![]()

PART I

Functional Anatomy of Reproduction

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Anatomy of Male Reproduction

E.S.E. HAFEZ

The male gonads, the testes, lie outside the abdomen within the scrotum, which is a purselike structure derived from the skin and fascia of the abdominal wall. Each testis lies within the vaginal process, a separate extension of the peritoneum, which passes through the abdominal wall at the inguinal canal. The deep and superficial inguinal rings are the deep and superficial openings of the inguinal canal. Blood vessels and nerves reach the testis in the spermatic cord, which lies within the vaginal process; the ductus deferens accompanies the vessels but leaves them at the orifice of the vaginal process to join the urethra. Besides permitting the passage of the vaginal process and its contents, the inguinal canal also gives passage to vessels and nerves supplying the external genitalia.

The spermatozoa leave the testis by efferent ductules that lead into the coiled duct of the epididymis, which continues as the straight ductus deferens. Accessory glands discharge their contents into the ductus deferens or into the pelvic portion of the urethra.

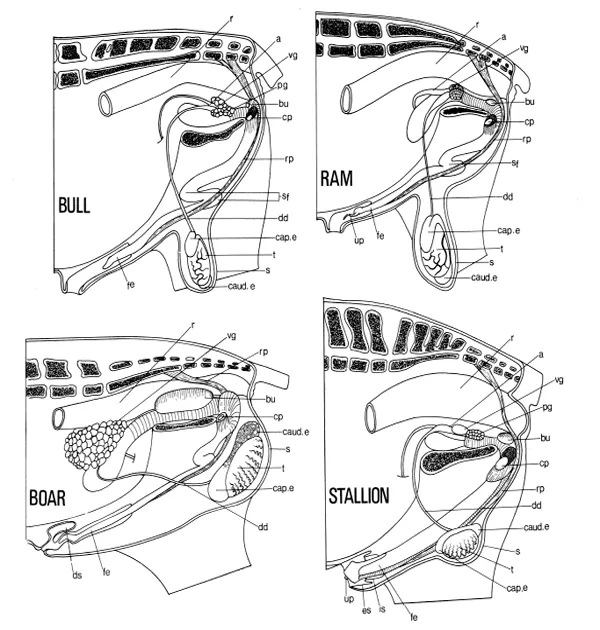

The urethra originates at the neck of the bladder. Throughout its length it is surrounded by cavernous vascular tissue. Its pelvic portion, which is enclosed by striated urethral muscle and receives secretions from various glands, leads into a second penile portion at the pelvic outlet. Here it is joined by two more cavernous bodies to make up the body of the penis, which lies beneath the skin of the body wall. A number of muscles grouped around the pelvic outlet contribute to the root of the penis. The apex or free part of the penis is covered by modified skin—the penile integument; in the resting condition it is enclosed within the prepuce. The topographic features of the organs of the important farm species are shown in Figure 1-1.

The testis and epididymis are supplied with blood from the testicular artery, which originates from the dorsal aorta near the embryonic site of the testes. The internal pudendal artery supplies the pelvic genitalia and its branches leave the pelvis at the ischial arch to supply the penis. The external pudendal artery leaves the abdominal cavity via the inguinal canal to supply the penis, scrotum, and prepuce. Lymph from the testis and epididymis passes to the lumbar aortic lymph nodes. Lymph from the accessory glands, urethra, and penis passes to the sacral and medial iliac nodes. Lymph from the scrotum, prepuce, and peripenile tissues drains to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Afferent and efferent (sympathetic) nerves accompany the testicular artery to the testis. The pelvic plexus supplies autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) fibers to the pelvic genitalia and to the smooth muscles of the penis. Sacral nerves supply motor fibers to the striated muscles of the penis and sensory fibers to the free part of the penis. Afferent fibers from the scrotum and prepuce travel mainly in the genitofemoral nerve.

DEVELOPMENT

Prenatal Development

The testes develop in the abdomen, medial to the embryonic kidney (mesonephros). The plexus of ducts within the testis becomes connected to mesonephric tubules and so to the mesonephric duct, to form the epididymis, ductus deferens, and vesicular gland. The prostate and bulbourethral glands form from the embryonic urogenital sinus and the penis forms by tubulation and elongation of a tubercle that develops at the orifice of the urogenital sinus.

Two agents produced by the fetal testis are responsible for this differentiation and development (1). Fetal androgen causes development of the male reproductive tract. “Müllerian inhibiting substance,” a glycoprotein, is responsible for suppression of the paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts from which the uterus and vagina develop (2). Abnormalities in differentiation and development of gonads and ducts can result in varying degrees of intersexuality (3).

FIGURE 1-1. Diagram of the male reproductive tracts as seen in left lateral dissections. a, Ampulla; bu, bulbourethral gland; cap. e, caput epididymidis, caud. e, cauda epididymidis; cp, left crus of penis, severed from the left ischium; dd, ductus deferens; ds, dorsal diverticulum of prepuce; es, prepenile prepuce; fe, free part of the penis; is, preputial fold; pg, prostate gland; r, rectum; rp, retractor penls muscle; s, scrotum; sf, sigmoid flexure; t, testis; up, urethral process; vg, vesicular gland. (Adapted from Popesko, Atlas der topographischen anatomie der Haustiere. Vol. 3, Jena: Fischer, 1968.)

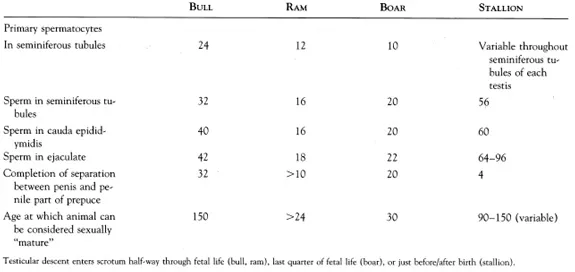

Descent of the Testis

During testicular descent (4), the gonad migrates caudally within the abdomen to the deep inguinal ring. It then traverses the abdominal wall to emerge at the superficial inguinal ring, which is, in fact, the much-enlarged foramen of the genitofemoral nerve (L3, L4). The testis completes its migration by passing fully into the scrotum. Descent is preceded by the formation of the vaginal process, a peritoneal sac extending through the abdominal wall and enclosing the inguinal ligament of the testis. The inguinal ligament of the gonad is often called the gubernaculum testis, and it terminates in the region of the scrotal rudiments. Descent follows the line of the gubernaculum testis. The time of descent varies (Table 1-1). In the horse, the epididymis commonly enters the inguinal canal before the testis, and that part of the inguinal ligament connecting testis and epididymis (proper ligament of testis) remains extensive until after birth.

TABLE 1-1. Development of the Male Reproductive Trace in Farm Animals (weeks)

Sometimes the testis fails to enter the scrotum. In this condition (cryptorchidism), the special thermal needs of testis and epididymis are not met, although the endocrine function of the testis is unimpaired. Bilaterally cryptorchid males therefore show more or less normal sexual desire but are sterile. Occasionally some of the abdominal viscera pass through the orifice of the vaginal process and enter the scrotum; scrotal hernia is particularly common in pigs.

Postnatal Development

Each component of the reproductive tracts of all farm animals grows in size relative to overall body size and undergoes histologic differentiation. Functional competence is not achieved simultaneously in all components of the reproductive system. Thus, in the bull, the capacity for erection of the penis precedes the appearance of sperm in the ejaculate by several months. In rams, the terminal segment of the epididymis is morphologically “adult” at 6 weeks, but the initial segment is not so until 18 weeks (5). At puberty all the components of the male reproductive system have reached a sufficiently advanced stage of development for the system as a whole to be functional. The period of rapid development that precedes puberty is known as the prepubertal period, although this period is itself sometimes referred to as “puberty,” During the postpubertal period, development continues and the reproductive tract reaches full sexual maturity months or even years after the age of puberty. In horses, significant increases in testicular weight, daily sperm production, and epididymal sperm reserves occur at 15 years of age. Some important anatomic changes that occur during postnatal development are summarized in Table 1-1.

TESTIS AND SCROTUM

The testis is secured to the wall of the vaginal process along the line of its epididymal attachment. The position in the scrotum and the orientation of the long axis of the testis differ with the species (Fig. 1-1). The arrangement of tubules and ducts within the testis in the bull is shown in Figure 1-2. The histologic and cytologic characteristics of the cellular components of the seminiferous tubules are summarized in Table 1-2. The rete testis is lined by a nonsecretory cuboidal epithelium.

Testicular size varies throughout the year in seasonal breeders (ram, stallion, camel). Removal of one testis results in considerable enlargement of the remaining gonad (up to 80% increase in weight), In the unilateral cryptorchid, removal of the descended testis may be followed by descent of the abdominal testis as it enlarges.

The interstitial (Leydig) cells, which lie between the seminiferous tubules, secrete male hormones into the testicular veins and lymphatic vessels. The spermatogenic cells of the tubule divide and differentiate to form spermatozoa. Just before puberty, the sustentacular (Sertoli) cells of the tubule form a barrier (6), which isolates the differentiating germ cells from the general circulation. These sustentacular cells contribute to fluid production by the tubule and may produce the Müllerian-inhibiting factor found in the rete fluid of adult males (2). The sustentacular cells do not increase in numbers after puberty is attained. This may limit spermiogenesis. Sperm production increases with age in the postpubertal period and is subject to seasonal changes in many species. Castration of prepubertal males suppresses sexual development. Regressive changes in behavior and structure take place following castration of adult males. Castration is a standard procedure in animal husbandry to modify aggressive male behavior and to eliminate undesirable carcass qualities, e.g., boar taint.

FIGURE 1-2. Schematic drawing of the tubular system of the testis and epididymis in the bull (for clarity the duct system of the rete testis is omitted). cap. e, Caput epididymidis; caud. e, cauda epididymidis; corp. e, corpus epididymidis; dd, ductus deferens; de, duct of the epididymis; ed., efferent ductule; lb, lobule with seminiferous tubules; rt, rete testis; st, straight tubule; t, testis. (Simplified from Blom and Christensen. Nord Vet Med 1968;12:453.)

Spermatogenesis disorders are monitored by changes in sperm parameters in the ejaculate or by infertility. Turner et al, (7) conducted extensive studies to identify the proteins which play major roles in spermatogenesis and are subsequently transported into the blood stream.

Autonomic innervation of the testis plays a major role in regulating the functions of the male genitourinary tract. Adrenergic, cholinergic, and nonadrenergic noncholinergic (NANC) mechanisms operate in a highly orchestrated fashion to ensure reliable storage and release of urine from the bladder to regulate the transport and storage of sperm in the reproductive tract and coordinate the emission/ejaculation of the sex accessory glands (8).

TABLE 1-2. Functional Histology of the Mammalian Testis

| SEGMENT | HISTOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS |

| Tunica albuginea | A thick, white capsule of connective tissue surrounding the testis; made primarily of interlacing series of collagenous fiber. |

| Seminiferous tubules | Appear as large isolated structures, round or oblong in outline; varying appearance due to the complex coiling of the tubules at many different angles and levels. Between the tubules are masses of interstitial (Leydig) cells, which produce the male sex hormones. |

| Spermatogonia | Lie in the outermost region of the tubule; round nuclei appear as an irregular layer within surrounding connective tissue. Nuclei are small size and dark stain due to presence of large numbers of chromatin granules. |

| Primary spermatocytes | Located just inside an irregular layer of spermatogonia and Sertoli cells... |