What is Afrofuturism?

MSt, Women's, Gender & Sexuality Studies (University of Oxford)

Date Published: 16.03.2023,

Last Updated: 19.07.2024

Share this article

Defining Afrofuturism

You are watching the movie Black Panther (Coogler, 2018). As Fulani singer Baaba Maal vocalizes, T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman), Nakia (Lupita Nyong’o), and Okoye (Danai Gurira) fly their advanced aircraft, the Talon Fighter, low over rural Africa, dotted with galloping animals and waving shepherds. The Fighter soars toward a mountainside which suddenly diffuses into blue energy as the craft moves through a forcefield-like barrier. The music swells, and a gleaming city appears. This is Birnin Zana, the Golden City. This is Wakanda. This is Afrofuturism.

Afrofuturism imagines possible futures through a Black cultural lens. Mark Dery coined the term in Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture. In “Black to the Future,” a chapter featuring interviews with writers/cultural critics Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose, Dery writes,

Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and address African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century technoculture — and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future — might, for want of a better term, be called “Afrofuturism". (1994)

Mark Dery

Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and address African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century technoculture — and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future — might, for want of a better term, be called “Afrofuturism". (1994)

Although Dery was writing in the 1990s in response to Black American science fiction, Afrofuturism was soon understood as a broader movement, stretching back decades and beyond the realm of literature to embrace other disciplines, technologies, and cultures around the world.

Afrofuturism takes up the radical task of imagining futures for Black life, responding to the question: “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of history, imagine possible futures?” (Dery, 1994). Afrofuturists answer with a resounding yes.

In envisioning Black futures, Afrofuturism resists the ways that Black people have been historically and systemically denied futures of their own making. The lack of Black and Brown bodies, let alone fully realized Black and Brown characters, in most science fiction is apparent and alarming. Acclaimed sci-fi/fantasy writer N.K. Jemesin addresses this unsettling lack when she describes watching reruns of The Jetsons (1962–1963) as an adult:

[T]here’s nobody even slightly brown in the Jetsons’ world. Even the family android sounds white. This is supposed to be the real world’s future, right? [...] Thing is, not-white-people make up most of the world’s population, now as well as back in the Sixties when the show was created. So what happened to all those people, in the minds of this show’s creators? [...] I’m watching the Jetsons, and it’s creeping me right the fuck out. (2013)

Afrofuturism provides an alternative to the “unreal estate of the future already owned by the technocrats, futurologists, streamliners, and set designers — white to a man — who have engineered our collective fantasies” (Dery, 1994).

As Afrofuturists work to decolonize the future, they also excavate the past. In the words of Tricia Rose, “If you’re going to imagine yourself in the future, you have to imagine where you’ve come from” (Dery, 1994). In reclaiming a lost history or imagining an alternative one, Afrofuturists often incorporate African traditions, imagery, and mythologies.

Ytasha L. Womack summarizes the Afrofuturist mission in Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture:

Afrofuturists sought to unearth the missing history of people of African descent and their roles in science, technology, and science fiction. They also aimed to reintegrate people of color into the discussion of cyberculture, modern science, technology, and sci-fi pop culture. (2013)

Ytasha L. Womack

Afrofuturists sought to unearth the missing history of people of African descent and their roles in science, technology, and science fiction. They also aimed to reintegrate people of color into the discussion of cyberculture, modern science, technology, and sci-fi pop culture. (2013)

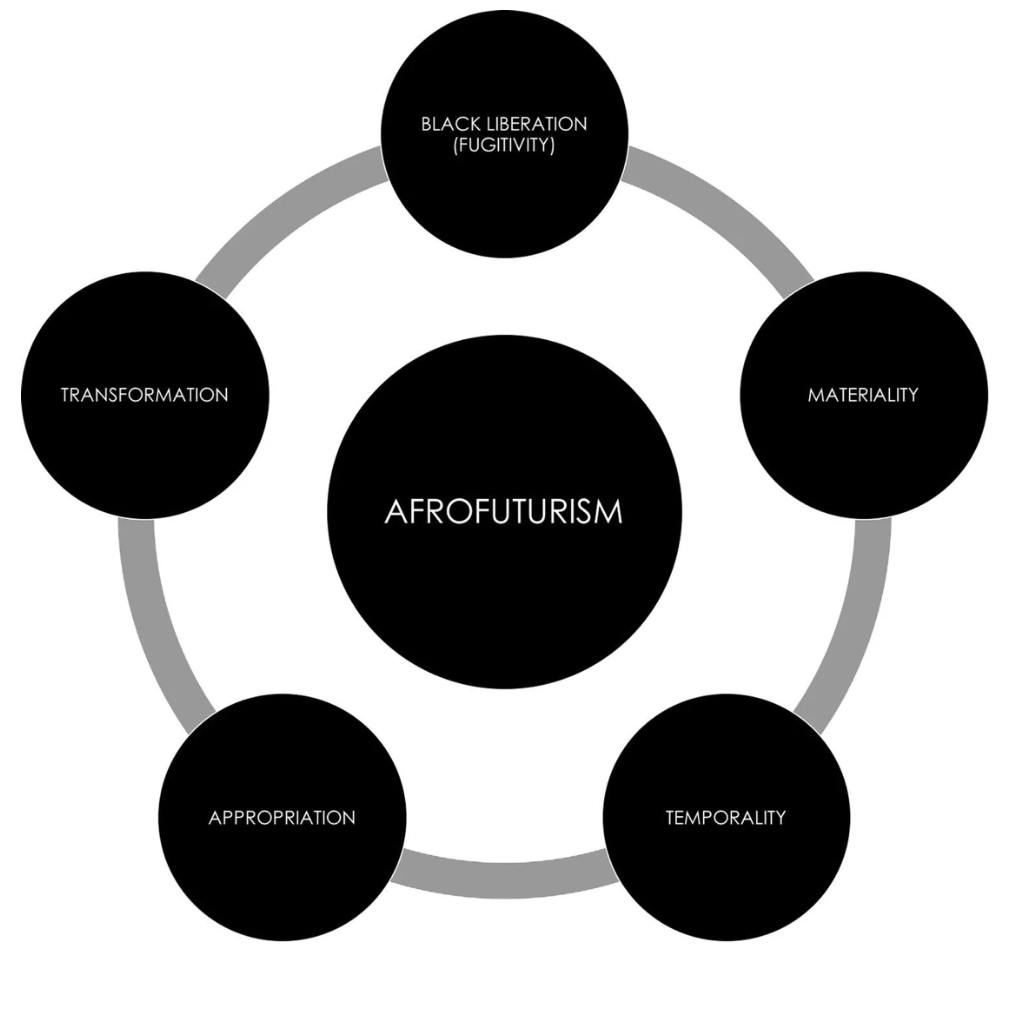

The Afrofuturist movement thus sits at “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation” (Womack, 2013). In Charting the Afrofuturist Imaginary in African American Art, Elizabeth C. Hamilton visually represents Afrofuturism. Designed with visual art in mind, her graph proves useful for understanding a broader Afrofuturist aesthetic and intention:

Elizabeth C. Hamilton, The Visual Language of Afrofuturism, 2021.

Afrofuturism combines these interests — materiality, temporality, appropriation, transformation, and black liberation (fugitivity) — while it “attends to technology, fantasy, reinterpreted pasts, and visions of the future” (Hamilton, 2022).

Afrofuturism is a cultural movement — an aesthetic, a philosophy, a practice — which constructs an expansively imaginative future while recovering and relying upon the past. Afrofuturist speaker and art curator Ingrid LaFleur describes Afrofuturism as an “intersectional, multi-temporal, multi-dimensional, and interdisciplinary approach to the future” which “empowers Black bodies to craft destinies and realities of inclusion, health, joy, and prosperity using speculative modalities such as science fiction, surrealism, magical realism, and horror.”

In crafting destinies and realities, Afrofuturism predicts Black life in the future while celebrating Black cultures, technologies, and innovations of the past and present.

Why speculative fiction?

While Afrofuturism appears across art forms and disciplines, Dery named the movement in the 1990s in response to science fiction written by Black authors. Sci-fi, at least commercially, had largely been dominated by white, male writers. Samuel R. Delany, Octavia Butler, Steve Barnes, and Charles Saunders were leading disrupters of this pattern. These writers populated the future with Black and Brown people (itself a radical act) and harnessed speculative fiction as a staging ground for ideas of Black liberation.

Afrofuturist efforts to imagine the future are inextricably linked to a history of cultural destruction. Delany says, “The historical reason that we’ve been so impoverished in terms of future images is because, until fairly recently, as a people we were systematically forbidden any images of our past” (Dery, 1994). Slavery sought to eliminate a sense of African social consciousness. Enslaved peoples were forcibly taken from their homelands, refused their language and cultural practices, separated from their peoples and relatives, barred from tools to disseminate histories, and prohibited from building families.

Speculative fiction, and science fiction in particular, is especially suited to expressing this experience. Dery is one of many scholars to draw a parallel between enslavement and alien abduction:

African-Americans, in a very real sense, are the descendents of alien abductees; they inhabit a science-fiction nightmare in which unseen but no less impassable force fields of intolerance frustrate their movements; official histories undo what has been done; and technology is too often brought to bear on black bodies. (1994)

Greg Tate argues that science fiction, through stories of people transported from the past to the future or thrust into alien cultures, parallels the sense of alienation experienced by the Black subject in the United States: “Black people live the estrangement that science fiction writers imagine” (Dery, 1994).

Moreover, as Dery contends, “the sublegitimate status of science fiction as a pulp genre in Western literature mirrors the subaltern position” to which Black people have been relegated throughout American history (1994). Delany, Womack, and Scott Bukatman place comics alongside sci-fi proper as another “sublegitimate” art form turned to by Black creators (see, as just one example, the creators and comics of Milestone Media).

Beyond reflecting the reality of lived experiences, speculative fiction enables the imagining of alternative pasts and futures. Afrofuturism pushes the boundaries of what is possible, generating new ways of thinking and being. As Bukatman writes in Black Panther (2022),

Afrofuturist entertainment is also utopian in its profligate liberatory strategies and energies, its possible futures often predicated (explicitly or not) upon alternative histories, its practitioners repurposing existent culture to their own ends, building and unleashing something new. (2020)

Scott Bukatman

Afrofuturist entertainment is also utopian in its profligate liberatory strategies and energies, its possible futures often predicated (explicitly or not) upon alternative histories, its practitioners repurposing existent culture to their own ends, building and unleashing something new. (2020)

Speculative fiction provides the tools for building a new world, constructing new histories and futures, and shattering impossibilities. Afrofuturism harnesses that power in the name of liberation.

A history of Afrofuturism

Black utopian thought has a long history, dating back to Martin R. Delany’s political writings on Black nationalism and his fictional dramatization of those ideas in Blake; or the Huts of America (1859) — what Alex Zamalin calls in Black Utopia “the first work of Black fantasy fiction” (2019). As Black utopian thought developed, speculative fiction remained a useful tool for exploring its possibilities. W. E. B. Du Bois’s short story “The Comet” (1920) asked how race would matter after the apocalypse, and his novel Dark Princess (1928) visualized a utopian Global South in which people of color united for collective self-determination (Zamalin, 2019).

Many histories of Afrofuturism begin with Sun Ra, the jazz composer, musician, and poet, who claimed to come from the planet Saturn and made music for the Space Age while dressed as an Egyptian pharaoh. Describing himself as an alien on earth, Sun Ra linked the alienation of Black people in the United States with visions of other planets, looking backward to a history of Black abduction and forward into a galactic future. As Paul Youngquist writes in A Pure Solar World: Sun Ra and the Birth of Afrofuturism,

Sun Ra crossed the inner city with outer space to create music as progressive socially as it was aesthetically. As a response to a world preoccupied with the space race and oblivious to racial injustice, Sun Ra’s music announces not merely a demand for a better world but a program for building one. (2016)

Paul Youngquist

Sun Ra crossed the inner city with outer space to create music as progressive socially as it was aesthetically. As a response to a world preoccupied with the space race and oblivious to racial injustice, Sun Ra’s music announces not merely a demand for a better world but a program for building one. (2016)

In a concert recorded in 1960, released in 2002 as Music from Tomorrow’s World, Sun Ra asks, “If we are here / Why can’t we be there?” — an Afrofuturist question if there ever was one.

Although the word Afrofuturism had not yet been uttered, Sun Ra clearly stands as a forefather of the movement. While Elizabeth C. Hamilton acknowledges how crucial Sun Ra’s mythology is to the development of Afrofuturism, she also encourages adopting a wider, and less male-centric, view of Afrofuturism’s origins. Hamilton begins her survey of Afrofuturism in visual art with Harriet Tubman, treating the historical icon as a symbol of the future and prototype of Afrofuturism. Hamilton also examines the nineteenth- and twentieth-century art of Harriet Powers and Alma Thomas as Afrofuturist “narratives of fugitivity that run parallel with their biographical realities” (2022). Hamilton “recenters the founding of Afrofuturism, placing it around black women artists and their cultural production rather than the nearly exclusively credited ‘soulful spaceman’ Sun Ra” (2022). The history and project of Afrofuturism runs deep.

The immediate heir to Sun Ra’s musical experimentation was astrofunk pioneer George Clinton. Clinton’s collective of musicians, Parliament-Funkadelic (P-Funk) sketched “a musical blueprint for a near future in which blacks turn majority and regulate their lives through the powers and possibilities of funk” (Youngquist, 2016). Youngquist describes the opening track of The Mothership Connection as “alien invasion with a difference” (2016):

We have taken control as to bring you this special show. We will return it to you as soon as you are grooving. Welcome to radio station WEFUNK, better known as we-funk, or deeper still the Mothership Connection, home of the extraterrestrial brothers, dealers of funky music, P-Funk, uncut funk, the bomb. (Parliament, 1975)

P-Funk reanimates Black life, deploying, in the words of the “Prelude” to Parliament’s Clones of Dr. Funkenstein, “specially designed afronauts capable of funkatizing galaxies” (1976).

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, Afrofuturism gained traction through the prescient works of prolific sci-fi authors like Samuel R. Delany (Trouble on Triton, Hogg) and Octavia Butler (Parable of the Sower, Bloodchild and Other Stories). Comic book creators (like Milestone Media) and visual artists (like Ellen Gallagher) also combined Black lives with technology and visions of the future.

With the naming of Afrofuturism came efforts to uncover and discuss works within this framework, and it became clear that “there was a tradition of sci-fi or futuristic works created by people of African descent that stretched back to precolonial Africa” (Womack, 2013). As Womack writes, “the world of black sci-fi geeks and comic book fans who felt isolated in their interests and ignored by mainstream sci-fi creators had a virtual home, an aesthetic to give their craft and pastime an academically based validity” (2013). The rise of the internet was essential to the growth of Afrofuturism, enabling creators to share their work and enthusiasts to find community.

Afrofutures have steadily become more visible on big screens. Womack mentions the box-office success of The Matrix (Wachowski and Wachowski, 1999), which “included a cast of multiethnic characters, the polar opposite of the legacy of homogeneous sci-fi depictions so great that even film critic Roger Ebert questioned whether The Matrix creators envisioned a future world dominated by black people” (2013). Blade (Norrington, 1998) starred Wesley Snipes as a vampire hero, and Denzel Washington played humanity's savior in the postapocalyptic The Book of Eli (Hughes and Hughes, 2010). Will Smith put a “cosmic dent in the monolithic depiction of the sci-fi hero” (Womack, 2013) in films like Independence Day (Scott, 1996), Men in Black (Sonenfeld, 1997), I Am Legend (Lawrence, 2007), and After Earth (Shyamalan, 2013). Recently, more Black creators are driving depictions of varied speculative worlds on small and silver screens — from movies like Get Out (Peele, 2017), Sorry to Bother You (Riley, 2018) and Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (Coogler, 2022) to TV series like Misha Green’s Lovecraft Country (2020) and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ adaptation of Octavia Butler’s Kindred (2022).

Even as science fiction and Afrofuturism gain more mainstream attention, the movement continues to thrive outside the constraints of major companies and corporations thanks to the Internet. In the early days of the Internet, listservs and forums did significant work in spreading the movement, allowing Afrofuturists from across the globe to “tell their stories, share their stories, and connect with audiences inexpensively — a gift from the sci-fi gods” (Womack, 2013). Now, with social media platforms and ever-developing video, art, and gaming technology, those connections are more feasible than ever. As Womack writes, “The storytelling gatekeepers vanished with the high-speed modem, and for the first time in history, people of color have a greater ability to project their own stories” (2013).

In the next section, we’ll examine two examples of Afrofuturism in contemporary popular culture: the music of Janelle Monáe and the Black Panther movies.

Examples of Afrofuturism: Janelle Monáe’s discography and Black Panther’s Wakanda

Janelle Monáe is perhaps the best known contemporary heir of Afrofuturism’s musical lineage. The pop icon’s discography narrates a sci-fi storyline, evidenced by her titles: Metropolis: The Chase Suite (2008), The ArchAndroid (2010), The Electric Lady (2013), and Dirty Computer (2018). Monáe’s artistry extends beyond her music. Her high-concept videos, liner notes, and Tumblr provide the story around the songs; Dirty Computer was released as an “emotion picture,” a 50-minute narrative film accompanying the album, and Monáe published a short story collection, The Memory Library: And Other Stories of Dirty Computer.

In her albums before Dirty Computer, Monáe took on the persona of Cindi Mayweather, an android programmed with the rare rock-star proficiency package and a working soul. In the year 2719, she lives in Metropolis, a city created as a haven after five world wars decimated the earth, now a hedonistic playground for robo-zillionaires riddled with ethnic, race, and class conflict. When Cindi falls in love with a human, forbidden in Metropolis, she becomes an outlaw and eventually realizes that she is the ArchAndroid — the prophesied cyborg messiah who will unite and liberate Metropolis. As Alyssa Favreau writes in Janelle Monáe’s The ArchAndroid, Monáe draws upon the “legacy of science fiction writers using their stories to imagine alternative futures, better futures” and creates “a world of limitless potential that assures her a place in a musical lineage begun by artists like Sun Ra and George Clinton” (Favreau, 2021). The choice to take on this persona is itself an Afrofuturist move: “By inhabiting Cindi Mayweather, Monáe is able to exist simultaneously as twenty-first-century pop royalty and as the legendary prototype android of that far future” (Favreau, 2021). Echoing the words of Sun Ra, “If we are here / Why can’t we be there?”

The cover art of The ArchAndroid evokes a classic Afrofuturist aesthetic: futuristic technology with an ancient Egyptian influence. The music video for "Tightrope" stylizes Afrofuturism differently, engaging with recent rather than ancient history. Set in an asylum in which dancing is banned for its potentially magical effects, the video’s aesthetic seems more of the twentieth than twenty-eighth century. Monáe/Cindi, rocking a pompadour and a tuxedo, leads a subversive dance party inspired by the styles of Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, James Brown, Prince, David Bowie, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe:

While Monáe’s earlier albums are set in the twenty-eighth century, Dirty Computer takes place in a near future where people deemed “dirty” are “cleansed” by having their memories forcibly wiped. As the narrative film explains, “You were dirty if you looked different. You were dirty if you refused to live the way they dictated. You were dirty if you showed any form of opposition at all” (Monáe, 2018). Through the speculative worlds surrounding her albums, Monáe explores what it means to find liberation in a hostile world. An openly pansexual, nonbinary Black artist, Monáe fuses her artistry with activism.

Dirty Computer was released in the same year as Black Panther, and Monáe was working on the album in Atlanta while Black Panther was filming nearby. Monáe says, “It just felt like a great, an amazing time for Afrofuturism. [...] For me, Afrofuturism is extremely important because we get to, as black folks in this world, we get to speak through science fiction and magical surrealism. We get to speak about our stories told from our own mouths in the future, and what happens to us” (Kakaire, 2018).

Black Panther engaged with Afrofuturist aesthetics and ideals before the word was written. When Stan Lee and Jack Kirby first introduced Wakanda in the comic books, they depicted a “man-made jungle” of technological vines, flowers, and boulders. The comics scripted by Christopher Priest and, later, Ta-Nehisi Coates incorporated some Afrofuturist ideas, but Bukatman names the Wakanda envisioned onscreen by director Ryan Coogler, production designer Hannah Beachler, and costume designer Ruth E. Carter “the most compelling and coherent vision to date of an Afrofuturist Wakanda” (2022). Through “deep consideration of the relations of past to present to future,” the creators steeped “their vision in equal measures of history and extrapolation” (Bukatman, 2022).

Black Panther begins with an alternative history. Millions of years ago, a meteorite containing vibranium — the strongest substance in the universe with extraordinary powers — crashed into Africa. Five tribes eventually settled the area around the meteorite's impact point, calling it Wakanda. The tribes were at war until the Panther goddess Bast led a warrior shaman to the heart-shaped herb, a plant granting him superhuman powers. This warrior became the first Black Panther and king of Wakanda. With the power of vibranium, Wakanda became the most technologically advanced nation in the world, but, if the world knew about Wakanda’s resources, the nation would never see peace. Instead, Wakanda exists secretly in isolation and the Black Panther protects Wakanda from outside threats. During the ceremony to induct the new Black Panther, the heart-shaped herb takes the individual to the ancestral plane, where they usually encounter previous Black Panthers and figures from their past.

The lore of Wakanda is full of Afrofuturist fusions. Ancient history is combined with futuristic technology; Shuri’s attempts to synthetically recreate the heart-shaped herb in Wakanda Forever link religious mysticism and scientific experimentation. The ancestral plane visualizes a form of “ancestor worship,” which Tricia Rose names as a part of Black culture and “countering a historical erasure” (Dery, 1994). Wakanda imagines a resistant counter history, “an African nation never conquered, never colonized, never subservient” (Bukatman, 2022). As Wakanda hides from the world, it recasts the symbolism of the “veil” metaphor Du Bois deployed to mark the separateness of Black experience. In Black Panther,

The ‘vast veil’ is no longer a tool of dehumanization, but instead is employed willfully as the secret marker of Wakanda’s immunity from definitions imposed from without. Wakanda has decided how it will be seen or unseen, just as Black Panther has decided for his Black embodied self. (Bukatman, 2022)

Wakanda reverses all sorts of stereotypes about Blackness and animality, darkness, and “primitiveness.” Through extensive research in Africa — including Lesotho, Senegal, South Africa, and Kenya — the design teams of the films create a detailed world which incorporates real traditions and aesthetics from a variety of African cultures. In Wakanda Forever, guards use precise rhythms of water-drums to lower the protective barrier around Wakanda, an exemplary Afrofuturist moment in which African culture is interwoven tightly with sci-fi tech.

The Black Panther films are not immune to criticism. The movies spawned the term “Wakandafication”: “the homogenization of African cultures into something singular and ahistorical, more palatable (too palatable, is the suggestion) to white audiences” (Bukatman, 2022). Perhaps Wakanda’s Pan-African aesthetic and uncolonized history, clearly pictured through an American gaze, is oversimplified, leading to a “flattening, rather than an honoring, of diversity, an aesthetics divorced from regional histories and traditions” (Bukatman, 2022). Not to mention the broader conversation about the commodification of Black bodies and cultures by corporations like Marvel/Disney.

Nonetheless, the Black Panther movies display the power of Afrofuturism. These superhero films populated by and focused on Black characters, especially strong Black women, combat a long history of whitewashed sci-fi.

As Bukatman writes, “It’s difficult now, if not impossible, for me to think of Janelle Monáe and not of Shuri, and vice versa: two young Astro-Black women so comfortably inhabiting a technological future-alternative that they own” (2022). Janelle Monáe and the creators of Black Panther decolonize imaginations.

The future of Afrofuturism

Our visions of the future have shifted throughout the first quarter of the twenty-first century. Afrofuturism has stretched to incorporate new technologies, locations, and disciplines. Earlier Afrofuturism focused on twentieth-century techno-culture, the digital divide, and Western tech, music, and art. Afrofuturism 2.0 — the new-and-improved mode, so to speak — was first discussed at Emory University’s 2013 Alien Bodies conference. Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E. Jones describe it in Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness:

Afrofuturism 2.0 is the early twenty-first century technogenesis of Black identity reflecting counter histories, hacking [...], database logic, cultural analytics, deep remixability, neurosciences, enhancement and augmentation, gender fluidity, posthuman possibility, the speculative sphere, with transdisciplinary applications. (2016)

Afrofuturism 2.0 aims for a Pan-African scope, accounting for regional differences and spanning the African diaspora, and it is characterized by five broad interests: metaphysics, aesthetics, theoretical and applied science, social sciences, and programmatic spaces (Anderson and Jones, 2016). Afrofuturism 2.0 embraces Astro-Blackness, “an Afrofuturistic concept in which a person’s black state of consciousness, released from the confining and crippling slave or colonial mentality, becomes aware of the multitude and varied possibilities and probabilities within the universe” (Anderson and Jones, 2016).

The liberation promised by Astro-Blackness reflects the freedoms offered by speculative fiction to Black authors — and any authors seeking to imagine a world different from the one we live in. As Womack writes, Afrofuturism’s “intrigue with sci-fi and fantasy itself inverts conventional thinking about black identity and holds the imagination supreme”:

Black identity does not have to be a negotiation with awful stereotypes, a dystopian view of the race [...], an abysmal sense of powerlessness, or a reckoning of hardened realities. Fatalism is not a synonym for blackness. (2013)

In other words, speculative fiction facilitates stories of Black flourishing that can extend beyond commenting on the techno-corporate horrors of our reality (though it does that just as well).

Womack writes, “Afrofuturist artists have an orientation toward what is to come while being constantly aware of the past. They have expansive imaginations, expanding on what is possible, not just what the world has offered in the past” (2013). Afrofuturism excavates the past and pictures alternative histories. It warns of the dystopian futures prefigured by our present while dreaming of destined liberation.

As LaFleur writes, “Afrofuturism serves as a vehicle to not only liberate Black bodies but also liberate all humans.” The (Afro)future is whatever you can imagine, so dream big.

Further Afrofuturism resources on Perlego

Hampton, G. and Parker, K. (2020) The Bloomsbury Handbook to Octavia E. Butler. Bloomsbury. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1357210/the-bloomsbury-handbook-to-octavia-e-butler-pdf.

Jackson, G., Lawson L., and Manick, C. (eds.) (2021) The Future of Black: Afrofuturism, Black Comics, and Superhero Poetry. Blaire. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3198754/the-future-of-black-afrofuturism-black-comics-and-superhero-poetry-pdf.

Steinskog, E. (2017) Afrofuturism and Black Sound Studies. Springer International Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3494513/afrofuturism-and-black-sound-studies-culture-technology-and-things-to-come-pdf.

Keeling, K. (2019) Queer Times, Black Futures. NYU Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/921319/queer-times-black-futures-pdf.

Afrofuturism FAQs

What is Afrofuturism in simple terms?

What is Afrofuturism in simple terms?

What is Astro-Blackness?

What is Astro-Blackness?

What are good examples of Afrofuturism?

What are good examples of Afrofuturism?

Bibliography

Anderson, R. and Jones, C.E. (eds.) (2016) Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness. Lexington Books.

Bukatman, S. (2022) Black Panther. University of Texas Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3832209/black-panther-pdf.

Hamilton, E. C. (2022) Charting the Afrofuturist Imaginary in African American Art: The Black Female Fantastic. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3547302/charting-the-afrofuturist-imaginary-in-african-american-art-the-black-female-fantastic-pdf.

Delany, M. R. (2017). Blake; or, The Huts of America. Harvard University Press.

Dery, M. (1994) “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose,” in Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture. Duke University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1466333/flame-wars-the-discourse-of-cyberculture-pdf.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1995) Dark Princess. University Press of Mississippi.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1920) “The Comet,” in Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil. Harcourt, Brace and Company. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15210/15210-h/15210-h.htm#Chapter_X.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2018) The Souls of Black Folk. Myers Education Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3030533/the-souls-of-black-folk-by-web-du-bois-with-a-critical-introduction-by-patricia-h-hinchey-pdf.

Favreau, A. (2021) Janelle Monáe’s The ArchAndroid. Bloomsbury. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2778075/janelle-mones-the-archandroid-pdf.

Janelle Monáe (2018) Janelle Monáe - Dirty Computer [Emotion Picture]. 27 April. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdH2Sy-BlNE.

Janelle Monáe (2010) Janelle Monáe - Tightrope [feat. Big Boi] (Video). 13 March. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwnefUaKCbc.

Jemesin, N. K. (2013) “How Long ’Til Black Future Month? The Toxins of Speculative Fiction, and the Antidote that is Janelle Monae,” NKJemisin.com, 30 September. Available at: https://nkjemisin.com/2013/09/how-long-til-black-future-month/.

LaFleur, I. (no date) “Afrofuturism,” IngridLaFleur.com. Available at: https://www.ingridlafleur.com/afrofuturism.

Monáe, J. (2018) Dirty Computer. Bad Boy Records. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/album/2PjlaxlMunGOUvcRzlTbtE?si=KxSUUqYhQemzug1tZ7hV-Q.

Monáe, J. (2008) Metropolis: The Chase Suite. Bad Boy Records. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/album/3T3bJi3cvwR5U7ihwgEwF1?si=zo4v8_k4T1mRReg20bcoHw.

Monáe, J. (2010) The ArchAndroid. Bad Boy Records. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/album/7MvSB0JTdtl1pSwZcgvYQX?si=YECDvq7cToauLtBoXo-AFA.

Monáe, J. (2013) The Electric Lady. Bad Boy Records. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/album/3bnHtSmmsgJiG82hGCmsq9?si=SGU6V1StS92UUiWvY3NWIQ.

Monáe, J. (2022) The Memory Librarian: And Other Stories of Dirty Computer. HarperCollins.

Monáe, J. (no date) “The Electric Lady.” Available at: https://57821.tumblr.com/.

Parliament (1975) The Mothership Connection. The Island Def Jam Music Group. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/album/4q1HNSka8CzuLvC8ydcsD2?si=yOyaohGNQZeOMFJfb5LZ2A.

Parliament (1976) Clones of Dr. Funkenstein. UMG Recordings. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/album/658zJVrLYgMe6bUUJhBXmJ?si=_D3W4UkYQM2EBJpQpcXieQ.

Sun Ra Arkestra (2002) Music from Tomorrow’s World. [CD]. Atavistic.

Womack, Y. (2013) Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture. Lawrence HIll Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3473784/afrofuturism-the-world-of-black-scifi-and-fantasy-culture-pdf.

Youngquist, P. (2016) A Pure Solar World: Sun Ra and the Birth of Afrofuturism. University of Texas Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3273797/a-pure-solar-world-sun-ra-and-the-birth-of-afrofuturism-pdf.

Zamalin, A. (2019) Black Utopia: The History of an Idea from Black Nationalism to Afrofuturism. Columbia University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/862383/black-utopia-the-history-of-an-idea-from-black-nationalism-to-afrofuturism-pdf.

Filmography

After Earth (2013) Directed by M. Night Shyamalan. Available at: Tubi.

Black Panther (2018) Directed by Ryan Coogler. Available at: Disney+.

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022) Directed by Ryan Coogler. Available at: Disney+.

Blade (1998) Directed by Stephen Norrington. Available at: Amazon Prime Video.

Get Out (2017) Directed by Jordan Peele. Available at: FXNOW.

I Am Legend (2007) Directed by Francis Lawrence. Available at: Amazon Prime Video.

Independence Day (1996) Directed by Roland Emmerich. Available at: Amazon Prime Video.

Men in Black (1997) Directed by Barry Sonnenfeld. Available at: Peacock.

Sorry to Bother You (2018) Directed by Boots Riley. Available at: Roku Channel.

The Book of Eli (2010) Directed by Albert Hughes and Allen Hughes. Available at: HBO Max.

MSt, Women's, Gender & Sexuality Studies (University of Oxford)

Paige Elizabeth Allen has a Master’s degree in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from the University of Oxford and a Bachelor’s degree in English from Princeton University. Her research interests include monstrosity, the Gothic tradition, illness in literature and culture, and musical theatre. Her dissertation examined sentient haunted houses through the lenses of posthumanism and queer theory.