Obsidian Aquisition as Evidence for Seafaring

The Aegean

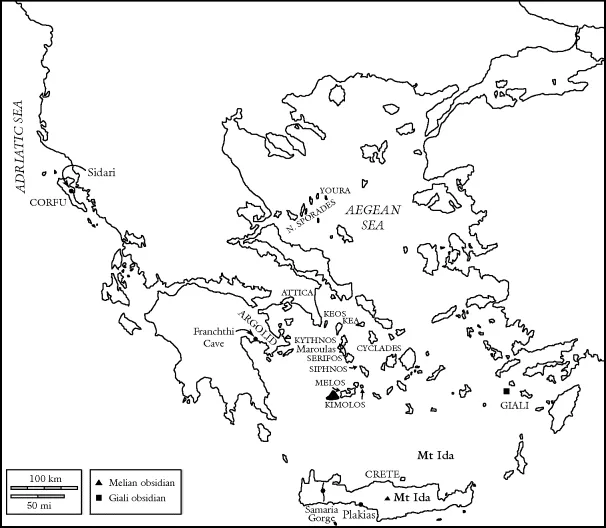

While seafaring is attested in the Pacific with the arrival of human beings in Australia some 40,000 years ago (O'Connell and Allen 2004),1 the earliest evidence of Mediterranean seafaring dates to the tenth to ninth millennium BC: obsidian found in Mesolithic levels in the Franchthi Cave in the Greek Peloponnese (Broodbank 2006).2 Analysis has identified with great precision the source of obsidian as the Cycladic island of Melos (Tykot 1996; Tykot and Ammerman 1997). Since Melos had never been attached to the mainland during the Holocene, the obsidian must have been brought by sea.

According to Perlès, a specialist on the Franchthi Cave and obsidian, the quantities found are too small – at most 1 percent of the total lithic material – to have been the result of regular maritime expeditions to Melos by the occupants of the cave, and she suggests occasional collection or very sporadic acquisition through exchange routes (1990a: 30; 2003a: 81). Later, in the Upper Mesolithic, the amounts of obsidian increased thirtyfold, but they were still quite small: obsidian made up only 3.15 percent of the total lithic material (Perlès 1990a: 48). At that time, the material was imported in unworked blocks and worked on the site.

According to Perlès, the acquisition, working, and distribution of Meli obsidian carried out by individual users who traveled to acquire their own supplies, or came upon it as a side benefit during fishing trips. Rather, she argues it was collected and distributed by specialists (Perlès 1990b; 1992). Her reasoning is that obtaining the obsidian would have required a long trip by both land and water, expert knowledge of the location of the source and of the best route there, access to a boat, expertise in navigation, and time away from other tasks to undertake the long trip. This would have precluded all but a few determined venturers. She suggests, therefore, that the bearers of obsidian to Franchthi were specialized seafaring groups who pre-formed the obsidian into cores on Melos for transport. Because great skill was required in knapping, and this was unlikely to have been a skill acquired by a householder for his own production – one man could produce far more blades than a single household, or even a small village, required – Perlès suggested that the obsidian gatherers also acted as itinerant “middlemen,” moving from village to village, knapping the obsidian as required. The amounts found at Franchthi seem to preclude any great activity on the part of the inhabitants of the Franchthi Cave in this “industry” of acquisition, transport, and production.

The missing element in this picture – people who do seem to have been involved in the acquisition, transport, and distribution of obsidian – may be provided by the recently excavated Mesolithic island site of Maroulas on Kythnos, whose occupation is contemporary with the Franchthi Cave (Sampson 1998; Sampson et al. 2002). Obsidian from Melos has been found at Maroulas in large quantities, amounting to 16.87 percent of the total lithic assemblage (as compared with 3.15 percent at Franchthi). Cores were found, indicating that obsidian was worked on the site, although, according to the excavators, the large proportion of obsidian tools (36.36 percent) may mean that some were imported as finished products (Sampson et al. 2002). The occurrence of obsidian at Maroulas adds substantially to the evidence of Franchthi Cave for Aegean seafaring in the Mesolithic, and it also suggests a possible explanation for the small amounts of obsidian found at Franchthi: that site lay near the end of an obsidian transport route that ultimately led to the Argolid: Melos, Kimolos, Siphnos, Seriphos, Kythnos, Keos, Attica, Argolid.

Maroulas is also the only Aegean island site to have provided evidence of occupation in the Mesolithic in the form of dwelling remains and burials (Sampson et al. 2002). Three circular flagstone floors more than 3 meters in diameter and bordered with small and large stones have been found, as well as three flagstone constructions in irregular ellipsoid form that have not been so well preserved. Under the surface of one of the circular floors, an adult burial was discovered under a large slab. Another burial was that of a child interred with the bone of a dog. In all, nine burials were found, most were only partly preserved; other burials appear to have been destroyed by sea erosion. The burial customs (inhumation under the floors of houses, and burials associated with dogs), and the use of circular dwellings, have parallels in the Natufian culture of Syria and Palestine, dated 12,500–10,200 BP,3 and are thus in the same time frame as the early finds of obsidian at Franchthi Cave (Davis and Valla 1978; Valla 1998: 187; Davis 1991). People, presumably families, were living on Maroulas for at least part of the year, although they may have incorporated their stays into a seasonal travel pattern in order to maximize their resources.

How did these earlier obsidian carriers cross the sea? For this date, there are no preserved remains of boats in this area, and reed vessels seem to be the likeliest possibility. To test this, in 1988, a group of archaeologists and students used a reproduction of a double-prowed papyrus vessel propelled by oars on a test voyage from Laurion in mainland Greece to Melos (Tzala 1995), a route perhaps similar to that taken by the carriers of the Franchthi obsidian, had they gone part of the way overland. The modern trip involved a full-time crew of six, with an additional rower occasionally used, and required seven days (not counting delays caused by adverse weather). Reed boats were in use in Corfu in the 1960s (Sordinas 1970: 31–4 and plates 1, 2), and papyrus or reed boats are still used in Sardinia at the regatta festival of fishermen held annually in August (“Is Fassonis”) at Santa Giusta, in the vicinity of Monte Arci, the principal Sardinian obsidian source.

Another Aegean island site that has yielded Melian obsidian in Mesolithic levels as evidence of maritime visits is the Cyclops Cave on Youra, one of a group of islands (the “Deserted Islands” – Kyra Panagia, Youra, Psathoura) in the Northern Sporades (Sampson 1998; Broodbank 2000: 116; Sampson, Kozlowski, and Kaczanowska 2003). Other small Mesolithic sites have been found in the island group, and Sampson (1998: 20) reports three submarine cavities that are likely sites and await investigation.

Fifteen obsidian artifacts, including seven microlith tools, were found in the upper levels of the Cyclops Cave, but the absence of obsidian cores suggests that the tools were brought to the site ready to use. Identical obsidian microlith forms are known from the Antalya region of Anatolia and from the Öküzını Cave on the Cilician coast (Sampson et al. 1998; Sampson, Kozlowski, and Kaczanowska 2003: 128), as well as at Belbidi, and Pinarbasi in central Anatolia. Although no direct connections can be traced between the Aegean cave and Anatolia, it is probable that the people from Mesolithic sites on the Aegean islands had contacts with western Anatolia, to which the Northern Sporades from a natural island bridge (van Andel and Shackleton 1982; van Andel 1990; Cherry 1990: 192–4). The fact that some artifacts from the cave were made from local siliceous rocks suggests that the island also had links with the Mesolithic of mainland Greece. It may even have been connected to the mainland, or been within very close “stepping stone” range of it, within human history (see Map 1.1) (Cherry 1990: 165–7).

The evidence thus suggests not only considerable seafaring but also the existence of a “complex network of trade activities and large-scale movements in the Aegean and the Greek mainland, extending to Anatolia and indirectly even to the Levant, in the ninth millennium BC” (Sampson 1998: 20–1; see also Renfrew and Aspinall 1990). This is in keeping with the Mesolithic lifestyle, which was generally one of seasonal migrations in search of a variety of resources, with the same campsites being visited repeatedly in an annual cycle. In fact, Broodbank (2000: 115) suggests that part of the Mesolithic population of the islands spent periods of the year moving around the Aegean, likening them to those who “colonised the sea” in early Melanesia (Gosden and Pavlides 1994). In such a situation, sites are difficult to recognize archaeologically: they are “spots on the landscape to which people return regularly,” within the context of continual movement within the larger maritime area, and such “occupants” are unlikely to leave many traces behind them (Gosden and Pavlides 1994: 169). Yet the occupants did leave behind traces of a network of exchange focused on obsidian, which included other worked stone and stone-working methods, and surely other, ephemeral materials. Perhaps most important, it would have served as a network of information.

Central Mediterranean Obsidian Sources and Routes

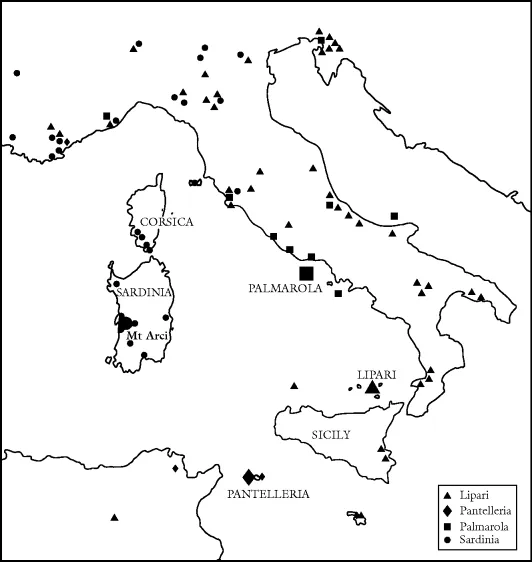

While Melos was the main source of obsidian in the Aegean,4 other important sources of obsidian existed in the central Mediterranean. Perhaps the best known of these sources was Lipari, one of the Aeolian islands. At about the same time that people from the Franchthi Cave first acquired obsidian from Melos, people seeking obsidian visited (but did not settle) the Aeolian Islands, especially Lipari, perhaps attracted by the fiery displays of its volcano (Leighton 1999: 28, 33–4, 72–3). Obsidian would have been easily collected, and there is evidence that reduction into pre-cores occurred on the island long before any settlement took place (Leighton 1999, 75). In the Tyrrhenian Sea, the earliest evidence currently comes from Capri, where from the Middle Neolithic (end of fifth and early fourth millennium) finds of Lipari obsidian have been made in the Grotta delle Felci, the local sanctuary. These are especially significant since they suggest that early exchange may have taken the form, not so much of “trade,” as of “dedications” by visitors to holy sites.

Some prospectors at Lipari surely came from nearby Sicily, which was not a true island and had been continuously inhabited since the Palaeolithic.5 The earliest exported Lipari obsidian there was discovered in a Mesolithic context (Aranguren and Revedin 1996: 35) and is thought to have been the result of exploration and possibly sporadic exchange rather than systematic exploitation.

At the end of the fifth millennium settlement on the Aeolian islands began when people from Sicily established themselves at Castellaro Vecchio on Lipari and subsequently at Contrada Rinicedda on Salina (Cavalier and Bernabo Brea 1993–4: 987–8; Castagnino Berlinghieri 2003: 45; 51, 121). Both these sites have provided strong evidence for the working of obsidian, which suggests that it was the motivation for their establishment. The large numbers of flakes found in all the Aeolian settlements, from the most ancient (Castellaro Vecchio) up to the final Eneolithic, assure that the local population directly controlled the operations of extracting and working the obsidian (Nicoletti 1997: 260). Obsidian from Lipara was carried regularly to the Italian coast by sea, where the Calabrian Acconia project has demonstrated its reduction and distribution to a number of settlements of the Middle and Late Neolithic (Ammerman 1985; Malone 2003: 283). Obsidian from Lipari also reached southern France, perhaps by way of Corsica, and from there it was carried to central and northern Italy and Croatia (Robb and Farr 2005: 36). The data from Lipari suggest that the height of obsidian extraction and working occurred toward the end of the Neolithic (the period called the Diana facies), with a subsequent progressive decline in the Chalcolithic and total disappearance at the beginning of the Bronze Age.

In the central Mediterranean, in addition to the Aeolian islands, Sardinia and the small islands of Pantelleria and Palmarola (one of the Pontine Islands) were sources of obsidian, and they show similar patterns of late settlement (Tykot 1996). The largest and most heavily exploited of these sources was Monte Arci in Sardinia. The obsidian from that site was of the highest quality, and it was widely distributed to Corsica, central and northern Italy, and southern France (Tykot 1996: 61; Walter 2000: 145). It was probably the presence of obsidian that attracted settlers to the island in the sixth millennium. The sources of obsidian found at the small islands of Palmarola and Pantelleria were less heavily utilized. The obsidian from Palmarola is not of high quality, but the island was easily accessible from the mainland, and obsidian could be picked up on the beach; some was found on the Tyrrhenian coast of Italy at the site of La Marmotta (Walter 2000: 143). To the south, the island of Pantelleria, which lies 200 kilometers southwest of Sicily, played a subordinate and localized role in the distribution of obsidian by the middle of the sixth millennium, with material from the island being carried to the tiny neighboring island of Lampedusa, and to Sicily, Malta (150 km distant), and Tunisia (113 km distant) (Camps 1986: 40, 41, 44; Trump 1963; Nicoletti 1997; Vargo, Tykot, and Tosi 2003).6

Anatolian Sources Of Obsidian

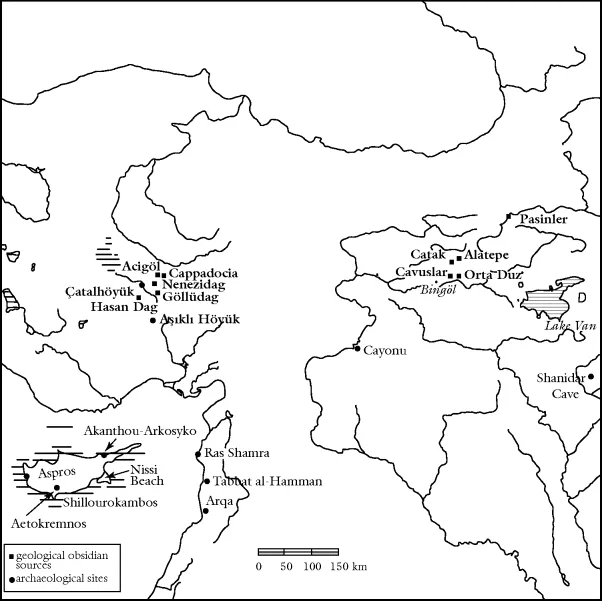

Another major source of obsidian lay inland in Anatolia, where it occurs principally in two volcanic areas: in the Lake Van region in eastern Anatolia, and in Cappadocia in south central Anatolia (Renfrew, Dixon, and Cann 1966: 35). The travels of Anatolian obsidian also provide important evidence for trade networks and cultural contacts, although these were mostly by land.

In the Upper Palaeolithic small amounts of Anatolian obsidian traveled substantial distances – from Van some 400 kilometers to Shanidar Cave in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains of Kurdestan in Iraq, and from Cappadocia some 350 kilometers to Antalya on the southwest Anatolian coast. In the Mesolithic Anatolian obsidian continued to travel, providing information about potential routes. Small amounts reached as far south as Jericho in the eighth millennium BC(a period called the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA)).

By the seventh millennium the pace of obsidian transport had stepped up dramatically. Large amounts were found at the Turkish site of Çatal Hüyük (6300–5500 BC) (Renfrew, Dixon, and Cann 1966), where the excavators suggest its working was a specialization. The craftsmen themselves probably fetched the material from the source (approximately 200 km distant), or sent others, who then can be called traders, “in the strict sense that they were specialists in the transport and exchange of materials for gain” (Renfrew, Dixon, and Cann 1966: 52)

These travels of obsidian in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic East occurred within, and did much to create, a cultural interaction...