The Im/possibility of Existential Therapy

In an approach that is already overflowing with paradoxes, here is yet another – currently, the living therapist and author most often associated with contemporary existential therapy and recognised by professionals and public alike as the leading voice in the field is the American psychiatrist, Irvin Yalom. For example, in a recent survey, over 1,300 existential therapists were asked to name the practitioner who had most influenced them. Yalom ranked second on that list (following Viktor Frankl (1905–1997), the founder of Logotherapy) and was at the top of their list of living practitioners (Correia, Cooper & Berdondini (2014); Iacovou, 2013). Nevertheless, Yalom has stated that there is no such thing as existential therapy per se (Yalom, 2007). Instead, he has argued that therapies can be distinguished by the degree to which they are willing and able to address various existence themes, or ultimate concerns, such as death, freedom, meaning and isolation, within the therapeutic encounter (Cooper, 2003; Yalom, 1980, 1989). From this Yalomian perspective, any approach to therapy that is informed by these thematic existence concerns and addresses them directly in its practice would be an existential therapy.

As an existential therapist, I continue to admire Yalom’s contributions and to learn from his writings and seminars. It has been my honour to have engaged in a joint seminar with him during which we each presented some of our ideas and perspectives (Yalom & Spinelli, 2007). Nonetheless, as the title of this text makes plain, unlike Yalom I see existential therapy as a distinct approach that has its own specific ‘take’ on the issues that remain central to therapy as a whole. Further, as I understand it, existential therapy’s stance toward such issues provides the means for a series of significant challenges that are critical of contemporary therapy and its aims as they are predominantly understood and practised (Spinelli, 2005, 2007, 2008).

Viewing both perspectives, holding them in relation to one another, an interesting and helpful clarification emerges – an important distinction can be made between therapies that address thematic existence concerns and a particular approach to therapy that is labelled as existential therapy.

Like me, the great majority of writers, researchers and practitioners who identify themselves as existential therapists would disagree with Yalom’s contention that there cannot be a distinctive existential model or approach to therapy. Nonetheless, as I see it, they would also tend to be in complete agreement with him in that they, too, place a central focus on the various thematic existence concerns such as death and death anxiety, meaning and meaninglessness, freedom and choice as the primary means to identify existential therapy and distinguish it from other models. As was argued in the Introduction, in my view they are making a fundamental error in this because, as Yalom correctly argues, these various thematic existence concerns also can be identified with numerous – perhaps all – therapeutic approaches. For example, a wide variety of models other than existential therapy address issues centred upon the role and significance of meaning, as well as the impact of its loss, its lack and its revisions (Siegelman, 1993; Wong, 2012). Similarly, the notion of death anxiety is as much a thematic undercurrent of psychoanalytic models as it is of existential therapy (Gay, 1988).

A further problem also presents itself – if only thematic existence concerns are highlighted as defining elements of existential therapy then it becomes possible to argue (however absurdly) that any philosopher, psychologist, scientist or spiritual leader who has ever made statements regarding some aspect of human existence can be justifiably designated as ‘an existential author/thinker/practitioner’. In similar ‘nothing but’ fashion, from this same thematic perspective, any number of therapeutic models can make claims to being ‘existential’, just as existential therapy can argue that, at heart, all models of therapy are, ultimately, existential. While there may well be some dubious value in pursuing such arguments, nonetheless they impede all attempts to draw out just what may be distinctive about existential therapy.

In my view, it is necessary to step beyond – or beneath – thematic existence concerns themselves and instead highlight the existential ‘grounding’ or foundational Principles from which they are being addressed. In doing so, a great deal of the difficulty in clarifying both what existential therapy is, and what makes it discrete as an approach, is alleviated.

I believe that very few existential therapists have confronted the significance of these two differing perspectives. As suggested in the Introduction to this text, one therapist who has done so is Paul Colaizzi. In his paper entitled ‘Psychotherapy and existential therapy’ (Colaizzi, 2002), Colaizzi highlights what he saw as the fundamental difference between existential therapy and all other psychotherapies, that is, whereas psychotherapy models confront, deal with and seek to rectify the problems of living, existential therapy concerns itself with the issues of existence that underpin the problems of living. In order to clarify this distinction, Colaizzi employs the example of a bridge. He argues that if we were to identify all of the material elements that go into the creation of the bridge, none of them can rightly be claimed to be the bridge. The material elements are necessary for the bridge to exist, but no material permitting the construction of the bridge is itself ‘bridge-like’. For the bridge to exist requires a ‘boundary spanning’ from the material elements to the existential possibility that permits ‘the bridgeness of the bridge’. In similar fashion,

For Colaizzi, psychotherapy concerns, and limits, itself with life issues which he sees as being the equivalent of the material elements that are necessary for bridges to exist. Existential therapy, on the other hand, should be more concerned with the ‘boundary spanning’ or ‘stretching’ of life issues so that it is ‘the lifeness of life issues’ (just as ‘the bridgeness of the bridge’) that becomes its primary focus.

Colaizzi’s argument is often poetically elusive. However, I believe the issues he addresses are central to the understanding of existential therapy. Although I am not always in agreement with some specific aspects of his discussion, I think that Colaizzi is correct in pointing out that existential therapists have tended to over-emphasise the thematic concerns that make up the ‘materials’ of existence. If, instead, we were to take up his challenge and focus more on what may be ‘the existentialness of existential therapy’, what might we discover?

What are Key Defining Principles?

Most models of therapy are able to embrace competing interpretations dealing with any and every aspect of theory and practice. Regardless of how different these may be, they remain ‘housed’ within a shared model. What allows this to be so? All models and approaches contain shared foundational Principles, what existential phenomenologists might refer to as ‘universal structures’ that underpin all the variant perspectives within a model, thereby identifying it and distinguishing it from any other. Both psychoanalysis and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), for example, are each made identifiable and distinctive through such foundational Principles. For instance, the assumption of a separate and discrete mental processing system – the unconscious – in contrast to that of conscious processing – is a foundational principle to be found in all variants of psychoanalytic thought. In the same way, the foundational Principles of transference and counter-transference run through all modes of psychoanalytic practice (Ellenberger, 1970; Smith, 1991). Similarly, within CBT, which consists of a huge diversity of views and, at times, quite starkly contrasting emphases, there also exists at least one key underlying principle that runs across, and to this extent unifies, its various strands – their shared allegiance to, and reliance upon, formal experimental design as the critical means to both verify and amend clinical hypotheses (Salkovskis, 2002).

As important as they are in providing the means by which both to identify a model and to reveal its uniqueness, it is surprising to discover that these foundational Principles are rarely made explicit by the majority of practising therapists. This seems somewhat odd since it is through such Principles that the uniqueness of any specific model is revealed. Whatever this might say about the state of contemporary therapy, what is important to the present discussion is the acknowledgement that if an agreed-upon set of foundational Principles for existential therapy can be discerned, then it becomes more possible to clarify what unites its various and diverse interpretations.

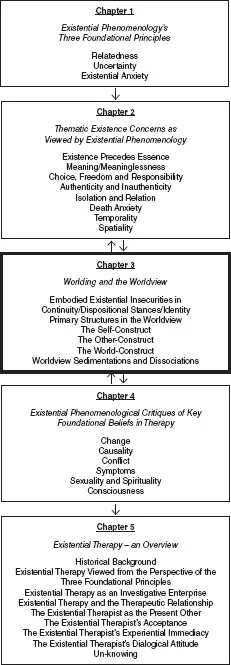

When considering existential therapy, it is difficult not to conclude that there are as many unique expressions of existential therapy as there are unique beings who engage in and practise it. Thus, it is something of a challenge to claim, much less provide evidence for, the existence of shared underlying Principles in the practice of existential therapy – unless one were to argue that the one governing Principle was that of rejecting any foundational Principles. Avoiding that conclusion, this book argues that existential therapy rests upon three key foundational Principles. I will discuss these below and in Part Two I will provide a structural model for practising existential therapy that I believe remains true to these Principles.

Implicit in this enterprise lies a desire to challenge existential therapists to consider critically whether their ways of ‘doing’ existential therapy might be taking on board attitudes, assumptions and behavioural stances that originate from other models but which might not ‘fit’ all that well, if at all, with the aims and aspirations of existential therapy. For example, when considering issues such as therapist disclosures and anonymity might existential therapists be unnecessarily adopting stances that are indistinguishable from those assumed by other approaches? Perhaps, with reflection, the decision to do so might well turn out to be both sensible and appropriate. But it may also be possible that, much like Medard Boss’ daseinsanalysis, which maintains the basic structural stance of psychoanalysis but ‘situates’ this within a distinctly different, even contradictory, theoretical system (Boss, 1963, 1979), existential therapists have assumed attitudes, stances and structures borrowed from other traditions and considered them as required for the practice of therapy without sufficient questioning of these assumptions. Again, in Part Two, I have provided a structural model for practising existential therapy that acknowledges and utilises various contributions from other models while at the same time avoiding being unnecessarily burdened by the structural stances, assumptions and practices derived from them that are inconsistent with its foundational Principles.

Obviously, no enterprise that attempts to respond to these challenges should either dismiss or deny current standards and ethics of practice as delineated by Governing Bodies for the profession of therapy. If it wishes to be acknowledged and approved by these Bodies, any model of existential therapy must remain situated within the facticity of their professional rules and regulations. As such, there is nothing considered or discussed in this text that does not adhere to currently existing standards of practice as presented by the major UK and international Professional Bodies. Nonetheless, at its broadest level, the model under discussion seeks to bring back to contemporary notions of therapy a stance that re-emphasises a crucial aspect that is contained within the original meaning of therapeia – namely, the enterprise of ‘attending to’ another via the attempt to stand beside, or with, that other as he or she is being and acts in or upon the world (Evans, 1981). Although I believe this notion to be a broadly shared enterprise of all existential therapists, why they should take this stance is best clarified when linked to the foundational Principles of the approach.

Which leads to the obvious question: Just what are existential therapy’s foundational Principles?

Existential Therapy’s Three Foundational Principles

Existential phenomenology, as a unique system of philosophically attuned investigation, arose in the early years of the twentieth century. Although it is composed of many interpretative strands and emphases, at its heart is the attempt to grapple with the dilemma of dualism. Dualism has multiple manifestations: the distinctiveness of mind and matter – or lack of it – has been the source of centuries-spanning ongoing debates between idealists and materialists. Such debates, in turn, have confronted issues centred upon everything from the nature of reality in general, to the (assumed) dichotomy between consciousness and the brain, self and other, intellect and emotion, good and evil, male and female and so forth. From the standpoint of structured investigation, which is the hallmark of Western science, dualistic debates have focused on the interplay between the ‘subject’ (the observer/investigator) and the ‘object’ (the observed/the focus of investigation) and whether claims made regarding truly objective data entirely detached from the investigator’s influence are valid and reliable.

Yet another, somewhat different, aspect of dualism can be seen in contemporary theories of physics wherein two mutually exclusive mechanisms are equally required for the most adequate understanding of a particular principle. Theories addressing the wave–particle duality of matter would be an example of this (Selleri, 2013). It is important to recognise that this second expression of dualism differs significantly from the others in that it does not adopt the more prevalent ‘either/or’ stance that separates the contradictory categories under focus. Instead, the contradictory categories are viewed from a ‘both/and’ stance of necessary complementary co-existence.

This ‘both/and’ perspective is uncommon in Western thought. We prefer our dualities to be mutually exclusive and separate rather than complementary and often paradoxical. Our language is so significantly geared toward this preference that, when seeking to express a ‘both/and’ stance, it exacerbates the dilemma by imposing the terminology of contradiction/separatism upon that of complementarity/paradox. For example, other than via mathematics, it seems to be impossible to express the complementary/paradoxical view ...