Chapter 1

The scope of leisure and recreation

Overview

I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who.

(Rudyard Kipling, ‘Just so Stories for Little Children’, 1902)

Kipling’s six honest serving men serve as the framework for introducing the subject. After exploring some difficulties in defining the scope of leisure and recreation, we settle on some pragmatic definitions to answer the question, ‘What?’. Leisure is more than just the disposable time available after work and other obligations, and the ‘non-productive consumption of time’ (Veblen 1899). It also reflects a state of mind, an optimal balance between the desires of an individual and the obligations felt to others. Each individual calibrates obligations on his, or her, own scale. Personal development and assertiveness training are just two of the techniques people are using to recalibrate their sense of obligation. Recreation is described as the activity (or lack of it) that people choose to engage in when at leisure, and it may be multifaceted, comprising physical, cognitive, emotional and social components. It may manifest itself as watching or taking part in sport, the arts, outdoor recreation, and a realm of other activities. Music and reading, as examples of recreation, are briefly explored. Management is described as arranging resources to achieve particular ends, in bio-physical and socio-economic environments.

Theories of motivation abound, and among them Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is helpful in exploring what it is that people are seeking from leisure and recreation. Behaviour is dependent on personality and environment (both biophysical and socioeconomic) and it is in these settings the manager can intervene. What distinguishes leisure from work is the freedom to choose, the activity, the place, the company, the intensity of physical, mental and emotional effort that is deployed. The end may be happiness, a search for meaning, or the journey itself. This is a matter for the participant. What we choose to do depends in part on the life stage we are involved in, as an individual, whether independent, dependent youngster, or with young or old dependants. Similarly, the amount of time we have available will reveal different opportunities. Our desires and the opportunities afforded will often have a relationship with natural periodicities or cycles, whether during the day, lunar month or year, even though technologically we can have a twenty-four-hour day.

Recreation is often a blend of physical, mental and emotional activity, most often enjoyed in company. We can study at different scales of resolution, and at each, we should be able to identify five stages: anticipation, journey, event, journey back, and recall (Clawson and Knetsch 1971). We can study an event during the day, the day itself, the holiday or the life of the participant. Each event will have a beginning, a middle and an end. Play is important in communicating and in preparing ourselves for life.

Home, school and the workplace will claim a large part of our leisure time. Other settings are important too: the spaces within our neighbourhood—outside, and inside public buildings, important neutral spaces. Travelling provides a setting too, with a moving backcloth, and holidays provide opportunities for extended contact with the family, or other referent group. We tend to share recreational experiences with others, even when in pursuit of wilderness experiences; first with family, then playmates, colleagues from work and fellow club members. The distribution of opportunities for recreation and leisure is not, though, equitable. Typically, and certainly in Britain, women, children, older people, people with disabilities and ethnic minorities tend to have fewer opportunities (Bramham et al. 1989).

How we approach leisure will depend on numerous influences. Genetic makeup, personality, the influence of the family, teachers and peer group will all play a part. Science and the manager’s analytical and creative thinking will help to address the issues, which are awaiting intervention. Among the prominent issues are: balancing obligations with leisure, travel, the motor car, sustainable development and management of leisure, equity, the roles of the state, private and voluntary sectors, and the role of management. Managers need to determine where to intervene to best effect, towards useful policies and programmes and in areas where the intervention will make a real difference.

What?

We could define ‘leisure’ simply as the time available that we can spend as we choose. Simple though this definition is, we immediately find a complication. In its purest state, it is probably as difficult to find as the Holy Grail. The problem is that each of us feels very differently about our obligations, whether to our colleagues at study or at work, our families, our friends, our communities or to society at large. How we feel will be the product of many influences and many of these will be specific to our own culture. The time we are describing here is the time left, after taking away the hours we spend on:

- work;

- study (for pupils and students only);

- sleep;

- caring for dependants;

- housework.

Many use the term ‘leisure’ to describe the time we have left after we have carried out essential functions, but that is unhelpful. This book will develop the argument that leisure itself is an essential component of our lives, and not a residual.

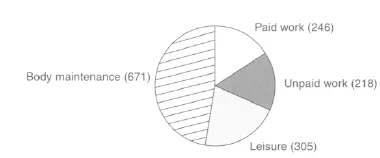

FIGURE 1.1 Work or leisure? Proportions of the day (minutes)

Source: Gershuny and Fisher (1999)

There are many alternative views, and the reader in search of definitions will not be disappointed (Dumazedier 1967; Godbey 1994; Goodale and Godbey 1988; Glyptis 1993; Haworth 1997; Kelly 1993; Neulinger 1974; Parker 1976; Rapoport and Rapoport 1975; Roberts 1978; Seabrook 1989). It has been said that in the past the focus of study has been on the impacts of leisure and recreation on the physical environment rather than on the socio-economic environment (Dower and Downing 1975). Some consider leisure as a state of mind, an approach to life, a part of our lives set aside from other obligations. Often the terms ‘leisure’ and ‘recreation’ are used interchangeably, but not in this book. Here the term ‘recreation’ is reserved to describe what we do with, or at, our ‘leisure’. It is the chosen activity (or lack of activity) in which we take part, when we have the choice as to how to spend our remaining or disposable time.

Think for a few moments about the recreations you enjoy. Chances are that they will include different kinds of activity, from which you may choose according to the time of day or year, the time available, the money available, your mood and the preferences of others close to you. If you made a list, physical activity and exercise are sure to be there. The list would include more cerebral activity as well (even emotional or spiritual activity), and would often include activities you did not ordinarily, or otherwise, do. There will be times when you choose rather less intense activity and wish to be reflective or just reactive.

You might wish to exercise your senses, be concerned with a more passive role, or have a desire to consume goods, services and (famously) food and drink. Or you might want to listen to music. Commentators have found that there is a reasonable consistency across people, about what activities they engage in, which is neatly explained by the core plus balance model, described by Kelly (1999:143–4). The core consists of activities that are easily accessible, and therefore also low-cost. Typically this core can be engaged in around the house, or neighbourhood, and among the daily pattern of events. It may include: reading, walking, listening to the radio, watching television, chatting with friends and family informally, conversation generally and engaging in sexual activity. The balance of leisure is more likely to be planned, and could change or develop during the life course. Managers are more usually focused on this area, the balance. To be effective managers we should consider how our interventions will help facilitate (or at least not impede) core leisure too, by providing and maintaining appropriate settings.

TABLE 1.1 Favourite recreational activities for periods of up to five minutes

As well as enjoying watching others, listening or otherwise consuming, recreation can also take the form of creative, expressive or productive activity. We all have a need to turn our innermost thoughts into some more tangible form which we can share with others, in the hope that they too will share something of what we felt when we first had that idea, or perhaps to provoke thought and a different reaction. For whatever reason, some of us spend a good proportion of our lives engaged in such activity that spans the complete range of arts and crafts. There is nothing more enchanting than to receive a gift, whether sketch, piece of pottery, poem or even letter, created or crafted by someone close to you.

Sport is more than simple physical activity (Cashmore 1990). Usually each sport has a set of rules that ensure fair play and encourage full enjoyment and development of potential within some convenient boundary. Sport may involve competition, co-operation, risk, physical exertion, stamina, concentration, hand-eye motor co-ordination of self, co-ordination, rhythm and timing across a whole team and crucially, fun. Some sports encourage cardiovascular activity, which among those in an increasingly sedentary technological world is a welcome break, from driving a desk or computer, or an escape (Segrave 2000). Physical activity of this kind releases endorphins, chemical messengers (hormones) that increase our sense of pleasure (Greenfield 1997).

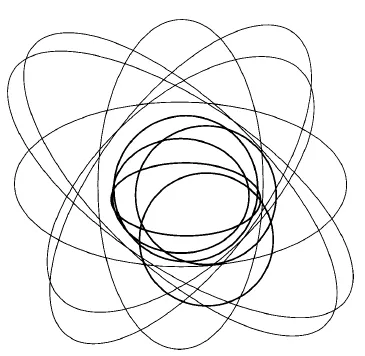

FIGURE 1.2 Core plus balance. For simplicity, each individual’s interests are represented by two ellipses. The first, inner, ellipse describes core activities and interests, such as conversation, reading, listening to the radio—generally easily accessible, and no great effort is required. The second, outer, ellipse describes the personal blend of activities and interests that provides the balance, often requiring greater planning or effort. The opportunities for management intervention are quite different in each case but focus on managing settings, physical and social

The arts encompass every conceivable branch of practical activity guided by a set of principles (Chambers 1972): visual arts like drawing and painting; literary arts like poetry and prose; music; performing arts like drama, dance, ballet, song and opera; plastic arts like sculpture and modelling; radio, television, film and video.

More practical skills include the further application of the arts, such as through carpentry and metalwork, decorating the inside of our houses. For some, activities such as car maintenance are recreational and an enormous industry has built up in some cultures supplying every gadget and material which you could imagine useful (and some rather less so) in the pursuit of Do-It-Yourself. Most of us also spend some time decorating or managing the spaces outside our houses, our gardens, becoming immersed in the earth and feeling some connection with the real world.

BOX 1.1 ‘Music, the greatest good that mortals know’

(Joseph Addison, 1672–1719; from Cohen and Cohen 1960:1)

One of the most ubiquitous art forms enjoyed by all ages and cultures is music. It starts with the heartbeat. People have been aware of the restorative and mood-changing effects of music for thousands of years (Plato, in Abraham 1979). It can be used to put people into the right frame of mind (or mood) for a particular purpose (Argyle 1996:203–5), for social activity, for relaxation, for expressing emotions (Csikszentmihalyi 1992). It can be used to marshal courage when troops are going into battle, or to galvanise football fans into a single crowd. Musicians and composers are well aware of the characteristics of music that can cause different effects (Meyer 1956).

There are descriptions from biblical times of the effects of trumpets, cymbals and other instruments. Rameau wrote his Traité de l’harmonie in 1722 (Rameau 1971) describing the effects of different treatments, cadences and fugue, with an indication of the resultant effects. Recently P.Robertson (leader of the Medici String Quartet), the psychiatrist and writer A.Storr and colleagues have set up the Music Research Institute (www.mri.ac.uk) to advance ‘appreciation of the beneficial role that music can play in the enhancement of human experience’. Some of the work in which they have been involved has demonstrated the scientific basis of what many music lovers intuitively know. Music can make us feel very good indeed. Using magnetic resonance imaging, it is possible to plot and record brain activity responding to music. This brain activity releases chemical neurotransmitters, which in turn, depending on the type of transmitter, makes us feel different types of ‘good’. Scientific evidence is required to persuade people of the value of music, as many Western societies are spending less time and money on music education as they try to squeeze ever more ‘important’ subjects into the curriculum.

For some people, music is essential to life. A survey (reported in Storr 1997:123) revealed that most of us spend at least one or two hours producing music each day, quite apart from the time spent in listening. We should not be surprised that music can be so potent in therapy, in treating autistic children and children traumatised by war, and in pain reduction. The different moods and effects which can be induced are so wide-ranging that song writers and musicians will never run out of surprises, harmonies and melodies with which to please us, whether pop or classical, rap or jazz.

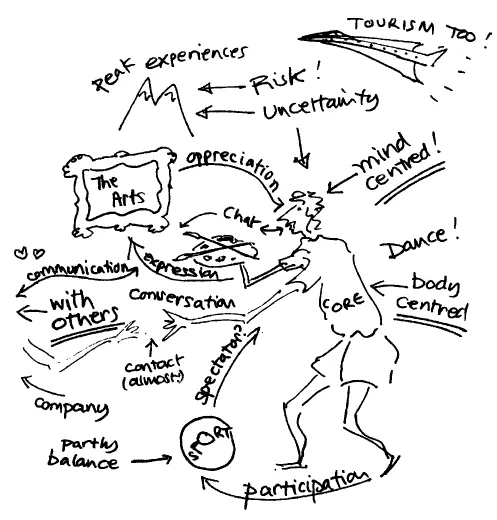

FIGURE 1.3 Different kinds of recreation: mind-centred, body-centred and with others

Another group of recreations takes us outside our immediate home setting, where we are more concerned with contact with the elements and the natural and physical world. Experiences such as these, whether through white water canoeing, sailing across oceans, walking among the mountains or along coast, watching birds or other animal and plant life, provide people with opportunities to marvel at the natural world. Inevitably, the more we marvel the more the experience becomes an emotional and often spiritual one, as we feel more a part of the complex world around us. These experiences can be passed on with eloquence, using the written word (Shackleton 1999; Simpson 1997; Slocum 1949).

Enough of recreation and leisure; what is management? In this book, ‘management’ is used to describe the activities of managers, directing and arranging resources to achieve particular ends. A manager is anyone engaged in that activity. The book describes some of the processes which managers can use in respect of the environments in which we enjoy our leisure and recreation. The classical factors of production—land, labour, and capital—represent one simple classification of those we have available. Another approach is to view our world as a number of interacting processes. If we understand these processes we can begin to work with them, to direct and arrange resources to shape and develop the environments we want, as landscape ecologists do (Diaz and Apostol 1993). In this model, it becomes important to understand the existing dynamic background. When managing impacts on the physical environment, we should recognise that there are many natural cycles and processes operating, which we need to take into account. In just the same way, when we intervene in the socio-economic environment, we need to recognise the other political, economic and social processes at work. We need to recognise the differences between those we have to work with, and those we can barely shape.

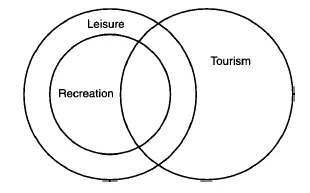

We choose the environments in which we spend our leisure. Our urge to explore our environment, and seek out new worlds, new settings and new people, is given almost totally free rein through tourism. Much of tourism is very closely related to leisure and recreation. Mieczkowski’s elegant conceptualisation (Figure 1.4) is useful when considering the scope of interest.

The freedom to choose the place where we enjoy our own time is fundamental. In olden times we might have been constrained by choosing between environments or settings that existed; within the woodland, open savannah, beside the river or at the coast. For some thousands of years, man has been shaping the environment, inside and outside, and we have a sophisticated understanding of what effects different treatments may generate.

Just as we choose the physical setting, so too do we choose with whom we spend our time. This is a fundamental freedom associated with leisure and recreation. We intuitively manage the social and economic settings within which we operate. The social setting is just as important in determining the outcomes for leisure as the biophysical environment. The person I choose to play squash with may not be the same person I would choose to accompany to a concert.

FIGURE 1.4 Leisure, recreation and tourism: Mieczkowski’s conceptualisation

Source: Mieczkowski (1981)

BOX 1.2 Reading and writing for pleasure

If you have ever tried your hand at writing with a quill pen, you will be able to imagine the hours it would take to write a book by hand. The Venerable Bede, working in the north of England, completed his Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum in 731, by when (aged 58) he had written nearly forty books (Harvey 1967:75). Spare a thought, then, for the dutiful monks setting down on paper, or vellum, stories which would be seen by only a handful of people each month or year...