Physics

Vectors in Multiple Dimensions

Vectors in multiple dimensions refer to quantities that have both magnitude and direction in a space with more than one dimension. In physics, these vectors are often used to represent physical quantities such as force, velocity, and acceleration in three-dimensional space. They are typically represented using coordinates and can be added, subtracted, and multiplied by scalars.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Vectors in Multiple Dimensions"

- No longer available |Learn more

- James Stewart, Lothar Redlin, Saleem Watson(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 630 CHAPTER 9 ■ Vectors in Two and Three Dimensions 9.1 VECTORS IN TWO DIMENSIONS ■ Geometric Description of Vectors ■ Vectors in the Coordinate Plane ■ Using Vectors to Model Velocity and Force In applications of mathematics, certain quantities are determined completely by their magnitude—for example, length, mass, area, temperature, and energy. We speak of a length of 5 m or a mass of 3 kg; only one number is needed to describe each of these quantities. Such a quantity is called a scalar. On the other hand, to describe the displacement of an object, two numbers are re- quired: the magnitude and the direction of the displacement. To describe the velocity of a moving object, we must specify both the speed and the direction of travel. Quantities such as displacement, velocity, acceleration, and force that involve magnitude as well as direction are called directed quantities. One way to represent such quantities math- ematically is through the use of vectors. ■ Geometric Description of Vectors A vector in the plane is a line segment with an assigned direction. We sketch a vector as shown in Figure 1 with an arrow to specify the direction. We denote this vector by AB > . Point A is the initial point, and B is the terminal point of the vector AB > . The length of the line segment AB is called the magnitude or length of the vector and is denoted by 0 AB > 0 . We use boldface letters to denote vectors. Thus we write u AB > . Two vectors are considered equal if they have equal magnitude and the same direction. - eBook - PDF

- David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

40 C H A P T E R 3 Vectors 3-1 VECTORS AND THEIR COMPONENTS What Is Physics? Physics deals with a great many quantities that have both size and direction, and it needs a special mathematical language — the language of vectors — to describe those quantities. This language is also used in engineering, the other sciences, and even in common speech. If you have ever given directions such as “Go five blocks down this street and then hang a left,” you have used the language of vectors. In fact, navigation of any sort is based on vectors, but physics and engineering also need vectors in special ways to explain phenomena involving rotation and mag- netic forces, which we get to in later chapters. In this chapter, we focus on the basic language of vectors. Vectors and Scalars A particle moving along a straight line can move in only two directions. We can take its motion to be positive in one of these directions and negative in the other. For a particle moving in three dimensions, however, a plus sign or minus sign is no longer enough to indicate a direction. Instead, we must use a vector. 3.01 Add vectors by drawing them in head-to-tail arrangements, applying the commutative and associa- tive laws. 3.02 Subtract a vector from a second one. 3.03 Calculate the components of a vector on a given coordinate system, showing them in a drawing. 3.04 Given the components of a vector, draw the vector and determine its magnitude and orientation. 3.05 Convert angle measures between degrees and radians. ● Scalars, such as temperature, have magnitude only. They are specified by a number with a unit (10°C) and obey the rules of arithmetic and ordinary algebra. Vectors, such as displacement, have both magnitude and direction (5 m, north) and obey the rules of vector algebra. ● Two vectors a → and b → may be added geometrically by drawing them to a common scale and placing them head to tail. The vector connecting the tail of the first to the head of the second is the vector sum s → . - eBook - PDF

- David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

34 C H A P T E R 3 Vectors 3-1 VECTORS AND THEIR COMPONENTS What Is Physics? Physics deals with a great many quantities that have both size and direction, and it needs a special mathematical language — the language of vectors — to describe those quantities. This language is also used in engineering, the other sciences, and even in common speech. If you have ever given directions such as “Go five blocks down this street and then hang a left,” you have used the language of vectors. In fact, navigation of any sort is based on vectors, but physics and engineering also need vectors in special ways to explain phenomena involving rotation and mag- netic forces, which we get to in later chapters. In this chapter, we focus on the basic language of vectors. Vectors and Scalars A particle moving along a straight line can move in only two directions. We can take its motion to be positive in one of these directions and negative in the other. For a particle moving in three dimensions, however, a plus sign or minus sign is no longer enough to indicate a direction. Instead, we must use a vector. 3.01 Add vectors by drawing them in head-to-tail arrangements, applying the commutative and associa- tive laws. 3.02 Subtract a vector from a second one. 3.03 Calculate the components of a vector on a given coordinate system, showing them in a drawing. 3.04 Given the components of a vector, draw the vector and determine its magnitude and orientation. 3.05 Convert angle measures between degrees and radians. ● Scalars, such as temperature, have magnitude only. They are specified by a number with a unit (10°C) and obey the rules of arithmetic and ordinary algebra. Vectors, such as displacement, have both magnitude and direction (5 m, north) and obey the rules of vector algebra. ● Two vectors a → and b → may be added geometrically by drawing them to a common scale and placing them head to tail. The vector connecting the tail of the first to the head of the second is the vector sum s → . - David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

C H A P T E R 3 What Is Physics? Physics deals with a great many quantities that have both size and direction, and it needs a special mathematical language—the language of vectors—to describe those quantities. This language is also used in engineering, the other sciences, and even in common speech. If you have ever given directions such as “Go five blocks down this street and then hang a left,” you have used the language of vectors. In fact, navigation of any sort is based on vectors, but physics and engineering also need vectors in special ways to explain phenomena involving rotation and magnetic forces, which we get to in later chapters. In this chapter, we focus on the basic language of vectors. Vectors and Scalars A particle moving along a straight line can move in only two directions. We can take its motion to be positive in one of these directions and negative in the other. For a particle moving in three dimensions, however, a plus sign or minus sign is no longer enough to indicate a direction. Instead, we must use a vector. After reading this module, you should be able to . . . 3.1.1 Add vectors by drawing them in head-to-tail arrangements, applying the commutative and associative laws. 3.1.2 Subtract a vector from a second one. 3.1.3 Calculate the compo- nents of a vector on a given coordinate system, showing them in a drawing. 3.1.4 Given the components of a vector, draw the vector and determine its magnitude and orientation. 3.1.5 Convert angle measures between degrees and radians. 3.1 VECTORS AND THEIR COMPONENTS LEARNING OBJECTIVES Vectors KEY IDEAS 1. Scalars, such as temperature, have magnitude only. They are specified by a num- ber with a unit (10°C) and obey the rules of arithmetic and ordinary algebra. Vectors, such as displacement, have both magnitude and direction (5 m, north) and obey the rules of vector algebra. 2. Two vectors a → and b → may be added geometrically by drawing them to a com- mon scale and placing them head to tail.- Kuldip S. Rattan, Nathan W. Klingbeil, Craig M. Baudendistel(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Two-Dimensional Vectors in Engineering CHAPTER 4 The applications of two-dimensional vectors in engineering are introduced in this chapter. Vectors play a very important role in engineering. The quantities such as displacement (position), velocity, acceleration, forces, electric and magnetic fields, and momentum have not only a magnitude but also a direction associated with them. To describe the displacement of an object from its initial point, both the distance and direction are needed. A vector is a convenient way to represent both magnitude and direction and can be described in either a Cartesian or a polar coordinate system (rectangular or polar forms). For example, an automobile traveling north at 65 mph can be represented by a two-dimensional vector in polar coordinates with a magnitude (speed) of 65 mph and a direction along the positive y-axis. It can also be represented by a vector in Cartesian coordinates with an x-component of zero and a y-component of 65 mph. The tip of the one-link and two-link planar robots introduced in Chapter 3 will be represented in this chapter using vectors both in Cartesian and polar coordinates. The concepts of unit vectors, magnitude, and direction of a vector will be introduced. 4.1 INTRODUCTION Graphically, a vector −− → OP or simply P with the initial point O and the final point P can be drawn as shown in Fig. 4.1. The magnitude of the vector is the distance between points O and P (magnitude = P) and the direction is given by the direction of the y Magnitude = P P x O θ Figure 4.1 A representation of a vector. 107 108 Chapter 4 Two-Dimensional Vectors in Engineering arrow or the angle in the counterclockwise direction from the positive x-axis as shown in Fig. 4.1. The arrow above P indicates that P is a vector. In many engineering books, the vectors are also written as a boldface P.- eBook - PDF

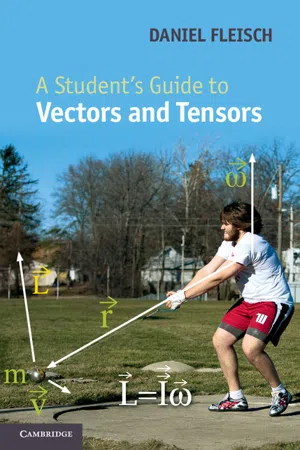

- Daniel A. Fleisch(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 Vectors 1.1 Definitions (basic) There are many ways to define a vector. For starters, here’s the most basic: A vector is the mathematical representation of a physical entity that may be characterized by size (or “magnitude”) and direction. In keeping with this definition, speed (how fast an object is going) is not rep-resented by a vector, but velocity (how fast and in which direction an object is going) does qualify as a vector quantity. Another example of a vector quantity is force, which describes how strongly and in what direction something is being pushed or pulled. But temperature, which has magnitude but no direction, is not a vector quantity. The word “vector” comes from the Latin vehere meaning “to carry;” it was first used by eighteenth-century astronomers investigating the mechanism by which a planet is “carried” around the Sun. 1 In text, the vector nature of an object is often indicated by placing a small arrow over the variable representing the object (such as F ), or by using a bold font (such as F ), or by underlining (such as F or F ∼ ). When you begin hand-writing equations involving vectors, it’s very important that you get into the habit of denoting vectors using one of these techniques (or another one of your choosing). The important thing is not how you denote vectors, it’s that you don’t simply write them the same way you write non-vector quantities. A vector is most commonly depicted graphically as a directed line seg-ment or an arrow, as shown in Figure 1.1 (a). And as you’ll see later in this section, a vector may also be represented by an ordered set of N numbers, 1 The Oxford English Dictionary . 2nd ed. 1989. 1 2 Vectors (b) (a) Figure 1.1 Graphical depiction of a vector (a) and a vector field (b). where N is the number of dimensions in the space in which the vector resides. Of course, the true value of a vector comes from knowing what it represents. - eBook - PDF

- John Gilbert, Camilla Jordan, David A Towers(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 9 Vectors By the end of this chapter you will have • been introduced to the terminology and notation of vec-tors; • used scalar and vector products; • seen triple scalar and triple vector products and their geometric interpretation; • learnt about vector functions and how to differentiate them. Aims and Objectives 9.1 Vectors Up to now we have used real numbers to represent the magnitude of physical quantities, such as mass and length, which are unrelated to any direction in space. We shall call such quantities scalars : they obey the ordinary rules of algebra. However, there are many physical quantities, such as velocity and force, which are only specified completely when a direction is given as well as a magnitude. We call such quantities vectors and we shall develop an algebra for their manipulation. In many applications we shall find that this leads to very elegant and concise solutions. When we have to apply the result to a practical situation, we usually find it necessary to describe the vectors in terms of their coordinates. For this reason, as well as to ease the derivation of algebraic rules for vectors, we start with a brief study of coordinate systems. Coordinate systems In order to measure the lengths and directions of lines, we need some kind of reference system. 205 206 Guide to Mathematical Methods x y O P ( x , y ) x y Figure 9.1: Two-dimensional coordinates In two-dimensional space, we set up mutually perpendicular axes, intersecting at an origin, O . We refer to these axes as rectangular Cartesian axes (after Descartes 1596–1650) and designate the positive directions of the axes as Ox (the x -axis) and Oy (the y -axis). The x and y coordinates of a point P are defined by the perpendicular distances, x and y , of P from Oy and Ox re-spectively, as shown in Figure 9.1. We say that P has coordinates ( x , y ). We note that the length of OP can be obtained, using Pythagoras’ Theorem, as x 2 + y 2 . - eBook - PDF

Functions Modeling Change

A Preparation for Calculus

- Eric Connally, Deborah Hughes-Hallett, Andrew M. Gleason(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Such quantities are known as vectors. Like displacements, vectors are often represented as arrows. A vector has magnitude (the arrow’s length) and direction (which way the arrow points). Examples of vectors include: • Velocity This is the speed and direction of travel. • Force This is, loosely speaking, the strength and direction of a push or a pull. • Magnetic fields A vector gives the direction and intensity of a magnetic field at a point. • Vectors in economics Vectors are used to keep track of prices and quantities. • Vectors in computer animation Computers generate animations by performing enormous numbers of vector-based calculations. • Population vectors In biology, populations of different animals or age groups can be repre- sented using vectors. Vector Notation In this book we write vectors as variables with arrows over them: . The notation is intended to ensure that a vector is not mistaken for a scalar, which is another name for an ordinary number. Notation for the Magnitude of a Vector The length or magnitude of a vector is written . This notation looks like the absolute value notation, , used for scalars. The absolute value of a number is its size without regard to sign, so −10 = +10 = 10. Similarly, the vectors and in Figure 12.4 are both of length 5, even though they point in different directions. Therefore, = = 5 (although ≠ ). 444 Chapter 12 VECTORS AND MATRICES = 5 = 5 Figure 12.4: The vectors and are both of magnitude 5, but they point in different directions Addition of Vectors As with displacements, the sum of two vectors and represented by arrows is found by joining the tail of to the head of . Then = + is represented by the arrow drawn from the tail of to the head of . - eBook - PDF

- David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

We can write a vector a → in terms of unit vectors as a → = a x ˆ i + a y ˆ j + a z k ̂ , (3.2.1) in which a x ˆ i, a y ˆ j, and a z k ̂ are the vector components of a → and a x , a y , and a z are its scalar components. Review & Summary Adding Vectors in Component Form To add vectors in component form, we use the rules r x = a x + b x r y = a y + b y r z = a z + b z . (3.2.4 to 3.2.6) Here a → and b → are the vectors to be added, and r → is the vector sum. Note that we add components axis by axis.We can then express the sum in unit-vector notation or magnitude-angle notation. Product of a Scalar and a Vector The product of a sca- lar s and a vector v → is a new vector whose magnitude is sv and whose direction is the same as that of v → if s is positive, and oppo- site that of v → if s is negative. (The negative sign reverses the vector.) To divide v → by s, multiply v → by 1/s. The Scalar Product The scalar (or dot) product of two vectors a → and b → is written a → ⋅ b → and is the scalar quantity given by a → ⋅ b → = ab cos ϕ, (3.3.1) in which ϕ is the angle between the directions of a → and b → . A sca- lar product is the product of the magnitude of one vector and the scalar component of the second vector along the direction of the first vector. Note that a → ⋅ b → = b → ⋅ a → , which means that the scalar product obeys the commutative law. In unit-vector notation, a → ⋅ b → = ( a x ˆ i + a y ˆ j + a z k ̂ ) ⋅ ( b x ˆ i + b y ˆ j + b z k ̂ ), (3.3.3) which may be expanded according to the distributive law. The Vector Product The vector (or cross) product of two vectors a → and b → is written a → × b → and is a vector c → whose mag- nitude c is given by c = ab sin ϕ, (3.3.5) in which ϕ is the smaller of the angles between the directions of a → and b → . The direction of c → is perpendicular to the plane defined by a → and b → and is given by a right-hand rule, as shown in Fig. - eBook - PDF

Calculus

Concepts and Contexts, Enhanced Edition

- James Stewart(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 648 CHAPTER 9 VECTORS AND THE GEOMETRY OF SPACE 38. Suppose a vector makes angles , , and with the positive -, -, and -axes, respectively. Find the components of and show that (The numbers , , and are called the direction cosines of .) 39. If and , describe the set of all points such that . 40. If , , and , describe the set of all points such that , where . 41. Figure 16 gives a geometric demonstration of Property 2 of vectors. Use components to give an algebraic proof of this fact for the case . 42. Prove Property 5 of vectors algebraically for the case . Then use similar triangles to give a geometric proof. 43. Use vectors to prove that the line joining the midpoints of two sides of a triangle is parallel to the third side and half its length. n 3 n 2 k r 1 r 2 r r 1 r r 2 k x , y r 2 x 2 , y 2 r 1 x 1 , y 1 r x , y r r 0 1 x , y , z r 0 x 0 , y 0 , z 0 r x , y , z a cos cos cos cos 2 cos 2 cos 2 1 a z y x a 44. Suppose the three coordinate planes are all mirrored and a light ray given by the vector first strikes the -plane, as shown in the figure. Use the fact that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection to show that the direc-tion of the reflected ray is given by . Deduce that, after being reflected by all three mutually perpendicular mirrors, the resulting ray is parallel to the initial ray. (American space scientists used this principle, together with laser beams and an array of corner mirrors on the moon, to calculate very precisely the distance from the earth to the moon.) b a z x y b a 1 , a 2 , a 3 x z a a 1 , a 2 , a 3 So far we have added two vectors and multiplied a vector by a scalar.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.