- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Immigrant Labor and the New Precariat

About this book

Immigration has been a contentious issue for decades, but in the twenty-first century it has moved to center stage, propelled by an immigrant threat narrative that blames foreign-born workers, and especially the undocumented, for the collapsing living standards of American workers. According to that narrative, if immigration were summarily curtailed, border security established, and ""illegal aliens"" removed, the American Dream would be restored.

In this book, Ruth Milkman demonstrates that immigration is not the cause of economic precarity and growing inequality, as Trump and other promoters of the immigrant threat narrative claim. Rather, the influx of low-wage immigrants since the 1970s was a consequence of concerted employer efforts to weaken labor unions, along with neoliberal policies fostering outsourcing, deregulation, and skyrocketing inequality.

These dynamics have remained largely invisible to the public. The justifiable anger of US-born workers whose jobs have been eliminated or degraded has been tragically misdirected, with even some liberal voices recently advocating immigration restriction. This provocative book argues that progressives should instead challenge right-wing populism, redirecting workers' anger toward employers and political elites, demanding upgraded jobs for foreign-born and US-born workers alike, along with public policies to reduce inequality.

In this book, Ruth Milkman demonstrates that immigration is not the cause of economic precarity and growing inequality, as Trump and other promoters of the immigrant threat narrative claim. Rather, the influx of low-wage immigrants since the 1970s was a consequence of concerted employer efforts to weaken labor unions, along with neoliberal policies fostering outsourcing, deregulation, and skyrocketing inequality.

These dynamics have remained largely invisible to the public. The justifiable anger of US-born workers whose jobs have been eliminated or degraded has been tragically misdirected, with even some liberal voices recently advocating immigration restriction. This provocative book argues that progressives should instead challenge right-wing populism, redirecting workers' anger toward employers and political elites, demanding upgraded jobs for foreign-born and US-born workers alike, along with public policies to reduce inequality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Immigrant Labor and the New Precariat by Ruth Milkman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Organisational Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Brown-Collar Jobs: Low-Wage Immigrant Workers in the Twenty-First Century

Migrants provide a way in which workers in the native labor force are able to escape the role to which the system assigns them.

Michael Piore (1979: 42)

This chapter profiles the immigrant labor force in the twenty-first-century United States – both the unauthorized “illegal aliens” who are the focus of contemporary political controversy and the larger population of immigrant workers with legal status. It highlights the concentration of foreign-born workers in particular occupations and industries and the limited extent to which they compete directly with the U.S.-born. At the bottom of the labor market, this pattern of occupational segregation involves the overrepresentation of foreign-born workers in poorly paid, physically demanding, menial, and often dangerous jobs with limited requirements for English-language proficiency – jobs that most U.S.-born workers seek to avoid. Indeed, this is the basis of the frequent claim that low-wage immigrants are doing “jobs Americans don’t want.” In the past, U.S-born workers had held some of these jobs, but increasingly rejected them in the wake of employers’ deliberate efforts to cut wages and degrade working conditions in the course of the economic restructuring that began in the 1970s. In other instances, such as paid domestic labor, the jobs always had been undesirable but were abandoned by U.S.-born workers – especially workers of color – when the civil rights movement opened up better opportunities.

Occupational segregation between U.S.- and foreign-born workers also helps explain why the influx of low-wage immigrants in recent decades has had little or no effect on the economic status of less-educated U.S-born workers. Although the real (i.e. controlling for inflation) earnings of the latter group have declined dramatically since the 1970s, immigration was not the cause of that wage suppression but, rather, its result. As chapter 3 details, attacks on unions, deregulation, subcontracting, and other forms of restructuring transformed many formerly well-paid blue-collar jobs with decent working conditions into poorly paid, precarious positions that U.S.-born workers then exited. As employers turned to immigrants to fill the resulting vacancies, they created a new category of low-wage “brown-collar” jobs, racially stereotyped as best suited to Latinx immigrants (Catanzarite 2002). Less-educated U.S.-born workers now moved into better-paying, less onerous positions that required English-language proficiency, but which often fell short of the labor standards set in the era of strong unions and state regulation.

Immigration and Occupational Segregation

Because public debate about immigration focuses disproportionately on the unauthorized, it is easy to forget that they constitute less than 5 percent of the nation’s workforce. Foreign-born workers with legal status, most of whom are permanent residents or naturalized citizens, make up a far larger share – about 12 percent in 2017 (Radford 2019). Immigrant workers are also more ethnically diverse than many Americans realize: in 2008, 17 percent were white, 25 percent were Asian, and 1 percent were black, while just under half (48 percent) were Latinx. (That year the U.S.-born labor force was 72 percent white, 2 percent Asian, 12 percent black, and 11 percent Latinx.)1 Belying the stereotype that they are poorly educated, in 2018, 37 percent of immigrant workers aged twenty-five years and older held a four-year college degree, only slightly below the 41 percent of U.S.-born workers in the same age group with that level of education (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2019). In contrast, only 15 percent of unauthorized immigrants aged twenty-five or more held a four-year college degree (Migration Policy Institute 2018).

The geographic dispersion of immigrants has increased in recent years, in contrast to the earlier pattern of concentration in traditional gateway areas such as New York, California, and Florida (Blau and Mackie 2017: 77). Yet the regional distribution of foreign-born workers remains markedly uneven: in 2018, 24 percent of the labor force in the West and 20 percent of that in the Northeast was foreign-born, compared to only 9 percent in the Midwest and 16 percent in the South (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2019). There is also substantial variation within each region. In general, immigrant workers are disproportionately concentrated in geographical areas where economic growth (and thus labor demand) is most robust.

The foreign-born are unevenly distributed not only across regions but also across occupations. They are overrepresented in certain professional fields, such as science and engineering, and as owners of certain types of small businesses, such as dry cleaners and nail salons, whereas in other professional and business occupations their presence is far more limited (Blau and Mackie 2017: 94). Overall, 33 percent of immigrant workers held professional and managerial jobs in 2017, compared to 42 percent of the U.S.-born (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2019); this reflects the slightly lower average educational attainment of the foreign-born population, as well as language barriers and the fact that most professional credentials obtained in other countries are not recognized in the United States.

At the other end of the labor market – of primary concern here – immigrants are strongly overrepresented in fields of employment with the greatest risk of occupational injury and on-the-job deaths. One study found an average of 31 more occupational injuries per 10,000 workers among foreign-born workers than their U.S.-born counterparts, and about 1.8 deaths per 100,000 workers among immigrants for each death among the native-born. Injury and death rates were even higher for immigrants with little or no English-language proficiency. These are conservative estimates, since occupational injuries and deaths tend to be underreported in industries employing large numbers of immigrants, such as construction and meatpacking (Orrenius and Zavodny 2009).

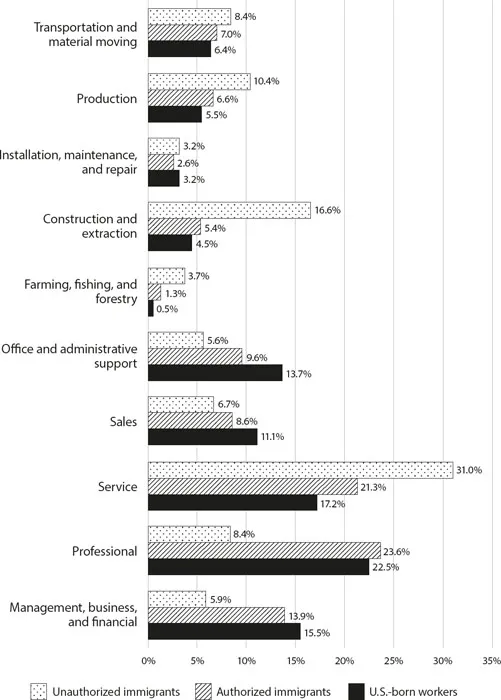

Figure 2 shows the distribution of unauthorized immigrants, authorized immigrants, and the U.S.-born across ten major occupational groups in 2016. Foreign-born workers were a majority in only one of the ten groups, “services,” which includes a wide variety of occupations. Even among these highly aggregated occupational categories, however, the extent of immigrant concentration is striking, especially for the unauthorized. Two-thirds of unauthorized immigrant workers were employed in only four of the ten occupational groups shown in figure 2: service, construction, production, and transportation. Those four groups accounted for a much smaller share – 40 percent – of authorized immigrant workers, and even fewer (34 percent) of U.S.-born workers. By contrast, nearly one-fourth (24 percent) of authorized immigrants were employed in professional occupations in 2016, a slightly higher share than among the U.S.-born (23 percent), and nearly triple the share among the unauthorized.

Figure 2 Major occupational groups, by nativity and immigration status, 2016

Source: Passel and Cohn (2018: 74).

Just as women workers make up the vast majority of the workforce in gender-stereotyped “pink-collar” jobs such as clerical work, child care, and nursing, so too working-class Latinx immigrants make up the bulk of those employed in ethnically segregated brown-collar jobs (Catanzarite 2002). In such sectors foreign-born workers are often presumed to be unauthorized, although in fact many have legal status. Brown-collar jobs are themselves internally gender-segregated: for example, women are the vast majority of immigrant nannies, housecleaners, and home-care aides, while men are overwhelmingly predominant in the ranks of immigrant construction workers. In recent decades the overall extent of occupational segregation by gender has declined somewhat in the United States, but segregation between native- and foreign-born workers has actually increased, especially among women (Blau and Mackie 2017: 95–8).

Figure 2 understates the degree to which employment patterns differ between U.S.-born and foreign-born workers, as there is further segmentation within each of the broad occupational groups shown. Data on more detailed occupational classifications are limited, but the analyses that are available offer a glimpse of far more extensive segregation. For example, one study found that, in 2010, 58 percent of all “graders and sorters” in agriculture, 56 percent of assemblers in high-tech manufacturing, 53 percent of maids and housekeeping cleaners, 52 percent of janitors and building cleaners, and 50 percent of roofers were foreign-born (Singer 2012). Other research shows that, in 2011, 68 percent of dishwashers were foreign-born (Zavodny and Jacoby 2013); and in 2014, almost two-thirds (63 percent) of “miscellaneous personal appearance workers” (including manicurists), 59 percent of plasterers and stucco masons, and 52 percent of sewing-machine operators were foreign-born (Passel and Cohn 2016).

Even these data fail to capture the full extent of occupational segregation between immigrants and U.S.-born workers, however, because the figures are averages for the entire United States, collapsing together regions where immigrants are few and far between with those where a large share of the labor force is foreign-born. In regions of the latter type, such as southern California, immigrants are the vast majority of garment workers, housecleaners, taxi drivers, hotel housekeepers, car-wash workers, janitors, and residential construction workers – among many other brown-collar occupations (Milkman 2006).

The aggregate data in figure 2 reveal the distinctive occupational profile of unauthorized immigrants; but here too more detailed data expose more pervasive segregation. Although unauthorized immigrants were just under 5 percent of the overall U.S. labor force in 2016, they accounted for 31 percent of roofers, 30 percent of drywall installers, 30 percent of farm workers, 27 percent of construction painters, 24 percent of maids and housekeeping cleaners, 22 percent of sewing-machine operators, and 19 percent of grounds maintenance workers (DeSilver 2017). Again, these are national data and therefore, given the uneven geographical distribution of unauthorized workers, understate the degree of occupational segregation.

Unauthorized immigrant employment patterns are also distinctive in other respects. In contrast to the more diverse overall foreign-born population, this group is overwhelmingly Latinx: in 2014, 71 percent of the unauthorized were born in Mexico or Central America and another 8 percent in South America. Fully half lack a high school diploma (Migration Policy Institute 2018). Moreover, the unauthorized are disproportionately vulnerable to illegal employment practices, such as being paid less than the statutory minimum wage or being denied legally mandated overtime pay. Authorized immigrants experience such violations more frequently than their U.S.-born counterparts, but prevalence is far greater for the unauthorized (Bernhardt et al. 2009). In addition, wages and working conditions for unauthorized immigrants have deteriorated significantly since 1986, when “employer sanctions” – penalties for hiring workers without legal documents – were introduced under the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). Among the unintended effects of that legislation was that it led many employers to pass on the added risks and costs involved in hiring unauthorized workers to subcontractors or to the workers themselves (Phillips and Massey 1999).

But the central feature of low-wage immigrant employment is the extensive degree of occupational segregation described earlier, which means that immigrants and natives are rarely competing directly for the same jobs. And, crucially, this form of occupational segregation is racialized, sharpening the boundaries between brown-collar jobs and those considered – by employers and workers alike – as the preserve of U.S.-born white workers. Another dimension of occupational segregation involves educational attainment: immigrants make up about one-sixth of all U.S. workers, but more than half of those who lack a high-school diploma are foreign-born, and many immigrants in this group also have limited English-language skills. Indeed, U.S.-born workers without a high-school diploma are disproportionately employed in less-skilled jobs that require English proficiency, while their immigrant counterparts (who are also younger, on average) are concentrated in labor-intensive manual jobs demanding physical strength and stamina. The latter are the brown-collar jobs shunned by even the least educated U.S.-born workers (Zavodny and Jacoby 2013; Peri and Sparber 2009). Direct competition is further constrained by the geographical unevenness of immigration, which in turn reflects the fact that the foreign-born tend to be more willing than the U.S.-born to relocate to areas where demand for labor is strong, as noted earlier (Blau and Mackie 2017: 5).

“Jobs Americans Don’t Want”

Occupational segregation, reinforced by the racialization of brown-collar jobs, means that the employment patterns of foreign-born workers, especially the unauthorized, are distinctly different from those of their U.S.-born counterparts, especially white U.S.-born workers. But are low-wage immigrants really “doing jobs Americans don’t want,” as is so frequently asserted? Many employers seem to think so, regularly complaining that they cannot find U.S.-born ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Praise

- Series title

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Acknowledgments

- Permissions Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Brown-Collar Jobs: Low-Wage Immigrant Workers in the Twenty-First Century

- 2 Immigration and Labor in Historical Perspective

- 3 The Eclipse of the New Deal: Labor Degradation, Union Decline, and Immigrant Workers

- 4 Growing Inequality and Immigrant Employment in Paid Domestic Labor and Service Industry Jobs

- 5 Immigrant Labor Organizing and Advocacy in the Neoliberal Era

- Conclusion

- References

- Index

- End User License Agreement