- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Doing Cultural Geography

About this book

Doing Cultural Geography is an introduction to cultural geography that integrates theoretical discussion with applied examples. The emphasis throughout is on doing. Recognising that many undergraduates have difficulty with both theory and methods courses, the text demystifies the ?theory? informing cultural geography and encourages students to engage directly with theory in practice. It emphasises what can be done with humanist, Marxist, post-structuralist, feminist, and post-colonial theory, demonstrating that this is the best way to prompt students to engage with the otherwise daunting theoretical literature.

Twenty short chapters are grouped into five sections on Theory, Topic Selection, Methodology, Interpretation and Presentation. The main text is intercut with questions, suggestions for activities and short sample extracts from scholarly texts, chosen to exemplify the subject of the chapter and to stimulate further reading. Chapters conclude with glossaries and suggestions for further reading.

Doing Cultural Geography will facilitate project work from small, classroom-based activities to the planning stages of undergraduate research projects. It will be essential reading for students in modules in cultural geography and foundation courses in human geography and theory and methods.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

As people have become increasingly aware of the radical changes inherent in late modern society, there has been a growing desire to find new ways of thinking in order to reach new modes of understanding. The oil crisis of 1973 and the ensuing new wave of neo-liberal ‘globalization’ caused fundamental changes world-wide. These changes were not just in the economic and political order, but permeated into the recesses of ordinary people’s lives. Not only in the universities, but also in the media and in private encounters, virtually everyone, everywhere became increasingly conscious of the problem of creating meaning in situations in which so many of the parameters of economic, political and social life had shifted.

It is now taken for granted that the implications of a globally integrated system of production and consumption involve everyone, everywhere: industrial workers, peasant farmers, landless labourers, retired people, traders, professionals, students, people bringing up children and those trying to find work. Men and women contemplated and tried to make sense of such things as insecure employment, changed levels and modes of consumption, the obsolescence of hard won knowledge, the sidelining of old moral certainties. They speculated about whether these things were the cause or the outcome of changed relationships and power structures. They worried about changing families and sexual relationships, new expectations regarding gender and age, different ways of managing power and authority, unaccustomed notions of justice, liability, accountability and entitlement, the decline in religious observance in some places and virulent new forms of anti-secularism in others.

It was in this climate of general consciousness of the problem of finding meaning and value that the so-called ‘cultural turn’ occurred amongst intellectuals in all of the social sciences, and not only in the West. Indeed, there came to be some unease about the use of the term ‘science’ when studying society. By the ‘cultural turn’, it was implied that the accumulations of ways of seeing, means of communicating, constructions of value, senses of identity should be taken as important in their own right, rather than just a by-product of economic formations. (It still remains to be seen whether this new orthodoxy is correct.) Suddenly ‘culture’ became intellectually fashionable as a starting point for interpretation, whereas it had hitherto been seen as lacking in rigour.

Geography was no exception to this and gradually, through the 1980s, all of the sub-disciplines of human geography came to be conscious of the ‘cultural’ dimensions of their field of study: economic geographers ‘discovered’ embeddedness of local economies in local social practices; political geographers became aware of new nationalisms and notions of identity in boundary formation and exclusion; urban geographers turned their attention to lifestyle and they became enthusiastic about cultural regeneration of cities; the countryside was rethought as a cultural construction, as was nature itself; retail geographers became enthusiastic about sites of consumption, as opposed to patterns of distribution. Difference and differentiation shifted to centre stage, and yet no one was very clear about what ‘culture’ might be. In 1988 the Social Geography Study Group of the Institute of British Geographers launched its ‘cultural initiative’ and simultaneously changed its name to the Social and Cultural Geography Study Group. The following year Peter Jackson’s (1989) Maps of Meaning irrevocably changed the way in which geographers looked at issues of identity. The sub-discipline has taken off from here in its many different guises.

The change in title [of the Social Geography Study Group to include Cultural Geography] is an entirely welcome event for someone like myself who has always believed that human geography should celebrate the cultural diversity of our world and pay attention to the ways in which human beliefs, values and ideals continuously shape its landscapes. It is a change which signals a profound and, in some respects, an overdue change in geographical philosophy and methodology.

(Cosgrove 1988, quoted in Philo 1991 p. 1)

Trevor Barnes’ (1996) Logics of Dislocation is a stimulating study of the ways in which academic work cannot justifiably claim to rise above the values and modes of communication of the people who produce it. He demonstrates the significance of metaphor in economic geography, probably the branch of human geography which has been the most assiduous in attempting to avoid cultural ‘bias’ by adopting the supposedly universal, and therefore culture-free, language of mathematics. Barnes argues that the language of economic geography is as cultural as any other and just as subject to deconstruction. It is a book one could hardly have conceived of before the ‘cultural turn’.

One of the most influential texts in American cultural geography defines culture quite unambiguously as ‘a total way of life held in common by a group of people’ (Jordan and Rountree 1982 p. 4). That might seem straightforward enough but, when one thinks about it, it is meaningless. Which of us shares every aspect of our life with even one other person, let alone a group, presumably a group large enough to constitute a society? What is meant by ‘a total way of life’? Does it mean that everyone has to act and think the same way, or does it mean that some, unspecified, degree of (recognized) difference is permitted? How does ‘a way of life held in common’ cope with change: does everyone have to change in the same way at the same time? Sperber suggests that we should see culture as a ‘polythetic term’ (1996 p. 17), meaning a condition in which there is ‘a set of features such that none of them is necessary, but any large enough subset of them is sufficient for something to fall under the term’ (he simplifies a little by suggesting one thinks of this as a ‘family resemblance’). The very idea of culture as the possession of bounded groups of people is divisive and dangerous as it underpins unnecessary oppositions and enmities.

Although I have been identified with cultural geography for more than a decade, I do not believe (and never have believed) that there is any such thing as culture. Like Don Mitchell (1995; 2000) I have insisted (Shurmer-Smith and Hannam 1994) that culture is practised, not owned. It is what people do, not what they have, and they keep doing different things in different ways, with different other people all of the time. Wendy James puts it concisely when she maintains that we should think of culture as being ‘adverbial’ rather than ‘nominal’ (1996 p. 106). Culture, then, is the communicating, sense-making, sharing, evaluating, wondering, reinforcing, experimenting qualifier of what people do. Richards likens it to music, in which the performance is everything, where ‘manifestly, the purpose . . . is not to arrive at the end’ (1996 p. 126); but, for me, it is like music only if we are willing to include solo improvisation and particularly ‘jamming’, playing in creative dialogue with others, who understand what one is doing, recognize the underlying theme, but are still constantly surprised. I prefer this metaphor to the one which underlies Sperber’s view that ‘Culture is made up, first and foremost, of contagious ideas’ (1996 p. 1), which leads him to think in terms of an epidemiology.

Cultural geography, then, becomes the field of study which concentrates upon the ways in which space, place and the environment participate in an unfolding dialogue of meaning. This includes thinking about how geographical phenomena are shaped, worked and apportioned according to ideology; how they are used when people form and express their relationships and ideas, including their sense of who they are. It also includes the ways in which place, space and environment are perceived and represented, how they are depicted in the arts, folklore and media and how these artistic uses feed back into the practical. People often think of ‘culture’ and ‘tradition’ as being synonymous, but they are not; much of culture is new and conscious of its newness (and much of tradition only pretends to be old, but that is another matter). Along with many other students of ‘culture’, I am convinced that power is always involved in human constructions, communications and representations, and that one cannot, practically or conceptually, separate the cultural from the political. Different ways of behaving and making sense not only clash and compete but also contribute to the formation of each other in that conflict.

Terry Eagleton, a leading cultural theorist, concludes his most recent book by saying that ‘culture has assumed a new political importance. But it has grown, at the same time, immodest and overweening. It is time, while acknowledging its significance, to put it back in its place’ (2000 p. 131). I suggested in 1994 (Shurmer-Smith and Hannam) that the excitement with culture might rapidly evaporate, and Don Mitchell (1999) bravely announced the demise of cultural geography shortly before the publication of his excellent (2000) contribution to the field. It is not that any of us has a death wish; it is much more that those of us who believe that culture is lived, not owned, need constantly to fight against those who reify (even deify) it.

This book will strive to put culture in its place (and space, and environment). The aim is to demystify culture, maintaining that it has nothing to do with muses or eternal spirits, though one might concede space to Lorca’s duende, that passionate force which is generated when an artist is in full flow (Lorca 1975). Instead it intends to show that what matters is the performance of ordinary material beings, in their relationships with each other and with the world about them. Sometimes this performance is deliberately mystified or made artificially exclusive; at other times it can be mundane, or even vulgar and offensive. Although culture is not some essential and external force, this does not imply that it is either insubstantial or unimportant, for without the ability to conceptualize and communicate we would be less than human. As a risky corollary to this, I would assert that the more people we can conceptualize alongside and communicate with, the greater our humanity. This does not imply that everyone has to become the same. Whilst the view of ‘culture’ as the possession or identifier of groups imposes barriers between people, a concept of culture as performance allows a movement towards innovative communication, a sort of global ‘jamming’.

LEARNING VERSUS TEACHING

Given the performative view of culture I have expressed, it would be contradictory for this book to attempt to pin down a body of received wisdom relating to theory and practice in cultural geography. It would be even more inappropriate if it were to work its way round the world describing different ‘cultures’. The intention is to encourage people to do cultural geography. Doing includes looking, feeling, thinking, playing, talking, writing, photographing, drawing, assembling, collecting, recording and filming as well as the more familiar reading and listening. There is no reason automatically to associate ‘doing’ with conducting research, although far too many academics think of that as the pre-eminent activity. Doing means being active, avoiding being done to (passive), so any reading and listening must be critical and part of a dialogue. If the book is successful, learning will have taken place, but it is to be hoped that every reader will have learned different things because all the contributors have been asked to curtail the desire to teach in the sense of dictating knowledge. Learning is active, being taught is passive and, just as passive bodies atrophy, so do passive minds.

The way of practising in an academic field which customarily receives the most attention is research, which is rather strange, since the majority of undergraduate students have no desire to spend their working lives in academia. This book certainly does not pretend to be yet another manual of research methods, but it does recognize that an understanding of some of the processes involved in research helps one to read academic texts in a more engaged and critical fashion. In just the same way, an awareness of theoretical debates helps one to see the point of studies which might otherwise seem arcane. Knowing how research is undertaken helps one understand how the artefacts (books, papers, lectures etc.) are crafted. Even cultural geography generates its own cultural forms, complete with mystifications and exclusions; doing it is the way to break down the defences between teachers and taught.

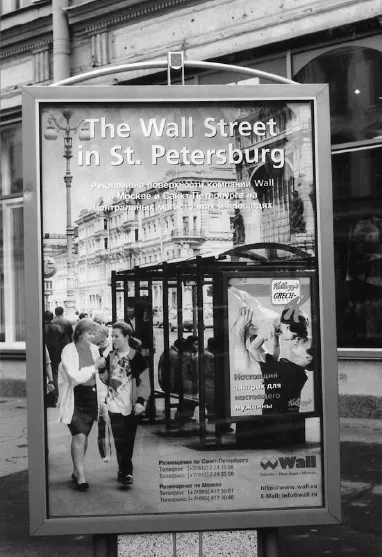

All of the authors believe that cultural geography (or any other subject) can be pursued actively at a number of different scales, from a few moments contemplating the meaning of the spatial elements in an advertisement to a lengthy research based monograph. We certainly do not think that cultural geography should be confined to the classroom or library; the doing should permeate life outside, but then should be brought back to enrich the academic endeavour. One can do cultural geography by being conscious of the range of geographical meanings and communications within ordinary activities, the manipulation of places and dispositions of people in spaces that only seem like second nature. There is spatial politics in aggressively pushing or politely standing back in a shop; in considerately making oneself as small as possible or comfortably spreading one’s legs in tourist class aeroplane seats; in covering one’s windows in voile or displaying one’s life to the world. These sorts of things may be entirely individually motivated, but I’m inclined to look for meanings and social patterns.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK

This book is structured into three distinct parts, but themes will be carried through from one part to another. Although we have designed the book with a sequential logic in mind, we do not really expect most readers to start at the beginning and keep going until the end (and then stop). The logic we have used is that of a typical programme of research, starting by thinking about theory and ending up worrying about presentation. However, as has already been said, we do not assume that all of our readers are undertaking a large research project and much of what we say is addressed to people who are doing cultural geography in different ways and at different levels.

Most chapters are written by a single author and, though we often agree with each other, we are not clones. Our different takes on cultural geography demonstrate our underlying assumption about cultural activity, namely that, even when people are in close communication, purposes and meanings never absolutely converge. We have different estimations of the value of various theoretical positions, rate different authors, favour different research methods and have different ways of presenting our thoughts. But we do all subscribe to the same common endeavour and I think we all believe that if one isn’t constantly vigilant, one can wind up being dragooned into some very unacceptable positions. We all believe that consciousness about value and meaning is important. None of the chapters purports to do more than start to break into the various areas of cultural geography and its associated methods. We have written assuming that our readers are just starting out on this sort of work and we have not attempted to compete with works addressed to people with more experience. We have placed our emphasis on brevity and this clearly means that subtlety has to go. We expect that readers will find some of our statements oversimplified – but the point was to encourage people to react and be encouraged to read the specialist literature.

The first part tackles the question of ‘theory’. It maintains that too many professional theoreticians have had a vested interest in making theory seem difficult and have constructed it as the restricted domain of the most erudite. In truth, theory is present every time someone says, ‘in my opinion . . .’. It is, however, quite important not only that one becomes conscious about one’s own theoretical position, but also that one can spot where an author is coming from – and, unfortunately, this can entail some rather hard work. There is no way in which we can do justice to all the useful cultural theory in a few pages and we are resistant to trying to give potted summaries which oversimplify. The theoretical part intends to help our readers to decide where they need to read further, depending upon their own perspectives.

The second part begins by thinking about the selection of specific areas of study through which one can do cultural geography. We stress that the discovery of process is more important than the topic itself: almost anything can be used as the gateway into systems of meaning and value. Few things are inherently trivial if one is using them to gain access to cultural processes, even though journalists like to pick on and trivialize what they know their readers will consider not to be proper ‘academic’ subjects (such as clubbing, footballers as icons, food fashions). We do, however, warn that it is important to select topics which are of an appropriate scale for the project one is attempting, whether one is preparing for a class discussion or a final year thesis.

This part continues by marrying methods with theoretical position, topic and scale of project. It is important to remember that methodology means the theory of method; it is the way in wh...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- 1 Introduction

- PART ONE THEORY INTO PRACTICE

- PART TWO DOING IT

- PART THREE MAKING SENSE

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Doing Cultural Geography by Pamela Shurmer-Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.