![]() Part One Sustainable Urban Design Concepts

Part One Sustainable Urban Design Concepts![]()

1 Introduction

ADAM RITCHIE

Sustainability

Sustainability is about poetry, optimism and delight. Energy, CO2, water and wastes are secondary. The unquantifiable is at least as important as the quantifiable; according to Louis Kahn, ‘the measurable is only a servant of the unmeasurable’1 and ideally the two would be developed together. Using a term coined by the eighteenth-century author Jonathan Swift, this is a modest proposal.

This book identifies the major issues in making cities environmentally sustainable. By the time you are reading this sentence, we will, for the first time in history, have reached a milestone when more than half the world’s population, 3.3 billion people, are living in urban areas.2 Cities offer tremendous opportunities for community, employment, excitement and interest, which attract many of us. They can also create problems of congestion, noise and pollution which repel many others, or at least those who have the choice. These problems can be addressed, in part, through design, but success depends on recognising trade-offs and getting the balance right.

It is vital that we evolve towards sustainability in urban form, transport, landscape, buildings, energy supply, and all the other aspects of vibrant city living. Part of this will involve making cities more suitable for people, and therefore moving away from the previous policy of cities being for cars. Creating streets for pedestrians, cyclists and public transport is a key aspect of sustainable development.

Cities must also become greener for the sake of the diversity of many species (as well as humans) who inhabit them. Nature’s ecosystem, with its robust and stable systems, is one model for future cities. However, in addition to an ecosystem’s variety, diversity, redundancy and richness, we need poetry, whimsicalness, playfulness and excitement. Aristotle’s view was that a city should be designed to make its people secure and happy.3

This book is meant to inspire rather than be prescriptive. Ideas of planning, space and form are a backdrop to many of the points made, but our built environment suffers enough at present from people who were too sure of their solutions and those who thought in ‘silo’-based terms and over-planned and, thus, over-constrained development. Our contributors, however, believe that an integrated approach is needed. Density and the means of moving about the city are related. Landscape affects buildings. Noise influences the ventilation system selected and thus energy use. In turn, the energy use currently results in increased atmospheric pollution and CO2 emissions at power stations, which affect our health. Similarly, the built form affects access to sunlight and this influences both the energy use and our well-being. Cities are the very definition of a complex system and the preceding examples are only small strands of a tangled web of inter-connected causes and effects.

Some general themes run through the book. One is that appropriate solutions often depend on an understanding of the context: environmental, historical, social, etc. A second is that the appropriate scale for solutions is something larger than the individual building – it could be the block, the neighbourhood, the city, the region. Another is that solutions that require fewer resources are more likely to be robust. And so, for energy, the first step is to reduce demand and then examine how to meet it. In terms of movement in cities and towns, the robust solution is the dense walkable community, which does not have a high demand for either public or private transport. There is also a view that passive solutions are best. Things that move in the urban world tend to be less robust and require more maintenance. This is true whether one looks at cars, London Underground’s escalators, or pumps for heating systems.

The book is divided into two distinct parts. Part I provides an overview of the main issues affecting sustainable urban design, and discusses the tools and resources needed to tackle the subject. Part II features case study projects that demonstrate how these issues have been successfully negotiated by a range of expert practitioners. Our subject has essentially been cities in temperate climates that are neither bitterly cold in winter nor desperately hot and humid in summer. Our emphasis has been on new build, in part because that is where most of the contributors have had the best opportunity to develop new approaches. Improving the existing building stock is an even greater challenge, so, fortunately, a number of the ideas discussed in the book apply equally to upgrading existing buildings (see, for example, Chapter 18). Our case studies draw on some of the best experience from the UK, Europe and beyond, for example, Southwark in London (Chapter 11), Malmö in Sweden (Chapter 16) and Vancouver in Canada (Chapter 19). Many of these projects are brownfield sites where new buildings have often led to the regeneration of neighbourhoods. The increased densities that are likely to help us reduce CO2 emissions will depend in part on our ability to creatively recycle land, buildings and methods.

Reference is often made to the three interdependent aspects of sustainability: social, economic and environmental. This book will concentrate on the environmental. The emphasis on this aspect arises naturally – it is the field in which most of the contributors are working. A (readable) book is, of course, also necessarily limited in length and one needs to choose one’s focus. Sustainability is dependent on communities for its success, and developing the social dimension is often an arduous process. It could be said that the environment is the easiest aspect (in spite of the resistance to environmental improvement by some companies and governments), because it is much simpler to assess if, for example, CO2 emissions have been reduced rather than whether a scheme will successfully lead to economic regeneration. We also try to avoid the misconception that these three aspects can be equated simply to a ‘triple bottom line’ which is to trivialise sustainability somewhat by reducing it to a matter of simple economics. While there certainly is a price to pay for the transition to a sustainable future, see, for example, the review by Sir Nicholas Stern4 which evaluates the cost of action to reduce greenhouse gases, it misses less tangible but equally important aspects of sustainability, such as individuality.

Individuality creates space for the unexpected and the extraordinary as well as centring itself, in the best humanist tradition, on the person. If the social dominates the individual, everyone suffers from the deadening mediocrity that one finds outside the historic centres

1.1 De Montfort University, Queens Building, Leicester.

of cities as diverse as St Petersburg, Paris and London. This theme of uniqueness surfaces in urban design, landscaping and in individual buildings and will recur throughout the book. The exceptional towers of De Montfort University’s Queens Building (see Figure 1.1) are an example. The structures are symbolic of urban regeneration and yet also functional, serving as an integral part of the ventilation system.

Cities must have a rich set of interconnections or they will not be sustainable. For example, a city for walkers and cyclists needs more visual variety, more diversity, more ‘accidentals’ (in the musical sense) in its street patterns and its buildings, because the pace is slower and the mind both desires more and can take in more. We need to develop a rhythm in the city that will include places we can enjoy; this rhythm will be about moving – and stopping. This will help us return to cities designed for people, rather than for cars.

A city’s ‘accidents’ include such extraordinary views as this one down a narrow mews in London (see Figure 1.2), which combines dramatic changes of scale, buildings from different centuries, backs and fronts. One small image indicates the diversity and vitality of real cities. ‘Accidents’ are part of the normal pattern of our historical cities and appear to be anathema to many modern planners obsessed by regular patterns from an impossible aerial view. They are part of our past, our memory and thus a part of our poetry. They tell us that nothing was

1.2 View down a narrow street in central London.

1.3 Figure ground plan showing Malmö’s Western Harbour street pattern.

designed in an instant and so reinforce our sense of time. A delightful modern exception to conventional planning is the irregular streets of Malmö’s new Western Harbour, its grid described by principal architect Klas Tham as ‘distorted by the wind like a fishnet hung out to dry’5 (see Figure 1.3 and Chapter 16).

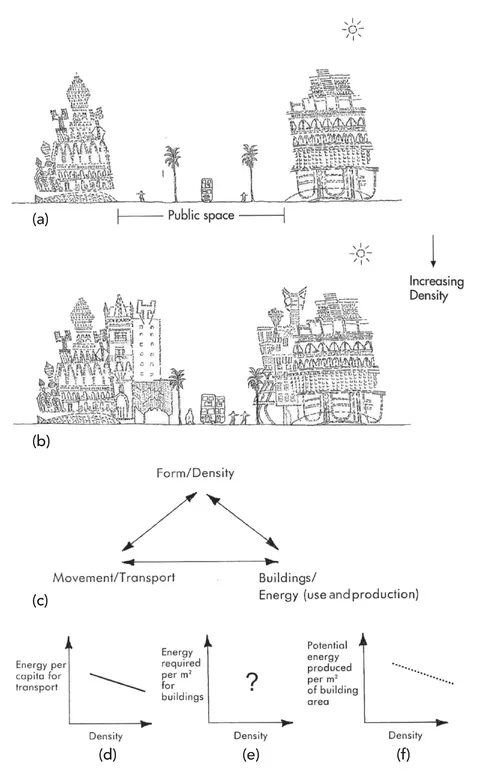

In many urban areas, public space, including parks and streets, constitutes more than half the total area of land. Buildings provide us with homes and workplaces and with commerce, industry and leisure. The space in between the buildings (see Figures 1.4a– 1.4b) provides vitality, light, amenity, room to travel and room to rest. Landscape is essential – plants soothe us and improve the microclimate. Our open space is home to wildlife, thus promoting biodiversity. It may incorporate vegetable gardens, and reed beds for waste treatment.

The interrelationship of three of the key factors in environmental sustainability can be viewed simplistically as a triangle (Figure 1.4c). One apex is form/density, a second is movement/transport and the third is buildings/energy (use and producti...