![]()

Chapter 1

The Protagonist

‘Captain One Minute, Pirate the Next’

If you only had 30 seconds I’d tell you:

All innovation is powered by human emotion: anger, paranoia or ambition.

♦

A great innovation process will never compensate for poor innovation people.

♦

The profile of an ideal innovator is a ‘Captain One Minute, Pirate the Next’ – someone who respects their organisation but doesn’t revere it.

♦

They are unreasonably ambitious, relentlessly pushing the boundaries in a way that doesn’t always make sense.

♦

But they’re not egomaniacs; they know when to shut up and listen.

♦

They research as little as possible, and are confident enough in their own judgement to back themselves.

♦

They are team workers, but more than that, they are collaborators.

♦

They’re socially skilled and able to guide others between an expansive world of ideas and a reductive world of decisions.

♦

They’re not necessarily creative, but they are good finishers.

Art has been the Chief Innovation Officer of a global bank for the past year. He oversees a pipeline of about 20 innovation initiatives around the world, each one managed by a team working within its own P&L. Increasingly, Art’s efforts to navigate the company’s internal processes and nudge these initiatives to launch are met with indifference and, in some cases, hostility. ‘It’s like I’m putting a baby in the boxing ring’, Art says of the ideas it’s his job to champion. ‘These projects need more investment and protection.’ Art has started to wonder how much his bank really wants to innovate and – in his darker moments – why he took the job in the first place.

Lillian is the Head of Marketing for one of a global pharmaceutical company’s blockbuster brands. With only 8 years of patent-protected revenue under its belt, Lillian knows her focus should be on innovating new ways to extend the drug’s reach. But she just can’t seem to carve out the time. ‘I feel crushed by the constant need to cover off the senior management’, she says. ‘Every day some junior staffer is asking me to prepare a one-page summary for someone important somewhere. What I need to be doing is getting out of this office and into the marketplace, where I can make a real difference.’ Instead, she and her colleagues spend most of their time trapped in meetings or creating spreadsheets to justify the company’s innovation investments.

John runs the Innovation Centre for a large multinational packaged goods company. He drives development across all regions of a group of brands, and oversees a large team of research scientists, pack-aging developers and marketers. Recently, following a particularly rocky product launch, his company mandated an ‘innovation protocol’. Now each project must pass through a series of gates, with each gate culminating in an all-day review meeting – an event that demands weeks of paperwork and preparation. The top brass fly in for these meetings, which are scheduled up to a year in advance. John doesn’t mind thinking things through, but in his gut he knows innovation doesn’t work like this. ‘It’s as if the organisation has these great grinding wheels of decision-making that slowly turn’, he says. ‘I’m just a little wheel called innovation and I can’t seem to find a way to synchronise with the big wheel.’ To make matters worse, John’s people are starting to jump ship for smaller, less process-driven competitors.

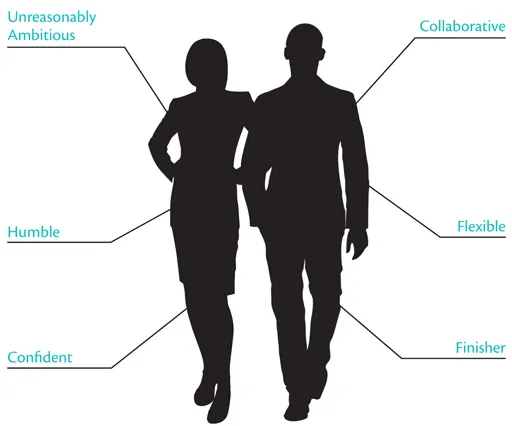

Stories like these are not uncommon. Dig behind innovation and you’ll find people who are frustrated, restless and ambitious. It’s this human energy that drives innovation; people sparking off people. Rarely, if ever, does anyone claim that it was the process or the organisational structure that ‘won it’. The protagonists who pull and push new things through a big company need to have some special qualities to survive the kind of combat they’re about to face. They need an unreasonable dose of ambition. They need to be humble enough to know they don’t have all the answers and yet confident enough to back themselves. They need to be not just great team-workers but also collaborators – and they need to be able to make things happen.

So who is crazy enough to want this job?

‘Captain One Minute, Pirate the Next’

Most successful big-company innovators I meet, whether Chief Innovation Officers, innovation team members or people without an innovation job title but who are tackling a big change project for the first time, have something in common: they respect the organisation they work for, but they don’t revere it. As innovators, they want their businesses to do better, but at the same time they are dissatisfied with the status quo. There’s a kind of ‘love –hate’ thing going on. But too much love and an innovator becomes an ineffective ‘yes-man’. Too much hate and he or she ends up an ineffective loner.

It’s a delicate balancing act. I describe someone who effectively manages it as a ‘Captain One Minute, Pirate the Next’. One minute the innovation leader is the Captain, the passionate man-with-the-plan, standing tall on the bridge of the ship and inspiring us all to go ‘this way’. But the next time you meet, the Captain has morphed into a Pirate. This time he or she is down in the boiler room, sleeves rolled up, shipmates gathered around, using all of his or her cunning to shortcut a process, to subvert the system. Now our protagonist is asking really challenging questions: ‘What if we did it differently? What if we ripped up the way things are done around here? What if?’

So one minute an innovation leader is stubbornly sticking to the big picture; the next he or she is telling you not to sweat the small stuff. I think this intriguing mix of vision and cunning comes from the fact that successful innovators are fixated by outcomes. They are highly motivated to make change happen – so much so that they’re often less bothered about how they get there.

These are the qualities of a ‘Captain One Minute, Pirate the Next’:

To be clear, I’ve never met anyone who scored high on all the traits of a ‘Captain One Minute, Pirate the Next’. The key is to recognise where you or your team are weak and either work at developing new skills or find people to compensate.

Unreasonably Ambitious: Always Pushing the Boundaries

Innovation starts with someone throwing a stone a long way. Innovators are good at this. They know that stretch goals – aiming beyond your own limits – create better performance. They know that their team, brand or organisation needs to work towards a picture of something that’s truly exciting. If this picture doesn’t exist then it’s very hard to do anything other than incremental improvements – small twists and tweaks.

Innovation is literally thrilling. The ambition of an innovation leader and his or her team needs a degree of unreasonableness to it, a feeling of ‘Wow, you’ve got to be kidding – how the hell are we going to do that?’ Successful innovators in large companies aren’t afraid to scare people shitless. When they find themselves surrounded by doubters, they develop a big fat grin – they know they’re on the right track.

Axe, or Lynx depending on where in the world you live, is one of Unilever’s leading brands and a good example of this approach. The Axe line-up of grooming products includes body sprays, deodorants, antiperspirants, shower gels, shampoos and styling products and claims to ‘give guys confidence when it comes to getting the girl’.

In 2002, inspired by a scene from The Matrix in which the protagonist is offered the choice of a life-changing pill, newly appointed brand director at Unilever, Neil Munn, created the ‘Republic of Axe’. This was a bold new brand culture within Unilever that had its own laddish identity. ‘We needed walls’, said Munn. ‘Inside was our vibe, our beat.’ Fuelled with the excitement of being a renegade team, bent on helping young men get ahead in the mating game, Axe has enjoyed strong growth each year with wave after wave of award-winning advertising driving successful new products (such as Anti-Hangover shower gel that ‘gets the night out of your system’).

This innovation journey, of course, hasn’t been all plain sailing. In its wake are discarded and banned TV commercials. More than once Unilever has apologised online for going ‘too far’ with Axe, thus guaranteeing cult status amongst young men the world over. How did Unilever, a megasized company famous for sensible household brands such as Surf, Persil and Knorr, manage to spawn such a maverick tribe?

“

To be entrepreneurial in a large company you can’t be afraid to leave

Munn, who left the brand in 2006, says ‘I had to defend the brand, and my boss (the President of Unilever Deodorants category) had to give me air cover. Without this we wouldn’t have had the space and the confidence to flex our muscles and experiment – the brand is all about pushing it.’ Munn also created an ambitious and powerful allegorical device that became iconic throughout the business: instead of just ‘joining the team’, new members had to agree to ‘take the red pill’. This is a commitment to rapid and audacious decision-making that is played out daily in the Axe Republic (i.e. brand offices throughout the world) where decisions aren’t supposed to be safe. In a characteristic move, Munn once presented his annual plan on video while having a massage; an unusual move, but entirely appropriate to the brand.

Finally, Munn admits to several moments where he thought he’d pushed the mothership too far but ‘to be entrepreneurial in a large company you can’t be afraid to leave’, says Munn, ‘the dynamic in megacorps isn’t about fast decision-making, so our view was that we were going to just get on with things unless we were told to stop, which we never were’.

Large companies are like supertankers; they have a need to be predictable because their owners don’t like surprises. They are very good at moving in one direction at a steady pace but often poor at turning quickly and exploring uncharted seas. The story of Axe is highly instructive. It tells us that innovation needs a rebellious band bent on doing things differently; think of it as an anticultu...