![]()

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

Our streets and squares make up what we call the public realm, which is the physical manifestation of the common good. When you degrade the public realm, the common good suffers.

—James Howard Kunstler

THE DESIGN OF CITIES begins with the design of streets. To make a good city, you need good streets, and that means streets where people want to be. Streets need to be safe and comfortable, they need to be interesting, and they need to be beautiful. They need to be places.

We often think of buildings when we think of urban design—as we should. Great streets require great buildings. Good streets can get by with merely good buildings; great or merely good, the art of architecture is clearly indispensable. But streets are the spaces between the buildings, and those spaces need the art of placemaking. Placemaking makes the street spaces into settings where people want to be. A place is not a place until there are people in it.

We’ll look at great streets in this book and explore what made them great places. Most of them are beautiful, and so it is important to point out that the cliché about beauty being in the eye of the beholder is wrong: we all intuitively know beautiful places when we experience them. If we walk through an arcade in Venice and come out in the Piazza San Marco, no one has to tell us that this is a profound and uplifting experience. There can also be a great deal of beauty in everyday experience, as we see on many “ordinary” Main Streets in American small towns. When the buildings and trees lining the street give it a sense of enclosure, and the proportions and details form a harmonious whole, Main Street becomes a place where we want to linger, sharing a common experience with our neighbors and fellow citizens.

Tragically, we rarely build streets like that today. The overwhelming majority of the streets in America have been built since World War II, and most of them were built for cars rather than people—like the six-lane arterial road in the middle of nowhere lined with strip malls, shopping malls, big box centers, and the other detritus of modern suburban life (Figure 1.2). These cheaply built, poorly designed sites and buildings do not feel like authentic places to us: there is no there there.1 The roads are what the writer James Howard Kunstler calls “auto sewers”—suburban “thoroughfares” sized by engineers to make the traffic flow like water in a pipe. Sometimes it seems more like sludge in a sewer pipe.

Not surprisingly, the streets that result look as though they were made for cars. No one walks on them if they can possibly avoid it (Figure 1.3). The problem with these streets is not just their location, far from anything except other shopping centers and big box stores. Their design and construction are bad for people, too. The scale is vast and frightening, speeding cars roar by, there are large swales where the sidewalk should be, and crossing the street is difficult, with long expanses between traffic lights. Even when you get to your destination, you still have to cross a large parking lot that has no sidewalks or shade trees. It’s all ugly, and it’s all depressing.

Fortunately, after decades of fleeing cities and old towns, Americans have embraced walkable towns and neighborhoods again. There’s a common understanding that the automobile-based patterns of building made a physical environment inferior in many ways to the old pedestrian-based one, and that we need to remake our cities, towns, and streets for people. Accordingly, the Federal and local governments are appropriating billions of dollars in a well-intentioned—yet scattered and intermittent—effort to rebuild the nation’s roads.

Less encouraging is that many of the professionals involved in remaking our streets bring with them the criteria and biases of their specialties, and that frequently prevents them from designing streets where people want to be. Bicycle specialists, pedestrian specialists, transit specialists, and even Complete Street specialists may understand the need to add a bike lane or a streetcar, but they often don’t understand placemaking or the importance of the public realm. The professionals in charge usually continue the late-twentieth-century pattern of allocating most of the square footage there primarily to the motor vehicle and its movement—now with the movement of bicycles and buses added. They introduce innovations that make the street safer for those riding bikes or even traveling on foot, but at the same time they repeatedly diminish the space and beauty of the street for the walker. And when you diminish the public realm, you diminish the common good.

THE TRADITIONAL STREET

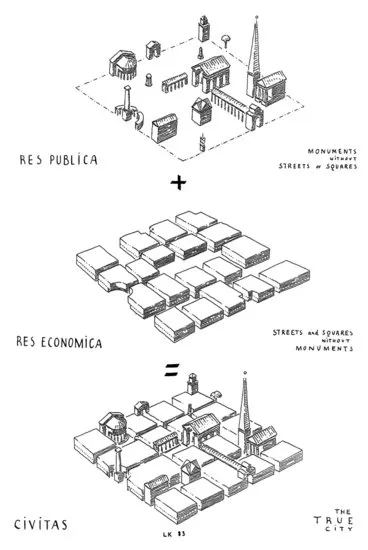

The history of urban design and street design in Western civilization has its roots in ancient Rome and Athens. For the Greeks and the Romans, the city was the place where men and women came together to make a good and civilized life. The words “civil,” “civilization,” and “citizen” come from the Roman word for city, “civitas.” From the ancient Greek word for city, “polis,” we get “polite,” “political,” and “police,” which reflect the classical idea that the city was a political body of citizens, as well as the place where they politely came together to create civilization. For centuries, the first job of the architect when designing a new building was to make or reinforce the public realm (Figure 1.5).

Ancient Romans talked about the public realm, which they called the res publica, as the place where the citizens came together in the polis. It was shaped by the buildings in the private realm (res privata). In The Architecture of Community, the architect and urban designer Léon Krier uses diagrams to show that each realm is incomplete without the other, while the two combine to make the complete city (Figure 1.6).2 In addition to open space (streets and squares and parks), the public realm also includes public buildings such as churches and town halls. Much of the art of traditional urban design and town planning consists of two things: shaping and programming the public realm into a place where pedestrians want to be, and strategically placing public buildings (such as a market or place of worship or theater) so that they are understood to be more important than the private buildings (Figure 1.4).

In the modern world, we also have the semipublic domain of stores, businesses, and places of entertainment, such as movie houses, restaurants, and nightclubs. Office buildings now frequently tower above the church steeples that used to be the tallest structures, and corporate headquarters like the Chicago Tribune Tower or the Woolworth Building in New York are distinguished from speculative office buildings by their monumentality and ornate architecture. All these buildings play a large part in making urban places where people want to be. Some of these spaces were meant to inspire a sense of grandeur; others were designed to be intimate. Most important, whether we are strolling through the ruins of the Roman Forum or exploring the streets of Back Bay, Boston, all of these environments were built to a human scale.

THE GRID

An American book about street design must mention the grid, however briefly. The rectilinear grid has been used in the planning of towns and cities since at least the fifteenth century BC, when the Chinese started a tradition of gridded plans that they still employ today. In the Western world, the use of rectilinear grids for town plans goes back to at least 2600 or 2500 BC, and the Romans institutionalized a standard gridded plan for the places colonized by the Roman Empire. Roman cities, fortified garrisons, and colonial outposts were designed around the famous cardo and decumanus. Cardi ...