Mathematics

Vectors in Space

Vectors in space are quantities that have both magnitude and direction. In three-dimensional space, vectors are represented by arrows with a specific length and direction. They are used to describe physical quantities such as force, velocity, and displacement. Vectors can be added, subtracted, and multiplied by scalars, making them essential in various mathematical and scientific applications.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Vectors in Space"

- No longer available |Learn more

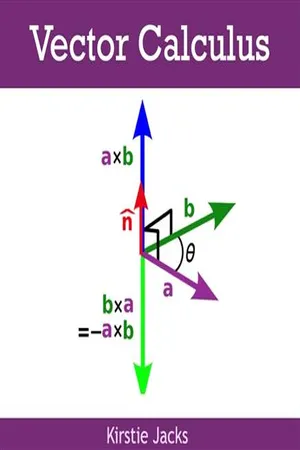

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- White Word Publications(Publisher)

The mathematical representation of a physical vector depends on the coordinate system used to describe it. Other vector-like objects that describe physical quantities and transform in a similar way under changes of the coordinate system include pseudovectors and tensors. Overview A vector is a geometric entity characterized by a magnitude (in mathematics a number, in physics a number times a unit) and a direction. In rigorous mathematical treatments, a vector is defined as a directed line segment, or arrow, in a Euclidean space. When it becomes necessary to distinguish it from vectors as defined elsewhere, this is sometimes referred to as a geometric , spatial , or Euclidean vector. As an arrow in Euclidean space, a vector possesses a definite initial point and terminal point . Such a vector is called a bound vector . When only the magnitude and direction of the vector matter, then the particular initial point is of no importance, and the vector is called a free vector . Thus two arrows and in space represent the same free vector if they have the same magnitude and direction: that is, they are equivalent if the quadrilateral ABB′A′ is a parallelogram. If the Euclidean space is equipped with a choice of origin, then a free vector is equivalent to the bound vector of the same magnitude and direction whose initial point is the origin. The term vector also has generalizations to higher dimensions and to more formal approaches with much wider applications. Examples in one dimension Since the physicist's concept of force has a direction and a magnitude, it may be seen as a vector. As an example, consider a rightward force F of 15 newtons. If the positive axis is also directed rightward, then F is represented by the vector 15 N, and if positive points leftward, then the vector for F is −15 N. In either case, the magnitude of the vector is 15 N. - eBook - PDF

Learning and Teaching Mathematics using Simulations

Plus 2000 Examples from Physics

- Dieter Röss(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

In quantum mechanics one works with vectors in the infinitely dimensional Hilbert space. Plane problems can be described by two-dimensional vectors that can be considered to lie in the complex plane. Vector algebra and vector analysis, in which partial differentiations take place, are an especially important mathematical tool of theoretical physics and therefore are often treated in depth in many textbooks for first year students.Their objects and oper-ations are not easily accessible to the untrained imagination. Therefore, the following sections concentrate only on the interactive visualization of fundamental aspects. 8.2 3D-visualization of vectors The classical visual presentation of a vector is an arrow in space, whose length defines an absolute value and whose orientation defines a direction. The place at which the arrow is situated is arbitrary; one can, for example, let it start as a zero-point vector from the origin of a Cartesian system of coordinates. Thus its endpoint (the tip of the arrow) is described by the three space coordinates x; y; z in this system of coordinates. Its length a , also referred to as the absolute value of the vector, is obtained from the theorem of Pythagoras as a D p x 2 C y 2 C z 2 . It obviously does not matter how the system of coordinates, with respect to which the coordinates of the vector are defined, is orientated in space. Under a change of the coordinate system (translation or rotation), the individual coordinates also change, but the position and length of the vector are not affected by this. They are invariant under translation and rotation. This property provides the definition of a vector. Quantities that can be characterized by specifying a single number for every point in space are called scalar , in contract to vectors; an example would be a density-or temperature distribution. The three-dimensional zero-point vector represents the position coordinates of a point in space. - eBook - PDF

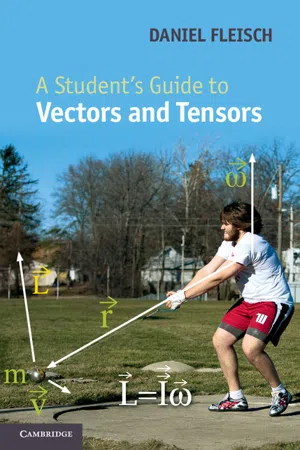

- Daniel A. Fleisch(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 Vectors 1.1 Definitions (basic) There are many ways to define a vector. For starters, here’s the most basic: A vector is the mathematical representation of a physical entity that may be characterized by size (or “magnitude”) and direction. In keeping with this definition, speed (how fast an object is going) is not rep-resented by a vector, but velocity (how fast and in which direction an object is going) does qualify as a vector quantity. Another example of a vector quantity is force, which describes how strongly and in what direction something is being pushed or pulled. But temperature, which has magnitude but no direction, is not a vector quantity. The word “vector” comes from the Latin vehere meaning “to carry;” it was first used by eighteenth-century astronomers investigating the mechanism by which a planet is “carried” around the Sun. 1 In text, the vector nature of an object is often indicated by placing a small arrow over the variable representing the object (such as F ), or by using a bold font (such as F ), or by underlining (such as F or F ∼ ). When you begin hand-writing equations involving vectors, it’s very important that you get into the habit of denoting vectors using one of these techniques (or another one of your choosing). The important thing is not how you denote vectors, it’s that you don’t simply write them the same way you write non-vector quantities. A vector is most commonly depicted graphically as a directed line seg-ment or an arrow, as shown in Figure 1.1 (a). And as you’ll see later in this section, a vector may also be represented by an ordered set of N numbers, 1 The Oxford English Dictionary . 2nd ed. 1989. 1 2 Vectors (b) (a) Figure 1.1 Graphical depiction of a vector (a) and a vector field (b). where N is the number of dimensions in the space in which the vector resides. Of course, the true value of a vector comes from knowing what it represents. - Robert E. White(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Chapman and Hall/CRC(Publisher)

Chapter 2 Vectors in Space Vectors in Space are introduced, and the dot, cross and box products are stud-ied. Lines and planes are carefully described as well as extensions to higher dimensional space. Applications to work, torque, inventories and visualizations are included. 2.1 Vectors and Dot Product A point in space can be located in a number of ways, but here the Cartesian coordinate system will be used. You may wish to visualize this from the interior of a room looking down into the corner. The corner is the origin; the x-axis is the intersection of the left wall and floor; the y-axis is the intersection of the right wall and the floor; the intersection of the left and right walls is the z-axis. This is illustrated in Figure 2.1.1. The point ( ) is located by moving units in the x-axis, then moving units parallel to the y-axis, and moving units parallel to the z-axis. The distance from the origin to the point is given by two applications of the Pythagorean theorem to the right triangles in Figure 2.1.1. Associated with the point ( ) is the position vector from the origin to this point. Definition 2.1.1. A vector in R 3 is an ordered list of three real numbers = [ 1 2 3 ] . One can visualize this by forming the directed line segment from the origin point (0 0 0) to the point ( 1 2 3 ) Notation. Points in R 3 will be denoted by ( 1 2 3 ) and vectors will be represented by either row or column vectors: = [ 1 2 3 ] indicates a row vector a = 1 2 3 indicates a column vector a = [ 1 2 3 ] is called the transpose of the column vector a so that a = 47 48 CHAPTER 2. Vectors in Space Figure 2.1.1: Point in Space Example 2.1.1.- Joseph C. Amato, Enrique J. Galvez(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

33 2 VECTORS Mathematics allows the most sweeping properties of the universe to be calculated and expressed concisely. This blackboard was used by Albert Einstein during a lecture given at Oxford University in 1931. The last three lines contain estimates of the density (ρ = 10 –26 kg/m 3 ), size ( P = 10 8 ly), and age ( t = 10 10 –10 11 years) of the universe. The blackboard is on permanent display at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford, England. (From the public domain.) Physics and mathematics are inextricably entwined. How lucky we are, and how amazing it is, that the laws of physics can be expressed so precisely and elegantly in mathematical form. In contrast to conventional wisdom, mathematics simplifies the analysis of physical phenomena, enabling us to study increasingly complicated—hence more realistic—physical situations. Whenever new (higher?) mathematics is introduced, it is done to ease and empower analysis and to promote deeper understanding. Imagine how difficult it would be to describe motion without the use of negative numbers. Plane geometry, used throughout Chapter 1, is restricted to two dimensions. To describe motion in the real three-dimensional world, we need to introduce new, more versatile, mathematical tools. These powerful tools, called vectors , are the subject of this chapter. 34 Physics from Planet Earth - An Introduction to Mechanics 2.1 INTRODUCTION Blame it on René Descartes. As the story goes, the seventeenth century physicist, mathematician, and philos -opher * was lying in bed one morning lazily watching a fly wander about on the ceiling above him. Descartes wondered how he could describe the fly’s position precisely and unambiguously. He soon realized he could do this by defining the fly’s position in terms of its perpendicular distance from each of the two adjacent walls of the room ( Figure 2.1a ). Nowadays, we would call these two distances the fly’s coordinates .- eBook - PDF

- John Gilbert, Camilla Jordan, David A Towers(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 9 Vectors By the end of this chapter you will have • been introduced to the terminology and notation of vec-tors; • used scalar and vector products; • seen triple scalar and triple vector products and their geometric interpretation; • learnt about vector functions and how to differentiate them. Aims and Objectives 9.1 Vectors Up to now we have used real numbers to represent the magnitude of physical quantities, such as mass and length, which are unrelated to any direction in space. We shall call such quantities scalars : they obey the ordinary rules of algebra. However, there are many physical quantities, such as velocity and force, which are only specified completely when a direction is given as well as a magnitude. We call such quantities vectors and we shall develop an algebra for their manipulation. In many applications we shall find that this leads to very elegant and concise solutions. When we have to apply the result to a practical situation, we usually find it necessary to describe the vectors in terms of their coordinates. For this reason, as well as to ease the derivation of algebraic rules for vectors, we start with a brief study of coordinate systems. Coordinate systems In order to measure the lengths and directions of lines, we need some kind of reference system. 205 206 Guide to Mathematical Methods x y O P ( x , y ) x y Figure 9.1: Two-dimensional coordinates In two-dimensional space, we set up mutually perpendicular axes, intersecting at an origin, O . We refer to these axes as rectangular Cartesian axes (after Descartes 1596–1650) and designate the positive directions of the axes as Ox (the x -axis) and Oy (the y -axis). The x and y coordinates of a point P are defined by the perpendicular distances, x and y , of P from Oy and Ox re-spectively, as shown in Figure 9.1. We say that P has coordinates ( x , y ). We note that the length of OP can be obtained, using Pythagoras’ Theorem, as x 2 + y 2 . - eBook - PDF

- James Stewart, Daniel K. Clegg, Saleem Watson, , James Stewart, James Stewart, Daniel K. Clegg, Saleem Watson(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 880 CHAPTER 12 Vectors and the Geometry of Space A unit vector is a vector whose length is 1. For instance, i, j, and k are all unit vectors. In general, if a ± 0, then the unit vector that has the same direction as a is 4 u - 1 | a | a - a | a | In order to verify this, we let c - 1 y | a | . Then u - c a and c is a positive scalar, so u has the same direction as a. Also | u | - | c a | - | c || a | - 1 | a | | a | - 1 EXAMPLE 6 Find the unit vector in the direction of the vector 2 i 2 j 2 2 k. SOLUTION The given vector has length | 2 i 2 j 2 2 k | - s2 2 1 s21d 2 1 s22d 2 - s9 - 3 so, by Equation 4, the unit vector with the same direction is 1 3 s2 i 2 j 2 2 kd - 2 3 i 2 1 3 j 2 2 3 k ■ ■ Applications Vectors are useful in many aspects of physics and engineering. In Chapter 13 we will see how they describe the velocity and acceleration of objects moving in space. Here we first look at forces. A force is represented by a vector because it has both magnitude (measured in pounds or newtons) and direction. If several forces are acting on an object, the resultant force experienced by the object is the vector sum of these forces. EXAMPLE 7 A 100 kg weight hangs from two wires as shown in Figure 19. Find the tensions (forces) T 1 and T 2 in the wires and the magnitudes of these tensions. 100 T¡ 50° 32° T™ SOLUTION We first express T 1 and T 2 in terms of their horizontal and vertical compo- nents. From Figure 20 we see that 5 T 1 - 2 | T 1 | cos 50° i 1 | T 1 | sin 50° j 6 T 2 - | T 2 | cos 32° i 1 | T 2 | sin 32° j The force of gravity acting on the load is F - 2100s9.8d j - 2980 j. - eBook - PDF

- James Stewart, Daniel K. Clegg, Saleem Watson, , James Stewart, James Stewart, Daniel K. Clegg, Saleem Watson(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 842 CHAPTER 12 Vectors and the Geometry of Space A unit vector is a vector whose length is 1. For instance, i, j, and k are all unit vectors. In general, if a ± 0, then the unit vector that has the same direction as a is 4 u - 1 | a | a - a | a | In order to verify this, we let c - 1 y | a | . Then u - c a and c is a positive scalar, so u has the same direction as a. Also | u | - | c a | - | c || a | - 1 | a | | a | - 1 EXAMPLE 6 Find the unit vector in the direction of the vector 2 i 2 j 2 2 k. SOLUTION The given vector has length | 2 i 2 j 2 2 k | - s2 2 1 s21d 2 1 s22d 2 - s9 - 3 so, by Equation 4, the unit vector with the same direction is 1 3 s2 i 2 j 2 2 kd - 2 3 i 2 1 3 j 2 2 3 k ■ ■ Applications Vectors are useful in many aspects of physics and engineering. In Chapter 13 we will see how they describe the velocity and acceleration of objects moving in space. Here we first look at forces. A force is represented by a vector because it has both magnitude (measured in pounds or newtons) and direction. If several forces are acting on an object, the resultant force experienced by the object is the vector sum of these forces. EXAMPLE 7 A 100 kg weight hangs from two wires as shown in Figure 19. Find the tensions (forces) T 1 and T 2 in the wires and the magnitudes of these tensions. 100 T¡ 50° 32° T™ SOLUTION We first express T 1 and T 2 in terms of their horizontal and vertical compo- nents. From Figure 20 we see that 5 T 1 - 2 | T 1 | cos 50° i 1 | T 1 | sin 50° j 6 T 2 - | T 2 | cos 32° i 1 | T 2 | sin 32° j The force of gravity acting on the load is F - 2100s9.8d j - 2980 j. - eBook - PDF

- Harold Jeffreys, Bertha Jeffreys(Authors)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

What we shall do in the present chapter is to show the two methods, as far as possible, side be- side. Ability to translate from either language to the other, or to the expanded form, is an absolute necessity in understanding modern physical literature. It is often useful to visualize a vector as a displacement vector, and while as a matter of definition we make a clear distinction between a general vector and a displacement vector, we shall frequently speak of a general vector in geometrical terms: e.g. the angle between two vectors A and B means strictly 'the angle between the displacement vectors representing A and B according to some specified scale'; * two perpendicular vectors A and B* means 'two vectors A and B such that the displacements representing them are perpendicular'. The use of this analogy is unnecessary in suffix notation, analytical definitions being provided. 2*033. Null vector. A null or zero vector is one whose modulus is zero. 2*034. Direction vectors. A vector of modulus 1 (a number) in the direction of a vector A is called a unit or direction vector in that direction. Its components are evidently l i9 the direction cosines of the direction of A with regard to the coordinate axes. In particular we shall denote direction vectors in the directions of the axes by e (1) , e (2 ), e^ respectively; that is, e (1) = (1,0,0), e (2) = (0,1,0), e (3) = (0,0,1). The use of the brackets round the suffix is to emphasize that it does not denote a com- ponent, but a particular vector. Any vector A may be written as ^ I e ( l ) + ^2 e (2) + ^3*3(3)- Some books denote direction vectors parallel to the axes by i f j, k and write A = A x i + A y j + A 8 k. 2-04. Linearly dependent or coplanar vectors. If there is a relation aA + fiB + yC = 0 (1) between three vectors, where a.fi^y are real numbers (not all zero), then A, B, C are said to be linearly dependent. - eBook - PDF

Linear Algebra

A First Course with Applications

- Larry E. Knop(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Chapman and Hall/CRC(Publisher)

C H A P T E R 1 An Introduction to Vector Spaces SECTION 1.1: THE VECTOR SPACE R 2 — THE BASICS A little learning is a dangerous thing; drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain, and drinking largely sobers us again. Alexander Pope Although we claim to be 3-dimensional beings, much of our mathematical lives has been lived in the plane. The set of ordered pairs of real numbers, {( x, y ) j x, y are real}, is our favored mathematical hangout (thus far anyway) for many good reasons. A visual repre-sentation of the plane is given by the Cartesian (or rectangular) coordinate system, and allows us to picture what we do. The Cartesian coordinate system is illustrated in Figure 1. x y ( x , y ) FIGURE 1 Actual physical representations of planes are everywhere, from the sheet of paper on which these words are printed, to the board on which your teacher writes, to the fl oor beneath your feet. The plane is also a good place to work because it is relatively small and friendly, yet at the same time it has enough complexity to be interesting. If we de fi ne the (Euclidean) distance between two points ( x 1 , y 1 ) and ( x 2 , y 2 ) to be the number dist x 1 , y 1 ð Þ , x 2 , y 2 ð Þ ð Þ ¼ ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi ( x 2 x 1 ) 2 þ ( y 2 y 1 ) 2 q , 53 then we can take the measure of all manner of things. Within the plane we can also investigate (Euclidean) geometry, graph functions such as y ¼ x 3 , and plot relationships between physical variables. In short, the plane is a delightful (and delightfully comfortable) setting for doing mathematics. There has been something missing from our good times in the plane however, and what ’ s missing is arithmetic. Your immediate reaction may be to say: ‘‘ Yes, and good riddance! ’’ Please restrain that impulse. The doing of arithmetic can be drudgery or worse, but the ability to combine numbers to get other numbers is a tool that can work magic. - eBook - PDF

Linear Algebra: Gateway to Mathematics

Second Edition

- Robert Messer(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- American Mathematical Society(Publisher)

A vector field assigns to each point of the underlying set ℝ 2 a vector in the vector space ? . This can be described by a function 𝑭 ∶ ℝ 2 → ? . If ? is ℝ 2 , we can represent the vector 𝑭(?) associated with any point ? by an arrow from ? to ? + 𝑭(?) . This arrow is a translation of the standard vector with its tail at the origin that usually depicts 𝑭(?) . Sketch some vectors to represent the vector field defined by 𝑭(?, ?) = (−0.1?, −0.1?). Modify this function so that it might describe gravitational attraction in a planar uni-verse. A. K. Dewdney describes such a world in great detail in his book The Planiverse: Computer Contact with a Two-Dimensional World , published in 1984 by Poseidon Press. Sketch the vector field defined by 𝑭(?, ?) = (−0.2?, 0.2?) . Modify this to make the arrows circle clockwise. Can you modify the function so that the vector field has an elliptical look or a slight outward spiral? Can you cook up a vector field that spirals around two or more points? 2. Vector fields are often used to describe the motion a particle undergoes if it is free to drift through the field. In this context a vector field is called a direction field rather than a force field. A direction field gives a global picture of motion. This is invaluable to meteorologists and oceanographers, who need to envision large masses of air or water under the influence of a direction field. The constant direction vector field 𝑭(?, ?) = (2, 0) represents a constant flow in the positive ? -direction. Experiment with modifications of this vector field to create a vector field that might more realistically describe the motion of a river, streamlines in a wind tunnel, ocean currents, or wind in a hurricane. 3. Once you have sketched a few vector fields by hand, you will probably appreci-ate the power of a computer in creating these diagrams. - eBook - PDF

Calculus

Concepts and Contexts, Enhanced Edition

- James Stewart(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 648 CHAPTER 9 VECTORS AND THE GEOMETRY OF SPACE 38. Suppose a vector makes angles , , and with the positive -, -, and -axes, respectively. Find the components of and show that (The numbers , , and are called the direction cosines of .) 39. If and , describe the set of all points such that . 40. If , , and , describe the set of all points such that , where . 41. Figure 16 gives a geometric demonstration of Property 2 of vectors. Use components to give an algebraic proof of this fact for the case . 42. Prove Property 5 of vectors algebraically for the case . Then use similar triangles to give a geometric proof. 43. Use vectors to prove that the line joining the midpoints of two sides of a triangle is parallel to the third side and half its length. n 3 n 2 k r 1 r 2 r r 1 r r 2 k x , y r 2 x 2 , y 2 r 1 x 1 , y 1 r x , y r r 0 1 x , y , z r 0 x 0 , y 0 , z 0 r x , y , z a cos cos cos cos 2 cos 2 cos 2 1 a z y x a 44. Suppose the three coordinate planes are all mirrored and a light ray given by the vector first strikes the -plane, as shown in the figure. Use the fact that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection to show that the direc-tion of the reflected ray is given by . Deduce that, after being reflected by all three mutually perpendicular mirrors, the resulting ray is parallel to the initial ray. (American space scientists used this principle, together with laser beams and an array of corner mirrors on the moon, to calculate very precisely the distance from the earth to the moon.) b a z x y b a 1 , a 2 , a 3 x z a a 1 , a 2 , a 3 So far we have added two vectors and multiplied a vector by a scalar.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.