Technology & Engineering

Circular Functions

Circular functions are mathematical functions that are defined using the unit circle. The most common circular functions are the sine and cosine functions, which represent the y and x coordinates of points on the unit circle, respectively. These functions are widely used in technology and engineering for modeling periodic phenomena such as sound waves, alternating currents, and oscillations.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

6 Key excerpts on "Circular Functions"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Library Press(Publisher)

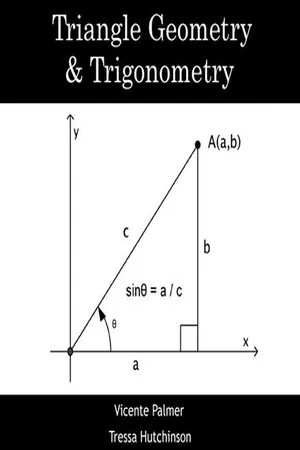

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 10 Trigonometric Functions In mathematics, the trigonometric functions (also called Circular Functions ) are fun-ctions of an angle. They are used to relate the angles of a triangle to the lengths of the sides of a triangle. Trigonometric functions are important in the study of triangles and modeling periodic phenomena, among many other applications. The most familiar trigonometric functions are the sine, cosine, and tangent. In the context of the standard unit circle with radius 1, where a triangle is formed by a ray originating at the origin and making some angle with the x -axis, the sine of the angle gives the length of the y -component (rise) of the triangle, the cosine gives the length of the x -component (run), and the tangent function gives the slope ( y -component divided by the x -comp-onent). More precise definitions are detailed below. Trigonometric functions are commonly defined as ratios of two sides of a right triangle containing the angle, and can equivalently be defined as the lengths of various line segments from a unit circle. More modern definitions express them as infinite series or as solutions of certain differential equations, allowing their extension to arbitrary positive and negative values and even to complex numbers. Trigonometric functions have a wide range of uses including computing unknown lengths and angles in triangles (often right triangles). In this use, trigonometric functions are used for instance in navigation, engineering, and physics. A common use in elementary physics is resolving a vector into Cartesian coordinates. The sine and cosine functions are also commonly used to model periodic function phenomena such as sound and light waves, the position and velocity of harmonic oscillators, sunlight intensity and day length, and average temperature variations through the year. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 3 Trigonometric Functions In mathematics, the trigonometric functions (also called Circular Functions ) are func-tions of an angle. They are used to relate the angles of a triangle to the lengths of the sides of a triangle. Trigonometric functions are important in the study of triangles and modeling periodic phenomena, among many other applications. The most familiar trigonometric functions are the sine, cosine, and tangent. In the context of the standard unit circle with radius 1, where a triangle is formed by a ray originating at the origin and making some angle with the x -axis, the sine of the angle gives the length of the y -component (rise) of the triangle, the cosine gives the length of the x -component (run), and the tangent function gives the slope ( y -component divided by the x -component). More precise definitions are detailed below. Trigonometric functions are commonly defined as ratios of two sides of a right triangle containing the angle, and can equivalently be defined as the lengths of various line segments from a unit circle. More modern definitions express them as infinite series or as solutions of certain differential equations, allowing their extension to arbitrary positive and negative values and even to complex numbers. Trigonometric functions have a wide range of uses including computing unknown lengths and angles in triangles (often right triangles). In this use, trigonometric functions are used for instance in navigation, engineering, and physics. A common use in elementary physics is resolving a vector into Cartesian coordinates. The sine and cosine functions are also commonly used to model periodic function phenomena such as sound and light waves, the position and velocity of harmonic oscillators, sunlight intensity and day length, and average temperature variations through the year. - eBook - PDF

- Bernard Kolman, Arnold Shapiro(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER FIVE TRIGONOMETRY: THE Circular Functions The word trigonometry derives from the Greek, meaning measure-ment of triangles. The conventional approach to the subject matter of trigonometry deals with relationships between the sides and angles of a triangle, reflecting the important applications of trigonometry in such fields as navigation and surveying. The modern approach is to deal with trigonometry in terms of functional relationships. The trigonometric functions can be viewed as functions whose domains are angles, or as functions whose domains are real num-bers, in which case they are often referred to as the Circular Functions. We will take the latter approach since it more clearly demonstrates the utility of the function concept. We will devote this chapter to the circular func-tions and will deal with both angles and triangles in the next chapter. We need to recall various facts from plane geometry about the circle. A line segment joining the center of a circle to any point on the circle is called a radius. Since every point on the circle is the same distance from the center, the radii of a circle are all equal. Thus, in Figure 1, OP = OQ. A chord of a circle is a line segment joining any two points on the circle; a 195 196 TRIGONOMETRY: THE Circular Functions FIGURE 1 diameter of a circle is a chord that passes through the center of the circle. Note that the length of a diameter is twice that of a radius. The circumference C of a circle is the distance around the circle and is given by C = 2irr where r is the radius of the circle. The constant 77 is then seen to be the ratio of the circumference of a circle to the length of its diameter. The area A of a circle of radius r is given by A=wr 2 An arc of a circle is simply a part of a circle. The arc AB of Figure 2 consists of the two endpoints A and B and the set of all points on the circle that are between A and B. - eBook - ePub

- Huw Fox, William Bolton(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

odd function is defined as one which has:An even function has:Cyclic functions

A cyclic function is one which repeats itself on a cyclic period. Thus, if we have a function y = f (x ) which is cyclic and repeats itself after a time T , then:[19]T is termed the periodic time and is the time taken to complete one cycle. Hence, if the frequency is f then f cycles are completed each second and so T = 1/f .As the arm OP in Figure 1.35 rotates round-and-round its circular path, the values of its vertical projection NP is cyclic and generates the sine graph shown. Since the graph describes a periodic function of period 2π, then:[20]where n = 0, ±1, ±2, etc.Figure 1.35 Graph of y = sin θNote that if OP rotates in a clockwise direction, i.e. the negative direction, then as θ is negative, this generates the sine function continued to the left of the origin O into the negative region (Figure 1.36 ). For negative values of θ, the sine function has the same values as the positive values except for a change in sign:To obtain the graph of cos θ as the radial arm OP rotates round-and-round its circular path, we read off the values of its horizontal projection ON. Figure 1.37 shows the result. Since the graph describes a periodic function of period 2π, then:Figure 1.36 Sine graph for negative anglesFigure 1.37 Graph of y = cos θ[21]where n = 0, ±1, ±2, etc.Note that the graph of y = sin θ is the same as that of y = cos θ moved ½π to the right, while that of y = cos θ is the same as y = sin θ moved ½π to the left, i.e. sin θ = cos (θ − ½π) and cos θ = sin (θ + ½π).In the projections of the radial arm OP to generate the sine or cosine graphs, we have let OP have the value of 1. If we consider a radial arm of length A , we have the same function but multiplied by A , i.e. y = A sin θ. The amplitude of the waveform is changed. To illustrate this look at the following functions and their graphs as plotted to the same scale and on the same axes (Figure 1.38 ): y = 1 sin θ with amplitude A = 1, y = 4 sin θ with amplitude A = 4 and y = 0.5 sin θ with amplitude A - eBook - PDF

- Mary Jane Sterling(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- For Dummies(Publisher)

2 Trigonometric Functions IN THIS PART . . . Define the basic trig functions using the lengths of the sides of a right triangle. Determine the relationships between the trig cofunctions and their shared sides. Extend your scope to angles greater than 90 degrees using the unit circle. Investigate the ins and outs of the domains and ranges of the six trig functions. Use reference angles to compute trig functions. Apply trig functions to real-world problems. CHAPTER 6 Describing Trig Functions 91 Chapter 6 Describing Trig Functions B y taking the lengths of the sides of right triangles or the chords of circles and creating ratios with those numbers and variables, our ancestors initi- ated the birth of trigonometric functions. These functions are of infinite value, because they allow you to use the stars to navigate and to build bridges that won’t fall. If you’re not into navigating a boat or engineering, then you can use the trig functions at home to plan that new addition. And they’re a staple for students going into calculus. You may be asking, “What is a function? What does it have to do with trigonom- etry?” In mathematics, a function is a mechanism that takes a value you input into it and churns out an answer, called the output. A function is connected to rules involving mathematical operations or processes. The six trig functions require one thing of you — inputting an angle measure — and then they output a number. These outputs are always real numbers, from infinitely small to infinitely large and everything in between. The results you get depend on which function you use. Although in earlier times, some of the function computations were rather tedious, today’s hand-held calculators, and even phones, make everything much easier. IN THIS CHAPTER » Understanding the three basic trig functions » Building on the basics: The reciprocal functions » Recognizing the angles that give the cleanest trig results » Determining the exact values of functions - eBook - PDF

- Doug French(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Continuum(Publisher)

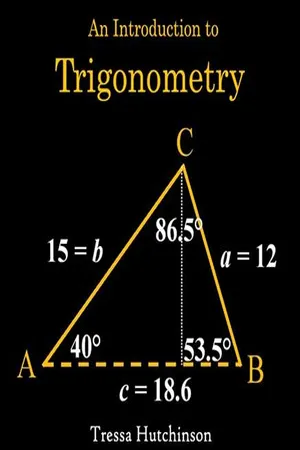

Chapter 10 Trigonometry and Circular Functions In every right triangle, if we describe a circle with a centre a vertex of an acute angle and radius the length of the longest side, then the side subtending this acute angle is the right sine of the arc adjacent to that side and opposite the given angle; the third side is equal to the sine of the complement of the arc. (Regiomontanus (1436-1476) in Fauvel and Gray, 1987, p. 245) INTRODUCING SINE AND COSINE The geometrical task of finding lengths and angles in triangles requires familiarity with the Circular Functions -sine, cosine and tangent -whose role in mathematics is extensive and important, going way beyond the solution of triangles that originally inspired their develop-ment. Understanding the properties of these functions and their application to a variety of problems requires an interplay between geometric and algebraic ideas. Unfortunately, students often come to regard the subject as difficult, seeing it as a matter of remembering a lot of apparently unrelated formulae and procedures. It is essential to develop an understanding of how the three functions relate to right-angled triangles and then, as they are developed further, to appreciate the link to circles, the behaviour and properties of their graphs and the con-nections between identities as a web of interrelated ideas rather than as a set of disparate facts. Many school textbooks, working with right-angled triangles, define sine, cosine and tangent initially as ratios, which, as has been pointed out in Chapter 8, is an idea that students often find difficult. A ratio provides a comparison between two numbers and is not necessarily itself seen as a number that can be interpreted, in particular, as a length. In fact, a length is a ratio because there is an implicit comparison with whatever is being taken as the unit of measure-ment. However, students think of lengths as something simple and concrete that can be represented by numbers.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.