eBook - ePub

Britain, Europe and National Identity

Self and Other in International Relations

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This study patterns national identity over a number of important historical milestones and brings the debates over Europe up-to-date with an analysis of recent happenings including the referendum on Scottish independence, the global economic crisis and the current crisis in Syria.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Britain, Europe and National Identity by J. Gibbins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Theory and Method

The first layer: discourse analysis

The assumptions of discourse analysis

Discourse analysis can be defined as an “approach to the analysis of language that looks at patterns of language across texts as well as the social and cultural contexts in which the texts occur” (Paltridge, 2006, p. 2). These patterns of language mean that discourse is firmly lodged within a view of our world as socially constructed. Discourse analysis, therefore, seeks to argue that an external reality cannot be held as authoritative and universal but is instead a series of representations. The representations have been abundant over the ages with such examples including among others “God, Reason, Humanity, Nature, and the Iron Laws of Capitalism” (Torfing, 2005, p. 13). These categorisations enable our understanding of our ‘reality’, which is contingent on social, cultural and historical contexts.

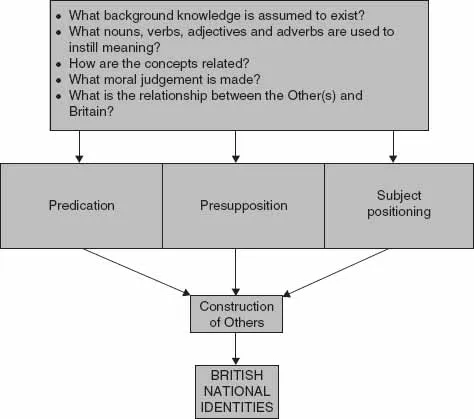

The essence of discourse theory is rooted in the study of both spoken and written language because the language we employ when describing our ‘reality’ gives it meaning. However, how can language reveal discourses that are structurally fixed enough to enable them to be studied while assuming language is inherently volatile? This peculiarity can be explained in two ways. Firstly, Laclau and Mouffe adopt the concept of nodal points, which are “privileged signifiers or reference points … in a discourse that bind together a particular system of meaning or ‘chain of signification’” (Howarth and Stavakakis, 2000, p. 8). Hence, the act of articulation contains the construction of nodal points, which partially fix meaning allowing for a structural reading of language. Secondly, one can adopt a differential rather than a referential approach to language. A referential understanding, according to Wæver, is “where words and concepts are names used in order to make reference to objects out there in reality” (2002, p. 28). He goes on to mention that a referential approach, therefore, “will not have much to work with than the degrees of deviation from the ideal of language as a transparent medium” (2002, p. 28), resulting in a bias towards psychological accounts rooted in “‘perceptions’ or ‘belief systems’ or ‘images’” (2002, p. 29). On the other hand, a differential understanding defines concepts according to their relationship with other similar and different concepts. That is, Milliken makes the claim that discourses function as systems of signification within which meaning occurs via the relationships between objects placed within the sign system (1999, p. 228). The interlinking between subjects and objects can be revealed empirically via the conceptual tools of predication, presupposition and subject positioning. Although expanded on later, these three methods for analysis provide the particular features and attributes of subjects that are referred to, the background that is taken to be true and the manner in which the subjects and objects are linked and related. It is via these three processes that the practice of identity formation can be established.

Why discourse analysis?

As already mentioned, discourse analysis functions as an empirical tool for scrutinising what is said, written or communicated, and, no less importantly, what may not be said, written or communicated. A discursive approach, because it posits that language is inherently unstable, offers an insight into how norms, values and identities are subject to change. Rationalist methodologies have frequently argued that norms, values and identities are fixed and given, and interests, therefore, need not be bogged down by their consideration. Discursive and constructivist approaches, however, have been at pains to deny the exogeneity of these phenomena, which, in turn, allows for a study of the catalysts that construct and reconstruct them. As this study focuses on the inherent multidimensionality of identity, a constructivist/discursive approach is employed over a more methodologically narrowing rationalist one.

Furthermore, a discursive position illuminates power structures that are implicit in the social and political world. Indeed, instead of power being perceived as the possession of material resources or capacity, it operates according to patterns of inclusion and exclusion. Instead of taking interests as realised through power as given, the approach I adopt contends that interests are actually constructed and illuminated through patterns of language, or discourses. Power structures, be they evident or hidden, permeate the political arena and set certain privileged agendas. Hence, a discursive approach helps expose and critique that which is often accepted as commonsense or somehow ‘natural’ to the political and social world. As such, it brings to light new or previously hidden vistas.

Finally, by revealing how identity is constructed and reconstructed, a discursive approach can reveal not only the monolithic formulation of a single identity, but also the conflictual nature of competing identities as revealed in discourses (Wæver, 1998, p. 102). As Diez notes, by viewing a particular topic of study, for example Europe, as a “discursive battlefield”, the political territory reveals discursive linkages that help define what can and cannot be discussed (2001). Rather than a focus on mere description, this approach can help provide a deeper explanatory understanding not just of the British political environment but also of the associations Britain has with other states, nations and unions. As such, it is a theoretical framework designed to explain international relations.

How to find meaning in discourse

Three linguistic devices are utilised to reveal meaning. Roxanne Doty (1993) has ably employed these techniques from her study of US policy in the Philippines, and I draw on her work, as well of those of others. These concepts are predication, presupposition and subject positioning, and although they are interconnected, I will briefly explain them individually for the purposes of clarification and convenience. Firstly, predication views discourse as a system of signification, which, via linkages and processes of differentiation and equivalence, suggests an analytical study of language practices. Milliken and Sylvan (1996) offer an adroit application of how predicate analysis presents a more critical interpretation of foreign policy via gendered distinctions between North and South Vietnam. The nexus pits North Vietnam as the masculine entity – with “hard” targets, “tough” opponents and a “harsh” landscape; while South Vietnam is constructed as feminine – with “soft” targets and “squabbling” allies (1996). Predicate analysis, therefore, focuses on how verbs, adverbs and adjectives add meaning to nouns. It looks at how the object (the Other) is linguistically constructed and imbued with characteristics by the subject (the Self).

Secondly, presuppositions are made to formulate background knowledge that takes something for granted and help set the scene for a particular reality to be true. They are also an important textual mechanism for examining what elements of an entity, in this case Europe, are established before the debates take place. For example, Biebuyck argues:

To say we are ‘disappointed’ or ‘surprised’ in Europe due to recent political events prompts an even more fundamental question: what naturalized assumptions, about Europe and its form of politics, made disappointment and surprise normal responses? (2010, p. 162)

As such, we do not start from an empty page with our perceptions, be they Europe or any other political entity, but have pre-existing notions about what attributes a phenomenon has and what expectations are reasonable for what it does. Presuppositioning, therefore, helps uncover the assumptions we have and reveals how Britain, Europe and other subjects and objects are formulated according to these ideas.

Finally, subject positioning refers to the fact that subjects and objects are always produced in respect of other subjects and objects. Predicates and presuppositions, subsequently, can be positioned to reveal relationships based on commonality as well as conflict. Extreme forms of binarisation permeate negative meaning into constructing the Other, and thus define the Self as superior. One such notable example is that of the European perception of the Balkans that acted as a prelude to Western involvement in the Bosnian War of 1991 to 1999. Hansen argues that the Balkans were perceived as barbarian, violent, irrational and underdeveloped, thus constructing Europe as its antithesis: civilised, controlled, rational and developed (2006). Additionally, discursive practices need not be exclusively wedded to the construction of binary opposites but might also include processes of linking and similarity.

The textual mechanisms of presupposition, predication and subject positioning are important because, when employed, they not merely reveal the perceptions the Self has of an Other, but also help construct a diversity of Others. The interwoven and multiple natures of the various linkages reveal different nuances of difference, rather than a single, monolithic disparity. A discourse, therefore, should not be read as if it functions as a solitary, self-enclosed harbinger of meaning, but as a constellational set of linkages containing relations and hierarchies to other components. Subsequently, the perceptions British decision-makers have contain presuppositions that construct Europe as a series of particular ‘truths’, and various qualities are inscribed into other entities that reveal either linking or differentiation.

However, how can these linguistic concepts be practically employed? Neumann (1996, p. 2), in his study of Russia, utilises Todorov (1984) to ask three questions of each text: what is the framework of knowledge within which the European Other is seen? What moral judgement is made of the Other? What relationship is proposed between Russia and the European Other? Within a European context, Wæver asks the following:

What are the powerful categories on which each argument rests and how are they related? Are some concepts tied together as necessarily companions (e.g. ‘us’, Europe, Germans, civilization), are some presented as self-evident opposites (for example, Balkan and peace or nationalism and Europe)? (2005, p. 41)

Firstly, I ask several similar questions of each text in order to extrapolate meaning and assemble the predicates, presuppositions and subject positioning. The predicates are highlighted first as they show how meaning is produced via the production of certain qualities. Presuppositions are then enumerated as they provide the background knowledge. Lastly, subject positioning exposes the relational position between the various subjects and objects. Hence, the concepts of presupposition and predication construct various subjects and objects while the relationships between them are the subject positioning. Figure 1.1 shows these methodological steps taken.

Figure 1.1 Articulation of representations

The second layer: Self/Other analysis

The assumptions of Self/Other analysis

An identity can only exist in relation to one that it is not. The claim that I am a European, for example, only makes sense if we are able to understand the wide array of non-European identities, be they Asian, African, Latin American, and so on. The Other does not merely nominally influence the Self for the Self’s identity to be configured, but the Self’s identity, shaped by several factors of socialisation, can only be constituted in relation to what it is not (Rumelili, 2004, p. 29). Political identities, consequently, do not appear to exist without the distinction between Self and Other. While accepting these assumptions, I would also add another important dimension to the concept of the Self being configured solely through difference. I would like to argue that sameness and not just difference can function as a shaper of the Self’s identity. There are a number of reasons for this important inclusion.

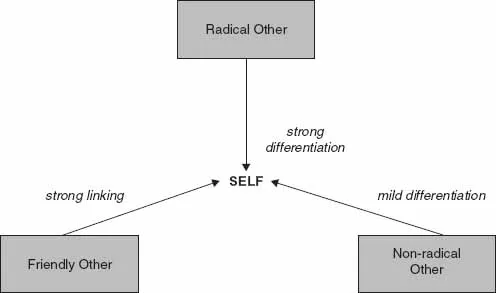

To begin with, the radical Other can be defined as any identity that sits in stark opposition to the Self. It is difference reified and solidifies binary oppositions, such as good versus evil, rational versus irrational or civilised versus uncivilised. However, how is the radical Other not the only actor within the process of identity formation? To take two examples, the radical or hostile Other might have the effect of inextricably forging two near-Selves together in the pursuit of a common agenda against it. Firstly, Banerjee, in his analysis of identity formation in Colonial India, highlights Jawaharlal Nehru’s invocation of the Self–Self opposition within colonial India to counter the common Other. He cites the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, in revealing the importance of how distinctive identities can be synthesised for the purposes of mobilisation: “[i]t is all the more astonishing and astounding … that such things [violence], which made the common foe of all the communities – British Imperialism – laugh in unholy glee, should have at all happened” (in Gopal, 1984, p. 38). Banerjee further explains that in order to quell the violence occurring between Hindus and Muslims, Nehru sought to “discipline elements of the group self through the specter of the other” (1997, p. 38). Hence, what are perceived as deep-running historical, cultural and religious differences become moderated and a common identity is constructed to deal with the universal threat. The second example concerns the security practices of the Cold War. The threat of the USSR – the radical Other – encouraged a level of cooperation among European states that might not have happened had the threat not existed. That is, less powerful countries, by lacking the means or resources, had to bandwagon by identifying themselves with more powerful ones in the hope of realising their interests. As such, Delanty accurately highlights that an all-encompassing European identity “was a Cold War construct shaped and defined by the global confrontation of capitalism and communism” (1995, p. 15).

Finally, by embodying the notion of different levels of difference, empirical analysis becomes much broader by not concluding that all practices and policies are played out in a political environment of perpetual conflict. Friends, and not just foes, define national identities. For example, Hansen reveals how the processes of both equivalence and difference might be revealed in the concept of ‘democracy’. As a privileged identity, it creates a set of relations with other states on the basis of their ‘democratic potential’, and also situates this identity within a structure of spatial and temporal difference because not all states can be regarded as adequately democratic (2006, p. 25).

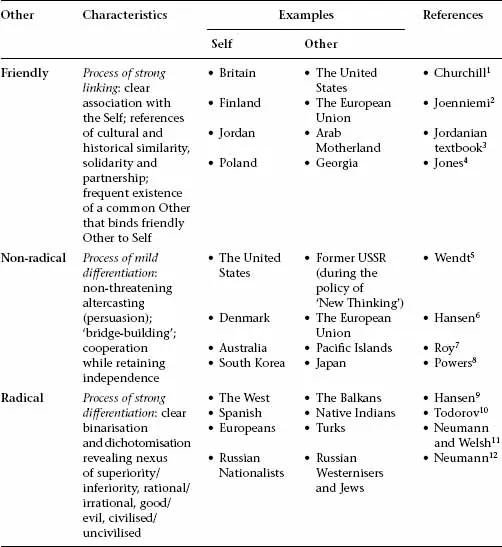

Friendly, non-radical and radical Others

As identity is multilayered and constructed from a variety of sources, Others can be categorised as friendly, non-radical and radical. The interrelatedness of actors in the political arena is as governed by non-radical actors as by radical ones. The process of clear and lucid differentiation and subsequent hostility implicit in defining the radical Other does not reveal a comprehensive picture of how actors perceive and define one another because antagonism is but one source of meaning. In addition, as iterated by Wæver (2002, p. 24), unadulterated difference is less information-rich than more nuanced structures of differentiation. The Other should not be perceived as a pantomime villain and may well exhibit characteristics that although foreign are not necessarily repugnant.

Part of the dominance of the perception of the radical Other stems from the security practices of the Cold War. Hansen, for example, has argued that the simplistic notion of the overtly threatening Other has been coloured by these practices during the post-Second World War period, and that its confrontational legacy still continues to infuse the perceptions we have (1997, p. 390). Similarly, judgements that hinge on singularities – West versus East, Christian versus Muslim or the economic North versus South, to take a few examples – tend to deny the multiplicity of national and regional positions that might not be so easily reducible to a homogeneous mass. This is not to deny that identities cannot collectively embody a diverse transnational group or that a Self cannot be embodied in a larger configuration or entity, such as Europe for example, only that caution must be displayed in presuming that Self/Other necessitates an overriding black/white distinction. In short, Self/Other is more of a multifaceted spectrum than the process of radical Othering presupposes. Figure 1.2 diagrammatically represents this constellational process.

Table 1.1 outlines characteristics and examples of friendly, non-radical and radical Others. Four examples, along with references, are provided for each category. Suffice to say, the sources used are for explanatory purposes only and do not necessarily indicate the individual author’s attitude towards the state, nation or group being examined. Others can be internal (residing within the boundaries of the entity regarded as the Self) or external to this entity. Others may also be real or imagined/symbolic. They might also be regarded as radical within one era, non-radical or friendly in another, or even unnoticed or non-existent at a different stage. Such a situation is context, issue, time and event dependent and is an endemic feature of the ever-evolving nature of identity construction. Subsequently, because identities are fluid, the configuration of Others is captured at a particular point in time. Although a common configuration is to construct the Other as a singular entity, this does not exclusively need to be the case as the development of national identity hinges on a continuous reconstruction and search for Others from which to formulate the Self. Finally, since my focus is to reveal how national identity is represented by the process of Othering, the examples I provide are states, transnational entities, and ethnic and political groups. Needless to say, this in no way implies that Others must be formulated in this way.

Figure 1.2 Othering and the Self

Table 1.1 Friendly, non-radical and radical Others

Methodology

Historical events

The historical events focused on are the 1975 Referendum on Continued Membership of the Common Market, the 1993 ratification of the Maastricht Treaty and the 2009 enactment of the Lisbon Treaty. There are three main reasons why they have been chosen. Firstly, they can be classed as ‘critical junctures’ in that established arrangements of identity become destabilised and reconfigured. The events can be labelled as crises because they all caused British political elites to define and redefine themselves in terms of what meaning Europe had for them. In this sense, the 1975 referendum remains the only UK-wide vote on European membership to date. Unlike general ele...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Theory and Method

- 2 The European Communities Membership Referendum

- 3 The Maastricht Treaty

- 4 The Treaty of Lisbon

- 5 Accounting for Change: The Evolution of British National Identities

- Conclusion: Post-Lisbon and British National Identity

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Appendix 3

- Notes

- References

- Index