![]()

Theory – Structural Transformation of the Global Public Sphere?

A clear theoretical model is vital if we are to take stock of the international and intercultural effect of media and forms of reporting of such different types as television, radio, print media, Internet, direct broadcasting by satellite, international broadcasting and international reporting. In the literature on globalization dealing with international communication, models of any kind are thin on the ground. Manuel Castell’s famous three-volume work, The Information Age, does without almost any schematic models.1 The same goes for multi-authored volumes in this field.2

The present work draws on systems theory to describe the globalization of mass communication. We may divide the key characteristics and conceptual tools deployed here into three fields:

• | system connectivity |

• | system change |

• | system interdependence |

Before discussing more closely the core concepts of ‘connectivity’, ‘change’ and ‘interdependence’ linked with the concept of system, it is vital to shed light on the frequently ambiguous concept of system itself. Cross-border communication is defined very unsystematically in the globalization literature, sometimes as inter- and transnational and sometimes as inter- and transcultural communication. ‘Cross-border’ thus describes those processes of information exchange in the course of which system borders, of the nation-state or culture, are transversed. Almost all contemporary attempts to grapple with globalization theoretically that tackle issues of communication emphasize the nation-state or culture. The focus tends to be on the state, but sometimes it is on cultural areas, at times also labelled ‘civilizations’. The idea of ‘networking’ is anchored in the assumption that the world features a number of poles which can be networked; a web is ultimately nothing without its nodal points.

The notion of network-like communication between actors who can be ascribed to states or cultures is problematic. This is apparent when one considers that these poles of the system are in principle equal. They can be regarded as subsets of one another depending on the situation. States may be parts of cultures – and vice versa. The resulting web of communication appears to resemble the kind of optical illusion whose content changes as one changes one’s perspective. When the Uighurs, a Muslim minority in western China of Turkmen origin and thus related to the peoples of Central Asia, use media from beyond the national borders, should we regard them as actors practising international or intercultural communication?

Quite obviously, it depends which aspect of the analysis we wish to focus on. A web emerges consisting of several dimensions. These complications are rooted in the fact that ‘state’ and ‘culture’ involve differing implications for communication, each of which has its own justification. In one case, communication between actors describable in terms of constitutional law or sociology (governments, NGOs, etc.) takes centre stage. In the other, the focus is on exchanges between subjects and groups in their capacity as bearers of linguistically and historically imbued norms, ways of life and traditions. Both perspectives may be important, as is apparent wherever state and cultural borders are not identical and cultural identity rivals the power of the state. Tribal cultures in Africa, for example, often extend across state borders, highlighting the advantages of scrutinizing both the international and intercultural dimensions of cross-border communication processes.

The existence of cultural areas such as the ‘West’, the ‘Islamic world’, the Indian subcontinent and Latin or German-speaking Europe is an additional factor making analysis more difficult. Such areas gain cohesion across state borders only with the help of mass media, adding a third dimension of regionality to the theoretical model. A debate on globalization restricted to the ‘local’ and the ‘global’ while neglecting the ‘regional’ would lack complexity. The immigrant cultures that we hear so much about, which communicate across borders and form ‘virtual communities’, provide further evidence of the value of examining international and intercultural communication as a unity. The division into the spatial levels ‘global’, ‘regional’ and ‘local’, intended as a heuristic and relevant to both dimensions of state and culture, is not contradicted by migration. Immigrants also communicate either locally, regionally or globally, even if the spatial parameters are the reverse of those of settled populations, as their local culture (their home country) is, so to speak, located in global space and they can develop a second locality only slowly.

System connectivity

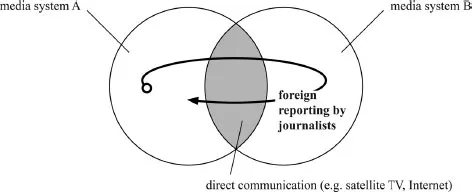

Phenomena of system connectivity, sometimes called interconnected-ness in the literature, describe the extent, speed and intensity of the international or intercultural exchange of information. Connectivity may be generated between entities, however defined, through various means of communication. Alongside mediated interpersonal communication (telephone, e-mail, letter, fax, etc.) we can distinguish the following fields of communication which depend on mass media (figure 1.1):

(a) direct access to the range of communicative services produced by another country/culture (Internet; direct broadcasts by satellite; international broadcasting (special television and radio services in foreign languages broadcast to other countries); imports/export of media);

(b) access to information and contexts in another country or cultural area conveyed by journalism (international reporting on television, radio, the press; corresponding media services on the Internet).

While this list makes no claim to completeness, it is clear that direct routes of access to cross-border communication are in the majority. One of the key factors shaping the globalization debate over the last decade was thus the fact that the number of means of transmission and the exchange of information beyond borders has increased dramatically. The ‘new media’ have set the overall tone of the debate since the 1990s, effectively distorting it, as the ‘old media’ have largely been ignored. In particular, the role of international reporting in the process of globalization has suffered a complete lack of systematic treatment. The technologically possible direct interleaving of national media areas, which people could previously experience only through the information conveyed by international journalism, has proven a fascinating and bothersome phenomenon for researchers.

Figure 1.1 Forms of cross-border mass communication

Source: author

However, it is far from certain that the new media, regardless of their many new forms, characterize the processes of globalization more than national journalism and international reporting. We therefore have to take both fields into account when designing our theories. Despite the rise of the new media and the mounting flood of information available on the Internet, the significance of journalism as intermediary has by no means diminished. Foreign media accessible via satellites and cables also represent a form of journalism, though one which arises outside of one’s own media system. This means that the media user receives direct access to foreign journalistic cultures. Not only this, but the Internet has failed to oust even domestic journalism: journalistic mediation is in fact ever more significant to how people organize their lives at a time when the quantity of information is growing. If at all, online information services can replace the international reporting provided by national media only among small informational elites.

The concrete form of connectivity via the new media depends on a range of technological, socio-economic and cultural parameters:

Technological reach and socioeconomic implications of media technology. The nation-states and cultural areas of this planet are characterized by very different technological capacities for transmission and reception in the field of satellite broadcasting, depending on the prevailing political and financial parameters. The same goes for the Internet. Regardless of the strong increase in the number of connections, a ‘digital divide’ exists, above all between industrialized and developing countries, which restricts connectivity substantially.

User reach. The debate on the globalization of the media all too often fails to distinguish between technological reach and user reach. The number of those who use a technology per se lies below the technologically possible use – and cross-border use is of course only one variant of the use to which the new media may be put. We cannot simply assume that it is the primary form. Our eagerness to wed globalization to a normative agenda should not blind us to the fact that the Internet may be a misjudged medium that is contributing far more to intensifying local connections (e-commerce, etc.) than to creating cross-border networks.

Linguistic and cultural competence. To communicate with people in other states and cultural areas or to use their media generally requires linguistic competence, which only minorities in any population enjoy. To avoid dismissing cross-border connectivity as marginal from the outset, it is vital to distinguish between various user groups – globalization elites and peripheries. Connectivity is without doubt partly dependent on the nature of the message communicated. Music, image, text – behind this sequence hides a kind of magic formula of globalization. Music surely enjoys the largest global spread, and images surely occupy a middle position (for example, press photographs or the images of CNN, also accessible to users who understand no English), while most texts create only meagre international resonance because of language barriers. This issue is central to the evaluation of global connectivity as a more or less ‘contextualized’ globalization. Images in themselves do not speak. They require explanatory text to transport authentic messages – and it is questionable to what extent such messages can overcome borders.

Connectivity in the field of international reporting also depends on the international department’s printing or broadcasting capacities, the quality and quantity of technical equipment and correspondent networks. All these resources have an influence on the presence of other countries and cultures in the media of one’s own country. Foreign reporting has always been a struggle because of lack of resources, particularly in terms of staff and funding. Even the largest Western media have, for example, no more than one or two permanent correspondents in Africa, a continent with more than fifty states. CNN, seemingly the exemplary global broadcaster, has no more than a few dozen permanent correspondents.

International journalism should be seen as a virtual odyssey. More than domestic journalism, it struggles daily to reduce the mass of newsworthy stories from the two hundred or so states of the world to a manageable form. In principle, the notion of a world linked globally through the media assumes that different media systems increasingly deal with the same topics. Moreover, the lines of reasoning deployed in this process would also have to ‘cross borders’. Homogenous national discourses, with their quite unique ways of looking at international issues, would increasingly have to open up to the topics and frames of other national discourses (which does not mean standardization of opinion, as this would involve a more advanced form of cultural change and the development of a global ‘superculture’, which is another issue).3

To increase the connectivity of the journalistic systems of this world, the resources available to the media are just as important as the linguistic and cultural competence of the journalists.4 In some ways, the issue of the connectivity of journalism appears in a new light under conditions of globalization. While media may compete in destructive fashion as described above, multimedia collaboration may help improve the quality of each individual medium. The Internet as a source for journalism is surely the perfect example. Yet here too it is crucial to distinguish theoretically between technologically possible and actually practised use.

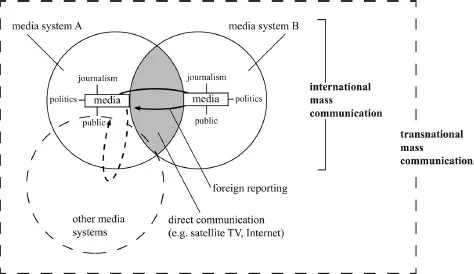

Connectivity may ultimately occur within global communication not only between producers and consumers in various nation-states and cultural areas – that is, internationally and interculturally – but also via a transnational (or cultural) media system. Here, media and media businesses would no longer have a clear-cut national base, but would emerge as ‘global players’. The idea of a world linked through communication is anchored in the assumption that globalization is more than the sum of the links between its components. The structure of the system underlying the global media landscape would change if new supersystems similar to the United Nations or large NGOs such as Greenpeace developed in the media field. The media are in principle also capable of transnationalization, so that alongside national systems networked with one another, a second global system might also arise (figure 1.2).

Contemporary notions of what such a transnational media system consists of are however still very nebulous. Apart from a few global agreements brought into being by the major transnational trade organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) (in the copyright protection field for instance; see chapter 8, p. 143), there are only a few transnationally active corporations which can be called ‘global players’ (see chapter 9). Regardless of the existence of such businesses, transnational media, that is, programmes and formats, are extremely rare. CNN, frequently mentioned as the perfect example of a leading global medium that encourages exchange of political opinion worldwide, by concentrating on transnational programmes, seems to come closest to fitting this vision. Yet even this case is problematic, for CNN is no uniform programme, but consists of numerous continental ‘windows’. There are many ‘CNNs’, but no complete global programme. Through the proliferation of satellite programmes in the last decade, CNN has lost its elevated position and is now merely a decentralized variant of an American television programme, whose country of origin remains easily recognizable in its agenda and framing. CNN tends to be a mixture of characteristics of the American system and the target system of the specific window; it is thus at best a multinational but not a global programme.

Figure 1.2 International and transnational media connectivity

Source: author

For want of concrete role models, a transnational media system remains largely a utopia. Individual large national media systems such as the American or binational services such as the Franco-German broadcaster Arte can supplement but by no means replace their national counterparts. The transnational media field is still largely devoid of formal diversity.

System change

In the second theoretical field, the focus is no longer on grasping the extent and type ...