![]()

Part I

Background

Between them Sennacherib and his hosts had gone forth in all their might and glory to the conquest of distant lands, and had returned rich with spoil and captives, amongst whom may have been the handmaidens and wealth of Israel. . . . Through them, too, the Assyrian monarch had entered his capital in shame, after his last and fatal defeat.

— Austen Henry Layard (1853, 212) on the human-headed bulls that guarded Assyrian King Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh.

![]()

1 The Study of Civilization

Figure 1.0 Assyrian King Assurbanipal (668–627 B.C.) hunting lions, a scene depicted on his palace wall at Nineveh, Iraq. (DEA / G. Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images)

The chariot rattles over the plains as the driver clutches the reins, steadying the horses so the king can take better aim. Bowstring pulled taut, Assurbanipal, supreme ruler of the mighty Assyrian empire, stands ready to fire a volley of arrows against the fleeing lions. Already he has had good sport in the royal park, killing or wounding several of them in a show of kingly skill. Suddenly king and driver hear a roar behind them. An injured lion breaks cover and charges the chariot, seeking to kill its tormentors, but the royal attendants are too quick. Stationed on the back of the chariot for just such an emergency, they thrust their long-handled spears into the lion’s chest. The great beast falls dead in the dust. . . .

Chapter Outline

| What is a "Civilization"? |

| Comparing Civilizations |

| Civilizations and their Neighbors |

| "Primary" and "Secondary" Civilizations |

| The Rediscovery of Ancient Civilizations |

| Classical Civilizations: Greece and Rome |

| Egypt |

| Mesopotamian Civilizations: Assyrians and Simierians |

| Greece and Crete: Minoans and Mycenaeans |

| The Indus and Eastern Asia |

| The Americas: Mesoamerica |

| The Americas: Peru |

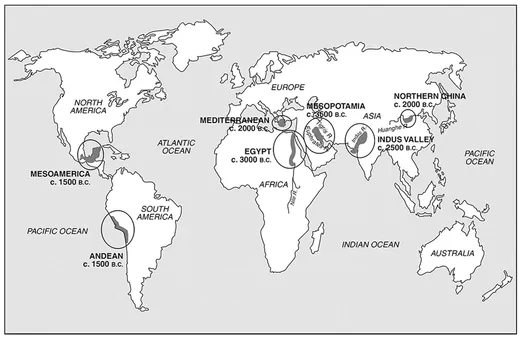

Figure 1.1 The distribution of early pre-industrial civilizations.

The modern visitor can see the scene of King Assurbanipal’s lion hunt, carved in stone, in the Assyrian gallery of the British Museum. It is one of the many monuments of “civilization” that fill great Western museums, be it the Louvre in Paris or the Metropolitan in New York. Wander into adjacent galleries and you will find mummiform coffins from ancient Egypt and intricate bronze ritual vessels from early China. Just around the corner will be red-figured vases from classical Athens or marble busts of Roman emperors. Many enthusiastic and intrepid tourists venture further afield and visit the places from which these priceless relics originated. They wonder at the sheer size of the pyramids in Egypt or at the desolation that now surrounds many of the ancient cities of Mesopotamia. They sail the Aegean, tracing the routes taken by ancient Greek mariners 2,500 years ago. Or they wander over the Maya ball courts of lowland Mexico, pondering just how the game was played, or climb the steep hill to the “lost” Inka city of Machu Picchu in Peru.

All these are remains of what today we call “ancient civilizations” (see Figure 1.1; Table 1.1). Their study has attracted both archaeologists and the general public since at least the rebirth of Western learning in the sixteenth century. Ancient Civilizations describes these extraordinary early societies, using archaeological evidence and historical records, oral traditions, and scientific evidence from many academic disciplines. Thus, our story comes not only from modern science but from the voices of those who created the early civilizations as well.

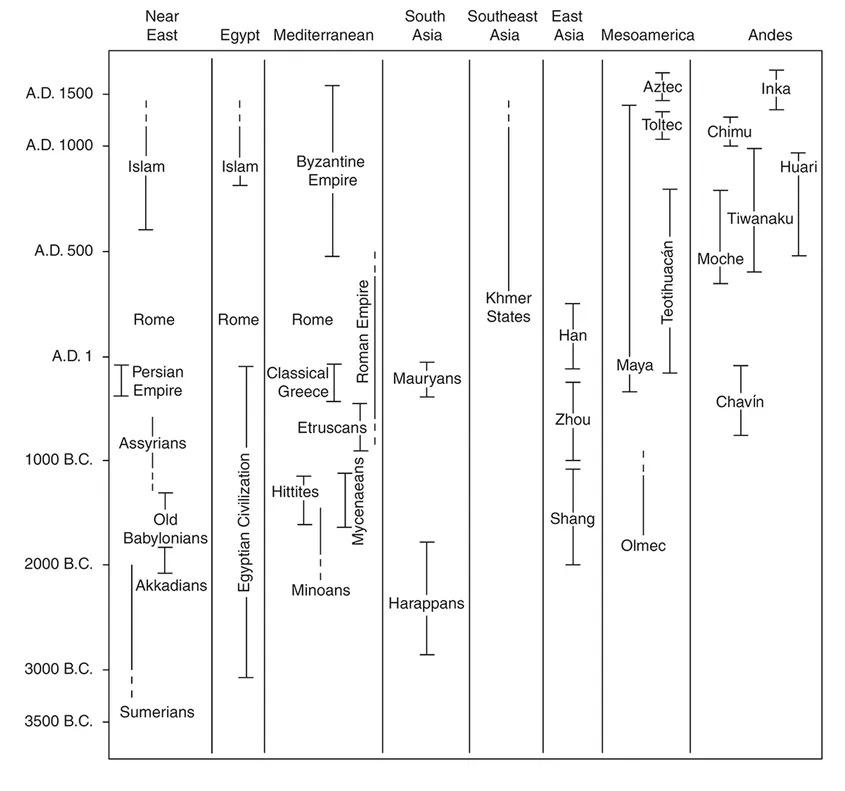

In space and time, the societies we will describe span five thousand years and cover most regions of the world: from the first cities of the ancient Near East, around 3500 B.C.; through Egypt and China, classical Greece and Rome; to the New World civilizations of the Maya and Olmec; ending with the Aztec and Inka empires, which were flourishing at the time of the Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century A.D.

What is a "Civilization"?

Table 1.1 Chronological Table of the World’s Earliest Civilizations

The proper definition of civilization has occupied the minds of archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians for generations. An enormous scholarly literature surrounds this complex subject, but for the purposes of this volume we must content ourselves with a simple, if possible all-embracing, working definition that covers a great multitude of complex, early civilizations.

According to that ultimate arbiter of the English language, the Oxford English Dictionary, “to civilize” is “to bring out of a state of barbarism, to instruct in the arts of life; to enlighten and refine.” The notion that “civilization” is a condition superior to “barbarism” underlay Victorian doctrines of racial superiority of more than a century ago and lives on today in the popular understanding of the word. But it has no place in archaeology. Archaeologists do not regard civilizations as better than hunter-gatherer societies or those of small-scale farmers, only different. It is perhaps only natural to admire the grandiose monuments, the powerful artworks, and the evocative literature left by the ancient Romans or Egyptians. These give us a vivid picture of complex societies, in some senses comparable to our own. But they are not “better” than earlier or contemporary less complex societies.

Politically minded commentators might well draw the opposite conclusion: that the ancient civilizations, with their privileged elites and centralized governments, were worse places to live for the ordinary peasants or the urban populace. There is certainly ample evidence of the cruelty that so-called civilized societies could inflict on their enemies, or even on their own subjects, through warfare, slavery, coercion, and punishment. Even in classical Athens, home of the philosophers Socrates and Plato, there were probably as many slaves condemned to working the lead and silver mines as there were male Athenians who were citizens. Furthermore, many of the artworks we so much admire today were produced for an elite and were seen by only a privileged few. Yet the achievements of the early civilizations are undeniable, and we must not underestimate their significance to world history.

It was really only in the twentieth century, and particularly during the past half century, that archaeologists finally abandoned the idea of civilization as a condition superior to other types of human society. A hundred years ago, the climate of scholarly opinion was very different. Nineteenth-century archaeologists and anthropologists were heavily influenced by theories of biological and social evolution developed by the biologist Charles Darwin and the social scientist Herbert Spencer. In his Origin of Species, published in 1859, Darwin had shown that in the natural world, it was only the fittest plants and animals that survived and that “natural selection” was the guiding force in making others extinct. Early social scientists such as Spencer attempted to apply the same reasoning to human societies. They saw well enough that urban literate societies (civilizations) were replacing less-complex societies throughout the world, and they considered this to be proof that civilizations were in an evolutionary sense “superior.” French archaeologist Gabriel de Mortillet summarized this thinking and the achievements of nineteenth-century archaeologists in a guidebook to the archaeology exhibits at the Paris Exposition of 1867. He wrote of laws of human progress and similar human development. De Mortillet also assumed that humankind was very ancient.

English anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor was one of the fathers of Victorian anthropology and a fervent believer in human progress. He surveyed human development in all of its forms, from crude Stone Age axes found in France to Maya temples in Central America and finally to Victorian civilization. Tylor reemphasized a three-level sequence of human development popular with eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century scholars: from simple hunting “savagery” through a stage of simple farming to “barbarism,” and then to “civilization,” the most complex of human conditions. Tylor’s contemporary, American anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan, went even further. In his Ancient Society (1877) he proposed no fewer than seven distinct periods of human progress, starting with simple savagery and culminating in a “state of civilization.”

Such doctrines of unilinear (single-line) cultural evolution remained popular well into the twentieth century. In the 1930s and 1940s, Australian-born archaeologist V. Gordon Childe refined this general approach in What Happened in History (1942). He equated “savagery” with the hunter-gatherers of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, “barbarism” with the farmers of the Neolithic and Copper Age, and “civilization” with the Bronze Age communities of the Near East. As “barbarism” was superior to “savagery,” so was “civilization” to “barbarism.” Childe believed that progression from one condition to the next needed little explanation, only the opportunity to be presented for societies to make the change. These emotive terms are no longer acceptable in modern archaeological thinking.

Today, archaeologists use the term civilization as a shorthand for urbanized, state-level societies. These are sometimes called “preindustrial civilizations” because they relied on manual labor rather than fossil fuels such as coal. Not everybody accepts the definition in such simple terms. Some scholars have even drawn up long lists of features that they feel societies must possess to qualify as civilizations. Such lists often include writing and metallurgy. The limitations of this approach are obvious. For example, the Inka of the Andes did not use writing, yet they had centralized government, substantial cities, an ordered and hierarchical society, specialized craft skills, metallurgy, and an elaborate network of roads and rest houses, as well as a record-keeping system involving knotted strings. Few would deny them the status of a civilization.

How, then, do archaeologists recognize and define a civilization? This is a difficult area of discussion. We have already referred to two of the primary characteristics: urbanization (the presence of cities) and the state (a centralized political unit). These features in turn need to be defined:

- A city is a large and relatively dense settlement, with a population numbered in at least the thousands. Small cities of the ancient world had 2,000 or 3,000 inhabitants; the largest, such as Rome or Changan (China), may have had over a million.

- Cities are also characterized by specialization and by interdependence between the city and its rural hinterland and between specialist craftspeople and other groups within the city. The city is what is termed a “central place” in its region, providing services for the villages of the surrounding area while at the same time depending on those villages for food. Most cities, for example, would have had a marketplace where agricultural produce could be exchanged.

- Cities also have a degree of organizational complexity well beyond that of small farming communities. There are centralized institutions to regulate internal affairs and ensure security. These usually find expression in monumental architecture such as temples or palaces or sometimes a city wall. Here we must recognize an overlap between the concept of the city and the concept of the state. States, too, are characterized by centralized institutions. It may be possible to have states without cities; but it is hard to envisage a city that is not embedded within a state .

An ancient city site will usually be obvious to archaeologists, both from its size and from the scale of its remains. The state is more difficult to define. It is essentially a political unit, governed by a central authority whose power crosscuts bonds of kinship. Kin groups do not disappear, of course, but their power is reduced, and a new axis of control emerges that is based on allegiance to a ruling elite.

Cities and states are not the only factors that have been cited in historical attempts to define civilization. One of the most famous attempts was made by V. Gordon Childe, whom we have already mentioned. In 1950, he drew up a list of traits that he considered to be the common characteristics of early civilizations throughout the world. In the 1970s, archaeologist Charles Redman divided Childe’s list into “primary” and “secondary.” The primary characteristics include cities and states, together with full-time specialization of labor, concentration of surplus, and a class-structured society. The five secondary characteristics are symptoms or by-products of these major economic and organizational changes: monumental public works, long-distance trade, standardized monumental artworks, writing, and the sciences (arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy).

We have already noted the shortcomings of such lists of shared traits. Whether they can ever be considered an adequate “definition” of a civilization is open to question. Furthermore, as we have seen, not all civilizations possess all of Childe’s ten traits, although they nonetheless provide a handy checklist of items we might expect to find.

This is a book about preindustrial civilizations drawn on a very wide canvas. Many surveys of early civilization confine themselves to the first states and to the controversies surrounding the origins of civilization, one of the great issues in archaeology. We have chosen instead to describe early civilizations on a global basis and their development over long periods of time. For instance, in the Near East, we cover not only the first city-states but also the empires of Assyria and Babylon. In the Mediterranean region, where many surveys of early civilization stop with the fall of Late Bronze Age Mycenae in about 1200 B.C., we have included chapters on the Greeks, Carthaginians, Etruscans, and Romans. In East Asia, coverage of the earliest Chinese civilization, that of the Shang, is followed through in a later chapter on the Han empire, where the emergence of states in Korea and Japan is also outlined. Similarly, in the Americas, we cover the entire 3,500-year trajectory of state-organized societies in Central and South America.

Comparing Civilizations

The world’s early civilizations developed along many different lines while at the same time sharing some fundamental core features, such as social complexity, that define them as civilizations. Cities are characteristic of both Sumerian and Mayan civilizations on different sides of the world. The Egyptians buried their monarchs under pyramids; so did the Maya. Social inequality is common to all early civilizations, as is a strongly centralized government headed by a minority who controlled all valuable resources and the loyalty and labor of thousands of commoners. Force, or the threat of force, was all-important as a means of coercing rivals and rebellious citizens. The Egyptians, the Khmer of Cambodia, and the Aztecs of Mexico all had forms of divine kingship, but vary in many other respects. Comparison is helpful at a different level, however, one that does not seek to establish grand theories but merely to describe or review similarities and differences. This was the approach taken by Canadian archaeologist Bruce Trigger, who compared seven early civilizations in such features as population density, technology, religious beliefs and practices, legal systems, and family and community organization.

Trigger emphasized an important distinction between civilizations based on city-states (such as those of Mesopotamia, the Maya, or Greece) and those (such as Egypt, the Inka, and Shang China) that were unitary or territorial states. He pointed out that in city-states the city’s populace made up the whole spectrum of society, with craftspeople, farmers, and the elite. The cities themselves were hubs of commercial activity, with flourishing markets. By contrast, in territorial states the earliest cities were principally political centers. Farmers lived in the rural hinterland in small settlements, secure without walls (since territorial states were less afflicted by internecine strife). Trigger argued that in territorial states the interaction between rural farmers and urban centers was largely in the form of taxes paid by the farmers to the city-based bureaucracies. The farmers were less reliant on urban craftspeople and markets than they were in city-state societies.

The nature of the early cities themselves was very variable. Some were dense concentrations of population, bounded by a city wall for defense. Others were ceremonial and administrative centers, surrounded by more diffuse populations that supported the needs of the elites and those resident in the urban core. This “low density urbanism” was a feature of civilizations in tropical latitudes, such as the Maya and the Khmer whose vast complex at Angkor spread over many square kilometers. Even in walled cities, however, we should not...