![]()

1 Introduction

This book sets out the knowledge you will need to enable you to understand and manage the common psychiatric disorders and psychological problems that you will encounter among your patients in your pre-specialist years. It contains everything you are likely to need for your Finals examination, and then some more. It does not pretend to be a textbook for psychiatrists, but it should provide a useful introduction to the subject even for those students who intend to enter psychiatry or general practice.

The Clinical Approach to the Patient

We start by giving an account of those interview techniques that are necessary in order to evaluate the importance of psychological factors in the individual case. We distinguish between the brief, focused examinations that are appropriate in the general wards and the A&E Department, and the much more comprehensive examinations for inpatients in the psychiatric wards. Next comes a chapter on the mental state examination, followed by chapters dealing with risk assessment, and with the classification, aetiology, assessment, and treatment of psychiatric disorders, and this part concludes with a chapter explaining how you should set about the formulation of an individual patient’s problems in the psychiatric setting.

The chapters in this first part are fundamental to understanding what goes on in a department of psychiatry and are also relevant to work in the general wards. They will help you to elicit data relevant to a proper understanding of a patient’s psychological problems, and then go on to make appropriate plans for treatment and management.

Syndromes of Psychiatric Disorder

The second part of the book gives a general account of the more common syndromes of psychiatric disorder. We start with psychological disorders that commonly accompany physical diseases, and include sections on epilepsy and pain. We then start at the top of a hierarchy of psychiatric disorders: beginning with organic brain syndromes, going on to schizophrenia, and then considering bipolar disorder. The next two chapters deal with internalizing disorders, where people experience subjective distress, First comes a chapter on anxiety, depression and fear disorders, followed by somatic presentations of emotional distress. Next come the externalizing disorders, where abnormalities occur mainly in outwardly observable behaviour: misuse of alcohol and drugs, and eating disorders. We conclude this part with a chapter on personality disorders.

The disorders described in this part are defined in terms of syndromes or collections of symptoms that commonly occur together, and in this respect they are therefore fairly similar to illnesses you will already have come across in general medicine, such as migraine or asthma.

Disorders Related to Stages of the Life Cycle

In the third part we will consider disorders that either take their onset at a particular stage of human development, or are peculiar to a stage of the life cycle. We start with learning disability since this group of disorders reflects problems arising at conception, during intra-uterine development, or from events during or shortly after birth. We then work our way through the life cycle with chapters on disorders of childhood and adolescence followed by sexual and reproductive disorders, and finally disorders of older people.

Epidemiology

We will be giving you figures for each illness in later chapters: here we consider overall rates for any psychiatric diagnosis in various populations. Between a quarter and one-third of the population can be expected to experience a period of mental ill-health in the course of a year, but some of these are self-limiting episodes for which care is not sought. Just over 20 per cent of the population will consult their family doctor with a mental disorder, and in 11 per cent the GP will make a formal psychiatric diagnosis. However, only about 2 per cent of the population are likely to be referred to the mental illness services, and most of these will be dealt with as out-patients.

If we consider consecutive attenders at general practitioners’ surgeries, then somewhere between 25 and 35 per cent of them will meet research criteria for psychiatric illness. Figures for those admitted to medical wards of general hospitals are approximately similar: recent estimates range between 20 and 40 per cent. Most of these illnesses are states of anxiety or depression, and such disorders are usually an integral part of the various physical disorders for which help is being sought (see Chapters 11 and 12 for a fuller discussion). It is for this reason that an understanding of the assessment and management of psychiatric illness is an essential part of your medical training.

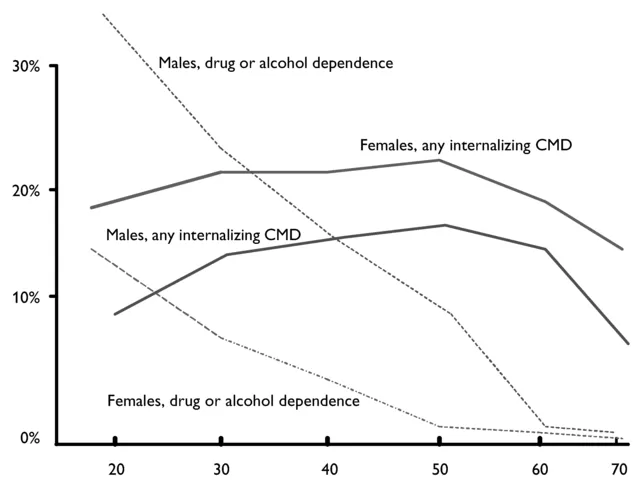

Females are at much greater risk for disorders characterized by depression and anxiety (‘internalizing disorders’), and males have much higher rates for alcohol and drug disorders, and anti-social behaviour (‘externalizing disorders’) (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Rates for any common mental disorder, and drug or alcohol dependence, by age and sex (ONS 2000, data for Great Britain)

Skills to be Acquired

With the help of this book and the opportunity to interview patients, you should aim to acquire the following skills between now and the time that you qualify:

- The ability to take a history from a patient in such a way that you are able to assess the importance of psychological factors.

- The ability to make a short assessment of a patient’s personality and to distinguish it from illness.

- The ability to carry out a mental state examination of a patient with a psychiatric illness, and the ability to assess dementia.

- The ability to adapt your interview techniques to special types of clinical interview, for example brief focused interviews in primary care, on general wards or in A&E departments, interviews with children, with old people, with immigrants and those with communication problems.

- The ability to write a formulation of a patient’s illness.

- The ability to assess an episode of self-harm.

- The ability to assess suicidal risk.

- The ability to take a history from a relative.

Knowledge of Management Procedures

By the time you qualify you should aim to acquire knowledge of the following management procedures. You should aim to cover most of them during your time in the department of psychiatry. It helps a great deal if you have actually seen them carried out, but there is no need for you to have done them yourself.

Medical procedures

- The management of alcohol withdrawal.

- The management of an acutely psychotic patient.

- How to prescribe antidepressant medication

- Giving electro-convulsive treatment (ECT).

Psychological procedures

- (On the general wards)

- How to break bad news.

- Problem solving.

- Talking to aggressive patients.

- Talking to suicidal patients.

- Helping the dying patient.

- (In the paediatric department)

- How to interview a child.

- The management of violent behaviour in hospital settings.

- Emergency procedures under the Mental Health Act.

Prevention of Mental Disorders

It is customary to divide preventive activities into three types: primary prevention, which seeks to prevent a disorder occurring at all; secondary prevention, which seeks to bring early and effective treatment to those who have developed a disorder; and tertiary prevention, which seeks to reduce disability that has developed already.

Primary prevention includes measures to reduce psychosyndromes associated with head injury by seat belts and safer cars; health education to prevent AIDS by reducing promiscuous sexual contact or by use of appropriate contraceptive techniques; health education to provide clear guidance about safe levels of alcohol ingestion, measures to reduce sexual and physical abuse of children and to reinforce the desirability of providing children with a secure, caring environment and so reducing vulnerability to later anxiety and depression. There have been interesting preventive programmes in schools aimed at reducing both bullying and anti-social behaviour, and interventions to promote good parenting practices, which can be provided by psychologists, or brief interventions by family doctors. The arrival of computerized psychological treatments offers promise of much greater availability of preventive interventions.

Secondary prevention is best directed at high-risk groups: young widows, women who have experienced depressive symptoms in pregnancy, and young mothers at high risk of abusing their babies are examples. Post-natal depression can be reduced by visits from health visitors, and child abuse by arranging friendly follow-up visits by nurses.

Tertiary prevention can best be directed at those with mental disorders that will otherwise be long-term and will be associated with great disability: examples would be those with chronic psychosis and young adults with head injury.

Problem Based Learning

In clinical practice, problems, rather than mental or physical disorders, are presented by patients and their carers. The problem presented by the patient may be a symptom of one of a number of disorders and the doctor has to establish from other symptoms and other sources of information the most likely cause of the problem. The cause of the problem may be a mental disorder, but it may be unrelated to a mental disorder. While it is important to diagnose accurately the mental disorder, there are other features of a problem that are just as important such as the risk of death or serious injury to the person, or the best setting to treat the patient (e.g. hospital in-patient unit, hospital outpatient department, at home). Furthermore a patient may present with several new and ongoing problems that may or may not be related. For all these reasons, there is an increasingly widespread view that the teaching of medicine should start from the problems that patients present with rather than learning only about the major disorders patients can suffer from.

Problem based learning refers to the definition of learning goals from the problems that the patient presents with. The medical student lists the main problems that the patient may have and uses these problems to identify the potential disorders and other important related information to decide what to read and learn about. In this way problem based learning fulfils two aims that are not so readily captured in more traditional approaches to learning – to take a set of problems from the clinical setting and directly relate these to what the student needs to learn, and to define the most relevant and salient features of the case. A book such as this can be a source of information about the disorders a person might have and their management. However, it is important that the student does not only generate lists of individual mental and physical disorders that a patient might have from the problems they describe. The student needs to consider the person’s problems in relation to their life situation, the effects the problem might have on other people, if the problem can be seen as a developmental or degenerative issue, and what effect the problem might have in relation to the public as a whole (the public health perspective).

Box 1.1 gives an example of a case to which a student has applied problem based learning. Note that a brief summary of the case capturing its salient features is used as the basis for setting learning objectives, otherwise each case will generate too many learning objectives and there will be a considerable amount of pointless repetition as the student moves from one case to the next. The italics indicate the words that the student has picked out and used to define a learning objective in the order that these words appear in th...