- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Mapping: A Critical Introduction to Cartography and GIS is an introduction to the critical issues surrounding mapping and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) across a wide range of disciplines for the non-specialist reader.

- Examines the key influences Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and cartography have on the study of geography and other related disciplines

- Represents the first in-depth summary of the "new cartography" that has appeared since the early 1990s

- Provides an explanation of what this new critical cartography is, why it is important, and how it is relevant to a broad, interdisciplinary set of readers

- Presents theoretical discussion supplemented with real-world case studies

- Brings together both a technical understanding of GIS and mapping as well as sensitivity to the importance of theory

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mapping by Jeremy W. Crampton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Naturwissenschaften & Geographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Maps – A Perverse Sense of the Unseemly

This book is an introduction to critical cartography and GIS. As such, it is neither a textbook nor a software manual. My purpose is to discuss various aspects of mapping theory and practice, from critical social theory to some of the most interesting new mapping practices such as map hacking and the geospatial web. It is an appreciation of a more critical cartography and GIS.

Why is such a book needed? We can begin with silence. If you open any of today’s prominent textbooks on cultural, political, or social geography it is more than likely that you will find little or no discussion of mapping, cartography, or GIS. A recent and well-received book on political geography for example (Jones et al. 2004) makes no mention of maps in any form, although it is subtitled “space, place and politics.” Similarly, Don Mitchell’s influential book on cultural geography and the precursor to the series in which this book appears (Mitchell 2000) deals at length with landscape, representation, racial and national geographies, but is completely and utterly devoid of the role of mapping in these important issues (and this despite Mitchell’s call for a “new” cultural geography that does not separate culture from politics!). And while a book on Key Concepts in Geography (Holloway et al. 2003) can state that “geographers have . . . studied the ways in which maps have been produced and used not only as objects of imperial power but also of postcolonial resistance” (Holloway et al. 2003: 79) the subject is then quietly dropped. Yet is it the fault of these authors – accomplished scholars – that maps and mappings are not considered part of larger geographical enquiry?

For there is a second silence. Cartographers and GIS practitioners themselves have had very little to say about politics, power, discourse, postcolonial resistance, and the other topics that fascinate large swaths of geography and the social sciences. Open any cartography or GIS textbook and you will find only deep silence about these matters. There are few cartographic voices examining the effects of GIS and mapping in the pursuit of homeland security. There are no journals of cultural or political cartography. What percentage of GIS applications are being created to address poverty? Is there feminist mapping? And if GIS and mapping have always coexisted alongside military and corporate applications then how many GIS practitioners have critically analyzed these relationships? Perhaps most arresting is the increasing separation of GIS and mapping from geography as a whole. In other words the evolution of GIScience as a technology-based subject rather than a geographic methodology (for example the focus in GIScience on formal “ontologies”). In sum, one might be forced to conclude that mapping is either incapable of such concerns, or that it rejects them.

This book is an introduction to these questions, and in part an answer to them from a critical perspective. It is an attempt to push back against the common perception that cartography and GIS are not concerned with geographical issues such as those listed above. The basic viewpoint is that mapping (i.e., cartography and GIS) is both capable of engaging with critical issues, and has often done so. While the word “critical” may be overused and ironically is itself in danger of being used uncritically (Blomley 2006), I believe its application to mapping remains fruitful and exciting. And rather than some trendy new term, there is a long and remarkable critical tradition in cartography and GIS, if in a “minor” and subjugated way. If it did not appear full-blown on the scene in the late 1980s (as the story usually goes, see Chapter 4) the critical traditions in cartography (often accessible through a historical genealogy) demonstrate how mapping and the wider field of geographical enquiry worked together for many years.

If you look back at the history of mapping it might appear that to be a “cartographer” meant to be a mapmaker, someone whose profession it was to draw maps (the word “cartography” is of early nineteenth-century origin, but “map” has a much longer history, see Krogt [2006]). It was only in the twentieth century that one could be a cartographer who studied maps but didn’t necessarily make them (or have any skill in making them) – that is, with the development of the discipline of cartography as a field of knowledge and enquiry. In this sense the discipline of cartography started to become divorced from its practice in the sense of map production. This might seem rather unusual. After all, there are no geographers doing geography and then a bunch of people in academia who study them and how they work! To be a geographer (or a physicist or chemist) is to do geography, physics, or chemistry.

But this initial distinction between mapmaking and cartography as discipline is quite hard to maintain. Although “mapmaking” in the traditional sense – as Christopher Columbus might have practiced it for example – with all of its pens, paper sheets, sextants, watermarks, and mastery of hand-drawn projections obviously has very little role in academic study today, you will nevertheless still find yourself doing mapping. Except you might call it GIS, geomatics, surveying, real-estate planning, city planning, geostatistics, political geography, geovisualization, climatology, archaeology, history, map mashups, and even on occasion biology and psychology. And in geography too we could probably agree that there are a bunch of people “doing” human geography who are distinguishable (sometimes) from the academics studying them. Just think of all those articles on the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) or on which journals geographers publish in. And finally there are the objects of critique, the (im)material products and processes of mapping and GIS. All three of these; objects, do-ers or performers of mapping, and the production of critique have complex interrelationships.

The point then is not that long ago there was something called mapmaking (which is now called geospatial technology or GIS) but rather that the understanding of what people thought they were doing with things they called maps has changed over time, as well as over space.

One of the stories that I was taught as a student is that cartography became scientific only recently, say after World War II. It did so, the story went, largely for two reasons. First, it finally threw off art and subjectivity (here reference was often made to the work of Arthur Robinson and his call for formal procedures of map design). Thus science was posed in opposition to art. Second, it became as it were “post-political” by throwing off the fatal attraction to propaganda and ideological mapping evidenced prior to and during the war, and promoting a kind of Swiss-like neutrality about politics. In doing so it paralleled the path taken by the discipline of political geography, which also found itself tarnished by its cooption during the war. But where political geography went into decline until the 1970s (Brian Berry famously called it a “moribund backwater” [R. Johnston 2001]), cartography tried to insulate itself from politics altogether by gathering around itself the trappings of objective science. The map does exactly what it says on the tin.

Yet both of these developments are myths. As the critical work of writers such as Matthew Sparke, Denis Cosgrove, and Anne Godlewska has shown, mapping as a discipline and as a practice failed to establish a rigid separation from art, nor did it ever become post-political. Chapters 5 and 12 document these myths in more detail and show what the critical response has been.

In a recent provocative article Denis Wood issued a heartfelt cry that “cartography is dead (thank God!)” (D. Wood 2003). By this he meant that the gatekeepers, academic cartographers, dwelling as it were like a parasite on actual mapping, were dying off. Maps themselves, meanwhile, have never been healthier – if only disciplinary academics would leave them be! While I have some sympathies for this position (who wants gatekeepers except other gatekeepers?) I’m not quite sure it’s correct. Rather, first because the study of mapping continues as never before, GIS is something like a $10 billion a year corporate-military business, and the advent of map hacking and map mashups has released the inner cartographer in millions of ordinary people. And second, I’m not sure it’s possible to separate mapping practice from mapping discourses quite so neatly (that minor critical tradition again!). In fact practices and discourses are intimately intertwined.

Not that discourses or knowledge go uncontested. If it was when cartography became formalized as a discipline that mapping was valorized as “scientific,” then by the 1990s a number of geographers, cartographers, and GIS practitioners drew on the larger intellectual landscape to renew a critical spirit. Today we are still drawing on that renewed linkage between mapping and geography. The central rationale of this book therefore is to demonstrate the relevance of spatial knowledge production in GIS and cartography as critical for geographers, anthropologists, sociologists, historians, philosophers, and environmental scientists.

Yet it is also plain to see that mapping has undergone a tremendous re-evaluation over the last 15 years (or longer). In accounts of this period (Schuurman 2000; Sheppard 2005), the story is told of how the encounters between mapping and its critics began with mutual suspicion and ended up with something like mutual respect. Sheppard further argues that what began with investigations of the mutual influences between GIS and society has become a “critical” GIS (with “GIS and society” representing the past and critical GIS representing the future). By this he means not just a questioning approach, but one that is critical in the sense used in the wider fields of geography and critical theory. This sense includes Marxist, feminist, and post-structural approaches among others. For Sheppard critique is a “relentless reflexivity” which problematizes various power relationships.

This narrative can itself be problematized by showing that beneath the official histories of GIS and mapping lie a whole series of “counter-conducts.” These dissenting voices, sometimes speaking past one another, sometimes speaking out from below, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2. There is therefore a minor as well as a major history of mapping and GIS, a series of “subjugated knowledges” (Foucault 2003b) that while they have popped up from time to time in the past are now making themselves felt as never before. In particular I think it is fruitful to see the history of critical GIS and cartography not as something that has only recently occurred, but one that in fact can be seen at other more distant times as well. This is what Foucault means by subjugated knowledges; ones that for whatever reason did not rise to the top, or were disqualified (for example, for not being scientific enough). But it doesn’t mean they weren’t there. Furthermore, Foucault suggests that it is the reappearance of these local knowledges alongside the official grand narratives that actually allows critique to take place. This is also an idea that we shall examine in the next chapter.

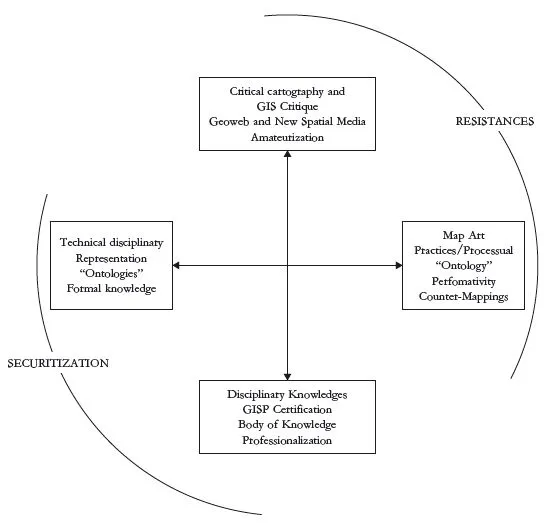

This book then appears at a transitional moment in the history of GIS and mapping. Great changes are occurring and it would be wrong to say we know exactly where they are leading. The following diagram summarizes some of these tensions which are fluctuating throughout mapping. This diagram is meant to be indicative rather than complete. Imagine that the space transected by the tensional vectors is a rubber sheet being stretched out (readers with multi-dimensional imaginations could also see it as an expanding sphere). As the sheet is stretched the field gets larger – but also thinner, perhaps dangerously so in some places (Figure 1.1).

This figure illustrates how mapping is a field of power/knowledge relations being simultaneously taken in different directions. On one axis, critical approaches, with their “one–two punch” of theoretical critique (Kitchin and Dodge 2007) and the emergence of the geoweb are questioning expert-based mapping. The increasing use of mapping technologies among so-called amateurs or novices (for example the 350–400 million downloads of Google Earth) is reshaping all sorts of new spatial media, and is allowing the pursuit of alternative knowledges. Meanwhile, on another axis, there are very real trends toward nailing knowledge down into a coherent “body” that can be mastered by experts. We’ll know they are experts because they hold a certification. What we’re talking about here then is a clerisy or set of experts.

Figure 1.1 The field of tension in mapping.

The desire for mapping to be post-political is exemplified in the diagram by those who focus on the technical issues in isolation from their larger socio-political context. Many cartography and GIS journals have now become almost completely dominated by technical issues, research which no doubt reflects the research agendas pursued by the next generation of PhDs – of which you may be one.

These different directions can be broadly described as a trend toward “securitization” of knowledge in the one direction and “resistances” in the other. Securitization of information refers to the efforts that are made to anchor, control, and discipline geographical knowledges. Another example is the increasing interest among GIScientists in “ontologies” defined as formal, abstract, and computer-tractable definitions of real-world entities and their properties. Certainly it is nothing new to observe that there is a danger whenever technology is involved of taking up mapping only as a technology. As the German philosopher Martin Heidegger remarked six decades ago “the essence of technology is by no means anything technical” (Heidegger 1977: 4). But because it is often ignored, the implications of this seemingly counterintuitive claim are taken up in various ways throughout the book.

The Need for Critique

Why is critique needed? “Critical” approaches to both GIS and cartography play important roles, but are not yet mainstream. It’s possible you might feel both that maps are terribly old-fashioned (something you studied in lower school) and yet tremendously exciting (Google Earth and homemade mapping applications, geovisualization, or perhaps human geosurveillance). Where does the truth lie?

Some of these mixed feelings were the topic of discussion in a recent issue of Area, one of the UK’s better known geography journals. Here’s Joe Painter awkwardly confessing that he’s in love:

I love maps. There, I’ve said it. I am coming out as a cartophile. Although I became fascinated by maps when I was a child (and even once told a school careers advisor that I wanted to work for the Ordnance Survey – Britain’s national mapping agency), maps have figured little in my work as an academic geographer. I suspect that many human geographers who learned their trade in the postpositivist 1980s, as I did, shared my mild embarrassment about maps. (Painter 2006: 345)

So Painter may be in love, but it’s a love that dare not speak its name: maps figure little in his work. Painter’s “cartographic anxiety” (Gregory 1994; Painter 2008) resonates with many people interested in maps and mappings. As the geographer-phenomenologist John Pickles has written, there’s a perverse sense of the unseemly about maps (Pickles 2006). These wretched unreconstructed things seem to work so unreasonably well! This sense of mapping as unseemly and unwelcome is often assumed as a given by a surprisingly large segment of people. We’re ambivalent. In the eyes of critical geographers the success of maps has not come without a price. Haven’t maps after all provided the mechanism through which colonial projects have been enabled (Akerman 2009; Edney 1997)? Isn’t there a long history of racist mapping (Winlow 2006)? Today, isn’t it simply the case that GIS and GPS are essential elements of war (N. Smith 1992)? Wasn’t Arthur “dean of modern cartography” Robinson an instrumental part of the Office of Strategic Services – the precursor to the CIA? At the very least, GIS is surely a Trojan horse (Sheppard 2005) for a return to positivism (Pickles 1991)?

These observations are valid. And yet, the same points could be made with reference to geography (or other disciplines such as anthropology) as a whole. Weren’t they involved in colonialist projects? Doesn’t the past of geography, anthropology, or biology contain racist writing and racist people? Sure.

Item: Madison Grant, who wrote the racist book The Passing of the Great Race (guess which race he feared was passing away), was a longstanding Council Member of the American Geographical Society (AGS) including during the time when Isaiah Bowman was Director, and agitated for quota-based laws in the 1920; he also published a version of the book in the AGS journal Geographical Review during wartime (Grant 1916).

Item: former President of the Association of American Geographers, Robert DeCourcy Ward, professor of geography at Harvard University, wrote a series of frankly racist eugenicist papers bitterly complaining about the low quality of immigrants into this country (Ward 1922a; 1922b). To influence anti-immigration laws he founded the “Immigration Restriction League” which succeeded in getting a literacy test into the Immigration Act of 1917.

Rather than drawing a veil over these facts, or saying that mapping is essentially a racist or capitalist tool, any honest intellectual history will seek to examine them – not least because their arguments are still reprised today. For instance, biological race is being reinscribed in genetics (Duster 2005) and advocates of English as the official language of the US are still active (30 US states and at least 19 cities have adopted English as their official language).

The first response to “why critique?” is that it is not unreason or something fundamentally unknowable that is at stake here, but rather the need to examine the very rationality that animates mapping and GIS today. Not only can this rationality be explained, but it can also be challenged, and it is the job of a critical GIS and critical cartography to do just that.

A second question revolves around the historical complicity of mapping and GIS in military, colonial, racist, and discriminatory practices. It is tempting to see maps and GIS as “essentially” complicit and best avoided. Maps are “nothing more” than tools of capitalist expansion and exploitation. (Sometimes one suspects that this tactic explains the silence of those critical geographers we began with. Maps and GIS are embarrassing!)

One popular response is to deny that maps and GIS are “essentially” anything in particular. Maps and GIS are “neutral” technologies that can be used for both good and bad purposes (whatever they are!). On this view we might readily acknowledge the complicity of geography in colonial projects but also point out that maps and GIS can be used to track organ donations, manage global air travel, and empower local communities to fight off Wal-Mart. They are a little like technologies sitting on a shelf, waiting to be pulled down and used. A direct analogy comes to mind here: atomic power. It can be used to build atomic bombs or to power the national grid. We might argue that each one should be judged on its own merits. The same thing goes for mapping, we might then argue. Sometimes maps are used for bad purposes but sometimes they are used for good ones. Those that are, on the whole, bad, we could criticize. Those that seem to be positive we could praise. This results in an economy of morality; a balance between good and bad and which one outweighs the other.

If we take this view, it has the merit of being very flexible. We could assess a range of geosurveillance techniques with it for example (Monmonier 2002b). Monmonier resists the involvement of cartography in anything that might seem “political.” Not surprisingly, when I once asked him about the possibility of there being such a thing as a “political cartographer” in an interview, he replied that he thought it a “glib phrase” and that he “would apply the label political cartographer [only] to people who draw election-district maps” (Monmonier 2002a).

Too often however, this response is just a cover for a do-nothing approach. It is a way of fobbing off the power commitment we make whenever we assert or produce knowledge. This view that maps are politically neutral was recently put forward by the influential National Academies of Science (NAS) in a report entitled “Beyond Mapping” (Committee on Beyond Mapping 2006). The committee was comprised of well-known scholars in GIS, cartography, and geography including Joel Morrison (Chair), Michael Goodchild, and David Unwin. The committee was not unaware of the need to examine the societal implications of GIS and mapping as technologies. For example, they write:

Geographic information systems and geographic information science appear to be benign technologies, but some of their applications have been questioned; as is true of any technology, GIS, though neutral in and of itself, can be used for pernicious ends. (Committee on Beyond Mapping 2006: 47, emphasis added)

A critical approach would argue that this appeal to the neutrality of mapping knowledges is a failure.

The things I have been talking about so far constitute some of the aspects of what Derek Gregory once called “cartographic anxiety” (Gregory 1994). His influential little phrase captures how people sometimes seem to feel about maps. An anxiety is a disorder, and if pronounced enough becomes a subject for psychological investigation – a clinical case. It’s a contrary and split kind of anxiety (a schizophrenic anxiety?), because on the one hand we have maps involved in those colonialist projects, to de- and resubjectify people, or perhaps in which powerful cartographic imagery is invoked to justify an “axis of evil” (Gregory’s more recent work is sustained by a sense of moral outrage at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay [Gregory 2004; Gregory and Pred 2007]). So we’re anxious about using any such uncritical devices that work all too well to establish concrete realities – the unseemly perversity, in the sense of the word as unwanted, not in good taste, out of place.

And then there’s the other kind of anxiety that Gregory talks about; the anxiety of uncertainty which maps and geographical knowledges produce when their authority is undermined. Citing Gunnar Olsson and Brian Harley’s work on “deconstructing” the map (see Chapter 7) Gregory talked of an anxiety (or we might say it is the perversity) that arises when knowledge is destabilized, though he was quick to say it did not mean a descent into “giddy relativism” (can we ask why not?) (Gregory 1994: 73).

So now this anxiety has two contradictory parts – on the one hand maps are incredibly powerful devices for creating knowledge and trapping people within their cool gleaming grid lines, on the other they seem to be nothing at all, just mere bits of fluff in the air.1 Maps are sovereign; maps are dead.

The Third Way?

One might register a few problems with both of these viewpoints howe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Cover: Size Matters

- Chapter 1: Maps – A Perverse Sense of the Unseemly

- Chapter 2: What Is Critique?

- Chapter 3: Maps 2.0: Map Mashups and New Spatial Media

- Chapter 4: What Is Critical Cartography and GIS?

- Chapter 5: How Mapping Became Scientific

- Chapter 6: Governing with Maps:

- Chapter 7: The Political History of Cartography Deconstructed: Harley, Gall, and Peters

- Chapter 8: GIS After Critique: What Next?

- Chapter 9: Geosurveillance and Spying with Maps

- Chapter 10: Cyberspace and Virtual Worlds

- Chapter 11: The Cartographic Construction of Race and Identity

- Chapter 12: The Poetics of Space:Art, Beauty, and Imagination

- Chapter 13: Epilogue: Beyond the Cartographic Anxiety?

- References

- Index