Technology & Engineering

Unit Vector

A unit vector is a vector with a magnitude of 1, often used to indicate direction. In engineering and technology, unit vectors are essential for representing and manipulating directional information in three-dimensional space. They are commonly used in fields such as computer graphics, robotics, and physics to describe forces, velocities, and orientations.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Unit Vector"

- Kuldip S. Rattan, Nathan W. Klingbeil, Craig M. Baudendistel(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Two-Dimensional Vectors in Engineering CHAPTER 4 The applications of two-dimensional vectors in engineering are introduced in this chapter. Vectors play a very important role in engineering. The quantities such as displacement (position), velocity, acceleration, forces, electric and magnetic fields, and momentum have not only a magnitude but also a direction associated with them. To describe the displacement of an object from its initial point, both the distance and direction are needed. A vector is a convenient way to represent both magnitude and direction and can be described in either a Cartesian or a polar coordinate system (rectangular or polar forms). For example, an automobile traveling north at 65 mph can be represented by a two-dimensional vector in polar coordinates with a magnitude (speed) of 65 mph and a direction along the positive y-axis. It can also be represented by a vector in Cartesian coordinates with an x-component of zero and a y-component of 65 mph. The tip of the one-link and two-link planar robots introduced in Chapter 3 will be represented in this chapter using vectors both in Cartesian and polar coordinates. The concepts of Unit Vectors, magnitude, and direction of a vector will be introduced. 4.1 INTRODUCTION Graphically, a vector −− → OP or simply P with the initial point O and the final point P can be drawn as shown in Fig. 4.1. The magnitude of the vector is the distance between points O and P (magnitude = P) and the direction is given by the direction of the y Magnitude = P P x O θ Figure 4.1 A representation of a vector. 107 108 Chapter 4 Two-Dimensional Vectors in Engineering arrow or the angle in the counterclockwise direction from the positive x-axis as shown in Fig. 4.1. The arrow above P indicates that P is a vector. In many engineering books, the vectors are also written as a boldface P.- David Halliday, Jearl Walker, Patrick Keleher, Paul Lasky, John Long, Judith Dawes, Julius Orwa, Ajay Mahato, Peter Huf, Warren Stannard, Amanda Edgar, Liam Lyons, Dipesh Bhattarai(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Given a vector’s components, we can fnd the magnitude and orientation of the vector a with a = √ a 2 x + a 2 y and tan = a y a x . Why study physics? Physics deals with a great many quantities that have both size and direction, and it needs a special mathematical language — the language of vectors — to describe those quantities. This language is also used in engineering, the other sciences and even in common speech. If you have ever given directions such as ‘Go five blocks down this street and then hang a left,’ you have used the language of vectors. In fact, navigation of any sort is based on vectors, but physics and engineering also need vectors in special ways to explain phenomena involving rotation and magnetic forces, which we get to in later chapters. In this chapter, we focus on the basic language of vectors. Pdf_Folio:30 Vectors and scalars A particle moving along a straight line can move in only two directions. We can take its motion to be positive in one of these directions and negative in the other. However, for a particle moving in three dimensions, a plus sign or minus sign is no longer enough to indicate a direction. Instead, we must use a vector. 1. Vector. It has magnitude (size) and direction. 2. Vector quantity. Any quantity such as displacement that has magnitude and direction. 3. Scalar quantity. Any quantity such as temperature that has magnitude but no direction. A temperature might have a plus or minus sign but certainly does not point. You have a certain body temperature, but if that compelled you to point in a certain direction, your pointing would be comical. Displacement vector FIGURE 3.1 A particle undergoing displacement from A to B. A B When a particle changes its position by moving from A to B as in figure 3.1, we say that it undergoes a displacement from A to B, which we represent with an arrow pointing directly from A to B..- eBook - PDF

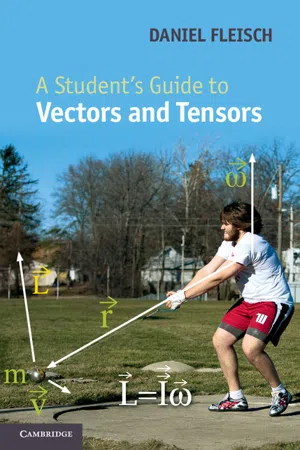

- Daniel A. Fleisch(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 Vectors 1.1 Definitions (basic) There are many ways to define a vector. For starters, here’s the most basic: A vector is the mathematical representation of a physical entity that may be characterized by size (or “magnitude”) and direction. In keeping with this definition, speed (how fast an object is going) is not rep-resented by a vector, but velocity (how fast and in which direction an object is going) does qualify as a vector quantity. Another example of a vector quantity is force, which describes how strongly and in what direction something is being pushed or pulled. But temperature, which has magnitude but no direction, is not a vector quantity. The word “vector” comes from the Latin vehere meaning “to carry;” it was first used by eighteenth-century astronomers investigating the mechanism by which a planet is “carried” around the Sun. 1 In text, the vector nature of an object is often indicated by placing a small arrow over the variable representing the object (such as F ), or by using a bold font (such as F ), or by underlining (such as F or F ∼ ). When you begin hand-writing equations involving vectors, it’s very important that you get into the habit of denoting vectors using one of these techniques (or another one of your choosing). The important thing is not how you denote vectors, it’s that you don’t simply write them the same way you write non-vector quantities. A vector is most commonly depicted graphically as a directed line seg-ment or an arrow, as shown in Figure 1.1 (a). And as you’ll see later in this section, a vector may also be represented by an ordered set of N numbers, 1 The Oxford English Dictionary . 2nd ed. 1989. 1 2 Vectors (b) (a) Figure 1.1 Graphical depiction of a vector (a) and a vector field (b). where N is the number of dimensions in the space in which the vector resides. Of course, the true value of a vector comes from knowing what it represents. - eBook - PDF

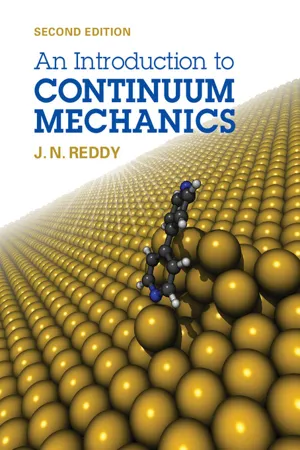

- J. N. Reddy(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

2.2.1 Definition of a Vector The quantities encountered in analytical descriptions of physical phenomena may be classified into two groups according to the information needed to specify them completely: scalars and nonscalars. The scalars are given by a single number. Nonscalars have not only a magnitude specified, but also additional information, such as direction. Nonscalars that obey certain rules (such as the parallelogram law of addition) are called vectors . Not all nonscalar quantities are vectors (e.g., a finite rotation is not a vector). A physical vector is often shown as a directed line segment with an arrow-head at the end of the line. The length of the line represents the magnitude of the vector and the arrow indicates the direction. Thus, a physical vector, possessing magnitude, is known as a normed vector space . In written material, it is customary to place an arrow over the letter denoting the physical vector, such as ~ A . In printed material the vector letter is commonly denoted by a boldface letter, A , such as is used in this book. The magnitude of the vector A , to be formally defined shortly, is denoted by | A | or A . The magnitude of a vector is a scalar. A vector of unit length is called a Unit Vector . The Unit Vector along A may be defined as follows: ˆ e A = A | A | = A A . (2 . 2 . 1) We may now write a vector A as A = A ˆ e A . (2 . 2 . 2) Thus, any vector may be represented as a product of its magnitude and a Unit Vector along the vector. A Unit Vector is used to designate direction; it does not have any physical dimensions. However, | A | has the physical dimensions. A “hat” (caret) above the boldface letter, ˆ e , is used to signify that it is a vector of unit magnitude. A vector of zero magnitude is called a zero vector or a null vector , and denoted by boldface zero, 0 . Note that a lightface zero, 0, is a scalar and boldface zero, 0 , is the zero vector. Also, a zero vector has no direction associated with it. - eBook - PDF

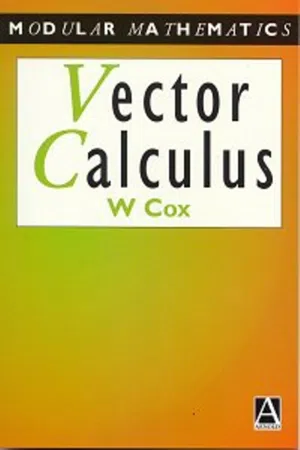

- William Cox(Author)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

8.1 Introduction: what is a vector? You are probably aware from your previous mathematics that one of the most powerful tools for dealing with functions of more than one variable is the use of vector notation. Thus, when describing the motion of a projectile in two dimen-sions we have the option of using (x(t), yet)) coordinates to represent position at any time or of using the position vector ret) = x(t)i + y(t)j with i, j the usual basis vectors. The point about using vectors here is that it effec-tively reduces the number of 'variables' -instead of two coordinates, we have one vector. A natural question therefore is to what extent one can use vectors in the theory of functions of several variables -which is what this book is about. So far, we have managed virtually without them -and indeed it is not always clear that they would be of much use. But in fact they are -the bulk of the rest of this book is essentially about 'vector calculus'. Why should this be so? Why does most of the differen-tiation and integration that we cover occur in a vector context? Is it just the case that vectors are simply a good shorthand notation whenever we have more than one variable? No, there is a deep significance to the idea of a vector which is simply not brought out in the introductory treatments to which you may have been exposed so far. Vectors are of fundamental importance and utility in all physical applications -they are far more than simply a shorthand notation. The reason for this is rather subtle, and requires a leap into abstraction which really has to be deferred until sufficient mathematical foundations have been laid -that is why elementary treatments are usually incomplete. To get an insight into the new view-point, let us stick with our two-dimensional projectile. You may have a number of different definitions, but they are most likely to come from the following list: 1. Any quantity having both a magnitude and a direction, such as velocity as opposed to speed. - eBook - PDF

- Stephen Lee(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

17 Use of vectors This grand book – the Universe… is written in the language of mathematics Galileo Galilei (1623) Vectors are important in modelling and solving two- and three-dimensional problems in mechanics. You have already used vector methods. This chapter will help you to review and consolidate your knowledge of vectors with particular reference to their application in mechanics. 17.1 Vector basics A vector is a quantity with both magnitude (also known as length, size or modulus) and direction. In mechanics, vectors are used to represent quantities such as displacement, velocity, acceleration, force and momentum. A vector is usually written PQ ⎯→ or a and is typeset as PQ ⎯→ or as bold PQ or a . In figure 17.1, PQ ⎯→ QA ⎯→ because their lengths and directions are the same. Figure 17.1 Vectors can be added: a b c and subtracted: a b d and multiplied by a scalar: a has magnitude magnitude of a . Figure 17.2 The length of the vector a is denoted a or a . When a 1, a is a Unit Vector . A Unit Vector is denoted by having a hat a . The position vector of a point A relative to a point O is the vector OA ⎯→ . Normally, O is the origin of Cartesian axes and the position vector of a point is usually denoted by the corresponding lower-case letter, thus OA ⎯→ a , OB ⎯→ b , and so on. Then AB ⎯→ b a , a d c 2 a a a b b P Q Q A a a 378 AN INTRODUCTION TO MATHEMATICS FOR ENGINEERS : MECHANICS where b and a are the position vectors of A and B with respect to an assumed origin (figure 17.3) which is not necessarily drawn on the diagram. AB ⎯→ OA ⎯→ OB ⎯→ OA ⎯→ OB ⎯→ a b b a Figure 17.3 Cartesian components Vectors can also be expressed in Cartesian component form, with respect to some appropriate origin and axes. In three dimensions: OA ⎯→ x i y i z k where a , y , z are the displacements represented by the vector in the x , y and z directions and i , j and k are the Unit Vectors in the directions of the co-ordinate axes. - David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

After reading this module, you should be able to . . . 3.2.1 Convert a vector between magnitude- angle and unit-vector notations. 3.2.2 Add and subtract vectors in magnitude- angle notation and in unit-vector notation. 3.2.3 Identify that, for a given vector, rotating the coordinate system about the origin can change the vector’s components but not the vector itself. 3.2 Unit VectorS, ADDING VECTORS BY COMPONENTS LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY IDEAS 1. Unit Vectors ˆ i, ˆ j, and k ̂ have magnitudes of unity and are directed in the pos- itive directions of the x, y, and z axes, respectively, in a right-handed coordi- nate system. We can write a vector a → in terms of Unit Vectors as a → = a x ˆ i + a y ˆ j + a z k ̂ , in which a x i ̂ , a y ˆ j, and a z k ̂ are the vector components of a → and a x , a y , and a z are its scalar components. 2. To add vectors in component form, we use the rules r x = a x + b x r y = a y + b y r z = a z + b z . Here a → and b → are the vectors to be added, and r → is the vector sum. Note that we add components axis by axis. Unit Vectors A Unit Vector is a vector that has a magnitude of exactly 1 and points in a partic- ular direction. It lacks both dimension and unit. Its sole purpose is to point—that is, to specify a direction. The Unit Vectors in the positive directions of the x, y, and z axes are labeled i ̂ , j ̂ , and k ̂ , where the hat ^ is used instead of an overhead arrow as for other vectors (Fig. 3.2.1). The arrangement of axes in Fig. 3.2.1 is said to be a right-handed coordinate system. The system remains right-handed if it is rotated rigidly. We use such coordinate systems exclusively in this book. Unit Vectors are very useful for expressing other vectors; for example, we can express a → and b → of Figs. 3.1.7 and 3.1.8 as a → = a x ˆ i + a y ˆ j (3.2.1) and b → = b x ˆ i + b y ˆ j. (3.2.2) These two equations are illustrated in Fig. 3.2.2. The quantities a x ˆ i and a y ˆ j are vectors, called the vector components of a → .- eBook - PDF

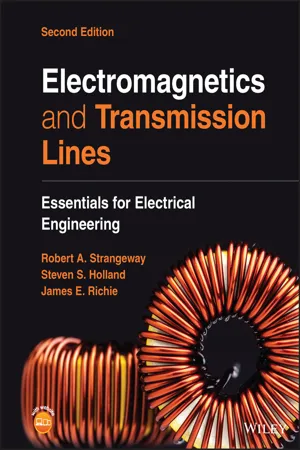

Electromagnetics and Transmission Lines

Essentials for Electrical Engineering

- Robert Alan Strangeway, Steven Sean Holland, James Elwood Richie(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

1 Vectors, Vector Algebra, and Coordinate Systems CHAPTER MENU 1.1 Vectors, 1 1.2 Vector Algebra, 4 1.2.1 Dot Product, 4 1.2.2 Cross Product, 7 1.3 Field Vectors, 10 1.4 Cylindrical Coordinate System, Vectors, and Conversions, 12 1.4.1 Cartesian (Rectangular) Coordinate System: Review, 12 1.4.2 Cylindrical Coordinate System, 13 1.5 Spherical Coordinate System, Vectors, and Conversions, 19 1.6 Summary of Coordinate Systems and Vectors, 25 1.7 Homework, 27 Motivation Why spend a chapter on vectors? The degree to which you master the vector concepts and techniques in this chapter will generally determine the degree to which you understand and can apply the essential concepts and techniques of electromagnetic fields. Vectors are not just important tools in the calculation of electromagnetic field quantities. They are essential in the visualization of electromagnetic fields in an organized, dependable man- ner. In short, a mastery of vectors instills the “thought infrastructure” that allows one to visualize and apply elec- tromagnetic fields in electrical engineering applications. Enjoy! 1.1 Vectors This chapter develops the tools necessary to define and manipulate various types of vectors in three different coor- dinate systems. We begin with how vectors can be used to describe location and displacement. What is a vector? It is a quantity with magnitude (scalar) and direction. What are examples of vectors? Velocity, force, acceleration, and so forth. How is direction in three-dimensions expressed? Start with the following vector definition: A position vector r locates a position in space with respect to the origin, that is, it is a vector that starts at the origin and ends at the point of the designated position in space (notation r is also used in some textbooks and literature). 1 Electromagnetics and Transmission Lines: Essentials for Electrical Engineering, Second Edition. Robert A. Strangeway, Steven S. Holland, and James E. - eBook - PDF

Mathematical Methods for Physicists

A Concise Introduction

- Tai L. Chow(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 Vector and tensor analysis Vectors and scalars Vector methods have become standard tools for the physicists. In this chapter we discuss the properties of the vectors and vector fields that occur in classical physics. We will do so in a way, and in a notation, that leads to the formation of abstract linear vector spaces in Chapter 5. A physical quantity that is completely specified, in appropriate units, by a single number (called its magnitude) such as volume, mass, and temperature is called a scalar. Scalar quantities are treated as ordinary real numbers. They obey all the regular rules of algebraic addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and so on. There are also physical quantities which require a magnitude and a direction for their complete specification. These are called vectors if their combination with each other is commutative (that is the order of addition may be changed without aecting the result). Thus not all quantities possessing magnitude and direction are vectors. Angular displacement, for example, may be characterised by magni-tude and direction but is not a vector, for the addition of two or more angular displacements is not, in general, commutative (Fig. 1.1). In print, we shall denote vectors by boldface letters (such as A ) and use ordin-ary italic letters (such as A ) for their magnitudes; in writing, vectors are usually represented by a letter with an arrow above it such as ~ A . A given vector A (or ~ A ) can be written as A A ^ A ; 1 : 1 where A is the magnitude of vector A and so it has unit and dimension, and ^ A is a dimensionless Unit Vector with a unity magnitude having the direction of A . Thus ^ A A = A . 1 A vector quantity may be represented graphically by an arrow-tipped line seg-ment. The length of the arrow represents the magnitude of the vector, and the direction of the arrow is that of the vector, as shown in Fig. - eBook - PDF

- William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff Sanny(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

In two dimensions (in a plane), vectors have two components. In three dimensions (in space), vectors have three components. • A vector component of a vector is its part in an axis direction. The vector component is the product of the Unit Vector of an axis with its scalar component along this axis. A vector is the resultant of its vector components. • Scalar components of a vector are differences of coordinates, where coordinates of the origin are subtracted from end point coordinates of a vector. In a rectangular system, the magnitude of a vector is the square root of the sum of the squares of its components. • In a plane, the direction of a vector is given by an angle the vector has with the positive x-axis. This direction angle is measured counterclockwise. The scalar x-component of a vector can be expressed as the product of its magnitude with the cosine of its direction angle, and the scalar y-component can be expressed as the product of its magnitude with the sine of its direction angle. • In a plane, there are two equivalent coordinate systems. The Cartesian coordinate system is defined by Unit Vectors i ^ and j ^ along the x-axis and the y-axis, respectively. The polar coordinate system is defined by the radial Unit Vector r ^ , which gives the direction from the origin, and a Unit Vector t ^ , which is perpendicular (orthogonal) to the radial direction. 2.3 Algebra of Vectors • Analytical methods of vector algebra allow us to find resultants of sums or differences of vectors without having to draw them. Analytical methods of vector addition are exact, contrary to graphical methods, which are approximate. • Analytical methods of vector algebra are used routinely in mechanics, electricity, and magnetism. They are important mathematical tools of physics. 2.4 Products of Vectors • There are two kinds of multiplication for vectors. One kind of multiplication is the scalar product, also known as the dot product.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.