Introduction—The Three Components of Effective Policy Design(s)

Policy design is a branch of the policy sciences concerned with the study of policy processes. It is undertaken with the expectation that such study can generate better or improved ways to construct policies and ensure that maximizing or even optimal results are achieved from the expenditure of scarce governing resources.

But why this should be the case is not immediately apparent. That is, it has long been noted in the policy sciences, and by observers of policymaking more generally, that while some policymaking efforts are well thought out and constructed—or ‘designed’—others are much more arbitrary or capricious. Many formulation situations, for example, involve information and knowledge limits or involve multiple actors whose relationships may be more adversarial or competitive than typically associated with a ‘design’ process and outcome (‘non-design’) (Schön 1988; Gero 1990). That is, not all policymaking is logic- or knowledge-driven, and it is debatable how closely policymakers approximate the instrumental logic and reasoning generally thought to characterize an intellectually driven design situation, in this field or any other (Howlett et al. 2009).

That is, it is well known that designing public policies is a difficult task for a number of reasons, including lack of resources; the existence of corrupt or inefficient bureaucracies and other policy actors who are either incompetent or motivated by values other than doing the public good; the presence of powerful veto players among both state and societal actors who can block even the best thought-out plans; problems of vague goal definition; and poor implementation, evaluation and other policy practices, among others. In these and many other instances, policy decisions and ‘design’ considerations may be more or less absent from policy deliberations, which may be overtly partisan or self-interested and not at all interested in marshaling evidence about ‘what works, when’ in order to attempt to deliver efficient or effective outcomes to policy clients or targets. In such circumstances, evidence and knowledge of best practices can be ignored, and the quality of the logical or empirical relations between policy components as solutions to problems may be incorrect or also ignored (Cohen et al. 1972; Dryzek 1983; Eijlander 2005; Franchino and Hoyland 2009; Kingdon 1984; Sager and Rielle 2013). Policy formulators or decision-makers, for example, may engage in interest-driven trade-offs or legislative or bureaucratic log-rolling between different values or resource uses or, more extremely, engage in venal or corrupt behavior in which personal or partisan gain from a decision may trump all other evaluative criteria.

Even at the best of times, there is a high level of uncertainty in policymaking. The modern policy studies movement has always acknowledged that public policymaking commonly results from the interactions of policymakers in the exercise of power rather than knowledge, but it has also recognized that even when knowledge is predominant, this does not always guarantee the passage or effective implementation of policies or the attainment of desired results (Arts and van Tatenhove 2004; Lasswell 1958; Stone 1988). Even in the best circumstances and with the best of intentions, governments often grapple with complex problems involving situations in which they must deal with multiple actors, ideas and interests in complex problem environments that typically evolve and change over time, making it difficult to secure or retain agreement on which policy alternatives are most likely to succeed.

Nevertheless, it is also a standard trope in the field that better-designed policies are more likely to correctly identify or solve the problems they are expected to address—that is, to succeed—while poorly or non-designed ones are more likely to fail for the same reasons. The modern policy sciences were founded on the idea that accumulating and utilizing knowledge of the effects and impacts of a relatively well-known set of policy means developed over many years of state-building experience can help marshal and utilize resources and accomplish policy outcomes that enhance public value (Lasswell and Lerner 1951; Howlett and Mukherjee 2014). But exactly how such processes occur, why they should lead to effective choices of policy tools or how effective policy tool choices lead to effective outcomes are not well understood.

This is a significant gap in the field, because even in cases of well thought-out, well-intentioned or otherwise well-designed policies, failures occur from time to time (Nair and Howlett 2017; Howlett et al. 2015). This can happen for a variety of idiosyncratic reasons, such as misspecification of problem severity or a shift in the kinds of risks policies were designed to face; this may even be more structural in nature, such as when policies fail due to constitutional or other limitations on state powers (Nair and Howlett 2017).

Understanding policy design, then, is about understanding the differences between these ‘design’ and ‘non-design’ processes, their content and outcomes. Work in this area of policy design is needed; the chapters in this handbook help to develop a better understanding of the components of policy design, its vicissitudes and the logic and practices that influence design, policy, success and failure.

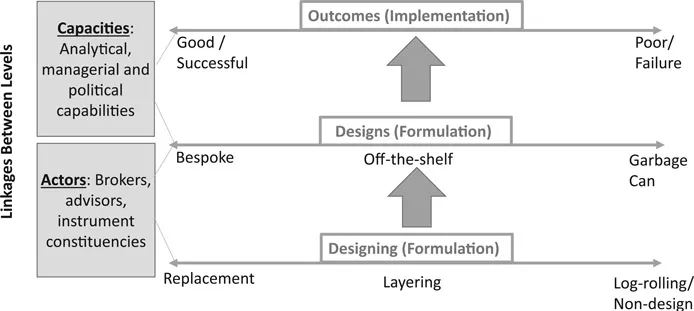

These studies emphasize how three aspects of policymaking must be linked together in a coherent fashion if success is to be achieved: design processes, instrument choices and policy outputs. Designs can promote either first-best (theory-inspired) or second-best (real-world) solutions, but when links between these layers do not exist or are poorly constructed, situations occur in which policymaking is often bereft of a purposive knowledge-inspired endeavor at design (see Figure 1.1).

Exploring these themes, this handbook presents a joint endeavor on the part of many authors to unite the large and burgeoning body of work on policy design into one comprehensive resource. In what follows, each of the three aspects of policy design previously mentioned are set out, along with the literature, key concepts and findings concerning them as background for the more detailed chapters that follow. A summary of the handbook structure is provided before the conclusion. Lastly, the end of this chapter presents a comprehensive reading list representing some of the key contributions that have shaped the field of contemporary policy design

Figure 1.1 Three Elements of Design Effectiveness

What Makes for Superior Design Processes?

As Figure 1.1 illustrates, the overall supposition of design studies in the field of public policy is that a superior process of policy formulation (‘designing’) will lead to a superior set of policy instruments and components (‘design’), which will in turn result in a superior outcome than would some alternate kind of process. Other forms of formulation—such as pure bargaining or log-rolling—are thought to be inferior and do not possess a purposive design orientation. Instrument choices and policies that emerge from them are ones expected to result in an inferior mix of policy tools and elements that, by definition, would typically generate inferior results than would a set arrived at through a better, more informed process.

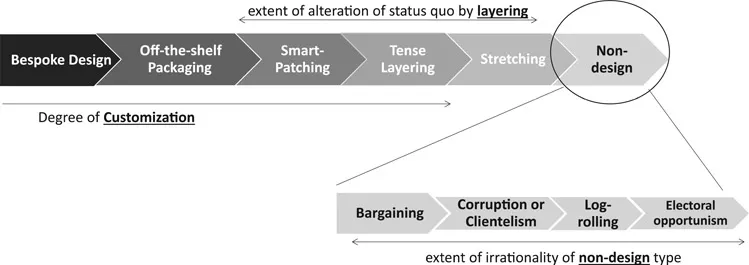

The extent to which a policy process is ‘informed’ by knowledge and evidence, however, depends strongly on the political environment that contains it. Well established studies on the role of institutions in the policy process, for example, have helped to clarify the role of historical and political legacies, policy capacities and design intentions in affecting policy formulation processes and, more recently, in understanding how the bundling of multiple policy elements together to meet policy goals can be better understood and accomplished (Howlett and Mukherjee 2017). This work has helped advance studies of both ‘design’ and ‘non-design’ processes, which are now viewed in a spectrum, as set out in Figure 1.2.

Effectiveness, in this view, serves as the fundamental goal of any design, upon which is built other goals, such as efficiency or equity. An ‘effective’ policy process in this sense means that at the heart of policy design is the formulation of policy alternatives that can achieve government objectives and the idea that a formulation process that is capable of doing this is the most effective. Effective policy design thus embodies a process that falls on the more purposive and instrumental end of the formulation spectrum and entails the intentional undertaking of linking policy instruments with unambiguously outlined policy goals (Majone 1989; Linder and Peters 1984; May 2003; Bobrow 2006).

This involves the organized effort to analyze the effects that policy tools can have on the welfare and behavior of policy targets, as well as using this knowledge to craft policy responses that can, in all practicality, lead to expected policy outcomes (Weaver 2009a, 2009b; Bobrow and Dryzek 1987; Sidney 2007; Gilabert and Lawford-Smith 2012).

Figure 1.2 Design and Non-Design Policy Processes

It is understood that policymakers face various degrees of uncertainty (that comes with limited evidence) as well as ambiguity (that results due to the multiple ways available for understanding a policy problem) (Zahariadis 2008; Cairney 2012, 2016); it is also understood that the knowledge used to inform design can be socially embedded in relationships of political authority (Strassheim and Kettunen 2014). While these considerations are thought to have a strong bearing on how effectively a policy formulation process guided by the design orientation is able to translate policy problems into feasible policy means, they are not, however, thought to completely negate the possibility of design occurring (Turnbull 2017).

What Makes for Superior Tool Choices?

The second level of design activity that must be taken into consideration concerns the actual design itself. That is, not only must a policy process be an effective one, but the mix of tools that emerges from it must also be the same. Policy instrument studies have a long history, but in recent years a greater emphasis upon the effectiveness of tool mixes, rather than individual tool choices, has been a hallmark of the discipline (Hood 2007; Howlett 2011). These studies have increased awareness of the many dilemmas that can appear in the path of the development of effective policy tool or ‘toolkit’ designs as well as the realities of policy implementation that they face on the ground (Peters and Pierre 1998; Klijn and Koppenjan 2012; Doremus 2003; Sterner 2003).

Early studies of individual policy tools and tool types provided only limited insights into the complex arrangements of multiple policy instruments commonly found in all policy fields (Jordan et al. 2011, 2012; Givoni 2013). However, they did provide detailed considerations as to the strengths and weaknesses, and pre-requisites, of many tools, which have greatly aided considerations of the design of policy mixes.

Moreover, while most older literature on policy tools focused on single instrument choices and fairly simple designs (Tupper and Doern 1981; Salamon 1989; Trebilcock and Prichard 1983), some early students of policymaking, like Dahl and Lindblom, Edelman, Lowi and others, had more flexible notions of the multiple means by which governments can give effect to policy and the reasons why different kinds of tools were effective. These helped inform modern design studies (Dahl and Lindblom 1953; Kirschen et al. 1964; Edelman 1964; Lowi 1966) and considerations of the effectiveness of policy mixes.

Mixes are combinations ...