Politics & International Relations

The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, announced the thirteen American colonies' decision to break away from British rule. It outlined the principles of self-government and individual rights, asserting that all people are created equal and have the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The document served as a catalyst for the American Revolutionary War and inspired movements for independence worldwide.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

8 Key excerpts on "The Declaration of Independence"

- eBook - PDF

The Declaration of Independence

A Global History

- David Armitage(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

This list of the corporate rights of states was as open-ended as the roster of individual rights found earlier in the Declaration, which had stated that “all Men . . . are endowed by their Cre-The World in The Declaration of Independence 29 ator with certain unalienable Rights . . . among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” (my emphases). The Declaration specified the powers of states—war and peace, treaty-making, and commerce—without foreclosing the need to exercise other, similar powers should the need arise. With that precise but flexible declaration of rights, the representa-tives of the United States announced that they had left the transnational community of the British Empire to join instead an international community of independent sovereign states. The Declaration of Independence was therefore a declara-tion of interdependence. By issuing it, members of Congress showed their “Respect to the Opinions of Mankind.” They sub-mitted the facts of their case to “a candid World,” meaning an unprejudiced world. And they pledged to treat the British “as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends.” The Declaration may have spoken on behalf of Ameri-cans through the voice of their congressional representatives, but they were not the audience to which the text implicitly di-rected its argument. That was instead the “Opinions of Man-kind,” the collective public opinion of the powers of the earth. The very term “declaration” would have implied as much. To be sure, the word did have technical meanings within seven-teenth-century English history and eighteenth-century English law. Historically, a declaration was a public document issued by a representative body such as Parliament; by calling its doc-30 The World in The Declaration of Independence ument a “Declaration,” the Continental Congress implied that it possessed the same sort of power to issue such documents as did the British Parliament. - eBook - PDF

The Changing Conversation in America

Lectures from the Smithsonian

- William F. Eadie, Paul E. Nelson, William F. Eadie, Paul E. Nelson(Authors)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

THE CHANGING CONVERSATION IN AMERICA The Declaration of Independence in the Rhetoric of American Politics 3 The Declaration of Independence in the Rhetoric of American Politics STEPHEN E. LUCAS University of Wisconsin, Madison No public document other than the U.S. Constitution has played a more crucial role in American political conversation than the Declaration of In-dependence. More than a century ago, Moses Coit Tyler deemed it “the one American state paper that has reached to supreme distinction in the world, and that seems likely to last as long as American civilization lasts” (Tyler, 1897, p. 498). Tyler’s assessment is no less apposite today. Having spent a number of years studying the Declaration, I can attest both to its historical importance and its abiding hold on the public imagination. Part of my research has focused on what I call the rhetorical ancestry of the Declaration—how it was shaped by long-standing conventions of for-mal political discourse that imposed powerful constraints on the Declara-tion’s structure and content (Lucas, 1998). I have also sought to explain the Declaration’s rhetorical artistry—to demonstrate, by close analysis of the text, not only how the Declaration was adroitly composed to meet the political needs of the moment in July 1776 but also why it remains to this day an acknowledged masterpiece of political prose style (Lucas, 1989, 1990). In this chapter, I turn to a third aspect of the Declaration—its rhetor-ical legacy. By this, I mean the way the Declaration has been used in the 39 dialogue of American politics since the establishment of independence from Great Britain. During this time, the Declaration has become, in D. W. Brogan’s phrase, “the most sacred of all American political scriptures” (Detweiler, 1962, p. 557). - Thomas Jefferson(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Heritage Books(Publisher)

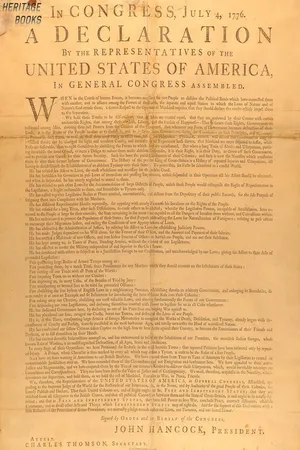

The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America

The Declaration of Independence OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICAWhen in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume, among the Powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. —Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.- eBook - PDF

The Declaration of Independence and God

Self-Evident Truths in American Law

- Owen Anderson(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Indeed, in contrast to The Declaration of Independence, the U.N.’s Declaration of Universal Human Rights overlooks any mention of God and simply starts with assertions about rights. The Declaration of Independence stands out as unique not only because of its significant impact in world history but because of how it begins. In our current study, we will fill this gap and provide much-needed research on what can arguably be said to be the most important claims in The Declaration of Independence. The Declaration of Independence has been studied from almost every perspective imaginable. So, too, have the lives and political phi- losophies of the principle contributors to that document. The present study will contribute to this by looking at the Declaration as a creed that sets forth the basic beliefs of the nation and studying how these were understood and challenged in the time since the Revolution. 16 The Declaration of Independence and God Although The Declaration of Independence is held in high esteem, it makes a startling claim that few today would actually accept. This is that some things are self-evident, and among these are that humans are created. From the claim that this Creator endows humans with rights, we can infer that this is a personal creator along the lines of theism or deism. And yet, if God exists, is it self-evident that God exists? In the following, I will explore this question and its importance for both reli- gion and law in the United States. Although events were already set in motion for a revolution by the time The Declaration of Independence was written, it states the found- ing ideas that serve to explain the origin of the new country. It is writ- ten to the world to explain why the colonists decided on independence. In order to justify their decision, it gives principles that it takes to be basic and universal. - eBook - PDF

The Last Utopia

Human Rights in History

- Samuel Moyn(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Belknap Press(Publisher)

Far from providing rationale for foreign or “human” claims against states, assertions of rights were at root—and for at least a century—a justification for states to come about. Unlike the founding documents of the Ameri-can states, The Declaration of Independence had no real list of enti-tlements in it, since it aimed primarily to achieve sovereignty exter-nally against European encroachment. 32 As a matter of fact, rights were subordinate features of the creation of both state and nation beginning in this era, for few took the trouble to distinguish them. 33 A mere decade after the Americans declared the autonomy of their new state to the world, the French in their own revolutionary decla-ration of rights insisted “the principle of all sovereignty resides es-sentially in the Nation,” adding for good measure that “no body and no individual may exercise authority which does not emanate ex-pressly from it” (Art. 3). In an era in which American popular unity Humanity before Human Rights 27 coalesced thanks as much to bloody Indian wars as to high princi-ples, it may have been simply true to stereotype for the French to identify their own national identity with universal morality; they saw no conflict in proclaiming the emergence of a sovereign nation of Frenchmen and announcing the rights of man as man at one and the same time. As a result, rights announced in the constitution of the sovereign nation-state—not “human rights” in the contemporary sense—were the great and fateful bequest of the French Revolution to world politics. No doubt, the transition to the world of potentially republican states did not simply reproduce the international affairs of a world in which empire and monarchy set the standard. The French Revolu-tion did have profound implications for the global order, imme-diately making several Enlightenment visions of “perpetual peace” seem within reach to a few. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- College Publishing House(Publisher)

Its stature grew over the years, particularly the second sentence, a sweeping statement of individual human rights: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. This sentence has been called one of the best-known sentences in the English language and the most potent and consequential words in American history. After finalizing the text on July 4, Congress issued The Declaration of Independence in several forms. It was initially published as a printed broadside that was widely distributed and read to the public. The most famous version of the Declaration, a signed copy that is usually regarded as The Declaration of Independence, is on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Although the wording of the Declaration was approved on July 4, the date of its signing has been disputed. Most historians have concluded that it was signed nearly a month after its adoption, on August 2, 1776, and not on July 4 as is commonly believed. The sources and interpretation of the Declaration have been the subject of much scholarly inquiry. The famous wording of the Declaration has often been invoked to protect the rights of individuals and marginalized groups, and has come to represent for many people a moral standard for which the United States should strive. This view greatly influenced Abraham Lincoln, who considered the Declaration to be the foundation of his political philosophy, and who promoted the idea that the Declaration is a statement of principles through which the United States Constitution should be interpreted. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Background Thomas Jefferson, the principal drafter of the Declaration, argued that Parliament was a foreign legislature that was unconstitutionally trying to extend its sovereignty into the colonies. - eBook - ePub

Self-Determination, International Law and Post-Conflict Reconstruction

A Right in Abeyance

- Manuela Melandri(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The resolution indeed proclaimed the existence of a ‘right’ of self-determination for all peoples. Paragraph 2 of the document reads: 2. All peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development. Whilst the resolution has a non-binding character, hence being not a law-making instrument in itself, its effects on the development of international law today are undisputed. 88 The Declaration has indeed influenced a highly significant number of subsequent assembly resolutions, declarations and conventions, creating a set of consistent practice and, with it, of opinio juris, around the issue of decolonisation. In brief, today it is possible to say that it was with the Declaration, in 1960, that self-determination became a right vested in the colonial peoples residing in non-self-governing territories. 89 Thus, it can be said that, at that moment in time, a new layer of self-determination was created, and that the principle acquired a new, additional meaning in international law. Here I will not analyse in detail the contribution of the Declaration to the development of international law on self-determination. This point has already been dealt with at length in other occasions and is well-established in the literature. 90 For the purposes of this study, it shall be sufficient to accomplish a much less ambitious task. Simply, in this section I wish to explain that the Declaration brings an important conceptual development in the life of self-determination as a principle of international law. Moreover, I wish to highlight how this development represents a departure from the meaning originally attributed to self-determination which was set out in the UN Charter, and that the existence of these two branches of the principle is not mutually exclusive - eBook - PDF

- David Arndt(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Politics is not possible except among citizens who are equal by law. This equality is an essential condition of a free polity. We hold the principle of equality not because it expresses a self-evident truth about human beings, but because it makes possible political freedom. That all men are created equal is not self-evident nor can it be proved. We hold this opinion because freedom is possible only among equals, and we believe that the joys and gratifications of free company are to be preferred to the doubtful pleasures of holding dominion . . . These are matters of opinion and not of truth – as Jefferson, much against his will, admitted. Their validity depends upon free agreement and consent; they are arrived at by discursive, representative thinking; and they are communicated by means of persuasion and dissuasion. OR, –. OR, . OT, . BPF, . The Declaration of Independence The validity of the principle of equality does not rest on self-evident truth but on the opinion that life in a free polity is better than life under any form of rule. “Endowed by Their Creator with Certain Unalienable Rights” The Declaration claims that all men by nature have rights. Arendt noted this claim implies a certain understanding of human nature. Rights are understood as properties that belong to the nature of each individual, just as natural substances have intrinsic and objective properties that exist in and of themselves. The idea is that positive laws can be based on natural laws, which can be derived from natural rights, which can be deduced from human nature. The very language of The Declaration of Independence as well as of the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme – “inalienable,” “given with birth,” “self- evident truths” – implies the belief in a kind of human “nature” .

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.