Physics

Vector Problems

Vector problems in physics involve the manipulation and analysis of quantities that have both magnitude and direction. These problems often require the use of vector addition, subtraction, and decomposition to solve for unknown quantities. Understanding vector problems is crucial for accurately representing and analyzing physical phenomena, such as forces, velocities, and accelerations, in both one and multiple dimensions.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Vector Problems"

- David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

C H A P T E R 3 What Is Physics? Physics deals with a great many quantities that have both size and direction, and it needs a special mathematical language—the language of vectors—to describe those quantities. This language is also used in engineering, the other sciences, and even in common speech. If you have ever given directions such as “Go five blocks down this street and then hang a left,” you have used the language of vectors. In fact, navigation of any sort is based on vectors, but physics and engineering also need vectors in special ways to explain phenomena involving rotation and magnetic forces, which we get to in later chapters. In this chapter, we focus on the basic language of vectors. Vectors and Scalars A particle moving along a straight line can move in only two directions. We can take its motion to be positive in one of these directions and negative in the other. For a particle moving in three dimensions, however, a plus sign or minus sign is no longer enough to indicate a direction. Instead, we must use a vector. After reading this module, you should be able to . . . 3.1.1 Add vectors by drawing them in head-to-tail arrangements, applying the commutative and associative laws. 3.1.2 Subtract a vector from a second one. 3.1.3 Calculate the compo- nents of a vector on a given coordinate system, showing them in a drawing. 3.1.4 Given the components of a vector, draw the vector and determine its magnitude and orientation. 3.1.5 Convert angle measures between degrees and radians. 3.1 VECTORS AND THEIR COMPONENTS LEARNING OBJECTIVES Vectors KEY IDEAS 1. Scalars, such as temperature, have magnitude only. They are specified by a num- ber with a unit (10°C) and obey the rules of arithmetic and ordinary algebra. Vectors, such as displacement, have both magnitude and direction (5 m, north) and obey the rules of vector algebra. 2. Two vectors a → and b → may be added geometrically by drawing them to a com- mon scale and placing them head to tail.- eBook - PDF

- Robert Resnick, David Halliday, Kenneth S. Krane(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

In contrast to vectors, quantities that can be completely de- scribed by specifying only a number (and its units) are called scalars. Examples of scalars are mass, time, temper- ature, and energy. Kinematics In this chapter we begin our study of the motion of ob- jects by introducing the terms that are used to describe the motion and showing how they are related to one an- other. This branch of physics is called kinematics. By specifying the position, velocity, and acceleration of an object, we can describe how the object moves, including the direction of its motion, how that direction changes with time, whether the object speeds up or slows down, and so forth. For simplicity we will in this chapter consider only the motion of particles. By “particle” we often mean a single mass point, such as an electron, but we also can use “par- ticle” to describe an object whose parts all move in ex- actly the same way. Even a complex object can be treated as a particle if there are no internal motions such as rota- tions or vibrations of its parts. For example, a rolling wheel cannot be treated as a particle, because a point on its rim moves differently from a point on its axle. (How- ever, a sliding wheel can be treated as a particle.) Thus an object may be considered a particle for some calculations but not for others. For now we will neglect all internal motions and consider an electron and a freight train on the same basis — as examples of particle motion. Within this approximation, particles can execute a variety of mo- tions: speed up, slow down, even stop and reverse direc- tion or move in curved paths such as circles or parabolas. As long as we can regard these objects as particles, we can use the same set of kinematic equations to describe them. Many of the laws of physics can be expressed most compactly as relations between quantities expressed as vectors. When a law is written in vector form, it is often easier to understand and to manipulate. - eBook - PDF

- Stephen Lee(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

17 Use of vectors This grand book – the Universe… is written in the language of mathematics Galileo Galilei (1623) Vectors are important in modelling and solving two- and three-dimensional problems in mechanics. You have already used vector methods. This chapter will help you to review and consolidate your knowledge of vectors with particular reference to their application in mechanics. 17.1 Vector basics A vector is a quantity with both magnitude (also known as length, size or modulus) and direction. In mechanics, vectors are used to represent quantities such as displacement, velocity, acceleration, force and momentum. A vector is usually written PQ ⎯→ or a and is typeset as PQ ⎯→ or as bold PQ or a . In figure 17.1, PQ ⎯→ QA ⎯→ because their lengths and directions are the same. Figure 17.1 Vectors can be added: a b c and subtracted: a b d and multiplied by a scalar: a has magnitude magnitude of a . Figure 17.2 The length of the vector a is denoted a or a . When a 1, a is a unit vector . A unit vector is denoted by having a hat a . The position vector of a point A relative to a point O is the vector OA ⎯→ . Normally, O is the origin of Cartesian axes and the position vector of a point is usually denoted by the corresponding lower-case letter, thus OA ⎯→ a , OB ⎯→ b , and so on. Then AB ⎯→ b a , a d c 2 a a a b b P Q Q A a a 378 AN INTRODUCTION TO MATHEMATICS FOR ENGINEERS : MECHANICS where b and a are the position vectors of A and B with respect to an assumed origin (figure 17.3) which is not necessarily drawn on the diagram. AB ⎯→ OA ⎯→ OB ⎯→ OA ⎯→ OB ⎯→ a b b a Figure 17.3 Cartesian components Vectors can also be expressed in Cartesian component form, with respect to some appropriate origin and axes. In three dimensions: OA ⎯→ x i y i z k where a , y , z are the displacements represented by the vector in the x , y and z directions and i , j and k are the unit vectors in the directions of the co-ordinate axes. - eBook - PDF

- William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff Sanny(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

We can apply the same basic equations for displacement, velocity, and acceleration we derived in Motion Along a Straight Line to describe the motion of the jets in two and three dimensions, but with some modifications—in particular, the inclusion of vectors. In this chapter we also explore two special types of motion in two dimensions: projectile motion and circular motion. Last, we conclude with a discussion of relative motion. In the chapter-opening picture, each jet has a relative motion with respect Chapter 4 | Motion in Two and Three Dimensions 157 to any other jet in the group or to the people observing the air show on the ground. 4.1 | Displacement and Velocity Vectors Learning Objectives By the end of this section, you will be able to: • Calculate position vectors in a multidimensional displacement problem. • Solve for the displacement in two or three dimensions. • Calculate the velocity vector given the position vector as a function of time. • Calculate the average velocity in multiple dimensions. Displacement and velocity in two or three dimensions are straightforward extensions of the one-dimensional definitions. However, now they are vector quantities, so calculations with them have to follow the rules of vector algebra, not scalar algebra. Displacement Vector To describe motion in two and three dimensions, we must first establish a coordinate system and a convention for the axes. We generally use the coordinates x, y, and z to locate a particle at point P(x, y, z) in three dimensions. If the particle is moving, the variables x, y, and z are functions of time (t): (4.1) x = x(t) y = y(t) z = z(t). The position vector from the origin of the coordinate system to point P is r → (t). In unit vector notation, introduced in Coordinate Systems and Components of a Vector, r → (t) is (4.2) r → (t) = x(t) i ^ + y(t) j ^ + z(t) k ^ . Figure 4.2 shows the coordinate system and the vector to point P, where a particle could be located at a particular time t. - eBook - PDF

- Ronald Huston, C Q Liu(Authors)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Chapter 2 VECTOR ANALYSIS AND PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS 2.1 Introduction In this chapter we briefly review and present some operational formulas, primarily from elementary vector analysis, which form the basis for the dynamics formulations of the subsequent chapters. We develop and illustrate many of the formulas through a series of examples. The references at the end of this chapter provide a more comprehensive review. 2.2 Fundamental Concepts • Vectors — Mathematically, a vector is an element of a vector space [2.1, 2.2, 2.3]. Since dynamics is fundamentally a geometric subject it is helpful to think of vectors as being directed line segments. Symbolically, vectors are written in bold face type (for example, v). • Vector Characteristics — The characteristics of a vector are its magnitude (length) and direction (orientation and sense). The units of a vector are the same units of those of its magnitude. The magnitude of a vector, say v, is written as | v | . • Equality of Vectors — Two vectors a and b are said to be equal (a = b) if they have the same characteristics (magnitude and direction). • Scalar — A scalar is simply a variable or parameter. Scalars may be either real or complex numbers, although in dynamics they are generally real numbers. They may be positive or negative. Frequently appearing scalars in dynamics are time, distance, mass, and force, velocity and acceleration magnitudes. 12 Vector Analysis 13 • Multiplication of Scalars and Vectors — Let D be a scalar and let V be a vector. Then the product sV is a vector with the same orientation and sense as V if s is positive, and with the same orientation but opposite sense of V if s is negative. The magnitude of sV is |s| |V|. (See Section 2.5.) • Negative Vector — The negative of vector V, written as -V, is a vector with the same magnitude and orientation as V, but with opposite sense to that of V. - eBook - PDF

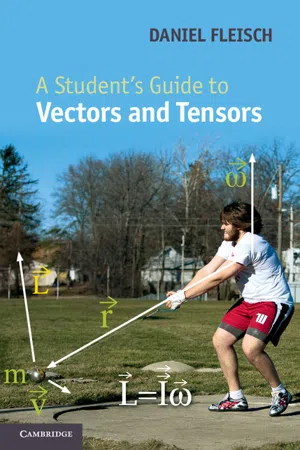

- Daniel A. Fleisch(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 Vectors 1.1 Definitions (basic) There are many ways to define a vector. For starters, here’s the most basic: A vector is the mathematical representation of a physical entity that may be characterized by size (or “magnitude”) and direction. In keeping with this definition, speed (how fast an object is going) is not rep-resented by a vector, but velocity (how fast and in which direction an object is going) does qualify as a vector quantity. Another example of a vector quantity is force, which describes how strongly and in what direction something is being pushed or pulled. But temperature, which has magnitude but no direction, is not a vector quantity. The word “vector” comes from the Latin vehere meaning “to carry;” it was first used by eighteenth-century astronomers investigating the mechanism by which a planet is “carried” around the Sun. 1 In text, the vector nature of an object is often indicated by placing a small arrow over the variable representing the object (such as F ), or by using a bold font (such as F ), or by underlining (such as F or F ∼ ). When you begin hand-writing equations involving vectors, it’s very important that you get into the habit of denoting vectors using one of these techniques (or another one of your choosing). The important thing is not how you denote vectors, it’s that you don’t simply write them the same way you write non-vector quantities. A vector is most commonly depicted graphically as a directed line seg-ment or an arrow, as shown in Figure 1.1 (a). And as you’ll see later in this section, a vector may also be represented by an ordered set of N numbers, 1 The Oxford English Dictionary . 2nd ed. 1989. 1 2 Vectors (b) (a) Figure 1.1 Graphical depiction of a vector (a) and a vector field (b). where N is the number of dimensions in the space in which the vector resides. Of course, the true value of a vector comes from knowing what it represents. - eBook - ePub

- Michael M. Mansfield, Colm O'Sullivan(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

4 Motion in two and three dimensionsAIMS

- to show how, in two and three dimensions, physical quantities can be represented by mathematical entities called vectors

- to rewrite the laws of dynamics in vector form

- to study how the laws of dynamics may be applied to bodies which are constrained to move on specific paths in two and three dimensions

- to describe how the effects of friction may be included in the analysis of dynamical problems

- to study the motion of bodies which are moving on circular paths

4.1 Vector physical quantities

The material universe is a three‐dimensional world. In our investigation of the laws of motion in Chapter 3 , however, we considered only one‐dimensional motion, that is situations in which a body moves on a straight line and in which all forces applied to the body are directed along this line of motion. If a force is applied to a body in a direction other than the direction of motion the body will no longer continue to move along this line. In general, the body will travel on some path in three‐dimensional space, the detail of the trajectory depending on the magnitude and direction of the applied force at every instant. Equation (3.3) as it stands is not sufficiently general to deal with such situations, for example the motion of a pendulum bob (Figure 4.1 ) or the motion of a planet around the Sun (Figure 4.2 ). Newton's second law needs to be generalised from the simple one‐dimensional form discussed in Chapter 3 .A pendulum comprising a mass attached to the end of a string; the mass can move on a path such that the distance from the fixed end of the string remains constant.Figure 4.1A similar problem arises if two or more forces act on a body simultaneously, for example when a number of tugs are manoeuvring a large ship (Figure 4.3

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.