![]()

1

HASTINGS, SUSSEX

NO JACKBOOTS, PLEASE. WE’RE ENGLISH

THE ENGLISH NEVER KNOW WHEN THEY ARE BEATEN

SPANISH SAYING

‘Listen mate,’ says the Saxon soldier, hitching up his sword belt. ‘Never mind about the result on the battlefield. What counts is inside here.’ And he gives a thump on his chain mail where it covers his heart. ‘Inside here, mate,’ he repeats with a glare, ‘we English win every year.’ He’s not joking.

I’ve just arrived at the spot near the south coast of England where Duke William of Normandy defeated King Harold’s Saxon army at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Today is the anniversary of the battle, and our Saxon soldier is one of several thousand individuals who come here every year on this day, dressed in cross-gartered leggings, hand-stitched leather boots, chain mail, shining helmets and armed with spears, swords and battleaxes, just as their ancestors did 950 years ago. He’s a battle re-enactor. And thousands more of us on this sunny day have turned up to watch them fight it out.

Meanwhile, before the mayhem starts, the mood on the vast field below the walls of Battle Abbey is both festive and feverish. There are kids chasing each other, brandishing brightly coloured plastic weaponry. There are parents yelling at them not to get lost, and come and get a burger, and yes, I mean now! And mingling among those of us in jeans, T-shirts and trainers or similar twenty-first-century kit, adults in medieval dress are trying with self-conscious nonchalance to look as though it’s perfectly normal on a Saturday morning in a field in East Sussex to be dressed like an extra from Lord of the Rings.

This is not just a blokeish pursuit. I can see around me plenty of female camp followers as well, mostly in long brown frocks made from rough cloth and wearing white pointed hats with silky material swirling around their shoulders. There’s one here now, hanging on the arm of our Saxon soldier.

What I’d said to him – after a pleasant and informative conversation about the handiness of the short-sword hanging from his waist – was, ‘Good luck this afternoon in the battle,’ and I’d added with a stagey wink, ‘You never know, maybe this’ll be your year to beat the Normans.’ Not a side-splitter, I realise, as Saxon jokes go. But his answer is collectable. ‘In here,’ (he taps his heart) ‘we English always win.’ – such a poetic sentiment from a man dressed as an old-time thug. It tells of his pride in his country, a nation somehow able to snatch glory from the humiliation of defeat. So, waiting till he and his damsel have strode on so I won’t offend him further, I pull out a notebook and biro to scribble down a couple of lines about the encounter.

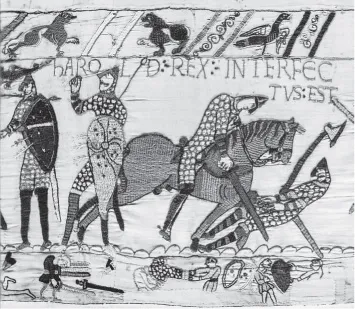

A panel from the Bayeux Tapestry, dating from the 1070s. The idea that Harold was hit in the eye by an arrow is probably a myth, started later by the Normans who wanted to portray his death as God’s judgement on an illegitimate ruler. Then in the eighteenth century, during overenthusiastic restoration of the tapestry, an arrow was added where there may not have been one originally.

I’ve come here today not just for the entertainment. I’m on a quest for first-hand evidence that might help unravel a puzzle. Who, exactly, do the English think they are? Where do they come from? What is it in their history that makes them so … English? And what does being English mean? To find answers, we’re going to travel through time and space. We’ll explore twenty places that have played a role throughout history in forming the national identity of the English. Our journey will take us from an Anglo-Saxon church to a Second World War airbase, from a Northumbrian island to the White Cliffs of Dover, and in between we’ll be visiting a pub, a racecourse, a slum, a mansion, a battleship and many more places, criss-crossing England through 1,600 years. And at the end of our journey, we’ll ask the unthinkable: does the whole idea of English national identity still have meaning in the twenty-first century? Or have European federalism, globalised commerce and mass migration rendered it obsolete?

***

So why have we come first to Hastings? The reason is simple. The battle fought here in 1066 was the most important turning point in English history. Once the Norman duke, William the Conqueror, had triumphed and been crowned King of England, no jackbooted army of occupation ever goose-stepped through the land. In almost a millennium since that battle on the south coast, England has never again been successfully invaded. Napoleon, Hitler and others have tried. None managed it. That doesn’t mean the English have been free from any outside influence for all those centuries – far from it. As we shall see on our journey, many encounters – both peaceful and warring – with others beyond our shores have all helped mould the English character. Nevertheless, the fact that the country has seen off every foreign attempt to seize the country by force for the last nine and a half centuries has had two effects. It has reinforced the sense of an unchallenged English national identity, and it has established the notion (in English minds, at least) that the English are a free and independent people. The English have a political and social history that goes back in an unbroken line further than that of any other race on earth.

Thus, the Battle of Hastings – defeat as it was for the English – has become a symbol of the nation’s independence. And so here we are today on the anniversary of the battle, along with many thousands of our fellow countrymen, for whom Hastings means… well, that’s one of the things we’re here to find out.

***

The re-enactment itself is due to start at 3 p.m., so there’s time to interview a few subjects first. One of the attractions is a medieval market. Apart from half a dozen food stalls, each with a line of hungry visitors, and one tent selling gifts, as well as the sort of armaments with which the small children are bashing each other, the rest of the tented shops cater for the Saxon re-enactor’s yearning for authenticity. Some sell pointed helmets and heavy belts. Some have got smocks, headscarves and medieval shoes for sale. Others advertise eleventh-century cooking equipment. And another has an array of standards and pennants as used by Aethelwold, Eadwig and other pre-Conquest monarchs.

A man in a green smock is hammering away over a glowing forge, pausing occasionally to explain to a small crowd how you make chain mail. A young woman, whom he refers to as ‘Lady Matilda’, is passing among us. Folded across her arms is a complete coat made of little iron rings interlocked like a loose-knit sweater.

‘How heavy is it?’ I ask her.

‘Over 40 pounds,’ she replies.

‘Good heavens!’ I say. ‘I wouldn’t want to be wearing that while I was trying to run away!’

‘You would if they caught you,’ she says with a grin. ‘Here, hold it.’ And she drapes it across my wrists.

‘Bloody Hell!’ I exclaim, staggering for a moment as my arms sag under the weight.

Further on is an axe shop. The salesman is a young guy who, above the usual chain mail, leather and scabbard, sports a thick growth of facial and head hair at odds with the youthful features they frame. I pick up one of the axes. There are a dozen of them hanging on a rail, each with a black blade and a wooden handle as long as your arm.

‘How much?’ I ask.

‘Sixty-five quid,’ he replies.

‘Sixty-five quid!’ I exclaim. ‘Crikey, it’s expensive, this reenacting game.’

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘You can spend hundreds on the right costumes and equipment.’ I raise my eyebrows in a quizzical expression. ‘Everything – weapons, clothing – has got to look authentic. We’d be letting the side down if we turned out with some tatty old plastic sword and a polyester T-shirt.’

I nod. ‘So, when you say “letting the side down”, you mean your fellow re-enactors?’

‘Yes. And the country. England,’ his voice now slightly raised in irritation at my ignorance, and perhaps at my lack of patriotism.

I feel the need to be defensive. Running my finger down the axe-blade, I remark, ‘Not very historically sharp, is it?’

‘Well, we’re not so authentic that we want to actually kill each other,’ he smiles.

‘So how do you avoid people getting hurt in the battles?’

‘We train,’ he says, ‘at weekends. You’re not allowed to take part in a battle till you’ve been on a course.’

‘A course? You mean with professional combat instructors?’

He nods. ‘And,’ he adds, pausing for emphasis, ‘we have a health and safety officer.’

At that moment, a giant thug of a man arrives at my side. He’s tooled up like a Saxon gangster, smoke drifting from his nose, a cigarette cupped in his hand. Even I am not foolish enough to point out to him that he’s infringing the central rule on anachronistic behaviour.

***

It’s time to grab a sandwich and a good place to see the battle. There’s half an hour to go. Most visitors have been cannier than me. They bagged their spots an hour or more ago on the grassy slope above the roped-off part of the field where the big event is going to happen. The spectators are clearing the picnic remains off their blankets and adjusting their collapsible chairs. Kids are managing – as only kids can – to run about, trip over and eat ice creams all at the same time. I’m relegated to a back row, where I need to stand to get a decent view.

Before us, on the other side of the rope barrier, a man in knitted tie and corduroy jacket (the universal uniform of male history teachers) is walking up and down with a microphone, delivering a lesson on the background and origins of the Battle of Hastings. Creditable as this is, no one’s listening. They’re all gossiping or playing about. It’s just a background drone, like the TV on in the corner during the day.

After twenty-five minutes of this, the mood suddenly shifts. A mob of men – at a rough count about a thousand – in pointed helmets, carrying swords and shields, trudge into view on the right-hand side of the field, and the lecturer promptly switches roles to commentator, ups the tempo of his monologue and shouts through his mic, ‘Let’s have a big cheer, ladies and gentlemen, for Harold – and – the – Saxon – ARMY!’ Everyone around me bawls their heads off.

Two tall young men come and stand directly in front of me so I can’t see.

‘Excuse me, guys,’ I say.

The nearer one turns to me, ‘I do apologise, sir. Please forgive us,’ his excessive politeness making me wonder if he’s being sarcastic. But then, as they both move to one side, he continues, ‘We had not realised already that you your view we are blocking.’

‘No problem,’ I say. ‘Where are you from?’

‘Germany,’ he replies. ‘We are both in London University.’

‘Ah, I see. From Saxony, by any chance?’

‘Ahh, a very good joke,’ he replies. ‘But no, we do not live in northern Germany. But my friend here and I are from Bavaria. It is very nice there.’ And he launches into a detailed, if fractured, account of Bavarian Christmas street markets.

Soon, the Saxon soldiers start to chant something with three syllables which is difficult to make out through the description of Alpine Weihnachtsfest infiltrating my left ear. ‘Excuse me a sec.,’ I say to the student, who bows politely, and I make out the words, ‘God-win-son. God-win-son. God-win-son.’

The announcer explains. ‘The Saxon troops are chanting the name of their king, Harold Godwinson.

Then the chant changes to what sounds like, ‘Oot! Oot! Oot!’ (I’ve yet to meet anyone who knows what that means.)

At this point, the enemy arrive, about a thousand foot soldiers clomping in from the far left. They line up 200 yards from the Saxons, then fire off a few arrows that curl high into the air before making a miserable touchdown in no-man’s-land. ‘Let’s give a big hand now, everybody, for – William – and – the – NORMANS!’

Once the crowd has stopped booing, I turn to the student, who’s now busy videoing the whole thing on his phone, and ask, ‘Do you have anything like this in Germany?’

‘Once I was in a restaurant in Bavaria,’ he replies, ‘where two men dressed up like soldiers of Frederick the Great and demonstrated to the customers their swords.’

‘And that’s it?’

‘Yes, that is the only re-enactment I have seen in Germany.’

I look around for more interviewees. A few yards behind me, three men in red tracksuit tops are standing to attention. Each is holding a pole 9 or 10ft tall from which flutters a red flag with a white lion on it. I trot over to talk to them. As I get close, I see written on their chests, ‘English Community Group (Leicester).’

‘Hello there,’ I say, trying to sound as matey as possible. One of them nods, so he’s the one I address. ‘I’m curious about …’ – I pointedly study the words on his jacket – ‘… the English Community Group.’

‘(Leicester),’ he adds.

‘Forgive me, I’ve not heard of it before.’

He relaxes his shoulders and stands easy. ‘We exist to politely represent the interests of the English community in Leicester and Leicestershire,’ he says.

‘Oh,’ I say. ‘“Politely”?’

‘That’s right, we’re not the BNP.’

‘A-ha. I see. So why is the Battle of Hastings importa...