more angular displacements is not, in general, commutative (Fig. 1.1). In print, we shall denote vectors by boldface letters (such as A ) and use ordin-ary italic letters (such as A ) for their magnitudes; in writing, vectors are usually represented by a letter with an arrow above it such as ~ A . A given vector A (or ~ A ) can be written as A A ^ A ; 1 : 1 where A is the magnitude of vector A and so it has unit and dimension, and ^ A is a dimensionless unit vector with a unity magnitude having the direction of A . Thus ^ A A = A . 1 A vector quantity may be represented graphically by an arrow-tipped line seg-ment. The length of the arrow represents the magnitude of the vector, and the direction of the arrow is that of the vector, as shown in Fig. - eBook - PDF

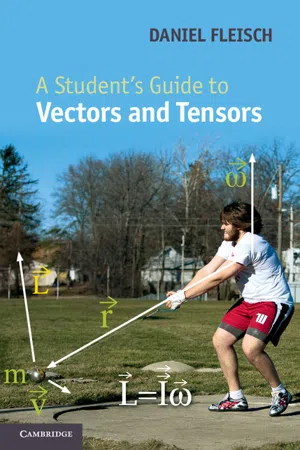

- Daniel A. Fleisch(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

To understand how vectors are different from other entities, it may help to consider the nature of some things that are clearly not vectors. Think about the temperature in the room in which you’re sitting – at each point in the room, the temperature has a value, which you can represent by a single number. That value may well be different from the value at other locations, but at any given point the temperature can be represented by a single number, the magnitude. Such magnitude-only quantities have been called “Scalars” ever since W.R. Hamilton referred to them as “all values contained on the one scale of progres-sion of numbers from negative to positive infinity.” 4 Thus A Scalar is the mathematical representation of a physical entity that may be characterized by magnitude only. Other examples of Scalar quantities include mass, charge, energy, and speed (defined as the magnitude of the velocity vector). It is worth noting that the change in temperature over a region of space does have both magnitude and direction and may therefore be represented by a vector, so it’s possible to pro-duce vectors from groups of Scalars. You can read about just such a vector (called the “gradient” of a Scalar field) in Chapter 2 . Since Scalars can be represented by magnitude only (single numbers) and vectors by magnitude and direction (three numbers in three-dimensional space), you might suspect that there are other entities involving magnitude and directions that are more complex than vectors (that is, requiring more numbers than the number of spatial dimensions). Indeed there are, and such entities are called “tensors.” 5 You can read about tensors in the last three chapters of this book, but for now this simple definition will suffice: 4 W.R. - eBook - PDF

Introduction to Physics

Mechanics, Hydrodynamics Thermodynamics

- P. Frauenfelder, P. Huber(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

For our purposes, it suffices to mention two kinds, Scalars and vectors. DEFINITION. Scalars are quantities that are completely defined by means of a magnitude and a unit. Examples of Scalars are mass (gm), time (sec), volume (cm 3 ), and tem-perature (°C). DEFINITION. Vectors are quantities that are uniquely determined by means of a magnitude, a unit, and a direction in space. Examples of vectors are position vector (r), velocity (»), force (F), and torque ( M ) . The straight line along which a vector acts is called the line of action, or orientation, of the vector. 8 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O P H Y S I C S To clearly distinguish Scalars from vectors, Scalars will be printed in italics, and vectors in boldface. When only the magnitude of a vector is considered, the symbol will be placed between vertical bars or written in italics. For example the symbol F represents a force with a given magnitude and direction; F or |F| represents the magnitude of the force. Scalars, which are determined by a magnitude and a unit, obey the laws of elementary algebra. The situation is more complicated in the case of vec-tors, since the direction of a vector must be considered, as well as its mag-nitude and units. Thus, a vector equation A = Β contains three statements. (1) The magnitude of A must be equal to the magnitude of Β: A = B. (2) The units of A must be equal to the units of B. (3) The direction of A must be the same as the direction of B. 6. VECTOR ALGEBRA 6-1 Graphical Representation and Measurement of Vectors The simplest vector is the displacement vector s, which connects a point A in space to a point Β in space. It has a magnitude of s meters and is directed from A as origin to Β as endpoint. It is represented by an arrow whose length is proportional to the magnitude of the vector. The direction of the vector is fixed by the orientation and the sense of the line representing it. The sense is indicated by the arrow at the end of the line. - P C Kendall, D.E. Bourne(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2 Scalar and vector algebra2.1 Scalars

Any mathematical entity or any property of a physical system which can be represented by a single real number is called a Scalar . In the case of a physical property, the single real number will be a measure of the property in some chosen units (e.g. kilogrammes, metres, seconds).Particular examples of Scalars are: (i) the modulus of a complex number; (ii) mass; (iii) volume; (iv) temperature. Note that real numbers are themselves Scalars.Single letters printed in italics (such as a, b, c , etc.) will be used to denote real numbers representing Scalars. For convenience statements like ‘let a be a real number representing a Scalar’ will be abbreviated to ‘let a be a Scalar’.Equality of Scalars Two Scalars (measured in the same units if they are physical properties) are said to be equal if the real numbers representing them are equal.It will be assumed throughout this book that in the case of physical entities the same units are used on both sides of any equality sign .Scalar addition, subtraction, multiplication and divisionThe sum of two Scalars is defined as the sum of the real numbers representing them. Similarly, Scalar subtraction, multiplication and division are defined by the corresponding operations on the representative numbers. In the case of physical Scalars, the operations of addition and subtraction are physically meaningful only for similar Scalars such as two lengths or two masses.Some care is necessary in the matter of units. For example, if a, b are two physical Scalars it is meaningful to say their sum is a + b only if the units of measurement are the same.Again, consider the equationT =giving the kinetic energy T of a particle of mass m travelling with speed v . If T has the value 30 kg m2 s-2 and v has the value 0.1 km s-1 , then to calculate m -2T /v 2 consistent units for length and time must first be introduced. Thus, converting the given speed to m s-1 we find v has the value 100 m s-l . Hence the value of m1 2mv 2- eBook - ePub

Vector Analysis and Cartesian Tensors

Third Edition

- Donald Edward Bourne(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Chapman and Hall/CRC(Publisher)

Scalar and vector algebra 2 2.1 ScalarSAny mathematical entity or any property of a physical system which can be represented by a single real number is called a Scalar. In the case of a physical property, the single real number will be a measure of the property in some chosen units (e.g. kilogrammes, metres, seconds).Particular examples of Scalars are: (i) the modulus of a complex number; (ii) mass; (iii) volume; (iv) temperature. Note that real numbers are themselves Scalars.Single letters printed in italics (such as a, b, c, etc.) will be used to denote real numbers representing Scalars. For convenience statements like ‘let a be a real number representing a Scalar’ will be abbreviated to ‘let a be a Scalar’.Equality of Scalars Two Scalars (measured in the same units if they are physical properties) are said to be equal if the real numbers representing them are equal.It will be assumed throughout this book that in the case of physical entities the same units are used on both sides of any equality sign.Scalar addition, subtraction, multiplication and divisionThe sum of two Scalars is defined as the sum of the real numbers representing them. Similarly, Scalar subtraction, multiplication and division are defined by the corresponding operations on the representative numbers. In the case of physical Scalars, the operations of addition and subtraction are physically meaningful only for similar Scalars such as two lengths or two masses.Some care is necessary in the matter of units. For example, if a, b are two physical Scalars it is meaningful to say their sum is a + b only if the units of measurement are the same.Again, consider the equationT =giving the kinetic energy T of a particle of mass m travelling with speed v. If T has the value 30 kg m2 s−2 and v has the value 0.1 km s−1 , then to calculate m = 2T/v2 consistent units for length and time must first be introduced. Thus, converting the given speed to m s−1 we find v has the value 100 m s−1 . Hence the value of m1 2mv 2 - eBook - PDF

Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning

Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference (KR '94)

- Jon Doyle, Erik Sandewall, Pietro Torasso, Jon Doyle, Erik Sandewall, Pietro Torasso(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Morgan Kaufmann(Publisher)

Scalar quantities are constant quantities with real-valued magnitudes, distinguished from higher-order tensors. (We will define the magnitude function precisely below.) A physical dimension defines a class of Scalars with important algebraic properties. For example, the sum of any two Scalars of the same dimension is a Scalar of the same dimension. Physical dimensions also provide necessary conditions for comparing quantities; two quantities are comparable only if they are of the same physical dimension. It makes sense to quantitatively compare two masses but not a mass and a length. 33 COMPARABILITY AND ORDER Comparability is one way to ground the otherwise algebraic definitions of quantities. Quantities are quantitative measures; a meaningful measure is one that reflects order in the measured (or we would say, modeled) world. Adapting the definition by Ellis [11], we say that the elements of a class Q of (Scalar) quantities of the same physical dimension must be comparable . According to Ellis, comparability for a quantity type holds if there is as a linear ordering relationship in the world given by an equivalence relation R = , and a binary relation R< that is asymmetric and transitive over Q, such that for any two quantities q, q2 e Q, exactly one of the following must hold: qi R= q2, qi R< q2> or q2 R< qi. Using this definition, we can ask whether something we want to call a quantity type or physical dimension should be classified as such. Mass, for instance, is comparable by this definition because one can always order masses. The property of comparability is independent of measurement unit, measurement procedure, scales, or the types of physical objects that are being modeled. Ellis defines a quantity [type] as exactly that which can be linearly ordered. We needed to depart on two fronts, to accommodate the sorts of quantities we find in engineering models. - eBook - PDF

- Bhag Singh Guru, Hüseyin R. Hiziroglu(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

2 Vector analysis 2.1 Introduction ................................. Knowledge of vector algebra and vector calculus is essential in de-veloping the concepts of electromagnetic field theory. The widespread acceptance of vectors in electromagnetic field theory is due in part to the fact that they provide compact mathematical representations of complicated phenomena and allow for easy visualization and manipula-tion. The ever-increasing number of textbooks on the subject are further evidence of the popularity of vectors. As you will see in subsequent chapters, a single equation in vector form is sufficient to represent up to three Scalar equations. Although a complete discussion of vectors is not within the scope of this text, some of the vector operations that will play a prominent role in our discussion of electromagnetic field theory are introduced in this chapter. We begin our discussion by defining Scalar and vector quantities. 2.2 Scalar and vector quantities ................................. Most of the quantities encountered in electromagnetic fields can easily be divided into two classes, Scalars and vectors. 2.2.1 Scalar A physical quantity that can be completely described by its magnitude is called a Scalar . Some examples of Scalar quantities are mass, time, temperature, work, and electric charge. Each of these quantities is com-pletely describable by a single number. A temperature of 20 ◦ C, a mass of 100 grams, and a charge of 0.5 coulomb are examples of Scalars. In fact, all real numbers are Scalars. 2.2.2 Vector A physical quantity having a magnitude as well as a direction is called a vector . Force, velocity, torque, electric field, and acceleration are vector quantities. 14 15 2.3 Vector operations A vector quantity is graphically depicted by a line segment equal to its magnitude according to a convenient scale, and the direction is indicated by means of an arrow, as shown in Figure 2.1a. - eBook - PDF

- Nelson Bolívar(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Arcler Press(Publisher)

The small curve segment can be approximated around the point P with an arc of the osculating circle and consider the point as moving on arc with the angular velocity ω = υ / R . In conclusion, two components of acceleration are as: 2 t n dv v a ,a . dt R = = (52) 3.13. VECTORS, PSEUDOVECTORS, ScalarS, AND PSEUDOScalarS Previously, the vector is defined as a well-ordered triple of the real numbers that under the rotations of reference frame changes in same way as the triplet characterizing the position vector (Kamiński et al., 1997; Maris and Roberts, 1998). Previously, a Scalar quantity is introduced, dot product of the two vectors. It is seen that Scalar quantity is same in the two reference frames differing for the rotation of axes. Indeed, generally, a quantity, by definition, is Scalar if the quantity is invariant under the change of reference frame (Hsiao et al., 2000; Chou, 2009). Hence, both Scalar and vector properties are articulated in terms of changes between the reference frames. Let’s now contemplate the behaviors of both these quantities under inversion of the axes. It is known as a parity operation. It leads from the left-handed frame to right-handed one (McConnell, 1958; Bennhold and Wright, 1987). Consider the variation properties of the physical quantities. The quantity can be Scalar or can be pseudoScalar. Both are invariant under the rotations General Physics 80 but the earlier is invariant under the parity operation, the latter varies sign, whereas keeping the absolute value (Deo and Bisoi, 1974; Chiu et al., 2006). The dot product of the two vectors is Scalar; the Scalar triple product is pseudoScalar. This is immediately evident seeing that under the inversion of axes all the 3 vector factors transform sign. The quantity can be vector or pseudovector (Norton and Watson, 1958; Sugawara and Okubo, 1960). - eBook - PDF

- John D. Cutnell, Kenneth W. Johnson, David Young, Shane Stadler(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

One second is the time for a certain type of electromagnetic wave emitted by cesium-133 atoms to undergo 9 192 631 770 wave cycles. 1.3 The Role of Units in Problem Solving To convert a number from one unit to another, multiply the number by the ratio of the two units. For instance, to convert 979 meters to feet, multiply 979 meters by the factor (3.281 foot/1 meter). The dimension of a quantity represents its physical nature and the type of unit used to specify it. Three such dimensions are length [L], mass [M], time [T]. Dimensional analysis is a method for checking mathematical relations for the consistency of their dimensions. 1.4 Trigonometry The sine, cosine, and tangent functions of an angle u are defined in terms of a right triangle that contains u, as in Equations 1.1–1.3, where h o and h a are, respectively, the lengths of the sides opposite and adjacent to the angle u, and h is the length of the hypotenuse. The inverse sine, inverse cosine, and inverse tangent functions are given in Equations 1.4–1.6. The Pythagorean theorem states that the square of the length of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other two sides, according to Equation 1.7. 1.5 Scalars and Vectors A Scalar quantity is described by its size, which is also called its magnitude. A vector quantity has both a magnitude and a direction. Vectors are often represented by arrows, the length of the arrow being proportional to the magnitude of the vector and the direction of the arrow indicating the direction of the vector. 1.6 Vector Addition and Subtraction One procedure for adding vectors utilizes a graphical technique, in which the vectors to be added are arranged in a tail-to-head fashion. The resultant vector is drawn from the tail of the first vector to the head of the last vector. The subtraction of a vector is treated as the addition of a vector that has been multiplied by a Scalar factor of 21.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.