![]()

Part 1

The psychology of engagement

![]()

1 What is engagement?

Wilmar B. Schaufeli

Introduction

Everyday connotations of engagement refer to involvement, commitment, passion, enthusiasm, absorption, focused effort, zeal, dedication, and energy. In a similar vein, the Merriam-Webster dictionary describes the state of being engaged as ‘emotional involvement or commitment’ and as ‘being in gear’. This chapter focuses on engagement at work, a desirable condition for employees as well as for the organization they work for. Although typically, ‘employee engagement’ and ‘work engagement’ are used interchangeably, this chapter prefers the latter because it is more specific. Work engagement refers to the relationship of the employee with his or her work, whereas employee engagement may also include the relationship with the organization. As we will see below, by including the relationship with the organization, the distinction between engagement and traditional concepts such as organizational commitment and extra-role behavior becomes blurred.

Although the meaning of engagement at work may seem clear at first glance, a closer look into the literature reveals the indistinctness of the concept. As with many other psychological terms, work engagement is easy to recognize in practice yet difficult to define. In large part, as Macey and Schneider (2008: 3) argued, the confusion about the meaning of engagement ‘can be attributed to the “bottom-up” manner in which the engagement notion has quickly evolved within the practitioner community’. However, this bottom-up method that flourishes in business is not only at odds with the top-down academic approach that requires a clear and unambiguous definition of the term, but it also hampers the understanding of work engagement for practical purposes. A Babylonian confusion of tongues precludes a proper assessment, as well as interventions to increase work engagement. Therefore the first chapter of this volume tries to answer the crucial question: ‘What is engagement?’

The structure of the chapter is as follows. First, a brief history is presented of the emergence of engagement in business and in academia (section 1), which is followed by a discussion of various definitions that are used in business and in science (section 2). Next it is argued that engagement is a unique construct that can be differentiated, for instance from job-related attitudes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and from work addiction and personality dispositions (section 3). The most important theoretical frameworks are discussed that are used to explain engagement (section 4) and the organizational outcomes of engagement are elucidated (section 5). The chapter closes with some general conclusions and an outlook on the future of this intriguing psychological state (section 6).

The emergence of engagement in business and academia: a brief history

It is not entirely clear when the term ‘engagement’ was first used in relation to work, but generally the Gallup Organization is credited for coining the term somewhere in the 1990s. In their best-selling book First, break all the rules, Buckingham and Coffman (1999) summarized survey results that Gallup had obtained since 1988 on ‘strong work places’ of over 100,000 employees. Employees’ perceptions of such workplaces were assessed with a ‘measuring stick’ consisting of 12 questions. Later this tool became known as the Q12, Gallup’s engagement questionnaire (see below). The term engagement is only occasionally used in the book by Buckingham and Coffman (1999) that was basically about leadership, as is reflected by its subtitle What the world’s greatest managers do differently.

Table 1.1 Changes in the world of work

Traditional | Modern |

Stable organizational environment | Continuous change |

Uniformity | Diversity |

Life-time employment | Precarious employment |

Individual work | Teamwork |

Horizontal structure | Vertical structure |

External control and supervision | Self-control and self-management |

Dependence on the organization | Own responsibility and accountability |

Detailed job description | Job crafting |

Fixed schedules and patterns | Boundarylessness (time and place) |

Physical demands | Mental and emotional demands |

Experience | Continuous learning |

Working hard | Working smart |

Around the turn of the century, other major consulting firms followed suit. Obviously, the time was ripe and engagement was ‘in the air’. But why was that so? Why did companies suddenly become interested in work engagement after the turn of the century? Although it is difficult to come up with an unambiguous answer, it can be speculated that a set of changes that were – and still are – taking place in the world of work constitute the background for the emergence of engagement in business. Table 1.1 summarizes the major changes that are related to the ongoing transition from traditional to modern organizations.

Taken together, these changes boil down to what can be called a ‘psychologization’ of the workplace. That is, most of the current changes that are listed in Table 1.1 require a substantial psychological adaptation and involvement from the part of employees. In other words, more than ever employees need psychological capabilities in order to thrive and to make organizations survive. For instance, organizational change requires adaptation, diversity requires perspective taking, teamwork requires assertiveness, working in vertical networks requires communication skills, job crafting requires personal initiative, boundarylessness requires self-control, and mental and emotional demands require resilience.

The bottom line is that more than in the past the employee’s psychological capabilities, including their motivation, is taxed. Instead of merely their bodies, employees in modern organizations bring their entire person to the workplace. Or as David Ulrich has put it in its best-selling book Human resource champions:

Employee contribution becomes a critical business issue because in trying to produce more output with less employee input, companies have no choice but to try to engage not only the body, but also the mind and the soul of every employee.

(1997: 125)

Ulrich makes two points here. First, the organization’s human capital becomes increasingly important because more has to be done with fewer people. So, people matter more than they did in the past. Second, modern organizations need employees who are able and willing to invest in their jobs psychologically. And this is exactly what work engagement is all about. No wonder that companies became interested in engagement at a time of profound changes in the world of work.

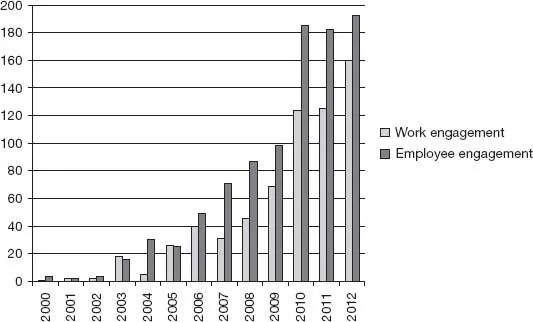

Figure 1.1 | Number of publications with ‘employee engagement’ and ‘work engagement’ in the title 2000–11 |

Source: Google Scholar (January 2013)

The emergence of engagement in academia is quite well documented, as is shown in Figure 1.1 that summarizes the number of publications on engagement through the years.

Between 2000 and 2010 there was a sharp, yearly increase in the number of publications and, to date (January 2013), around 1,600 papers have been published with ‘work engagement’ or ‘employee engagement’ in the title. In fact, the first scholarly article on engagement at work was published by William Kahn as early as 1990 in the Academy of Management Journal, but it took another decade before the topic was picked up by others in academia. Why was that so? Of course, this has to do with the changes in the world of work that were discussed above and which took place gradually from the late 1990’s onwards. But there is more. At the turn of the century the so-called positive psychology movement emerged. Or rather the science of positive psychology was proclaimed by a group of scholars working with Martin Seligman, at that time the President of the American Psychological Association.

Broadly speaking, as discussed in Chapter 2, positive psychology refers to the scientific study of optimal human functioning that aims to discover and promote the factors that allow individuals, organizations, and communities to thrive. Clearly, work engagement fits into this novel approach that has gained significant momentum in the past decade. So, the positive psychology movement created the fertile soil that made engagement research blossom in academia.

In conclusion, the emergence of engagement at the beginning of the 21st century has to do with two converging developments: (1) the growing importance of human capital and psychological involvement of employees in business, and (2) the increased scientific interest in positive psychological states.

Definitions of engagement in business and in academia

Engagement has been criticized for being no more than old wine in new bottles (Jeung, 2011). Consultancy firms have conceptualized engagement by combining and relabeling existing notions, such as commitment, satisfaction, involvement, motivation, and extra-role performance. For instance, according to Mercer, ‘Employee engagement – also called “commitment” or “motivation” – refers to a psychological state where employees feel a vested interest in the company’s success and perform to a high standard that may exceed the stated requirements of the job’ (www.mercerHR.com). Another firm, Hewitt, states that:

Engaged employees consistently demonstrate three general behaviors. They: (1) Say – consistently speak positively about the organization to co-workers, potential employees, and customers; (2) Stay – have an intense desire to be a member of the organization despite opportunities to work elsewhere; (3) Strive – exert extra time, effort, and initiative to contribute to business success.

(www.hewittassociates.com)

Finally, for Towers Perrin engagement reflects employees’ ‘personal satisfaction and a sense of inspiration and affirmation they get from work and being a part of the organization’ (www.towersperrin.com).

Taken together, these three examples suggest that in business, engagement is defined as a blend of three existing concepts (1) job satisfaction; (2) commitment to the organization; and (3) extra-role behavior, i.e. discretionary effort to go beyond the job description. Additionally, the approaches of consultancy firms are proprietary and thus not subject to external peer review, which is problematic as far as transparency is concerned. For instance, questionnaire items and technical details of measurement tools are not publicly available. This is discussed further in Chapter 15.

Recently, Shuck (2011) searched all relevant HRM, psychology, and management databases and systematically reviewed academic definitions of engagement. Based on 213 eligible publications he identified four approaches to defining engagement:

The Needs-Satisfying approach. Kahn (1990) defined personal engagement as the ‘harnessing of organization members’ selves to their work roles: in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, emotionally, and mentally during role performances’ (p. 694). He conceptualized engagement as the employment and expression of one’s preferred self in task behaviors. Although important for the theoretical thinking about engagement, the Needs-Satisfying approach has only occasionally been used in empirical research (e.g. May, Gilson and Harter, 2004).

The Burnout-Antithesis approach. Rooted in occupational health psychology, this approach views work engagement as the positive antithesis of burnout. As a matter of fact, two schools of thought exist on this issue. According to Maslach and Leiter (1997) engagement and burnout are the positive and negative endpoints of a single continuum. More specifically, engagement is characterized by energy, involvement and efficacy, which are considered the direct opposites of the three burnout dimensions exhaustion, cynicism and lack of accomplishment, respectively. By implication that means that persons who are high on engagement are inevitably low on burnout, and vice versa. The second, alternative view considers work engagement as a distinct concept that is negatively related to burnout. Work engagement, in this view, is defined as a concept in its own right: ‘a positive, fulfilling, work related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption’ (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, and Bakker, 2002: 74), whereby vigor refers to high levels of energy and mental resilience while working, the willingness to invest effort in one’s work, and persistence even in the face of difficulties; dedication refers to being strongly involved in one’s work, and experiencing a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and challenge; and absorption refers to being fully concentrated and happily engrossed in one’s work, whereby time passes quickly and one has difficulties with detaching oneself from work. To date, most academic research on engagement uses the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES), a brief, valid and reliable questionnaire that is based on the definition of work engagement as a combination of vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli, 2012).

The Satisfaction-Engagement approach. According to the Gallup Organization: ‘The term employee engagement refers to an individual’s involvement and satisfaction with as well as enthusiasm for work’ (Harter, Schmidt and Hayes, 2002: 269). Thus, like the definitions of other consultancy firms, Gallup’s engagement concept seems to overlap with well-known traditional constructs such as job involvement and job satisfaction. This is illustrated by the fact that, after controlling for measurement error, Gallup’s Q12 correlates almost perfectly (r = .91) with a single item that taps job satisfaction, meaning that both are virtually identical. The authors acknowledge this overlap by stating that the Q12 assesses ‘antecedents to positive affective constructs such as job satisfaction’ (Harter et al., 2002: 209). Hence, rather than the experience of engagement in terms of involvement, satisfaction and enthusiasm, the Q12 measures the antecedents of engagement in terms of perceived job resources. The reason for that is that the Q12 has been explicitly designed from an ‘actionability standpoint’ and not from a scholarly perspective (Buckingham and Coffman, 1999). In other words, the Q12 was first and foremost designed as tool for management to improve jobs so that employees would be more satisfied. Nevertheless, the Satisfaction-Engagement approach has had a significant impact in academia as well, because Gallup’s research has established meaningful links between employee engagement and business unit outcomes, such as customer satisfaction, profit, productivity, and turnover (Harter et al., 2002).

The Multidimensional approach. Saks (2006) defined employee engagement as ‘a distinct and unique construct consisting of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components that are associated with individual role performance’ (p. 602). This definition is quite similar to that of Kahn (1990) because it also focuses on role performance at work. The innovative aspect is that Saks (2006) distinguishes between ‘job engagement’ (performing the work role) and ‘organizational engagement’ (performing the role as a member of the organization). Although both are moderately related (r = .62), they seem to have different antecedents and consequences. Despite its intuitive appeal, the multidimensional approach (i.e. the distinction between job and organizational engagement) has hardly been taken up by the research community.

Taken together, these four approaches each stress a different aspect of engagement: (1) its relation with role performance; (2) its positive nature in terms of employee well-being as opposed to burnout; (3) its relation with resourceful jobs; and (4) its relation with the job as well as with the organization.

Probably the most important issue in defining engagement is ‘where to draw the line’. Or put differently, what elements to include and what elements to exclude from the definition of engagement. In their seminal overview Macey and Schneider (2008) proposed an exhaustive synthesis of all elements that have been employed to define engag...