![]()

Part 1

Fundamentals

Although this book is focused on helping you master Autodesk® Revit® Architecture software, we recognize that not everyone will know how to find every tool or have a complete understanding of the workflow. The chapters in Part 1 will help you build a foundation of essential knowledge and may even give the veteran Revit user some additional insight into the basic tools and concepts of building information modeling (BIM).

- Chapter 1: Introduction: The Basics of BIM

- Chapter 2: Principles: UI and Project Organization

- Chapter 3: The Basics of the Toolbox

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: The Basics of BIM

In this chapter, we cover principles of a successful building information modeling (BIM) approach within your office environment and summarize some of the many tactics possible using BIM in today’s design workflow. We explain the fundamental characteristics of maximizing your investment in BIM and moving beyond documentation with an information-rich model.

In this chapter, you’ll learn to:

- Understand a BIM workflow

- Leverage BIM processes

- Focus your investment in BIM

What Is Revit?

Autodesk® Revit® software is a BIM application that utilizes a parametric 3D model to generate plans, sections, elevations, perspectives, details, and schedules—all of the necessary instruments to document the design of a building. Drawings created using Revit are not a collection of 2D lines and shapes that are interpreted to represent a building; they are live views extracted from what is essentially a virtual building model. This model consists of a compilation of intelligent components that contain not only physical attributes but also functional behavior familiar in architectural design, engineering, and construction.

Elements in Revit are managed and manipulated through a hierarchy of parameters that we will discuss in greater detail throughout this book. These elements share a level of bidirectional associativity—if the elements are changed in one place within the model, those changes are visible in all the other views. If you move a door in plan, that door is moved in all of the elevations, sections, perspectives, and so on in which it is visible. In addition, all of the properties and information about each element are stored within the elements themselves, which means that most annotation is merely applied to any view and is transient in nature. When contrasted with traditional CAD tools that store element information only in the annotation, Revit gives you the opportunity to more easily extract, report, and organize your project data for collaboration with others.

Before we get started with a detailed examination of Revit, let’s take a step back and develop a better understanding of the larger concepts of building information modeling and how they will affect your practice of architecture.

Understanding a BIM Workflow

According to the National Institute of Building Sciences (

www.nibs.org), a BIM is defined as “a digital representation of physical and functional characteristics of a facility” that serves as a “shared knowledge resource for information about a facility forming a reliable basis for decisions during its life cycle from inception onward.” While this is the definition of the noun used to represent the electronic data, the verb form of building information

modeling is equally important. BIM is both a tool and a process, and one cannot realistically exist without the other. This book will help you to learn one BIM tool—Revit Architecture—but we hope that it will also teach you about the BIM process.

Building information modeling implies an increased attention to more informed design and enhanced collaboration. Simply installing an application like Revit and using it to replicate your current processes will yield limited success. In fact, it may even be more cumbersome than using traditional CAD tools.

Regardless of the design and production workflow you have established in the past, moving to BIM is going to be a change. Regardless of where you fall on the adoption curve, you’ll still need some tools to help transition from your current workflow to one using BIM tools. To begin, we’ll cover some of the core differences between a CAD-based system and a BIM-based one.

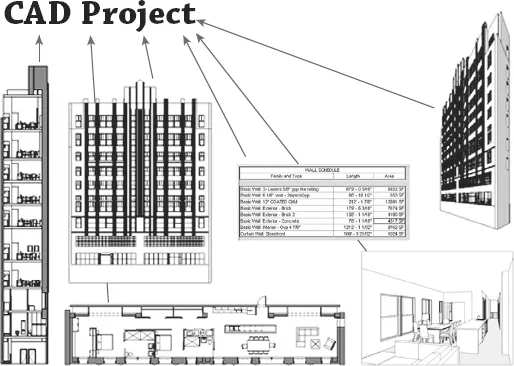

Moving to BIM is a shift in how designers and contractors approach the design and documentation process throughout the entire life cycle of the project, from concept to occupancy. In a traditional CAD-based workflow, represented in Figure 1.1, each view is drawn separately with no inherent relationship between drawings. In this type of production environment, the team creates plans, sections, elevations, schedules, and perspectives and must coordinate any changes between files manually.

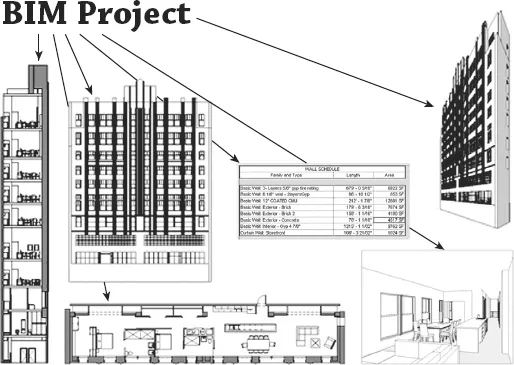

In a BIM-based workflow, the team creates a 3D, parametric model and uses this model to generate the drawings necessary for documentation. Plans, sections, elevations, schedules, and perspectives are all by-products of creating a building information model, as shown in Figure 1.2. This enhanced representation methodology not only allows for a highly coordinated documentation but also provides the basic model geometry necessary for analysis, such as daylighting studies, energy usage simulation, material takeoffs, and so on.

Leveraging BIM Processes

As architects or designers, we have accepted the challenge of changing our methodology to adapt to the nuances of documentation through modeling rather than drafting. We are now confronted with identifying the next step. Some firms look to create even better documents, whereas others are leveraging BIM in building analysis and simulation. As we continue to be successful in visualization and documentation, industry leaders are looking to push BIM to the next plateau. Many of these possibilities represent new workflows and potential changes in our culture or habits, which require you to ask a critical question: What kind of firm do you want, and how do you plan to use BIM?

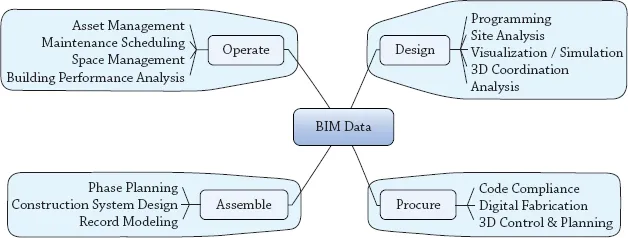

As the technology behind BIM continues to grow, so does the potential. A host of things are now possible using a building information model; in fact, that list continues to expand year after year. Figure 1.3 shows some of the potential opportunities.

We encourage you to explore ongoing research being conducted at Penn State University (http://bim.psu.edu), where students and faculty have developed a catalog of BIM uses and project execution guidelines that have been adopted into the National BIM Standard–United States, Version 2 (http://nationalbimstandard.org). Another important aspect of supporting numerous BIM uses is the development of open standards. The organization known as buildingSMART International (www.buildingsmart.com) provides a global platform for the development of such standards. Groups from a number of regional chapters around the world are generating information exchange standards that will soon have a profound impact on the ways in which we share model data with our clients and partners. Some of the latest developments include:

- IFC (Industry Foundation Classes) version 4

- COBie—Construction Operations Building Information Exchange

- SPie—Specifiers’ Properties Information Exchange

- BCF—BIM Collaboration Format

For a general overview of the approach to standardizing exchanges with information delivery manuals (IDM) and model view definitions (MVD), visit http://buildingsmart.com/standards/idm/mvd/mvd-process.

When moving to the next step with BIM—be that better documentation, sustainable analysis, or facility management—it’s important to look at your priorities through three different lenses:

- Visualize

- Analyze

- Strategize

Understanding these areas, specific...