The historical context is important for understanding British society, whether for Britons or for overseas observers. However, searches for historical ‘truth’ inevitably involve contested interpretations or ignorance of the presumed facts. Polls regularly suggest that many British respondents often lack an adequate knowledge of Britain’s past, current conditions and institutional structures.

International respondents’ replies to polls may also reveal stereotypical perceptions about Britain and its people. They tend to see the British as either fair-minded, outward-looking and tolerant or, conversely, as close-minded, insular, conventional and backward-looking with an exaggerated respect for their history and traditions. The country is sometimes perceived through images of monarchy, castles, aristocracy, quaint and eccentric behaviour, class conflict, a stagnating, risk-averse economy, unimaginative food and dysfunctional old- fashioned institutions. Such views arguably do not accurately convey the complex and diverse reality of Britain, with its problems, strengths and weaknesses.

For example, historical confusion was shown in replies by both British and overseas respondents to a British Council survey in February 2014 at a time when the centenary anniversary of the 1914–18 First World War was being commemorated as a significant event in British and world history. Only 38 per cent of British respondents knew that US and Canadian troops fought in the War and 35 per cent were aware that Australian and New Zealand Commonwealth troops also took part. There was ignorance about which side (Allied or German) some countries fought on, with 27 per cent of Indian respondents thinking that India fought against Britain, despite 1.4 million Indians serving in the British forces. The survey noted how the War still provokes positive and negative overseas attitudes to the UK and revealed how many British often tend to view their wartime experiences in terms of patriotism and sacrifice.

British state schools have recently been criticized for their teaching of history by restricting study to limited periods and subjects, such as the Tudors or Nazism. In an attempt to correct an alleged lack of historical knowledge, reforms have been made to the state school National Curriculum, so that history is now intended to be a more fact-based and chronological subject. Courses on citizenship have also been introduced in the hope that pupils will learn what constitutes British civic culture. These efforts at consciousness raising may not always be successful, but politicians argue that such reforms of the school curriculum do valuably promote debate on national identity, and improve pupils’ knowledge.

Historical growth

Britain’s constitutional title is the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK). The nation comprises large and smaller islands off the north-western European mainland, which are touched by the North Sea, the English Channel, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The biggest island, Great Britain, is divided into England, Scotland and Wales, and Northern Ireland shares the second-largest island with the Republic of Ireland, with which it has a land border. This border remains a crucial and divisive element in the UK’s attempt to leave the European Union (EU).

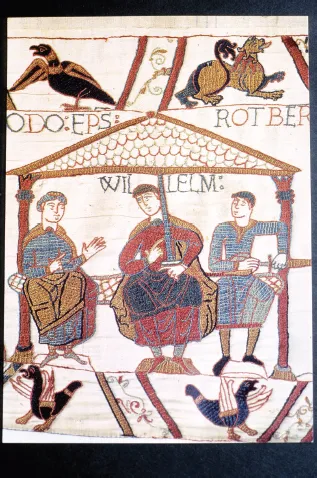

Plate 1.1 Representation of William the Conqueror (centre with his half-brothers) on the Bayeux Tapestry; a 70 m embroidered cloth made in England in the 1070s (now in Bayeux Abbey, France), depicting events leading to the Norman Conquest of England, 1066. © Hemis/Alamy Stock Photo

In prehistory, these areas were visited by Old, Middle and New Stone Age nomads (Palaeolithic), some of whom stayed permanently. From about 600 bc–ad 1066, the islands experienced settlement and invasion movements from people who originated in mainland Europe, such as Celtic groups, Belgic tribes, Romans, Germanic tribes (Anglo-Saxons), Scandinavians (Vikings) and Normans. The Norman Conquest by William the Conqueror was a defining event, which spread Norman control over much of the islands and fundamentally influenced the country’s social and political structures.

Conventional accounts of British history suggest that descendants of these early immigrants over time collectively created the foundations for a multi-ethnic UK with mixed identities and cultures. Various degrees of interbreeding between newcomers and natives produced further, and often contested, identities. Research published in Nature in 2015 (see Further reading) indicated for example that assumed majority Celtic areas were more genetically diverse than has been thought, while other groups (such as Picts and Scots) are thought to have been isolated for centuries.

The settlers and invaders contributed between the ninth and twelfth centuries ad to the building-blocks which gradually established the separate nations of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland (with England and Scotland gaining stronger individual identities by the tenth century). The countries experienced different internal developments and political changes, as well as conflicts with each other and other countries, in their growth to nationhood. There are still differences between these peoples and competing allegiances within and among the four nations.

The later development of the islands was greatly influenced first by the expansionist, military aims of English monarchs and second by political unions. Ireland and Wales had been effectively under English control since the twelfth and thirteenth centuries respectively. In 1603, James VI of Scotland, whose mother was Mary, Queen of Scots, inherited the English throne as James I after the death of Elizabeth I, which dynastically joined Scotland and England. Movement towards a British state (with its parliamentary power base at Westminster in London) was achieved by political unions between England, Wales and Scotland (Great Britain) in 1707 and between Great Britain and Ireland (United Kingdom) in 1801. In 1921, Southern Ireland left the union to become the independent Republic of Ireland while Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom.

These historical developments involved political deals, manipulation, wars, constitutional struggles and religious conflicts, and resulted in the gradual creation of a British state (the UK), which owed much to English models and dominance. State structures, such as the monarchy, government, the Church, Parliament and the law, often developed slowly and unevenly, rather than by long-term planned change and there were also periods of upheaval and ideological conflict (such as royalist and tribal battles, civil wars, nationalist revolts by the Scots, Welsh and Irish against the English, struggles with European powers, religious ferment, the Protestant Reformation and social dissent).

Plate 1.2 James I of England (VI of Scotland) in full state robes. Portrait by Inigo Jones c. 1620, following the dynastic union of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603. © GL Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

It might seem that this British story involves a confused and haphazard history of often unforeseen events, rather than purposeful action. Yet some historians have argued that Britain has developed in a gradualist, evolutionary and pragmatic manner, where common-sense change was accepted if it worked. This process has been attributed to the supposed insular and conservative mentalities of island peoples, with their preference for traditional habits and institutions, orderly progress and distrust of sudden change. Although some influences have come from abroad during the long historical process, the absence of any successful military invasion of the islands since the Norman Conquest of 1066 has allowed England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland to develop internally in distinctive ways, despite frequent and violent struggles between and within them.

The social organizations and constitutional principles of the British state, such as parliamentary democracy, government, the rule of law, economic systems, a welfare state and varied religious faiths, have been slowly and variously forged by disputes, conflict, conquest, self-interest, consensus and compromise. The structures and philosophies of British civic statehood have often been imitated by other countries, or exported abroad through the creation of a global empire from the sixteenth century and a commercial need to build world markets for British goods.

The developed British Empire was an extension of earlier English monarchs’ internal military expansionism within the islands and in mainland Europe. Following later European reversals, they sought raw materials, possessions, trade and power abroad. This colonialism was aided by increasing military strength (achieved by successive victories) into the twentieth century. In Britain today, there is a vigorous debate about colonialism. Some critics see it as a negative, regrettable stain on British and world history, while others controversially feel that it may have some positive features.

Internally, agricultural and farming revolutions in Britain from the New Stone Age and Anglo-Saxon periods added appreciably to the country’s wealth, exports, prestige and international trade. It also developed a manufacturing and financial base, with connections to Europe and beyond. It became an industrial and increasingly urbanized country from the late eighteenth century because of a series of industrial revolutions and inventions. Throughout its history, Britain has been responsible for major and influential scientific, medical and technological advances.

Plate 1.3 Queen Victoria, 1819–1901. Queen of the UK, became Empress of India in 1876; had the longest reign of any British monarch (63 years) until overtaken by Queen Elizabeth 11 (66 years in 2018); photograph by Alexander Bassomo, 1882. © Mary Evans Picture Library

The development of the British state and its empire was aided by increasing economic and military force, so that by the nineteenth century the country had become a dominant industrial and political world power. It was a main player in developing Western civic principles of law, property, business, liberty, capitalism, parliamentary democracy and civil society.

Acts of Union within Britain in 1707 and 1801, despite continuing tensions and allegiances to long-held separate identities, had also gradually encouraged the idea of a British identity (Britishness), in which all the component countries of the eventual United Kingdom could share. This was tied to Britain’s imperial position in the world and an identification with the powerful institutions of the state, such as monarchy, law, Parliament, the military and Protestant religion. But individual identitie...