- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The shift towards being as environmentally-friendly as possible has resulted in the need for this important volume on the topic of biocatalysis. Edited by the father and pioneer of Green Chemistry, Professor Paul Anastas, and by the renowned chemist, Professor Robert Crabtree, this volume covers many different aspects, from industrial applications to the latest research straight from the laboratory. It explains the fundamentals and makes use of everyday examples to elucidate this vitally important field. An essential collection for anyone wishing to gain an understanding of the world of green chemistry, as well as for chemists, environmental agencies and chemical engineers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Green Catalysis, Volume 3 by Paul T. Anastas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Catalysis with Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases

Vlada B. Urlacher

1.1 Properties of Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases

1.1.1 General Aspects

Biocatalytic oxyfunctionalization of non-activated hydrocarbons is considered as ‘potentially the most useful of all biotransformations’ [1]. Since biooxidation-based applications using cytochrome P450 monooxygenases often yield compounds that are difficult to synthesize using traditional synthetic chemistry, they have attracted considerable attention from chemists, biochemists and biotechnologists. Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s or CYPs) are heme-containing monooxygenases, which were recognized and defined as a distinct class of hemoproteins about 50 years ago [2, 3]. These enzymes got their name from their unusual properties to form reduced (ferrous) iron–carbon monoxide complexes in which the heme absorption Soret band shifts from 420 to ~450 nm [4, 5]. Essential for this spectral characteristic is the axial coordination of the heme iron by a cysteine thiolate, which is common to all P450 monooxygenases [6, 7]. The phylogenetically conserved cysteinate is the proximal ligand to the heme iron, with the distal ligand generally assumed to be a weakly bound water molecule [8].

In terms of nomenclature, the root symbol CYP, denoting cytochrome P450, is followed by an Arabic number representing the particular families (generally groups of proteins with more than 40% amino acid sequence identity), a letter for the respective subfamilies (greater than 55% identity) and a number determining the specific gene; for example, CYP102A1, which represents the cytochrome P450 BM-3 from Bacillus megaterium. An exception is the CYP51 family, where sterol Δ22-desaturases are grouped together based on their identical function and not on sequence similarity [9].

Since their discovery, the P450s have been studied in enormous detail due to their involvement in a plethora of crucial cellular roles – from carbon source assimilation, through biosynthesis of hormones to carcinogenesis, drug activation and degradation of xenobiotics.

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases build one of the largest gene families, with currently more than 7700 gene sequences found in all domains of life [10]. Despite less than 20% sequence identity across the gene superfamily, P450 enzymes appear to take on a similar structural fold [11] (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The crystal structure of the P450 BM-3 monooxygenase domain with palmitoleic acid bound adapted from pdb 1SMJ: heme and palmitoleic acid in black.

The number of P450 monooxygenases identified is constantly increasing due to microbial screenings and the rapid development of DNA sequencing techniques, leading to an increasing number of sequenced genomes. Functional characterization of new members of the P450 gene family thus offers a route to diverse building blocks, closely linked with the retrieval of new important compounds.

1.1.2 Chemistry of Substrate Oxidation by P450 Monooxygenases

Most P450 enzymes catalyze the reductive scission of dioxygen, while bound to the heme iron:

The process requires the consecutive delivery of two electrons in the form of hydride ions to the heme iron. P450 monooxygenases are external monooxygenases that utilize reducing equivalents (electrons in the form of hydride ions), ultimately derived from the pyridine cofactors NADH or NADPH and transferred to the heme via redox partners [12, 13].

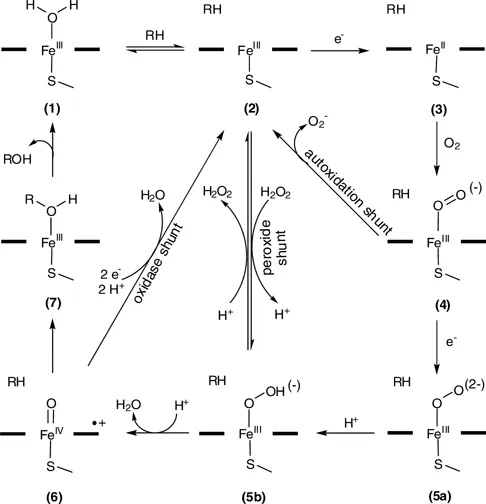

The classical P450 catalytic cycle as recently revised by Sligar and colleagues [14] is depicted in Scheme 1.1. Substrate binding in the active site induces the dissociation of a water molecule that is bound relatively weakly as the sixth coordinating ligand to the heme iron to the thiolate 1. This, in turn, induces a shift of the heme iron spin state from low-spin (S = 1/2) to high-spin (S = 5/2) and a positive shift in heme iron reduction potential in the order of 130–140 mV [15]. The increased potential the delivery of the first electron, which reduces the heme iron from the ferric form, Fe(III) (2), to the ferrous form, Fe(II) (3). After the first electron transfer, the Fe(II) (3) binds dioxygen, resulting in a ferrous dioxygen complex (4). The timely delivery of the second electron converts this species into a ferric peroxy anion (5a). Subsequent steps in the P450 cycle are considered to be relatively fast with respect to the electron transfer. The ferric peroxy species 5a is protonated to a ferric hydroperoxy complex (5b) (compound 0) and then further protonated to a high-valent ferryl–oxo complex (6) (compound I), accompanied by the release of a water molecule through heterolytic scission of the dioxygen bond in the preceding intermediate (7). Compound I is considered to be the intermediate catalyzing the majority of P450 reactions; however, compound 0 may also be important for some P450-dependent catalytic reactions [16], for example in the epoxidation of C=C double bonds [17].

Scheme 1.1 Catalytic cycle of P450 monooxygenases.

Under certain circumstances, P450 monooxygenases can enter one of three abortive cycles, also referred to as uncoupling pathways (Scheme 1.1). If the second electron is not delivered to reduce the short-lived ferrous–oxy complex 4, it can decay, forming superoxide (autoxidation shunt). The inappropriate positioning of the substrate in the active site is often the molecular reason for the two other uncoupling cycles. The ferric hydroperoxy intermediate 5b can collapse and release hydrogen peroxide (peroxide shunt), whereas decay of 6 (compound I) is accompanied by the release of water (oxidase shunt). The intracellularly formed peroxide and superoxide might damage P450 monooxygenases through heme macrocycle degradation and apoprotein oxidation [18, 19]. For industrial applications, it is particularly important to note that the uncoupling pathways in all cases consu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the Editors

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1: Catalysis with Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases

- Chapter 2: Biocatalytic Hydrolysis of Nitriles

- Chapter 3: Biocatalytic Processes Using Ionic Liquids and Supercritical Carbon Dioxide

- Chapter 4: Thiamine-Based Enzymes for Biotransformations

- Chapter 5: Baeyer–Villiger Monooxygenases in Organic Synthesis

- Chapter 6: Bioreduction by Microorganisms

- Chapter 7: Biotransformations and the Pharma Industry

- Chapter 8: Hydrogenases and Alternative Energy Strategies

- Chapter 9: PAH Bioremediation by Microbial Communities and Enzymatic Activities

- Index

- End User License Agreement