![]()

1

Seafood quality, safety, and health applications: an overview

Cesarettin Alasalvar, Fereidoon Shahidi, Kazuo Miyashita, and Udaya Wanasundara

1.1 Introduction

In 2007, the world’s fish production was around 145 million tonnes, valued at approximately US$92 billion. Of the total amount of production, approximately 75% was used for human consumption and the remaining portion used to produce fish meal and fish oil or discarded [1,2]. With more than 30,000 known species, fish form the largest group in the animal kingdom used to produce animal-based foods. Only about 700 of these species are commercially fished and used for food production [3]. Moreover, several species of crustaceans, molluscans, and seaweeds, as well as microalgae, are used as food for humans. Devising strategies for full utilization of seafoods and their by-products to produce value-added novel products (e.g. long chain omega-3 (n-3 or -3) fatty acids, specialty enzymes, protein hydrolysates, peptides, chitin/chitosan, glucosamine, squalene, collagen, carotenoids, etc.) is of great interest.

Some important aspects such as quality, safety, and health effects of seafoods are considered in this book. These factors contribute to optimal utilization of the marine resources together with the consequent maximization of health benefits. This overview chapter highlights these important aspects of seafoods.

1.2 Seafood quality

When seafoods are consumed, their quality is perceived through the conscious or subconscious integration of their sensory or organoleptic characteristics. These characteristics may be grouped as appearance, odour, flavour, and texture [4]. In most cases, the first opportunity to evaluate the quality of seafood is governed by its appearance. This is true whether we see the fresh product through a display counter or in a packaged container. Much of the favourable response to the appearance of seafood may be achieved by selecting proper packaging and display.

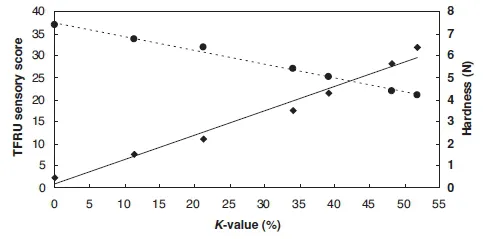

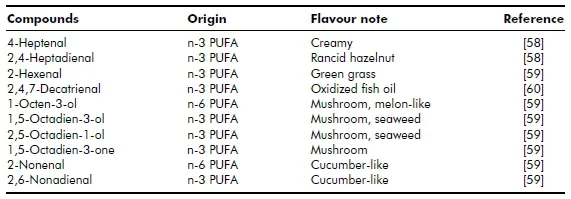

The odour of freshly caught fish is mild and described as typical of the “sea” and “seaweed”. If fish is held in ice from the time of catch, it retains its high quality for about one week or longer. During this period, no objectionable “fishy” odour develops [5]. However, long-term storage may lead to the development of an undesirable “fishy” odour due to the formation of trimethylamine (TMA), dimethylamine (DMA), total volatile base nitrogen (TVBN), ammonia, volatile sulphur compounds, and other undesirable compounds characteristic of microbial spoilage [6–11] Several other chemical methods are currently in use for the quality assessment of seafoods [11,12]. Of these, biogenic amines [13,14], adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP)-breakdown compounds, and K-related values (Ki, G, Fr, H, and P-values) [15,16] are the most common and provide accurate quality indices. Figure 1.1 shows the correlation between K-value, sensory scores, and hardness [12]. In addition to the above mentioned oxidation products, unsaturated fatty acids present in seafoods can lead to a wide range of lipid oxidation products such as peroxides, carbonyls, aldehydes, alcohols, and ketones, and their interaction compounds that contribute to the odour of the stored seafoods [17]. Table 1.1 shows the various carbonyl compounds derived via lipid oxidation in fish tissues.

Fatty fish such as mackerel, herring, salmon, and sardines have more flavour than lean fish such as cod, haddock, and hake. The flavour of fatty fish is pleasant as well as unique, but only while the quality is good. However, due to high fat content, these fish can undergo rapid oxidation and develop rancid/oxidized flavours that are objectionable to most people. The off-flavours that develop in the different species have different effects on the organoleptic acceptability of the products [4].

The final criterion used in the organoleptic evaluation of seafood is texture, which is related to the physical properties that are experienced during biting and chewing. Although this criterion is more relevant when applied to cooked fish, texture tests are made routinely by inspectors on raw fish, because that is a good indicator of the texture of cooked seafood.

Crude marine oil is a by-product of the fish meal industry and is considered a good source of nutritionally important long-chain n-3 fatty acids, especially eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). However, crude oil should be further processed to improve its quality characteristics as well as its shelf-life [18]. The basic processing steps of crude marine oil are degumming, alkali-refining, bleaching, and deodorization [19]. During processing, impurities such as free fatty acids (FFA), mono- and diacylglycerols (MAG and DAG), phospholipids, sterols, vitamins, hydrocarbons, pigments, proteins and their degradation products, suspended mucilaginous compounds, and oxidation products of fatty acids are removed from the crude oil. Processing of marine oils is similar to that of vegetable oils; however, the quality of crude marine oils is less uniform than crude vegetable oils. High quality crude oils may be obtained by proper handling of raw material, such as minimizing damage to fish and proper chilling after landing [20]. The degree of unsaturation of the fatty acids makes them extremely vulnerable to oxidative degradation [21,22]. Volatile compounds generated upon oxidation of such fatty acids contribute to the unpleasant flavours and odours of the oil and the food products containing such oil. Oxidation of the double bonds in unsaturated fatty acids in the oil can occur in the basic processes of autoxidation, photo-oxidation, and thermal oxidation [23]. A basic knowledge of these oxidation processes is required to understand the mechanism of the deterioration of the quality of food grade fish oil. The nature of oxidation, as well as to what extent this occurs, depends upon the chemical structures of the fatty acids involved, and other constituents, even if in minor quantities in the product, as well as the conditions of handling, processing, and storage. Physical factors such as the surface area exposed to oxygen, oxygen pressure in the surrounding environment, temperature, and irradiation can contribute to the oxidation of fatty acids [24]. The origin of the off-flavours is in the breakdown products of hydroperoxides of the highly unsaturated lipids in fish and/or fish oil.

In this book, several approaches are described to protect unsaturated fatty acids from oxidation. Extreme care must be practised, especially during handling, processing, transferring and transporting, packaging, and storage of oil, to minimize oxidation through exposure to unfavourable conditions. High temperatures should be avoided in processing and the fish or fish oil should never be exposed to oxygen and light. Processed oil containing unsaturated fatty acids should be stored in the dark, at or below −20◦C, under an inert gas such as nitrogen or argon. Besides preventive measures, antioxidants and related compounds also can be used to retard the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids in fish oil. These compounds may have different inhibitory activities in the protection of oils against the oxidation process. Microencapsulation of fish oil into a stable flowable powder extends the shelf-life and prevents the oxidative deterioration of unsaturated fatty acids [25].

1.3 Seafood safety

Quality and safety are important parameters for perishable foods such as fish and fish products. About one-third of the world’s food production is lost annually as a result of microbial spoilage [26]. Food safety cannot be assured by inspection alone and knowledge of factors that influence growth, survival, and inactivation of pathogenic micro-organisms is an essential element in the design of processing, storage, and distribution systems that provide safe seafoods [27].

The flesh of healthy and live fish is generally thought to be sterile, as their immune system prevents the growth of bacteria [28,29]. When the fish dies, the immune system stops functioning and bacteria can proliferate freely. Bacteria can be either of the spoilage type or the pathogenic type. Spoilage is defined as the sensory changes resulting in a fish product being unacceptable for human consumption. It is caused by autolytic and chemical changes or off-odours and off-flavours due to bacterial metabolism [28,30]. Some of the major spoilage bacteria in seafood are Pseudomonas spp., H2S-producing bacteria, Shewanella spp., Enterobacteriaceae, lactic acid bacteria, Photobacterium phosphoreum, and Brochothrix thermospacta among others [30-37]. Pathogenic bacteria associated with seafood can be categorized into three general groups:

1) bacteria (indigenous bacteria) that belong to the natural microflora of fish (Clostridium botulinum, pathogenic Vibrio spp., Aeromonas hydrophila);

2) enteric bacteria (non-indigenous bacteria) that are present due to faecal contamination (Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., pathogenic Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus); and

3) bacterial contamination during processing, storage, or preparation for consumption (Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium perfringens, Salmonella spp.) [30,38-40].

Standard (traditional) methods for recovering micro-organisms from seafood include enrichment culture, streaking out onto selective or differentiating media or direct plating onto these, and identification of colonies by morphological, biochemical, or immunological tests [41]. These methods require a lot of human labour, are costly, and usually take between two and five days. In contrast to standard methods, molecular methods allow the rapid detection and identification of specific bacterial strains and/or virulence genes without the need for pure cultures. They are mainly based on oligonucleotide probes, polymerase chain reactions (PCR), or antibody techniques [30,41–43]. The use of probes and PCR in seafoods has increased dramatically in recent years. Gene probes and PCR primers for detecting and identifying almost every food-borne pathogenic bacterial species have been developed.

As mentioned above, when harvested in a clean environment and handled hygienically until consumption, fish is very safe. Unfortunately, unhygienic practices, including insufficient refrigeration and sub-standard manufacturing practices, can be at the origin of many outbreaks of fish-borne illnesses. Fish-borne illnesses can be broadly divided into fish-borne infections and fish-borne intoxications (Table 1.2). In the first case, the causative agent (bacteria, viruses, or parasites) is ingested alive and invades the intestinal mucous membrane or other organs (infection) or produces enterotoxins (toxi-infection). Protection from the environment, personal hygiene, education of fish handlers, and water treatment (e.g. chlorination) are therefore essential in the control of fish-borne diseases. In the case of intoxications (microbial, biotoxin, and chemical), the causative agent is a toxic compound that contaminates the fish or is produced by a biological agent in the fish. If the agent is biological, intoxication can occur even if the agent is dead, as long as it has previously produced enough toxins to precipitate the illness symptoms [2].

Table 1.2 Types of fish-borne illness. Adapted with permission from FAO [2]

| Infections | Bacterial infections | Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, Vibrio vulnificus, Shigella spp. |

| | Viral infections | Hepatitis A virus, Norovirus, Hepatitis E. |

| | Parasitic infections | Nematodes (round worms), Cestodes (tape worms), Trematodes (flukes) |

| | Toxi-infections | Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, E. coli, Salmonella spp. |

| Intoxications | Microbial | Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium botulinum |

| | Biotoxins | Ciguatera, Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP), Diarrheic (DSP), Amnesic (ASP), Neurotoxic (NSP), Histamine |

| | Chemical | Heavy metals: Hg, Cd, Pb. Dioxines and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Additives: nitrites, sulphites |

1.4 Health applications of seafood

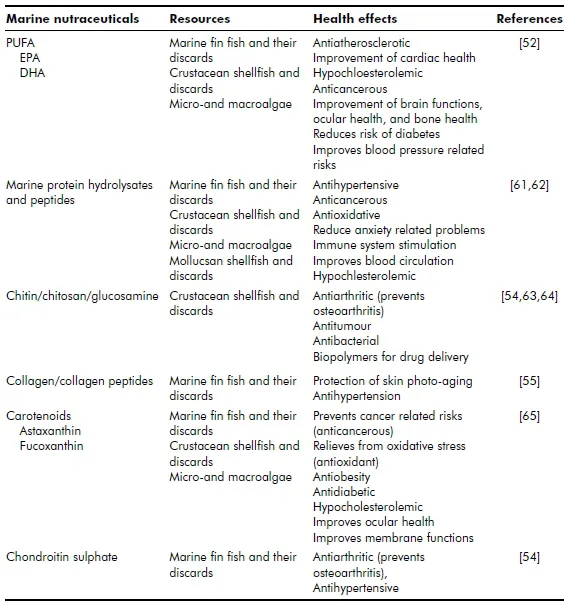

The unique and phenomenal biodiversity of the marine environment contributes to the presence of a large pool of novel and bioactive molecules. Epidemiological studies have established a positive correlation between marine food consumption and a reduced risk of common chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancers [44–48]. The health beneficial effects of some marine bioactives have been made clear on the basis of nutritional and nutrigenomic studies [49–53]. Thus, dietary marine products are expected to prevent several diseases. Although perception of the term “marine nutraceuticals” to the health care professionals and consumers is still largely limited to popular fish oils rich in highly unsaturated n-3 fatty acids, research has also been shifted to other marine bioactives such as collagen, peptides, chitin, chitosan, chitosan oligomers, glucosamine, carotenoids, and polyphenols, etc. Exciting developments in nutrigenomics and the human genome project, combined with formulation of food products containing specific marine bioactives, will create new industrial opportunities for food and pharmaceutical companies. Advances in biotechnological processes and their application to the food industry have resulted in commercial success, as seen in the case of glucosamine [54] and collagen [55]. Therefore, we have strong expectations for the further growth of both research and commercialization of marine nutraceuticals and marine functional foods.

In earlier days, fish sources appeared to be inexhaustible and by-products arising from fish processing were considered worthless and routinely discarded. The discovery and development of marine nutraceuticals has changed the commercial value of fisheries processing by-products. Various fish and shellfish source materials such as skin, scales, frame bones, fins, visceral mass, head, and shell are now utilized to isolate a number of bioactive commodities. Marine algae, including micro- and macroalgae, are also good resources for other marine bioactive materials (Table 1.3).

Marine lipids generally contain a wider range of fatty acids than terrestrial plants and animals [56]. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), such as EPA and DHA, are typical of marine lipids, whereas n-6 PUFA, mainly linoleic acid (LA), is predominant in common vegetable oils. The importance of EPA and DHA in human health promotion has been confirmed through research. Although many papers have been published on the health beneficial effects of EPA and DHA, there is still an increased level of interest in nutritional and health related issues associated with EPA and DHA as well as other highly unsaturated fatty acids, such as stearidonic acid (SA; 18:4 n-3) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA; 22:5 n-3).

Marine foods and their processing discards/by-products, micro- and macroalgae, and marine microbes are major potential sources of EPA and DHA. They are also important sources of other functional biomaterials such ...