![]()

Part I

Journeys for Peace

Chapter 1

An African American Abroad

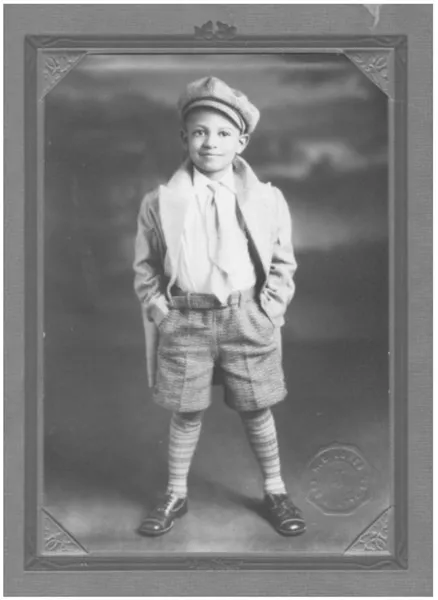

There is a wonderful picture of Bob Browne, taken when he was perhaps five years old. It must have been close to 1929, when the United States was on the verge of the worst economic depression in the country’s history. You would not know it, though, from this sepia-toned image. Browne is dressed to the nines, clearly marking him as the child of a comfortable, even well-to-do, family. Almost everyone who lived in “Bronzeville,” the segregated black neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, went to Mr. Jones to have their picture taken.1 Most children found their nicest outfits to be uncomfortable. Furthermore, Mr. Jones brooked no nonsense. Browne’s half sister Wendelle, who was nine years older and in her early teens, recalled her sense of intimidation before the photographer’s commanding presence.2 In contrast, her brother did not want to be posed. Out of sheer spunk, he asked if he could show Mr. Jones how he wanted to stand. So the final image shows the young boy as he wanted to express himself. In addition to his dapper clothes, he wears a huge, confident smile as he looks directly into the camera. Looking at this picture, one thinks, “Look out world, here he comes!”

Robert Span Browne, whose life bridged nearly eight decades from the 1920s to the early years of the twenty-first century, circumnavigated the globe several times as he traveled and lived in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America.3 Growing up during the Great Depression, he reached adulthood during World War II and spent the middle decades of his life in the midst of the Cold War, the black liberation struggles in the United States, and the decolonization movements of the so-called Third World.

Figure 1. Bob Browne as a young boy. Personal collection of the Browne family.

Browne was on the front lines of these dramatic social changes. During the crucial years of 1955–1961, when the United States escalated its military, political, and economic commitment to containing communism in Southeast Asia, Browne worked as an American aid adviser, first in Cambodia and then in South Vietnam.4 Upon his return to the United States, he became a leading and not yet fully recognized figure in two of the major movements of the 1960s and 1970s: the protests against the U.S. war in Southeast Asia and the black power movement that sought economic, political, and cultural autonomy for people of African descent, both in the United States and in the broader black diaspora.5

Despite Browne’s political accomplishments, he is not acknowledged among the pantheon of antiwar or black liberation leaders.6 His omission is rather striking, because he was a key and visible figure in the antiwar movement. As he reflected, “I was the one Black who had been connected with that movement before prominent Blacks like Martin Luther King, Julian Bond, and Dick Gregory eventually spoke out.”7 In fact, Browne’s absence from the historical record renders the peace movement even more “white” than it actually was. Not only are Browne’s contributions as an African American activist slighted, but his personal and political partnerships with Vietnamese individuals also receive little historical attention. Examining Browne’s political contributions sheds light on African American and Asian peace activism that shaped the broader U.S. antiwar movement.

African Americans have long had internationalist aspirations. Their marginalized status in the United States fostered not only desires for full citizenship but also an interest in linking their struggles for equality with those of racialized and colonized others on the global stage. Yet as various scholars remind us, African American internationalism waxed and waned based on historical context. Also, like all complex political ideas and movements, various individuals and organizations espoused different analyses and goals. Bob Browne’s early life, then, provides a window into how a member of the black middle class developed an internationalist outlook as he came of age during the Great Depression, World War II, and the early Cold War.

Historian James Meriwether, in his study of African American relationships with Africa, identifies three main explanations for African American internationalism. The “bad times” thesis suggests that “African Americans promote stronger ties with Africa when they feel more alienated in the United States.”8 In contrast, what might be characterized as the “good times” argument posits that “as blacks in America increase their confidence in their status as Americans, they feel greater comfort in looking to Africa.”9 Meriwether critiques these two arguments for focusing exclusively on the U.S. context. In contrast, he suggests that historical developments in Africa during the 1930s through the 1960s, particularly the efforts to resist colonization and obtain independence, changed the perspectives of African Americans toward their ancestral continent.

Browne’s early life in the United States and abroad indicates that all three explanations help to explain his internationalist outlook. As a member of the black middle class coming of age during World War II, Browne had aspirations for and some access to educational and professional achievement. At the same time, the persistence of Jim Crow, in both the North and the South, eventually led Browne to leave the United States out of frustrated hopes. As an African American overseas, he faced constraints and also gained access to unique opportunities in the context of the early Cold War. Furthermore, Browne’s gender facilitated his ability to embark on world travels. And, through his experiences while traveling in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East in the early 1950s, Browne developed a deeper appreciation of American race relations, international politics, and the possibilities for his life and career.

In many ways, Browne’s early life qualified him as a member of the “talented tenth.” This term, coined by scholar and activist W. E. B. DuBois, describes the educated elite among African Americans who provide leadership and service to their people. Browne grew up in a segregated but vibrant community, the South Side of Chicago, where he absorbed a love of politics and people.10 Coming of age in the Great Depression, he also developed a fascination for economics, a social conscience, and a sense of social responsibility.

Bob Browne’s father, Will Browne, was born in Buffalo, New York, but had become a longtime resident of Chicago by the time his children were born.11 Bob described Will Browne as “a modest functionary of the municipal government.”12 His half sister Wendelle explained that their father was a “civil service employee. . . . In those days, if you paid your water bill personally, you had to meet him. He was in room 101, City Hall.”13 Will’s position was secured through the widespread practice of political patronage in Chicago, which operated primarily among the city’s white residents but extended, to a much smaller degree, to African Americans.14 Like many African Americans at the time, the Brownes were Republicans because that was the party of Lincoln. The Democrats, on the other hand, represented “the Southerner . . . the oppressive lynchers of black people.”15 Although black voters began shifting their support toward President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the Great Depression, Republicans tended to dominate the Illinois elections and hence patronage networks. Even so, Will Browne was among a small black elite to benefit from these political connections. He seemed to have a deep interest in politics, though, beyond the financial remuneration of a civil service position. Will Browne did not attend college, but his daughter described him as “a political analyst” with “a very excellent mind. . . . Every time when I saw him, which was about two or three times a month, he would tell me about what was happening in the nation.”16

Browne seemed to have absorbed this love of politics from his father. In high school, Browne “became an avid reader of The Chicago Defender,” a premier black newspaper in the country.17 Through the paper, Browne “soaked up” news about “the indiscriminate lynching of blacks, especially in the South”; he also learned of the “non-life-threatening injustices inflicted upon blacks, both in the South and the North.”18 In addition, the Defender introduced him to black literature. When Richard Wright’s novel Native Son was released in 1940, Browne read it “within months of its publication”; the novel “held a special attraction . . . because its locale was just a few blocks from [his] home in Chicago.”19 The Defender also exposed Browne to the leading African American political figures of that time: Mary McLeod Bethune, a member of the so-called Black Cabinet who advised President Roosevelt on issues related to race; the executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Walter White; the renowned scholar and NAACP founder W. E. B. DuBois; and the Renaissance man—athlete, actor, singer, and activist—Paul Robeson.20

While Will Browne shared his passion for politics with his children, Julia Browne, Bob’s mother, made sure that her children learned manners, “a strict, inflexible code of moral conduct,” as well as a love of people.21 Remembered as “a very attractive and highly stylish woman” by her son, she not only focused on the appearance of her children but also wanted to shape their character and behavior.22 Julia was from the South. Born in Atlanta, Georgia, and raised in South Carolina, she came to Chicago as part of the great migration of over a million and a half African Americans who moved to northern urban centers between 1910 and 1930.23 They came seeking better economic opportunities and hoping for better lives, away from Jim Crow laws, lynchings, and sharecropping. Julia Browne did not come from the poorest family. Wendelle believes that “they were better off than the average,” because Julia “was able to go to boarding school.”24 Even so, “her memories of the South were very, very bitter. . . . She had seen things . . . that made [her never] want to . . . go back.”25

In Chicago, both longtime residents and newer migrants continued to be shaped by racial discrimination, as evidenced by the pattern of residential segregation. Bronzeville, swelling with the influx of new migrants, became the “second largest Negro city in the world” in the 1940s, second only to Harlem.26 With limited housing options beyond the South Side, Bronzeville became home not only to working-class African Americans but also to the middle- and upper-middle classes, who collectively constituted approximately one-third of the population.27

Class was tangible in ways that Bob Browne recognized. Although he described himself as being “born into a lower middle class black family,” Browne recalled that his family “had a telephone, which many people in the neighborhood did not. In fact, a couple of our neighbors would regularly come over and ask if they could use our telephone.”28 In addition, they had a car, which his mother drove, a “somewhat . . . daring practice for a woman in the mid 1920s.”29 Wendelle described her father and half siblings as living in the Woodlawn section of Bronzeville, close to Washington Park, where families tended to own their own homes and “the cutest kids came from.”30 Bronzeville residents used to think, “Well, if you lived in Woodlawn—nice, nice.”31

In Bronzeville, Julia was known as a gracious hostess, and Bob Browne inherited his mother’s affinity for cultivating positive social relationships. As his stepsister recalled, he was “interested in people. . . . He just liked to know people.”32 In Browne’s youth, his social network mainly included other members of the black middle class in South Side Chicago. Although he worked a variety of odd jobs to earn pocket money and even to help support his family after his father’s death, Browne described himself as leading an “appallingly bourgeois” life: “My teen age crowd was used to throwing and attending lavish formal dances several times a year, for which we rented tuxedos and/or tails, bought our dates corsages, and behaved pretty much as we felt middle class white folks did, except that our music was infinitely better.”33 His cohort of black middle-class teenagers included individuals who would become prominent intellectuals and artists. Jewel Plummer Cobb became “the first black woman to be named president of a major white university,” namely California State University, Fullerton. Browne also socialized with the family of “Lorraine Hansberry, author of A Raisin in the Sun.”34 Hansberry’s parents were known for throwing “fabulous New Years Eve” parties. Browne recalled Lorraine criticizing “the glamorous displays of conspicuous consumption such as these super-parties exhibited”; he, in contrast, reveled in these occasions, particularly for the opportunities to mingle with celebrities like Paul Robeson, “who usually stayed with the Hansberry family” during visits to Chicago.35

Despite his relatively privileged background, Bob Browne recalled that coming of age during the Depression years made economics particularly fascinating to him. In his memoir, he describes in great detail:

One recollection from this period which has never dimmed over the past seven decades. It inflicted a scar on my brain which shaped my every economic decision and stalked my every expenditure, at least until the time of my retirement. The precipitating event must have taken place about 1932 or 1933, during the early years of the great depression, when I was perhaps 8 or 9 years old. I was aware that times were very hard, that there were many people who did not have enough to eat, and even that people were being put out of their homes because they had no money to pay the rent. One heard about such happenings on the radio and they were spread across the newspapers and the movie house newsreels. But walking home from school one day, passing a sm...