eBook - ePub

Geographies of British Modernity

Space and Society in the Twentieth Century

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geographies of British Modernity

Space and Society in the Twentieth Century

About this book

This volume brings together leading scholars in the geography and history of twentieth-century Britain to illustrate the contribution that geographical thinking can make to understanding modern Britain.

- The first collection to explore the contribution that geographical thinking can make to our understanding of modern Britain.

- Contains thirteen essays by leading scholars in the geography and history of twentieth-century Britain.

- Focuses on how and why geographies of Britain have formed and changed over the past century.

- Combines economic, political, social and cultural geographies.

- Demonstrates the vitality of work in this field and its relevance to everyday life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geographies of British Modernity by David Gilbert, David Matless, Brian Short, David Gilbert,David Matless,Brian Short in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Historical Geographies of British Modernity

Geographies of Modernity

In 1902 Heinemann of London published Halford Mackinder’s Britain and the British Seas, a work of geographical synthesis in which ‘the phenomena of topographical distribution relating to many classes of fact have been treated, but from a single standpoint and on a uniform method’ (1902: vii). Reread a century later, Mackinder’s account of Britain contains some elements that seem archaic and others that still appear perceptive or even visionary. One diagram in the book shows ‘the relative nigresence of the British population’ (1902: 182). This used an index based on samples of hair colour to map the patterning of what were described as long-skulled and dark Celts, long-skulled and blond Teutons, and remnant groups of ‘round-headed men’. Mackinder’s diagram is now used only as a pedagogic device to illustrate the contemporary obsession with racial difference (and the shaky evidence on which it was based). Students familiar with the cultural complexities of early twenty-first-century Britain find the language, aims and methods of Mackinder’s treatment of ‘racial geography’ perplexing, amusing, risible or offensive. In contrast, Mackinder’s comments on the potential of tidal power as a replacement for fossil fuels, seem like a prophecy still waiting to be fulfilled:

A vaster supply of energy than can be had from the coal of the whole world is to be found in the rise and fall of the tide upon the submerged plateau which is the foundation of Britain. No one has yet devised a satisfactory method of harnessing the tides, but the electrical conveyance of power has removed one at least of the impediments, and sooner or later, when the necessity is upon us, a way may be found of converting their rhythmical pulsation into electrical energy. (1902: 339)

It is appropriate to open this book on the Geographies of British Modernity, the first volume dedicated specifically to the historical geography of twentieth-century Britain, with reference to Mackinder, not just because Britain and the British Seas provides a convenient starting point from the early years of the century. As we argue later in this introductory essay, it is important to think about how the discipline of geography has changed and developed over the twentieth century as a way of writing about Britain and Britishness, and Mackinder is often credited with the establishment of British academic geography. But it is also appropriate to start with Mackinder because, as Gearóid Ó Tuathail (1992) has argued, his work as both academic geographer and as politician must be interpreted as a comment on the nature of the modern world and Britain’s place within it. Mackinder is now best remembered as a geopolitician, through his theory of the ‘world heartland’ that influenced and legitimized American Cold War strategy. This work on the ‘closed heart-land of Euro-Asia’ as the ‘geographical pivot of history’ needs to be set within what was a much broader response to dramatic transformations that were taking place at the beginning of the twentieth century (Mackinder 1904: 434). Mackinder’s work can be seen as an attempt ‘to modernize traditional conservative myths about an organic community in an age where a multiplicity of international and domestic material transformations were eroding the economic foundations of the British Empire and the social world of the aristocratic establishment who ran it’ (Ó Tuathail 1992: 102). Seen from this perspective, Mackinder’s broader undertaking becomes a particular interpretation and projection of the geography of British modernity at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The term modernity is one for which there is certainly no simple or agreed definition: ‘Its periodisations, geographies, characteristics and promise all remain elusive’ (Ogborn 1998: 2). In general terms modernity has been seen as a description both of major social and material changes – particularly the emergence of the modern state, industrial capitalism, new forms of science and technology, and time-space compression – and of the growing consciousness of the novelty of these changes. This consciousness has been marked by pronounced double-sidedness or ambivalence. To be modern, in Marshall Berman’s words, ‘is to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world – and at the same time threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are’ (1983: 15). Berman’s account in All That Is Solid Melts Into Air is perhaps the most influential late twentieth century interpretation of modernity. In a key passage he outlines the different dimensions of the ‘creative destruction’ of modernity:

The maelstrom of modern life has been fed from many sources: great discoveries in the physical sciences, changing our images of the universe and our production which transforms scientific knowledge into technology, creates new human environments and destroys old ones, speeds up the whole tempo of life, generates new forms of corporate power and class struggle; immense demographic upheavals, severing millions of people from their ancestral habitats, hurtling them halfway across the world into new lives; rapid and often cataclysmic urban growth; systems of mass-communication, dynamic in their development, enveloping and binding together the most diverse people and societies; increasingly powerful nation states, bureaucratically structured and operated, constantly striving to expand their powers; mass social movements of people, and peoples, challenging their political and economic rulers, striving to gain some control over their lives; finally, bearing and driving all these people and institutions along an everexpanding drastically fluctuating capitalist world market. (1983: 16)

As Berman acknowledges, this describes a vast history which is highly differentiated in time and space. The conservative imperialism of Mackinder and many of his contemporaries in the British establishment can be seen as a reaction both to the general characteristics of these changes at the beginning of the twentieth century, and to their specific impact upon Britain and the British empire. The beginning of the twentieth century was, as Stephen Kern (1983) has suggested, a time of sweeping change in technology and culture altering understandings of time, space and the nature of the world order. Significant technological innovations of the period included the telephone, wireless telegraphy, cinema, bicycle, automobile, and airplane, while contemporary cultural and intellectual developments included the emergence of psychoanalysis, cubism and relativity. The early twentieth century witnessed an acceleration in the rate of the ‘internationalization of human affairs’, a consequence in part of the time-space compression facilitated by new technology (Ó Tuathail 1992: 103). It also saw growing pressure in Western societies from groups previously marginalized – particularly the working classes and women – for greater political power and social justice.

We return to Mackinder and questions of British modernity below, but recent work has begun to ask specifically geographical questions about the nature of modernity per se. Historical geographers such as Ogborn (1998), Pred and Watts (1992) and Gregory (1994) have begun to demonstrate the impossibility of understanding modernity (or indeed any other historical formation) in an aspatial fashion, whether the concern is for the geographical project of empire, the spatial organization of industrial production, the relations of city and country, or the symbolic geographies of modern or anti-modern nationhood (see also Graham and Nash 2000). What we wish to emphasize in this collection is the spatial fabric of the modern in all the above senses, rather than geography being simply a fixed spatial background over which historical processes play. The understanding of modern times cannot achieve sufficiency apart from the understanding of modern spaces. In Spaces of Modernity, his account of ‘London’s Geographies 1680–1780’, Miles Ogborn highlights three ways in which a geographical understanding may transform our sense of modernity: ‘through investigating the forms in which the spatial is written into theories of modernity; by acknowledging the ways in which there are different modernities in different places; and by conceptualising modernity as a matter of the hybrid relationships and connections between places’ (Ogborn 1998: 17). While this book is concerned with a very different period within ‘modernity’, these questions remain central, whether one is considering the rationalization of modern spaces through industrial policies or planning theories, the specifically British inflections of wider global processes, or ways in which local processes in twentieth-century Britain cannot be understood apart from imperial or postcolonial relationships.

If the geographies of modernity have been subject to various readings on different scales at different times, the geographies of British modernity have been less subjected to systematic analysis. Historians of twentieth-century Britain, and of the modernities of earlier British life, have developed sophisticated and often contrasting analyses of the ways in which Britain played a key role in the emergence of modernity per se, the particular inflections of the modern found in Britain as distinct from other Western powers, and the ways in which Britishness was imagined in relation to the modern (for example Colley 1992; Nava and O’Shea 1996; Schwarz 1996; Samuel 1998). This volume complements recent historical collections such as Daunton and Reiger’s Meanings of Modernity (2001), addressing Britain from the late Victorian era to 1939, and Conekin, Mort and Waters’ Moments of Modernity (1999), concerned with the period 1945 to 1964. The essays in this volume approach the geographies of British modernity through a variety of spatio-temporal themes: longitudinal analyses of social and political change, studies of national identity, archaeologies of particular sites, and discussions of the nature and scale of geographical knowledge. The temporal coverage of individual essays varies: some focus on specific moments in the century, others provide overarching surveys. Here we offer some broad introductory outlines of the geographies of the British modern.

British Modern: Something Done?

British reactions to twentieth-century modernity have been extremely variable. In recent decades a number of commentators have diagnosed a form of British disease – in essence a set of negative responses to the modern world. For example, Martin Wiener (1981) influentially argued that the idealization of the past, and particularly of an aristocratic, deferential, and British culture and had hamstrung economic flexibility and progress in the twentieth century. Such ‘declinist’ concerns are themselves not new (Friedberg 1988) – indeed one can detect a variant of this theme in the work of Mackinder, whose reaction to early twentieth-century transformations was decidedly anxious and pessimistic. Mackinder’s work illustrates the ways in which geographical scholarship has always been a part of wider cultural commentary on the world, a theme to which we return below. In the 1880s, the reaction of the British establishment to modern transformations in space and time had often taken the form of enjoinders to ever greater national effort and enlargement of Britain’s global role. J. R. Seeley’s 1883 essay on The Expansion of England can be read in just this way, not only as a statement of Britain’s manifest destiny and its global civilizing mission, but also as a necessary response to the challenges posed by modernity. Similarly, James Froude in his Oceania or England and her Colonies of 1886 stressed the need for an ever-extending role in the world:

The oak tree in the park 7or forest whose branches are left to it will stand for a thousand years; let the branches be lopped away or torn from it by the wind, it rots at the heart and becomes a pollard interesting only from the comparison of what it once was with what fate or violence has made it. So it is with nations.…A mere manufacturing England, standing stripped and bare in the world’s market-place, and caring only to make wares for the world to buy, is already in the pollard state; the glory of it is gone for ever. (1886: 387)

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the response to change had often become distinctly more pessimistic. Mackinder’s view of Britain as an ‘organic community in decay’ in the face of the forces of early twentieth century modernity was part of a developing tradition that highlighted relative decline – regarding Britain as, in Aaron Freidberg’s term, the ‘weary titan’ (Ó Tuathail 1992: 109; Freidberg 1988). Mackinder, in work from the early 1900s through to the 1940s, provided a conservative geographical analysis that sought to counter a loss of leadership and community with schemes for the maintenance of imperial order through a form of spatial organization that stressed the significance of national, regional and local scale in economic and cultural life. Geographical knowledge was itself a key component of this life:

It is essential that the ruling citizens of the world wide Empire should be able to visualise distant geographical conditions . . . Our aim must be to make our whole people think Imperially – think that is to say in spaces that that are worldwide – and to this end our geographical teaching should be directed. (1907: 37 quoted in Ó Tuathail 1992: 114)

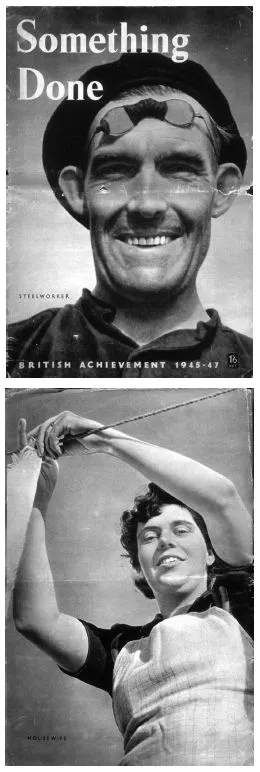

While Mackinder offered an anxious and sometimes pessimistic analysis of decline, such a passage also indicates a proponent of what Alison Light has called, in a very different context, ‘conservative modernity’, characterizing a particular kind of British reaction to substantial social and cultural change: ‘Janus-faced it could simultaneously look backwards and forwards; it could accommodate the past in the new forms of the present; it was a deferral of modernity and yet it also demanded a different sort of conservatism from that which had gone before’ (1991: 10). We can begin to draw out these concerns via a later specific document of self-consciously British modernity, the 1947 Central Office of Information publication Something Done: British Achievement 1945–47. If Mackinder’s work gives an academic geographical understanding of Britain, here we find another rendering of Britain’s modern space, which is in its own way a geographical account. A heroic steelworker stares from the front cover, a heroic housewife hangs washing on the back (figure 1.1). The publication celebrates achievement in the name of the people during and, despite austerity, carrying wartime rhetoric and publication style into peace. Inside the front cover, over a backdrop of firework celebrations on the Thames in London, Lionel Birch’s text begins:

We came out of the war victorious. We also came out of it much poorer, and needing a rest. There was no rest. There was work to do.

There were houses and power-stations to build, coal to dig, cloth to weave, ships to launch, fields to till, our trade to rebuild. There were social reforms to make – reforms we all agreed, during the war, that we must have.

So we came away from the battlefields of the world only to find new and different battles to fight. This book tells the story of some of the first victories. Here are reflected, as in a mirror, certain highlights of achievement – some things we have done as a people, things in which each one of us may take a true national pride.

In this mirror, and behind these achievements, we see also ourselves – a free people, on the move, in its ancient home. (COI 1947: 2)

The publication begins with a pronatalist celebration of the upturn in the birthrate, linked to ‘the problem of maintaining Britain’s industrial and cultural potency in a world which is very much on the look-out for any symptoms of British senility’ (1947: 6). The back-cover housewife is to produce babies as well as homes (Riley 1981). Industrial and cultural potency are backed up by accounts of power stations, development areas, television, coal, education, new towns, hydro-electric power, aviation, underground railways, films, agriculture, exports, housing, mapping, shipping and the land speed record. Such a publication connects to a wide range of planning and reconstruction literature, and anticipates guides to the Festival of Britain pavilions four years later (Banham and Hillier 1976; Matless 1998). What is striking in this context is the acutely geographical vision of achievement produced. This is in part a matter of demonstrating the physical products of reconstruction, but the new Britain being conjured in these pages in many ways resembles a geographical textbook, with aerial photographs of south Wales industrial estates, Hebburn shipyards, housing estates, London docks, new towns, and airfields turned to arable land. Regional development and global air routes are mapped, while diagrams show HEP stations and tractor production. The spirit of the Ordnance Survey, celebrated for ‘making Britain the best-mapped country in the world’ (COI 1947: 54), and itself taken as a sign of modern advancement, pervades the document as a whole. Geographical order – modern spaces well laid out, appreciated from the air, integrated into a modern regional organization – is offered as the facilitator and outcome of British achievement. And mapping itself denotes modern life, the account of the Ordnance Survey beginning: ‘During the war millions of people in Britain learned for the first time how to orient themselves, and how to find a rendezvous from a map’ (1947: 54). Changes in war and peace demand that up-to-date maps are maintained:

Figure 1.1. Steelworker and Housewife. Front and back cover of Something Done: British Achievement 1945-47

a map is a representation of the ground; and the ground, in this case, is Britain. It is a spacious ground and a varied one, and, since it is not given to any man to go all over the ground before he dies, the next best thing is for him to make an understanding study of the Post-War Ordnance Survey – and to take his choice of Britain. (1947: 55)

Mapping could not only underpin progress but cultivate citizenship (Weight and Beach 1998).

The geography of Something Done reflects a fairly conventional mid-twentieth-century sense of a modern planned economy and society, expressing a landscape which it was hoped would further a post-war social democratic consensus of stable and harmonious class relations, advancing the cause of labour through reform rather than revolution. The status of women might also advance without overturning traditional domestic gender relations. Such visions were of course highly contested, but this official document plays down any controversy. Throughout the document material production, modernized through expert knowledge, carries symbolic weight; power generation, new homes, modern mining, ships and steel. This very solid modern geography shaped official senses of midtwentieth-century Britain and Britishness, just as stories of imperial and globally commercial geographies shaped early twentieth-century accounts (Driver 2001). Different, but no less geographical, stories of a ‘late modern’ or ‘post-modern’ economy and society structure accounts of late twentiethcentury British modernity. The electronic service economy carries its own symbolic geographies, even in its more extreme rhetorics of footloose life and global interconnection. Declarations that space has been overcome are no less geographical than statements of the value of local rootedness. Zygmunt Bauman has recently described the late twentieth century as an era of ‘liquid’ or ‘fluid’ modernity, in contrast with earlier times, characterized by modernity in its ‘heavy, bulky, or immobile and rooted solid phase’ (Bauman 2000: 57). If, however, the language used to interpret this transformation is explicitly geographical, in such broad analyses there is often neglect of specific national, regional and local ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Chapter One: Historical Geographies of British Modernity

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Afterword: Emblematic Landscapes of the British Modern

- Index