![]()

Part One

What is a brand?

![]()

Introduction

I believe we must consider a brand’s behaviour, not just what a brand is

Mark Earls Herdmeister, Herd Consultancy

It’s... bigger on the inside. (DR WHO)

The questions we ask reveal far more than you’d think: not just the answers we hope to uncover, but more fundamentally the ideas we have about the world and how things are.

Someone who asks how God could allow terrible things to happen to themselves, to their family or to innocent victims of a natural disaster half the world away reveals not only the assumption that there is a such a thing as a divinity, but also that said super-being has some kind of control over what happens in the world or, indeed, that he/she/it tends to keep good and evil in balance, rewarding the good and protecting them from bad stuff.

In other words, the kinds of questions we ask reveal an awful lot more than we imagine they do. They are – in the famous words uttered by all those entering Doctor Who’s Tardis – ‘bigger on the inside than on the outside’.

Over the years, all discussions of the idea of brands and branding have tended to start with the same simple four-word question: what is a brand?

What does this question tell us about the ideas and assumptions floating around in the background?

Well, first off, perhaps it presumes that there is such a kind of thing as a brand, that it’s a thing like a poster, or a promotion or an advert. Second, that such a definition can be definitive, universal and long-lasting. Third, and perhaps most telling, that there’s a need to provide a definition.

A different kind of question

What’s fascinating about the excellent pieces that follow, is that none of them ask this kind of question at all. Which is curious, given that after 10 years of the Excellence Diploma we still start the programme with this question.

Instead, the striking thing about all of the different points of view which we’ve collected here, is that they focus more on what you might do in the modern world than in defining the concept precisely – whether that direction is informed by new insights from the behavioural and cognitive sciences (as, for example, John Willshire’s ‘Communities are the future of brand communications’ does), new emerging ways of engaging with people beyond the narrow confines of advertising and marketing (Graeme Douglas’ ‘Brand new religion’ or Tim Jones’ excellent ‘Gaming your brand’), or just by a pragmatist’s wisdom and acceptance not to overthink things.

Unlike their predecessors, these new voices don’t seem to need the security of a reductionist definition of this brand thing – a statement of initial conditions, if you like. They seem perfectly happy to accept that arguing the toss about what a brand is less interesting than getting on with the messy but exhilarating act of brand-building. As one essay (Nick Docherty’s ‘Brand is a word that has outlined its usefulness’) puts it: ‘how helpful are the concepts of brand and branding as they are currently used?’

Rather than be confused by all this theoretical definitional wheel spin, these practitioners are working through ways to get on and make a difference.

Each of the authors quickly tells us what they believe a brand to be, but use that definition to explore how that changes how a brand should engage.

These are informed and thoughtful practitioners (not dumb do-ers), but not would-be theorists. And that is a good thing for the industry, surely.

What lies beneath

All of which serves to reveal a bigger and more important shift than we’re seeing elsewhere in marketing and advertising, for example it informs the work the IPA Social Works Group is trying to bring the same kind of rigour to understanding social media effectiveness as has been developed for mainstream advertising.

Put simply: we are in transit from a world of stable certainties to one of fluid multiplicities. From a largely unchanging landscape that merely needed detailed observation to describe exhaustively, to one that is rich, complex and ever-changing.

In media terms, this means we’re not switching from a world of TV and print to one that is now and forever dominated by Twitter and Facebook (although I’m sure they’d secretly like us to believe that). No, the newer technologies are both additive and at the same time provisional – they will in turn be superseded themselves. ‘Facetube’, as my father-in-law calls it, is not the final word.

The works collected here describe really useful ways of thinking about brands and brand-building in this new, messier, constantly changing landscape.

The rise of ‘WE’ and other things

All of which is not to say that there aren’t any consistent content themes that emerge from these excellent pieces of work.

Given my own efforts over the last decade,1 I’m particularly gratified to see the widespread adoption of what I’ve called the HERD insight – the notion that we humans are fundamentally social creatures and that our behaviour is shaped by the behaviour of those around us (certainly much more than we’d imagine). This serves variously to recast the nature of a brand as a knowledge centre and editor (‘The communis manifesto’ by John Willshire), challenge the structure of the consumer–brand relationship (David Bonney and the rise of ‘WE’ brands) and delve into the nature of brand experiences and how to build them (Ian Edwards and open-source innovation and Graeme Douglas’ essay ‘Brand new religion’).

Equally, there is an intriguing golden thread that runs through many of these papers about brand as a user-led concept. While none of the authors are crass enough to mention Jeremy Bullmore’s famous metaphor of brands being built by consumers as birds build nests, the user-perspective lies at the heart of all of these papers. Which is refreshing to those of us bored and frustrated by company-led definitions of brands (‘it’s what we tell them it is’) and all the more so, given how naturally it is expressed.

A new hope

So, for those Jeremiahs bewailing the end of advertising or some such, these kinds of essays, with their very practical and thought-through prescriptions, are a breath of fresh air.

Or, then again, maybe not: it’s curious that such an apparently simple question, can lead to such practical and fresh directions for the future.

Notes

1 Earls, M and Bentley, A (2011) I’ll Have What She’s Having: Mapping social behaviour, MIT Press, US; and Earls, M (2009) Herd: How to change mass behaviour by harnessing our true nature, John Wiley & Sons.

![]()

01

I believe brand is a word that has outlived its usefulness

2005/06

Nick Docherty Global Planning Director, Wieden + Kennedy Amsterdam

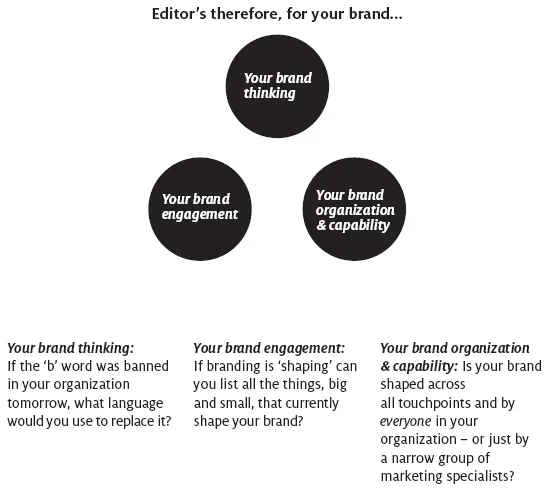

I believe ‘Brands’ and ‘branding’ are words that have outlived their usefulness, deriving as they do from a time when they referred to static badges and didactic communications. I believe that their roots are now a cause for confusion, and that the terms ‘morph’ and ‘shaping’ do a more intuitive job of explaining the things that we all do in our roles as marketing professionals.

...and author’s personal therefore

In retrospect, the Diploma’s real value to me was in helping me first understand, and then challenge, the theoretical underpinnings of everything that we do as an industry. It made me read all the books that I never would have otherwise read, and then rip them up (Byron Sharp’s peerless How Brands Grow aside, it turns out that marketing textbooks are mostly a colossal waste of paper). It allowed me to get the over-thinking out of the way and get on with the serious business of doing. Which shouldn’t be confused for doing without thinking. That’s something else entirely.

So, is what I believed then the same as what I believe now? Not really, and I would be colossally disappointed if that wasn’t the case. What I do believe is that the very last thing marketing needs is yet another definitive right answer to the issues it faces. But what has endured for me is an attitude and approach that challenges assumptions and believes in the primacy of real-world practice over intellectual theory. That takes to heart the old military adage that no plan ever survives contact with the enemy, but acknowledges the need for a decently thought-through plan in the first place – and an ability to argue its merits with equally informed people.

Here’s a brief overview of how my drive to do more, and over-think less, has shaped my life and career over the last decade. They are in the form of some general principles rather than rigid commandments.

Work: learning is doing

We humans are a pretty conservative bunch. In a world built on shifting sands we cling to what we know, treat received w...