- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Paper is older than the printing press, and even in its unprinted state it was the great network medium behind the emergence of modern civilization. In the shape of bills, banknotes and accounting books it was indispensible to the economy. As forms and files it was essential to bureaucracy. As letters it became the setting for the invention of the modern soul, and as newsprint it became a stage for politics.

In this brilliant new book Lothar Müller describes how paper made its way from China through the Arab world to Europe, where it permeated everyday life in a variety of formats from the thirteenth century onwards, and how the paper technology revolution of the nineteenth century paved the way for the creation of the modern daily press. His key witnesses are the works of Rabelais and Grimmelshausen, Balzac and Herman Melville, James Joyce and Paul Valéry.

Müller writes not only about books, however: he also writes about pamphlets, playing cards, papercutting and legal pads. We think we understand the ?Gutenberg era?, but we can understand it better when we explore the world that underpinned it: the paper age.

Today, with the proliferation of digital devices, paper may seem to be a residue of the past, but Müller shows that the humble technology of paper is in many ways the most fundamental medium of the modern world.

In this brilliant new book Lothar Müller describes how paper made its way from China through the Arab world to Europe, where it permeated everyday life in a variety of formats from the thirteenth century onwards, and how the paper technology revolution of the nineteenth century paved the way for the creation of the modern daily press. His key witnesses are the works of Rabelais and Grimmelshausen, Balzac and Herman Melville, James Joyce and Paul Valéry.

Müller writes not only about books, however: he also writes about pamphlets, playing cards, papercutting and legal pads. We think we understand the ?Gutenberg era?, but we can understand it better when we explore the world that underpinned it: the paper age.

Today, with the proliferation of digital devices, paper may seem to be a residue of the past, but Müller shows that the humble technology of paper is in many ways the most fundamental medium of the modern world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access White Magic by Lothar Müller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The Diffusion of Paper in Europe

1

Leaves from Samarkand

1.1. The Arab Intermediate Realm

Paper is a protean substance. It not only refuses to be restricted to a single purpose, it also eludes any attempt to reliably pinpoint its origins. Its roots undoubtedly lie in China, but unlike the European printing press, it is not an invention that can be precisely dated. There is, of course, Ts'ai Lun, the high-ranking court official who, with the support of the emperor, introduced paper on a large scale as a less expensive writing material for administration in 105 ad. But the new material he presented was not an invention plucked from thin air; it was the result of improvements to an older production technique. Modern historians trying to trace the gradual, long-term development of papermaking have uncovered a kind of “proto-paper,” derived from plant fibers, which was produced by imitating the methods used to make felt, as well as silk or cotton wadding—but this was still a long way from writing paper. Once a process has become established in the world, it can seem obvious in retrospect. In actuality, though, it must evolve step by step.4

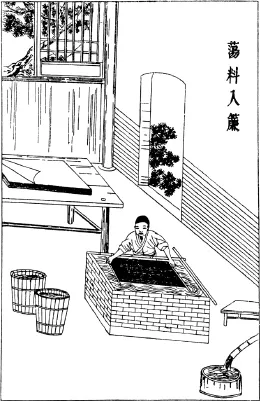

Basic Chinese papermaking can be described as follows: “The raw material generally used by Chinese papermakers was the bast fiber of the paper mulberry, which was soaked in water with wood ash and then mechanically processed until the individual fibers separated. To make sheets of paper, screens were employed consisting of cotton or hemp fabric stretched on a wooden frame. The screen floated in water and the fibers were poured onto it from above and distributed evenly by hand. The screen was then lifted out of the water and set out to dry with the sheet of paper on it. Only afterwards could it be used for another pass. The daily output of a Chinese papermaker was therefore limited to just a few dozen sheets.”5

Ts'ai Lun's primary improvement lay in the expansion of the resource base for paper production. According to a chronicle from 450 ad, it was Ts'ai Lun who had the idea to use pieces of hemp, textile scraps, and the remains of fishing nets in papermaking. Essentially, however, paper manufacture arose anonymously and gradually. As it proliferated in China, productivity increased with the introduction of flexible bamboo screens and a wide variety of applications for paper emerged. “It was not just a writing surface, it was used to make windows and doors, lanterns, paper flowers, fans and umbrellas. Toilet paper was produced on a massive scale as early as the ninth century, while paper money was a generally accepted means of payment in the tenth century.”6

An old tale based on Arab sources describes the first movement of paper from the East to the West. The story says that during a battle in the year 751 between the Arabs and Turkish troops, who fought with Chinese reinforcements, Chinese papermakers were taken prisoner by the Arabs. According to this account, the prisoners were brought from Taraz in Tashkent, the site of the battle, to Samarkand, where they were forced to reveal the secrets of their art. From that point on, paper was produced in and around Samarkand, which the Arabs had conquered in the early eighth century—paper that was in no way inferior to that of the Chinese.

What modern narratives of the history of paper take from this tale is that military conflicts in Central Asia may have accelerated a transfer that had probably begun centuries earlier. The acceleration and violent conquest of secret knowledge from the East as recounted in military history took place against the backdrop of the long-term east-to-west movement chronicled in the history of commerce. The Silk Road was pivotal to the transfer of paper. It was via the routes of the Silk Road that paper had reached Central Asia as a commodity long before Chinese prisoners of war could be forced to give up the secrets of its production. The Silk Road was also a paper road. From this perspective, papermaking was not so much a technology adopted on a specific date as it was a cultural technique that slowly seeped into the Arab world. The inclusion of Chinese paper in long-distance trade triggered the double step that generally takes place when exclusive knowledge is transferred in the form of goods: first a product is imported, then the ability to produce it. The high cost of importing goods over lengthy distances made this kind of double step attractive.

Arab papermakers may have initially continued to use floating screens until the “pour method” was gradually replaced by the dip method. But regardless of the specific modifications made to the technique for creating sheets of paper, Arab papermakers had to adapt the production process to the climatic conditions in their world: they had to keep water consumption to a minimum and find a replacement for the main raw material in Chinese paper, the inner bark of the paper mulberry. It was, above all, this pressure to adapt that pushed the rags, used textiles, and cordage which had at most played a supporting role in China to the center of Arab paper production.

This was the birth of a proto-model for the type of recycling in which a material—such as metal—is not just reclaimed from waste in a different form, but a new, structurally different material is created instead. Paper was henceforth a man-made substance constructed from raw materials that were, for their part, a product of civilization. Granted, even the paper mulberry trees of the Chinese and the papyrus reeds of the Egyptians were not purely “products of nature” since the energies of the civilization around them flowed into their cultivation. But rag paper was free of the natural limits imposed on the propagation of both the paper mulberry native to subtropical southern China and the papyrus of Egypt. Its raw materials could be found wherever people lived, wore suitable clothing, and engaged in trade. Thanks to this freedom from natural, locally bound resources, paper was essentially in a position to spread universally. It took the nomadic nature it already possessed as a long-distance trade product and absorbed it into its material structure, offering little opposition to the surmounting of local production restrictions. As early as the eighth century, paper mills were built in Baghdad, then on the Arabian Peninsula, in Cairo, and in Syria, where paper was produced in Damascus, Tripoli (now in Lebanon), and Hama from the tenth century, and soon began to be exported as well. A Persian traveler in the eleventh century reported that traders in Cairo wrapped their wares in paper, and even in the tenth century, Syria was exporting not just paper to North Africa but also the art of papermaking.7

Though papermaking gradually lost its ties to natural raw materials as production shifted to raw materials that were themselves products of civilization, this certainly did not mean that its resource base was boundless. Its raw materials were obtained from cities and villages, not fields and forests, so from the Arab civilization of the Middle Ages until well into the nineteenth century, paper production remained closely linked to factors such as population development and textile production and, on account of its association with ropes and rigging, to the evolution of trade and seafaring.

The history of paper's arrival in Samarkand and its diffusion through the Arab empire was not traced in detail until the late nineteenth century. Joseph von Karabacek, an orientalist and director of the Imperial Library in Vienna, played a major role in this. His essay Arab Paper (1887) was based on the study of over 20,000 paper fragments, discovered in the winter of 1877–78 near the Middle Egyptian city of Al-Fayyum and in Hermopolis, which had entered the papyrus collection of Austrian Archduke Rainer. Karabacek translated the fragments dating from the eighth to the fourteenth century and described the wide variety of scripts, colors, and paper formats employed for administration. He mentioned as well the extraordinarily thin “bird paper” that was used for “pigeon post” correspondence and was also popular for love letters. Karabacek published his own translation of the Umdat al-kuttab, the only surviving eleventh-century Arabic treatise on papermaking. Finally, he presented a selection of the papers to the public in an exhibition and assembled a catalog which documented paper's wide range of uses and geographic distribution.8

At the same time, the botanist Julius Wiesner was researching the material composition of Arab paper using microscopic methods developed for studying plant physiology. He published his findings parallel to Karabacek. The two worked independently of each other, but they followed the same hypothesis—namely, that the Arab world was not just a transit station on paper's journey from China to Western Europe, but that Arab civilization permanently changed the technique for making paper and, in doing so, made a substantial contribution to the upsurge in European paper mills from the thirteenth century onward. With polemical verve, Karabacek pursued his goal of demonstrating that Arab civilization was the source of “rag paper” made from linen scraps and hemp fibers and was therefore the model for European paper production. This parallel historical-antiquarian and scientific-microscopic analysis of Arab paper in Vienna received a few welcome critical responses from the experts, but it barely made an impression on the general consciousness of Europeans. In part, this was because Karabacek and Wiesner were not so much filling a gap in knowledge as they were breaking down an old transmission paradigm.

When Joseph von Karabacek called his essay on Arab paper a “historical and antiquarian enquiry,” there was a programmatic accent on this subtitle. What he meant was that his work described Arab paper with the kind of methodological diligence and attention to detail that had previously been reserved for Greek and Roman antiquity. By placing Arab paper in the position of origin with respect to European paper—a position occupied by Chinese paper in Arab culture itself—Karabacek drew attention to a divide that had barely been perceived as such in Europe: the divide separating the European paper of the modern era from the papyrus of the ancient world.

In his commentary o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Thanks

- PROLOGUE: The Microbe Experiment

- PART ONE: The Diffusion of Paper in Europe

- PART TWO: Behind the Type Area

- PART THREE: The Great Expansion

- EPILOGUE: The Analog and the Digital

- Bibliography

- Image Credits

- Index

- End User License Agreement